The Relationship Between Bite Force, Morphology, and Diet in Southern African Agamids W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nyika and Vwaza Reptiles & Amphibians Checklist

LIST OF REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS OF NYIKA NATIONAL PARK AND VWAZA MARSH WILDLIFE RESERVE This checklist of all reptile and amphibian species recorded from the Nyika National Park and immediate surrounds (both in Malawi and Zambia) and from the Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve was compiled by Dr Donald Broadley of the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, in November 2013. It is arranged in zoological order by scientific name; common names are given in brackets. The notes indicate where are the records are from. Endemic species (that is species only known from this area) are indicated by an E before the scientific name. Further details of names and the sources of the records are available on request from the Nyika Vwaza Trust Secretariat. REPTILES TORTOISES & TERRAPINS Family Pelomedusidae Pelusios rhodesianus (Variable Hinged Terrapin) Vwaza LIZARDS Family Agamidae Acanthocercus branchi (Branch's Tree Agama) Nyika Agama kirkii kirkii (Kirk's Rock Agama) Vwaza Agama armata (Eastern Spiny Agama) Nyika Family Chamaeleonidae Rhampholeon nchisiensis (Nchisi Pygmy Chameleon) Nyika Chamaeleo dilepis (Common Flap-necked Chameleon) Nyika(Nchenachena), Vwaza Trioceros goetzei nyikae (Nyika Whistling Chameleon) Nyika(Nchenachena) Trioceros incornutus (Ukinga Hornless Chameleon) Nyika Family Gekkonidae Lygodactylus angularis (Angle-throated Dwarf Gecko) Nyika Lygodactylus capensis (Cape Dwarf Gecko) Nyika(Nchenachena), Vwaza Hemidactylus mabouia (Tropical House Gecko) Nyika Family Scincidae Trachylepis varia (Variable Skink) Nyika, -

Morphology, Locomotor Performance and Habitat Use In

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2020, XX, 1–12. With 4 figures. Morphology, locomotor performance and habitat use in Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/biolinnean/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/biolinnean/blaa024/5802286 by guest on 15 March 2020 southern African agamids W. C. TAN1,2,3,*, , B. VANHOOYDONCK4, J. MEASEY3, and A. HERREL1,4, 1UMR 7179 C.N.R.S/M.N.H.N., Département Adaptations du Vivant, 55 rue Buffon, 75005, Paris Cedex 5, France 2Université de Poitiers – UFR Sciences Fondamentales et Appliquées, Laboratoire EBI Ecologie & Biologie des Interactions, UMR CNRS 7267, Poitiers, France 3Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany & Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa 4Department of Biology, University of Antwerp, Universiteitsplein 1, B-2610 Antwerpen, Belgium Received 11 December 2019; revised 10 February 2020; accepted for publication 10 February 2020 Understanding the relationships between form and function can help us to understand the evolution of phenotypic diversity in different ecological contexts. Locomotor traits are ecologically relevant as they reflect the ability of an organism to escape from predators, to catch prey or to defend territories. As such, locomotion provides a good model to investigate how environmental constraints may influence an organism’s performance. Here, we investigate the ecomorphological relationships between limb morphology, locomotor performance (sprint speed and endurance) and habitat use in six southern African agamid species. The investigated agamid species showed differences in hind limb and toe lengths. Both of these traits were further correlated with endurance capacity. This association was supported by stepwise multiple regression analyses. -

A Second Record of Scolecomorphus Kirkii Boulenger, 1883 (Gymnophiona: Scolecomorphidae) for Mozambique

