East African Researcher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi Le

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a Acknowledgment On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Mr. Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Gomba District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment for Gomba District was a combination of spatial modeling using adaptive, sensitivity and exposure spatial layers and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

Stichting Porticus

CATHOLIC SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAMME FOR UGANDA C/o University of Kisubi P.O. Box 182 Entebbe, Uganda Photograph Tel. +256 777 606093 Email: [email protected] APPLICATION FORM Please be advised that the eligibility requirements for the Scholarship Programme have changed in 2019; please refer to the Catholic Scholarship Programme Eligibility Requirements, 2019 which are attached as Annex A. Each applicant must write a Personal Statement, please follow the template attached as Annex B. Each applicant must have two (2) Letters of Recommendation, including one from your superior. Please follow the template attached as Annex C. Finally, this application should be submitted together with the list of documents on page 4. PERSONAL DETAILS Surname:…………………………………………………… First and Middle names: …….……………………….……………………. Other names ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…………..………..……… Date of birth: ………………………………...... Place of birth: …………………………………..…………….................... Nationality: ………………………………………. Identity card no/ Passport no:…….…..………………………...……… Religious ☐ Lay ☐ Mobile phone numbers: ………………….…………….…................. E-mail: ……………………………………………………………………………………………. Gender: ……….……………………..……………. Permanent address: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……...……….. Name of Nominating Institution (the Congregation or organization that is nominating the student for a scholarship): ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………….……. Local Congregation:………………………………………. Pontifical Institute……………………………………………..………………. Superior/Next -

THE REPUBLIC of UGANDA in the CHIEF MAGISTRATES COURT of ENTEBBE at ENTEBBE CRIMINAL REGISTRY CAUSELIST for the SITTINGS of : 31-08-2020 to 04-09-2020

8/31/2020 Court Case Administration System THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE CHIEF MAGISTRATES COURT OF ENTEBBE AT ENTEBBE CRIMINAL REGISTRY CAUSELIST FOR THE SITTINGS OF : 31-08-2020 to 04-09-2020 MONDAY, 31-AUG- 2020 CHIEF MAGISTRATE BEFORE:: ALUM AGNES Case Case Nature of Time Pares Charge CRB No Sing Type number Category Appl./Appeal UGANDA VS ENT-00-CR- ASP Hearing - Criminal ATTEMPTED Kajjansi/CRB 1. 09:00 CO-0506- AMUTUHAIRE prosecuon Offence ROBBERY 762/2019 2019 BRIGHT & case ANOR ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS Hearing - Criminal ATTEMPT TO Entebbe Police 2. 09:00 CO-0306- AGABA prosecuon Offence MURDER Staon/CRB 491/2020 2020 ROBERT case UGANDA VS ENT-00-CR- Hearing - Criminal MASABA 3. 09:00 CO-0089- Kisubi/197/2019 prosecuon Offence GEORGE 2020 case WILLIS ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS UTTERING Hearing - Criminal Aviaon Security 4. 09:00 CO-0573- BIZIMANA FALSE prosecuon Offence Police/CRB:184/2019 2019 ERIC DOCUMENTS case ENT-00-CR- UGANDAQ VS Hearing - Criminal Entebbe Police 5. 09:00 CO-0323- KAMANYA prosecuon Offence Staon/545/2020 2020 MIKE case MAGISTRATE GRADE I BEFORE:: BIRUNGI PHIONAH Case Case Nature of Time Pares Charge CRB No Sing Type number Category Appl./Appeal ENT-00-CR- Entebbe Police Criminal UGANDA VS CRIMINAL 1. 09:00 CO-0678- Staon/CRB Ruling Offence KIRUME JOHN TRESSPASS 2018 1043/2017 ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS Criminal Hearing 2. 09:00 CO-0398- BUKOMEKO Kasanje/21/2019 Offence (unspecified) 2019 MIKE ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS Hearing - Criminal Entebbe Police 3. 09:00 CO-0060- NAKAKAWA THEFT prosecuon Offence Staon/1380/2019 2020 REMMY case UGANDA VS ENT-00-CR- Hearing - Criminal NAMUNYO 4. -

