Morphology, Locomotor Performance and Habitat Use In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nyika and Vwaza Reptiles & Amphibians Checklist

LIST OF REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS OF NYIKA NATIONAL PARK AND VWAZA MARSH WILDLIFE RESERVE This checklist of all reptile and amphibian species recorded from the Nyika National Park and immediate surrounds (both in Malawi and Zambia) and from the Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve was compiled by Dr Donald Broadley of the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, in November 2013. It is arranged in zoological order by scientific name; common names are given in brackets. The notes indicate where are the records are from. Endemic species (that is species only known from this area) are indicated by an E before the scientific name. Further details of names and the sources of the records are available on request from the Nyika Vwaza Trust Secretariat. REPTILES TORTOISES & TERRAPINS Family Pelomedusidae Pelusios rhodesianus (Variable Hinged Terrapin) Vwaza LIZARDS Family Agamidae Acanthocercus branchi (Branch's Tree Agama) Nyika Agama kirkii kirkii (Kirk's Rock Agama) Vwaza Agama armata (Eastern Spiny Agama) Nyika Family Chamaeleonidae Rhampholeon nchisiensis (Nchisi Pygmy Chameleon) Nyika Chamaeleo dilepis (Common Flap-necked Chameleon) Nyika(Nchenachena), Vwaza Trioceros goetzei nyikae (Nyika Whistling Chameleon) Nyika(Nchenachena) Trioceros incornutus (Ukinga Hornless Chameleon) Nyika Family Gekkonidae Lygodactylus angularis (Angle-throated Dwarf Gecko) Nyika Lygodactylus capensis (Cape Dwarf Gecko) Nyika(Nchenachena), Vwaza Hemidactylus mabouia (Tropical House Gecko) Nyika Family Scincidae Trachylepis varia (Variable Skink) Nyika, -

Zimbabwe Zambia Malawi Species Checklist Africa Vegetation Map

ZIMBABWE ZAMBIA MALAWI SPECIES CHECKLIST AFRICA VEGETATION MAP BIOMES DeserT (Namib; Sahara; Danakil) Semi-deserT (Karoo; Sahel; Chalbi) Arid SAvannah (Kalahari; Masai Steppe; Ogaden) Grassland (Highveld; Abyssinian) SEYCHELLES Mediterranean SCruB / Fynbos East AFrican Coastal FOrest & SCruB DrY Woodland (including Mopane) Moist woodland (including Miombo) Tropical Rainforest (Congo Basin; upper Guinea) AFrO-Montane FOrest & Grassland (Drakensberg; Nyika; Albertine rift; Abyssinian Highlands) Granitic Indian Ocean IslandS (Seychelles) INTRODUCTION The idea of this booklet is to enable you, as a Wilderness guest, to keep a detailed record of the mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians that you observe during your travels. It also serves as a compact record of your African journey for future reference that hopefully sparks interest in other wildlife spheres when you return home or when travelling elsewhere on our fragile planet. Although always exciting to see, especially for the first-time Africa visitor, once you move beyond the cliché of the ‘Big Five’ you will soon realise that our wilderness areas offer much more than certain flagship animal species. Africa’s large mammals are certainly a big attraction that one never tires of, but it’s often the smaller mammals, diverse birdlife and incredible reptiles that draw one back again and again for another unparalleled visit. Seeing a breeding herd of elephant for instance will always be special but there is a certain thrill in seeing a Lichtenstein’s hartebeest, cheetah or a Lilian’s lovebird – to name but a few. As a globally discerning traveller, look beyond the obvious, and challenge yourself to learn as much about all wildlife aspects and the ecosystems through which you will travel on your safari. -

Patterns of Species Richness, Endemism and Environmental Gradients of African Reptiles