Herpetology Notes, volume 8: 59-62 (2015) (published online on 10 March 2015) A second record of Scolecomorphus kirkii Boulenger, 1883 (Gymnophiona: Scolecomorphidae) for Mozambique Harith Omar Morgadinho Farooq1 and Werner Conradie2,* The herpetofauna of northern Mozambique (Nampula, Branch et al., 2014), crustaceans (Daniels and Bayliss, Niassa, and Cabo Degabo Provinces) remains one of the 2012) and bats (Taylor et al., 2012). While Portik et al. most poorly-known in Africa. This is a consequence of (2013a) summarised the herpetofauna of the inselbergs the physical inaccessibility of the region as well as the of northern Mozambique, they overlooked the valuable protracted civil war, which affected the study of many amphibian collections in the technical report by Branch areas. Mozambique is expected to have a large diversity (2004) from Niassa Game Reserve and the herpetofaunal of herpetofauna due to the variety of different habitat collections from Mount Mabu (Timberlake et al., 2012), types available and the large size (area) of the country. which led to underestimation and incorrect accounts of The lack of scientific studies of northern Mozambique the herpetofaunal diversity of the montane inselbergs of has led to widely disparate and inaccurate summaries northern Mozambique. of the herpetofaunal diversity of the country. While In November 2011 and May 2014 a team of scientists, there are no formal publications that explicitly deal mountain climbers, and conservationists had the with this topic, reputable internet sources indicate that opportunity to survey Mount Namuli, which resulted 221 reptile (Uetz, 2015) and 69 amphibian species in some additions to the herpetofauna of that area. (AmphibiaWeb, 2015) are expected to occur in the whole of Mozambique. -

The Amphibians and Reptiles of Kakamega Forest, Western Kenya

07_Wagner&Böhme-2.qxd 12.08.2007 14:01 Uhr Seite 123 Bonner zoologische Beiträge Band 55 (2006) Heft 2 Seiten 123–150 Bonn, Juli 2007 Herpetofauna Kakamegensis – The amphibians and reptiles of Kakamega Forest, western Kenya Philipp WAGNER & Wolfgang BÖHME Bonn, Germany Abstract. We present an annotated checklist of the herpetofauna of Kakamega Forest with comments on the biology and systematics of the taxa. Twenty-five amphibian, one turtle, 22 lizard and 36 snake species are recorded from within the forest and its immediate environment. We discuss the generalized zoogeography of the forest and distribution pattern of the taxa comment on the protection of the forest. Analysis of the reptile species composition shows Kakamega Forest to be similar to the Guinea-Congolian rainforest and is considered the easternmost remnant of this forest block. Kakamega forest has a high diversity value for Kenya and represents a diversity hotspot on a national scale. Two species, Lygodac- tylus gutturalis and Psammophis phillipsi, are recorded in Kenya for the first time. Several other first records and the description of a new species (Agamidae: Agama finchi) were published already separately. Keywords. East Africa, Kenya, Kakamega Forest, herpetological survey, checklist, national diversity hotspot. 1. INTRODUCTION In Africa tropical rainforests extend from southern Sene- covery and scientific descriptions. Uganda, for example gal in the west to the coastal forests of Kenya and Tanza- has lost 86 % of its original forest in the past two decades nia in the east (COLLINS 1992). The East African rainforests and the remaining parts are isolated fragments (VONESH belong to different biogeographical clades. -

From Southern Nigeria

SHORT NOTES HERPETOLOGJCAL JOURNAL, Vol. 12, pp. 179-182 (2002) the territories surveyed cf. Luiselli & Angelici, 2000), situated in the easternaxis of the Niger Delta (Bayelsa DIET OF THELOTORNIS KIR TL ANDII and Rivers States), in Anambra, Akwa-Ibom, Abia and (SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE: Cross River States. The study region is tropical, with a DISPHOLIDINI) FROM SOUTHERN wet season from May to September and a dry season fromOctober to April. The wettest period of the year is NIGERIA June-July, and the driest period between late December and February. GODFREY AKANI LUCA LUISELLI AND C. 1, 2•3 Methods used to survey the study area, capture FRANCESCO ANGELIC! M. 2·3 snakes and analyse their food items, are detailed else where (e.g. Luiselli et al., 1998, 2002). Fieldwork was 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, P.M.B. 5080, Port conducted under all climatic conditions, but with a bias Harcourt (R ivers State), Nigeria toward diurnalhours (from 0800-1800 hrs) due to secu rity constraints related to the prevailing unstable Centre of Environmental Studies "Demetra ", Via dei 2 political situation. Field effort was almost identical in Cochi 48/B, I-00133 Rome, Italy the wet (421 field days) and dry (418 field days) sea 3 F.I.Z. V., via Olona 7, I-00198 Rome, Italy sons. We searched for snakes along standardized routes in Key words: Africa, feeding ecology, snake the various microhabitats frequented by snakes at the study areas. We captured snakes by hand, but additional Th elotornis kirt/andii is an arboreal, venomous free-ranging specimens were captured by pitfall traps colubrid snake with a wide distribution ranging fromthe with drift fences and by traps used by locals to capture islands of the Bijagos Archipelago, Guinea Bissau; east terrestrial animals. -