Parenting Styles and Students' Academic Performance

PARENTING STYLES AND STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF SENIOR TWO AND SENIOR FIVE STUDENTS IN MASULIITA TOWN COUNCIL: A CASE OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS BY KYOBE CHARLES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION HUMANITIES AND SCIENCES OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF A MASTER’S DEGREE EDUCATION MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING OF NKUMBA UNIVERSITY OCTOBER, 2018 1 DECLARATION I, Kyobe Charles, hereby declare that this research report is my original work and to the best of my knowledge, it has never been submitted for any academic award in this or any other institution of higher learning. i APPROVAL This dissertation titled “PARENTING STYLES AND STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF SENIOR TWO AND SENIOR FIVE STUDENTS IN MASULIITA TOWN COUNCIL: A CASE OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS” has been prepared by Kyobe Charles under my supervision and it is now ready for submission. ii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my loving and caring family for the sacrifices made in supporting my studies. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank the Almighty God who has brought me this far in my life, and has kept me safe to this stage. I pray that he can give me more countless years so that I can serve him relentless. I wish to thank my Superior General the Archbishop of Kampala Archdiocese Dr. Cyprian Kizito Lwanga, the Vicar General Monsignor Charles Kasibante and my Rector Reverend Father Ceasar Matovu, and my spiritual director Reverend Father Emmanuel Kasajja for all the support you have accorded throughout my academic endavours to this stage. To my dear parents; Mr. -

2018 ANNUAL MEETING from Imitation to Innovation

2018 ANNUAL MEETING From Imitation to Innovation NOVEMBER 10 – 12, 2018 DOHA, QATAR HOSTED BY INDEX WELCOME ………………………………………………………………………… 3 AGENDA …………………………………………………………………………... 4 GROUP BREAKOUTS …………………………………………………………… 10 GOVERNING BOARD …………………………………………………………… 13 DOCTRINAL STUDY GROUPS ………………………………………………… 14 UNIVERSITIES ATTENDING …………………………………………………… 15 BOARD OF GOVERNORS ATTENDEES ……………………………………... 17 QATAR UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF LAW ATTENDEES …………………. 21 JUDICIAL ATTENDEES …………………………………………………………. 25 ATTENDEES ……………………………………………………………………… 29 SECRETARIAT …………………………………………………………………… 58 SINGAPORE DECLARATION ………………………………………………….. 59 MADRID PROTOCOL ……………………………………………………………. 61 JUDICIAL STANDARDS OF A LEGAL EDUCATION ……………………….. 62 SELF-ASSESSMENT REPORT ………………………………………………… 63 EVALUATION, ASSISTANCE, AND CERTIFICATION PROGRAM ……….. 66 2 WELCOME On behalf of all the members of the International Association of Law Schools Board of Governors, we want to welcome each and every one of you to our 2018 Annual Meeting. This is our eleventh annual meeting where over 115 law teachers from more than 30 countries have gathered together to discuss and formulate new strategies to improve legal education globally. Almost half of our participants are senior law school leaders (deans, vice deans and associate deans). We warmly welcome all the familiar faces from these many years – welcome and thank you for your continued engagement in advancing the cause of improving legal education globally. For those who are new, a special warm welcome from our community. Please meet your colleagues from around the world. We look forward to working with you in this challenging and engaging effort. The IALS is a non-political, non-profit learned society of more than 160 law schools and departments from over 55 countries representing more than 7,500 law faculty members. One of our primary missions is the improvement of law schools and conditions of legal education throughout the world by learning from each other. -