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Patterns of species richness, endemism ARTICLE and environmental gradients of African reptiles Amir Lewin1*, Anat Feldman1, Aaron M. Bauer2, Jonathan Belmaker1, Donald G. Broadley3†, Laurent Chirio4, Yuval Itescu1, Matthew LeBreton5, Erez Maza1, Danny Meirte6, Zoltan T. Nagy7, Maria Novosolov1, Uri Roll8, 1 9 1 1 Oliver Tallowin , Jean-Francßois Trape , Enav Vidan and Shai Meiri 1Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, ABSTRACT 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel, 2Department of Aim To map and assess the richness patterns of reptiles (and included groups: Biology, Villanova University, Villanova PA 3 amphisbaenians, crocodiles, lizards, snakes and turtles) in Africa, quantify the 19085, USA, Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, PO Box 240, Bulawayo, overlap in species richness of reptiles (and included groups) with the other ter- Zimbabwe, 4Museum National d’Histoire restrial vertebrate classes, investigate the environmental correlates underlying Naturelle, Department Systematique et these patterns, and evaluate the role of range size on richness patterns. Evolution (Reptiles), ISYEB (Institut Location Africa. Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite, UMR 7205 CNRS/EPHE/MNHN), Paris, France, Methods We assembled a data set of distributions of all African reptile spe- 5Mosaic, (Environment, Health, Data, cies. We tested the spatial congruence of reptile richness with that of amphib- Technology), BP 35322 Yaounde, Cameroon, ians, birds and mammals. We further tested the relative importance of 6Department of African Biology, Royal temperature, precipitation, elevation range and net primary productivity for Museum for Central Africa, 3080 Tervuren, species richness over two spatial scales (ecoregions and 1° grids). We arranged Belgium, 7Royal Belgian Institute of Natural reptile and vertebrate groups into range-size quartiles in order to evaluate the Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny, role of range size in producing richness patterns. -

Reptiles & Amphibians

AWF FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT : REVIEWS OF EXISTING BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION i Published for The African Wildlife Foundation's FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT by THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY and THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA 2004 PARTNERS IN BIODIVERSITY The Zambezi Society The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P O Box HG774 P O Box FM730 Highlands Famona Harare Bulawayo Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 747002-5 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.biodiversityfoundation.org Website : www.zamsoc.org The Zambezi Society and The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa are working as partners within the African Wildlife Foundation's Four Corners TBNRM project. The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa is responsible for acquiring technical information on the biodiversity of the project area. The Zambezi Society will be interpreting this information into user-friendly formats for stakeholders in the Four Corners area, and then disseminating it to these stakeholders. THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA (BFA is a non-profit making Trust, formed in Bulawayo in 1992 by a group of concerned scientists and environmentalists. Individual BFA members have expertise in biological groups including plants, vegetation, mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, aquatic invertebrates and ecosystems. The major objective of the BFA is to undertake biological research into the biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, and to make the resulting information more accessible. Towards this end it provides technical, ecological and biosystematic expertise. THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies. -

Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of the Maasai Mara

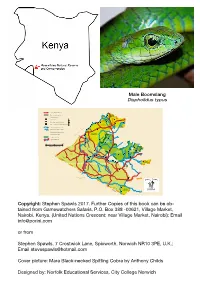

Male Boomslang Dispholidus typus N OLARE MOTOROGI CONSERVANCY OLARRO CONSERVANCY Copyright: Stephen Spawls 2017. Further Copies of this book can be ob- tained from Gamewatchers Safaris, P.O. Box 388 -00621, Village Market, Nairobi, Kenya, (United Nations Crescent; near Village Market, Nairobi); Email [email protected] or from Stephen Spawls, 7 Crostwick Lane, Spixworth, Norwich NR10 3PE, U.K.; Email [email protected] Cover picture: Mara Black-necked Spitting Cobra by Anthony Childs Designed by: Norfolk Educational Services, City College Norwich A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Maasai Mara Ecosystem By Printed by Stephen Spawls Norwich City College Print Room Contents Introduction 2 Foreword by Jake Grieves-Cook, 3 Chairman of Gamewatchers Safaris & Porini Camps Why conservation and the conservancies are important 4 Observing and Collecting Reptiles and Amphibians 5 Safety and Reptiles/Amphibians 7 Snakebite 8 The Maasai-Mara Ecosystem and its reptile 9 and amphibian fauna The Reptiles and Amphibians of the Maasai Mara ecosystem 10 Some species that might be found in the Maasai Mara 34 but are as yet unrecorded Acknowledgements 38 Further Resources 39 Introduction “The natural resources of this country – its wildlife which offers such an attraction to beautiful places…the mighty forests which guard the water catchment areas so vital to the survival of man and beast – are a priceless heritage for the future. The government of Kenya…pledges itself to conserve them for posterity with all the means at its disposal.” Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, First President of the Republic of Kenya (inscription at the entrance of Nairobi National Park 1964) As far as I am aware, this book is the first guide to the reptiles and amphibians of any large conservation area in Kenya. -