Annotated Checklist and Provisional Conservation Status of Namibian Reptiles

Annotated Checklist - Reptiles Page 1 ANNOTATED CHECKLIST AND PROVISIONAL CONSERVATION STATUS OF NAMIBIAN REPTILES MICHAEL GRIFFIN BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM PRIVATE BAG 13306 WINDHOEK NAMIBIA Annotated Checklist - Reptiles Page 2 Annotated Checklist - Reptiles Page 3 CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION 5 METHODS AND DEFINITIONS 6 SPECIES ACCOUNTS Genus Crocodylus Nile Crocodile 11 Pelomedusa Helmeted Terrapin 11 Pelusios Hinged Terrapins 12 Geochelone Leopard Tortoise 13 Chersina Bowsprit Tortoise 14 Homopus Nama Padloper 14 Psammobates Tent Tortoises 15 Kinixys Hinged Tortoises 16 Chelonia GreenTurtle 16 Lepidochelys Olive Ridley Turtle 17 Dermochelys Leatherback Turtle 17 Trionyx African Soft-shelled Turtle 18 Afroedura Flat Geckos 19 Goggia Dwarf Leaf-toed Geckos 20 Afrogecko Marbled Leaf-toed Gecko 21 Phelsuma Namaqua Day Gecko 22 Lygodactylus Dwarf Geckos 23 Rhoptropus Namib Day Geckos 25 Chondrodactylus Giant Ground Gecko 27 Colopus Kalahari Ground Gecko 28 Palmatogecko Web-footed Geckos 28 Pachydactylus Thick-toed Geckos 29 Ptenopus Barking Geckos 39 Narudasia Festive Gecko 41 Hemidactylus Tropical House Geckos 41 Agama Ground Agamas 42 Acanthocercus Tree Agama 45 Bradypodion Dwarf Chameleons 46 Chamaeleo Chameleons 47 Acontias Legless Skinks 48 Typhlosaurus Blind Legless Skinks 48 Sepsina Burrowing Skinks 50 Scelotes Namibian Dwarf Burrowing Skink 51 Typhlacontias Western Burrowing Skinks 51 Lygosoma Sundevall’s Writhing Skink 53 Mabuya Typical Skinks 53 Panaspis Snake-eyed Skinks 60 Annotated -

Zimbabwe Zambia Malawi Species Checklist Africa Vegetation Map

ZIMBABWE ZAMBIA MALAWI SPECIES CHECKLIST AFRICA VEGETATION MAP BIOMES DeserT (Namib; Sahara; Danakil) Semi-deserT (Karoo; Sahel; Chalbi) Arid SAvannah (Kalahari; Masai Steppe; Ogaden) Grassland (Highveld; Abyssinian) SEYCHELLES Mediterranean SCruB / Fynbos East AFrican Coastal FOrest & SCruB DrY Woodland (including Mopane) Moist woodland (including Miombo) Tropical Rainforest (Congo Basin; upper Guinea) AFrO-Montane FOrest & Grassland (Drakensberg; Nyika; Albertine rift; Abyssinian Highlands) Granitic Indian Ocean IslandS (Seychelles) INTRODUCTION The idea of this booklet is to enable you, as a Wilderness guest, to keep a detailed record of the mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians that you observe during your travels. It also serves as a compact record of your African journey for future reference that hopefully sparks interest in other wildlife spheres when you return home or when travelling elsewhere on our fragile planet. Although always exciting to see, especially for the first-time Africa visitor, once you move beyond the cliché of the ‘Big Five’ you will soon realise that our wilderness areas offer much more than certain flagship animal species. Africa’s large mammals are certainly a big attraction that one never tires of, but it’s often the smaller mammals, diverse birdlife and incredible reptiles that draw one back again and again for another unparalleled visit. Seeing a breeding herd of elephant for instance will always be special but there is a certain thrill in seeing a Lichtenstein’s hartebeest, cheetah or a Lilian’s lovebird – to name but a few. As a globally discerning traveller, look beyond the obvious, and challenge yourself to learn as much about all wildlife aspects and the ecosystems through which you will travel on your safari. -

A New Species of the Acanthocercus Atricollis Complex (Squamata: Agamidae) from Zambia