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda At The Annual Budget Conference - Financial Year 2016/17 For Ministers, Ministers of State, Head of Public Agencies and Representatives of Local Governments November11, 2015 - UICC Serena 1 H.E. Vice President Edward Ssekandi, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda, I was informed that there is a Budgeting Conference going on in Kampala. My campaign schedule does not permit me to attend that conference. I will, instead, put my views on paper regarding the next cycle of budgeting. As you know, I always emphasize prioritization in budgeting. Since 2006, when the Statistics House Conference by the Cabinet and the NRM Caucus agreed on prioritization, you have seen the impact. Using the Uganda Government money, since 2006, we have either partially or wholly funded the reconstruction, rehabilitation of the following roads: Matugga-Semuto-Kapeeka (41kms); Gayaza-Zirobwe (30km); Kabale-Kisoro-Bunagana/Kyanika (101 km); Fort Portal- Bundibugyo-Lamia (103km); Busega-Mityana (57km); Kampala –Kalerwe (1.5km); Kalerwe-Gayaza (13km); Bugiri- Malaba/Busia (82km); Kampala-Masaka-Mbarara (416km); Mbarara-Ntungamo-Katuna (124km); Gulu-Atiak (74km); Hoima-Kaiso-Tonya (92km); Jinja-Mukono (52km); Jinja- Kamuli (58km); Kawempe-Kafu (166km); Mbarara-Kikagati- Murongo Bridge (74km); Nyakahita-Kazo-Ibanda-Kamwenge (143km); Tororo-Mbale-Soroti (152km); Vurra-Arua-Koboko- Oraba (92km). 2 We are also, either planning or are in the process of constructing, re-constructing or rehabilitating -

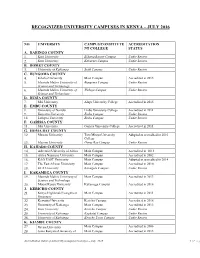

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

S5 Cut Off May Raise

SATURDAY VISION 10 February 1, 2020 UCE Vision ranking explained Senior Five cut-off points (2019) SCHOOL Boys SCHOOL Boys BY VISION REPORTER their students in division one. Girls Fees (Sh) Girls Fees (Sh) The other, but with a low number of St. Mary’s SS Kitende 10 12 1,200,000 Kinyasano Girls HS 49 520,000 The Saturday Vision ranking considered candidates and removed from the ranking Uganda Martyrs’ SS Namugongo 10 12 1,130,000 St. Bridget Girls High Sch 50 620,000 the average aggregate score to rank was Lubiri Secondary School, Annex. It Kings’ Coll. Budo 10 12 1,200,000 St Mary’s Girls SS Madera Soroti 50 595,200 the schools. Saturday Vision also also had 100% of its candidates passing Light Academy SS 12 1,200,000 Soroti SS 41 53 UPOLET eliminated all schools which had in division one. Namilyango Coll. 14 1,160,000 Nsambya SS 42 42 750,000 the number of candidates below 20 There are other 20 schools, in the entire London Coll. of St. Lawrence 14 16 1,300,000 Gulu Central HS 42 51 724,000 students in the national ranking. nation, which got 90% of their students in The Academy of St. Lawrence 14 16 650,000 Vurra Secondary School 42 52 275,000 A total of about 190 schools were division one. removed from the ranking on this Naalya Sec Sch, Namugongo 15 15 1,000,000 Lango Coll. 42 500,000 basis. nTRADITIONAL, PRIVATE Seeta High (Green Campus) 15 15 1,200,000 Mpanga SS-Kabarole 43 51 UPOLET This is because there were schools with SCHOOLS TOP DISTRICT RANKING Seeta High (Mbalala) 15 15 1,200,000 Gulu SS 43 53 221,000 smaller sizes, as small as five candidates, Traditional schools and usual private top Seeta High (Mukono) 15 15 1,200,000 Lango Coll., S.S 43 like Namusiisi High School in Kaliro. -

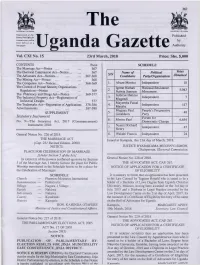

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [2 3 Rd M a R C H

The THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA iTHE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette Authority Vol. CXI No. 15 23rd March, 2018 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTENTS Pa g e SCHEDULE The Marriage Act—Notice ................ ... 367 The Electoral Commission Act—Notice............... 367 Name o f Political Votes S/N The Advocates Act—Notices... ... ... 367-368 Candidates Party/Organisation Obtained The Mining Act—Notice ................ ... 368 The Companies Act—Notices................ ... 368-369 1. Abuze Monica Independent 18 The Control of Private Security Organisations Igeme Nathan National Resistance 2. 5,043 Regulations—Notice ... ... ... 369 Nabeta Samson Movement The Pharmacy and Drugs Act—Notice ... 369-377 Isabirye Hatimu 3. Independent 7 The Industrial Property Act—Registration of Mugendi Industrial Designs ... ... ... 377 Mayemba Faisal The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 378-386 4. Independent 117 Masaba Advertisements ... ... ... ... 387-398 Mugaya Paul People’s Progressive 5. 48 SUPPLEMENT Geraldson Party Statutory Instrument / Forum for 6. Mwiru Paul 6,654 No. 9—The Insurance Act, 2017 (Commencement) Democratic Change Instrument, 2018. Nyanzi Richard 7. Independent 47 Henry General Notice No. 226 of 2018. 8. Wakabi Francis Independent 24 THE MARRIAGE ACT Issued at Kampala, this 21st day of March, 2018. [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] NOTICE. JUSTICE BYABAKAMA MUGENYI SIMON, Chairperson, Electoral Commission. PLACE FOR CELEBRATION OF MARRIAGE [Under Section 5 o f the Act] General Notice No. 228 of 2018. In e x e r c is e of the powers conferred upon me by Section 5 of the Marriage Act, I hereby licence the place for Public THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. -

E464 Volume I1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM

E464 Volume i1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM Public Disclosure Authorized Preparedfor: UGANDA A3 NILE its POWER Richmond;UK Public Disclosure Authorized Fw~~~~I \ If~t;o ,.-, I~~~~~~~ jt .4 ,. 't' . .~ Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: t~ IN),I "%4fr - - tt ?/^ ^ ,s ENVIRONMENTAL 111teinlauloln.al IMPACT i-S(. Illf STATEME- , '. vi (aietlph,t:an,.daw,,, -\S_,,y '\ /., 'cf - , X £/XL March, 2001 - - ' Public Disclosure Authorized _, ,;' m.. .'ILE COPY I U Technical Resettlement Technical Resettlement Appendices and A e i ActionPlan ,Community ApenicsAcinPla Dlevelopment (A' Action Plan (RCDAP') The compilete Bujagali Project EIA consists of 7 documents Note: Thetransmission system documentation is,for the most part, the same as fhat submittedto ihe Ugandcn National EnvironmentalManagement Authority(NEMAI in December 2000. Detailsof the changes made to the documentation betwoon Dccomber 2000 and the presentsubmission aro avoiloblo from AESN P. Only the graphics that have been changed since December, 2000 hove new dates. FILE: DOChUME[NTC ,ART.CD I 3 fOOt'ypnIp, .asod 1!A/SJV L6'.'''''' '' '.' epurf Ut tUISWXS XillJupllD 2UI1SIXg Itb L6 ... NOJIDSaS1J I2EIof (INY SISAlVNV S2IAIlVNTIuaJ bV _ b6.sanl1A Puu O...tp.s.. ZA .6san1r^A pue SD)flSUIa1DJltJJ WemlrnIn S- (7)6. .. .--D)qqnd llH S bf 68 ..............................................................--- - -- io ---QAu ( laimpod u2Vl b,-£ 6L ...................................... -SWulaue lu;DwIa:43Spuel QSI-PUU'l Z btl' 6L .............................................----- * -* -SaULepunog QAfjP.4SlUTtUPad l SL. sUOItllpuo ltUiOUOZg-OioOS V£ ££.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~A2~~~~~~~~~3V s z')J -4IOfJIrN 'Et (OAIOsOa.. Isoa0 joJxxNsU uAWom osILr) 2AX)SO> IsaIo4 TO•LWN ZU£N 9s ... suotll puoD [eOT20olla E SS '' ''''''''..........''...''................................. slotNluolqur wZ S5 ' '' '' '' ' '' '' '' - - - -- -........................- puiN Z'Z'£ j7i.. .U.13 1uu7EF ................... -