SALAMANDRA 48(1) 21–30 30 AprilA new 2012 speciesISSN of Acanthocercus 0036–3375 from Zambia A new species of the Acanthocercus atricollis complex (Squamata: Agamidae) from Zambia Philipp Wagner 1,2, Eli Greenbaum 3 & Aaron Bauer 1 1) Department of Biology, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA 2) Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany 3) Department of Biological Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 West University Avenue, El Paso, Texas 79968, USA Corresponding author: Philipp Wagner, e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 27 November 2011 Abstract. In the course of working on a taxonomic revision of the Acanthocercus atricollis complex, we discovered a popu- lation from the Luangwa and Zambezi valleys in Zambia and adjacent Malawi that is morphologically and genetically dis- tinct from all described taxa of this complex. This population is described as a new species on the basis of morphological characters, including indistinct transverse rows of enlarged scales on the body, a large black patch on the shoulders, and a different pholidosis. It is morphologically similar toA. a. gregorii and A. a. loveridgei, but seems to be more closely related to the former. Key words. Squamata, Agamidae, Acanthocercus atricollis, new species, Africa, Zambia, Malawi, Zambezi Valley, Luangwa Valley. Introduction diet is dominated by ants and beetles, but other arthropods also play an important role (Reaney & Whiting 2002). The genus Acanthocercus Fitzinger, 1843 is widely dis- Whiting et al. (2009) identified A. a. atricollis as an an- tributed from the southwestern corner of the Arabian Pen- thropophilic species, with higher population densities in insula and the Horn of Africa to southern Africa. -

Patterns of Species Richness, Endemism and Environmental Gradients of African Reptiles

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Patterns of species richness, endemism ARTICLE and environmental gradients of African reptiles Amir Lewin1*, Anat Feldman1, Aaron M. Bauer2, Jonathan Belmaker1, Donald G. Broadley3†, Laurent Chirio4, Yuval Itescu1, Matthew LeBreton5, Erez Maza1, Danny Meirte6, Zoltan T. Nagy7, Maria Novosolov1, Uri Roll8, 1 9 1 1 Oliver Tallowin , Jean-Francßois Trape , Enav Vidan and Shai Meiri 1Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, ABSTRACT 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel, 2Department of Aim To map and assess the richness patterns of reptiles (and included groups: Biology, Villanova University, Villanova PA 3 amphisbaenians, crocodiles, lizards, snakes and turtles) in Africa, quantify the 19085, USA, Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, PO Box 240, Bulawayo, overlap in species richness of reptiles (and included groups) with the other ter- Zimbabwe, 4Museum National d’Histoire restrial vertebrate classes, investigate the environmental correlates underlying Naturelle, Department Systematique et these patterns, and evaluate the role of range size on richness patterns. Evolution (Reptiles), ISYEB (Institut Location Africa. Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite, UMR 7205 CNRS/EPHE/MNHN), Paris, France, Methods We assembled a data set of distributions of all African reptile spe- 5Mosaic, (Environment, Health, Data, cies. We tested the spatial congruence of reptile richness with that of amphib- Technology), BP 35322 Yaounde, Cameroon, ians, birds and mammals. We further tested the relative importance of 6Department of African Biology, Royal temperature, precipitation, elevation range and net primary productivity for Museum for Central Africa, 3080 Tervuren, species richness over two spatial scales (ecoregions and 1° grids). We arranged Belgium, 7Royal Belgian Institute of Natural reptile and vertebrate groups into range-size quartiles in order to evaluate the Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny, role of range size in producing richness patterns. -

Reptiles & Amphibians

AWF FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT : REVIEWS OF EXISTING BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION i Published for The African Wildlife Foundation's FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT by THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY and THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA 2004 PARTNERS IN BIODIVERSITY The Zambezi Society The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P O Box HG774 P O Box FM730 Highlands Famona Harare Bulawayo Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 747002-5 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.biodiversityfoundation.org Website : www.zamsoc.org The Zambezi Society and The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa are working as partners within the African Wildlife Foundation's Four Corners TBNRM project. The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa is responsible for acquiring technical information on the biodiversity of the project area. The Zambezi Society will be interpreting this information into user-friendly formats for stakeholders in the Four Corners area, and then disseminating it to these stakeholders. THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA (BFA is a non-profit making Trust, formed in Bulawayo in 1992 by a group of concerned scientists and environmentalists. Individual BFA members have expertise in biological groups including plants, vegetation, mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, aquatic invertebrates and ecosystems. The major objective of the BFA is to undertake biological research into the biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, and to make the resulting information more accessible. Towards this end it provides technical, ecological and biosystematic expertise. THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies. -

Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of the Maasai Mara

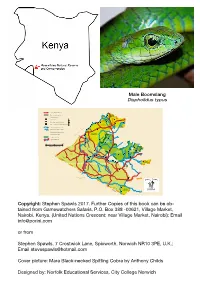

Male Boomslang Dispholidus typus N OLARE MOTOROGI CONSERVANCY OLARRO CONSERVANCY Copyright: Stephen Spawls 2017. Further Copies of this book can be ob- tained from Gamewatchers Safaris, P.O. Box 388 -00621, Village Market, Nairobi, Kenya, (United Nations Crescent; near Village Market, Nairobi); Email [email protected] or from Stephen Spawls, 7 Crostwick Lane, Spixworth, Norwich NR10 3PE, U.K.; Email [email protected] Cover picture: Mara Black-necked Spitting Cobra by Anthony Childs Designed by: Norfolk Educational Services, City College Norwich A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Maasai Mara Ecosystem By Printed by Stephen Spawls Norwich City College Print Room Contents Introduction 2 Foreword by Jake Grieves-Cook, 3 Chairman of Gamewatchers Safaris & Porini Camps Why conservation and the conservancies are important 4 Observing and Collecting Reptiles and Amphibians 5 Safety and Reptiles/Amphibians 7 Snakebite 8 The Maasai-Mara Ecosystem and its reptile 9 and amphibian fauna The Reptiles and Amphibians of the Maasai Mara ecosystem 10 Some species that might be found in the Maasai Mara 34 but are as yet unrecorded Acknowledgements 38 Further Resources 39 Introduction “The natural resources of this country – its wildlife which offers such an attraction to beautiful places…the mighty forests which guard the water catchment areas so vital to the survival of man and beast – are a priceless heritage for the future. The government of Kenya…pledges itself to conserve them for posterity with all the means at its disposal.” Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, First President of the Republic of Kenya (inscription at the entrance of Nairobi National Park 1964) As far as I am aware, this book is the first guide to the reptiles and amphibians of any large conservation area in Kenya. -

EJT-17-10 Stekolnikov

© European Journal of Taxonomy; download unter http://www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu; www.zobodat.at European Journal of Taxonomy 395: 1–233 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2018.395 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2018 · Stekolnikov A.A. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A244F97F-8CEB-40CE-A182-7E5440337CAA Taxonomy and distribution of African chiggers (Acariformes, Trombiculidae) Alexandr A. STEKOLNIKOV Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya embankment 1, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia. Email: [email protected] urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:576D9065-0E85-4C5C-B00F-B907E3005B95 Abstract. Chigger mites of the African continent are reviewed using data acquired from the literature and examination of the collections deposited at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren, Belgium) and the Natural History Museum (London, UK). All fi ndings for 443 valid chigger species belonging to 61 genera are reported, along with details on their collection locality and host species. Three new synonyms are proposed: Straelensia Vercammen-Grandjean & Kolebinova, 1968 (= Anasuscuta Brown, 2009 syn. nov.); Herpetacarus (Herpetacarus) Vercammen-Grandjean, 1960 (= Herpetacarus (Lukoschuskaaia) Kolebinova & Vercammen-Grandjean, 1980 syn. nov.); Gahrliepia brennani (Jadin & Vercammen-Grandjean, 1952) (= Gahrliepia traubi Audy, Lawrence & Vercammen-Grandjean, 1961 syn. nov.). A new replacement name is proposed: Microtrombicula squirreli Stekolnikov, 2017 nom. nov. pro Eltonella myonacis heliosciuri Vercammen-Grandjean, 1965 (praeocc. Vercammen-Grandjean, 1965). Ninety new combinations are proposed. Keys to subfamilies, genera and subgenera of African trombiculid larvae and diagnoses of these taxa are given. Keywords. Chigger mites, fauna, taxonomy, Africa. Stekolnikov A.A. 2018. Taxonomy and distribution of African chiggers (Acariformes, Trombiculidae).