Funded Degree Programmes and Partners Involved in Sub-Sahara Africa (2020/21)

Funded degree programmes and partners involved in Sub-Sahara Africa (2020/21) Regional universities/networks are participating in the scholarship programme as partner institutions Call for application West and Central Africa: Deadline: February, 10th 2021 West and Central Africa Benin • University of Abomey – Calavi (UAC) Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, Mathematics (Master, PhD) International Chair in Mathematical Physics and Applications (CIPMA), Natural Sciences (Master, PhD) Burkina Faso • International Institute for Water and Environmental Engineering (2iE), Engineering (Master, PhD) Ghana • University for Development Studies (UDS), Department of Public Health, Medicine - Public Health (Master Phil, Master Sc) • University of Ghana, Regional Institute for Population Studies (RIPS), Humanities / Political Science (Master, PhD) West African Center for Crop Improvement (WACCI), University of Ghana, Agricultural Sciences (Master, PhD) Nigeria • University of Ibadan, Subject fields: Fisheries Management and Energy Studies (Master) Network • Centre d 'Etudes Régional pour l'Amélioration de l'Adaptation à la Sécheresse (CERAAS), Agricultural Sciences (Master, PhD) Eastern Africa Call for application Eastern Africa: Deadline: December, 15th 2020 Ethiopia Addis Ababa University - IPSS, Subject field: Global & Area Studies (PhD) • Hawassa University - Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources (WGCF), Agro-Forestry (Master) Kenya • Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT), Information Technology (PhD), Mechanical -

Arising from Chief Magistrate Court of Nsangiat Mpigi Divorce Cause No

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA AT MPIGI CIVIL REVISION NO.004 of 2018 (Arising from Chief Magistrate Court of Nsangiat Mpigi Divorce Cause No. 2/2017) HAJJI KASOZ ABDALLAH:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::APPLICANT VERSUS NALWOGA NAKATO:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::RESPONDENT BEFORE: HON. JUSTICE OYUKO ANTHONY OJOK 10 RULING Background This is an application brought under S. 83 and S.98 of the Civil Procedure Act, O.52r1-3 of the Civil Procedure Rules. The application seeks for orders that the decision by the trial Magistrate Her Worship SarahBasemera Anne (Mpigi) be revised and set-aside. The grounds of the application are set out in the Notice of Motion supported by an affidavit of KasoziAbdallah of M/s MuslimCentre for Justice and law Basiima Building, Plot 401/3 Bombo Road, P.O BOX 6929, Kampala. 20 Thegrounds are as follows: 1. That I got married with the Respondent in 1980 under the Provisions of the marriage and divorce of Mohammedans Act Cap (Marriage Certificate hereto attached and marked A). 1 | P a g e 2. That I developed irreconcilable differences with the Respondent and hence opted to Divorce. 3. That I instituted divorce proceedings in the Sharia Court at Uganda Muslim supreme Council which were attended by the Respondent and Judgment was duly delivered (Judgment and proceedings hereto attached and marked B). 4. That the Respondent instituted Divorce Cause No. 002 of 2017 in the Chief Magistrate’s Court of Wakiso at Nsangi. 5. That the Learned Magistrate while applying the Divorce Act Cap 249 held that the matrimonial property be divided between me and the Respondent equally, 10 (Judgment and record of proceedings hereto attached and marked C and D respectively).