EJT-17-10 Stekolnikov

© European Journal of Taxonomy; download unter http://www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu; www.zobodat.at European Journal of Taxonomy 395: 1–233 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2018.395 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2018 · Stekolnikov A.A. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A244F97F-8CEB-40CE-A182-7E5440337CAA Taxonomy and distribution of African chiggers (Acariformes, Trombiculidae) Alexandr A. STEKOLNIKOV Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya embankment 1, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia. Email: [email protected] urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:576D9065-0E85-4C5C-B00F-B907E3005B95 Abstract. Chigger mites of the African continent are reviewed using data acquired from the literature and examination of the collections deposited at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren, Belgium) and the Natural History Museum (London, UK). All fi ndings for 443 valid chigger species belonging to 61 genera are reported, along with details on their collection locality and host species. Three new synonyms are proposed: Straelensia Vercammen-Grandjean & Kolebinova, 1968 (= Anasuscuta Brown, 2009 syn. nov.); Herpetacarus (Herpetacarus) Vercammen-Grandjean, 1960 (= Herpetacarus (Lukoschuskaaia) Kolebinova & Vercammen-Grandjean, 1980 syn. nov.); Gahrliepia brennani (Jadin & Vercammen-Grandjean, 1952) (= Gahrliepia traubi Audy, Lawrence & Vercammen-Grandjean, 1961 syn. nov.). A new replacement name is proposed: Microtrombicula squirreli Stekolnikov, 2017 nom. nov. pro Eltonella myonacis heliosciuri Vercammen-Grandjean, 1965 (praeocc. Vercammen-Grandjean, 1965). Ninety new combinations are proposed. Keys to subfamilies, genera and subgenera of African trombiculid larvae and diagnoses of these taxa are given. Keywords. Chigger mites, fauna, taxonomy, Africa. Stekolnikov A.A. 2018. Taxonomy and distribution of African chiggers (Acariformes, Trombiculidae). -

The Herpetofauna of the Langjan Nature Reserve (Limpopo Province

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2002 Band/Volume: 15_3_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Schmidt Almuth D. Artikel/Article: The herpetofauna of the Langjan Nature Reserve (Limpopo Province, Republic of South Africa) 121-135 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at HERPETOZOA 15 (3/4): 121 - 135 121 Wien, 30. Dezember 2002 The herpetofauna of the Langjan Nature Reserve (Limpopo Province, Republic of South Africa) (Amphibia, Reptilia) Die Herpetofauna des Langjan-Naturreservates (Provinz Limpopo, Republik Südafrika) (Amphibia, Reptilia) ALMUTH D. SCHMIDT KURZFASSUNG Das Langjan Naturreservat ist ein 4774 ha großes Schutzgebiet in der Limpopo Provinz Südafrikas, 130 km nördlich der Provinzhauptstadt Pietersburg gelegen. Während einer Feldstudie von Januar bis April 1998 und drei kürzeren Aufenthalten zwischen 1999 und 2001 konnten innerhalb des Schutzgebietes insgesamt 43 Reptilien- (3 Schildkröten, 23 Eidechsen, 17 Schlangen) und 7 Amphibienarten nachgewiesen werden. Die Anzahl der aus dem Gebiet bekannten Formen erhöht sich damit auf 47 bei den Reptilien und 10 bei den Amphibien. Die von der Autorin im Untersuchungsgebiet nachgewiesenen Arten werden hinsichtlich ihrer relativen Häufigkeit, ihrer allge- meinen Lebensraumansprüche und Verbreitung im Reservat charakterisiert. Neun weitere, bisher nur außerhalb der Reservatsgrenzen nachgewiesene Reptilienarten -

Tanzania Highlights of the North 1St to 11Th November 2019 (11 Days)

Tanzania Highlights of the North 1st to 11th November 2019 (11 days) Trip Report Grey-breasted Spurfowl by Nigel Redman Tour leader: Nigel Redman Trip Report compiled by Nigel Redman Trip Report – RBL Tanzania – Highlights of the North 2019 2 Tour Summary Northern Tanzania is the classic safari destination. It is one of the few places where birds take second place to the mammals. And for good reason too. We timed this new Highlights tour to perfection, arriving in the Seronera region of the Serengeti at the height of the Great Migration. At our isolated tented camp, we were surrounded day and night by braying wildebeest and zebras, and at night heard roaring Lions and laughing hyaenas as we tried to sleep. Apart from all this action, there were many other highlights, with no fewer than 32 Lions, three Leopards, two Cheetahs, a magnificent Serval (voted mammal of the trip), large herds of African Elephants, a new-born Impala calf that could barely stand up, and a wide range of typical African megafauna. And then there were the birds! There were so many highlights of these too, but pride of place must go to the endemics and near-endemics, including Grey-breasted Spurfowl, Fischer’s and Yellow-collared Serval by Nigel Redman Lovebirds, Tanzanian Red-billed Hornbill, Rufous-tailed and Taveta Weavers, Ashy Starling, Karamoja Apalis, Athi Short-toed Lark, Stripe-faced Greenbul, Broad-ringed White-eye, Kenrick’s Starling, and of course Beesley’s Lark. Top Birds Top Mammal Experiences 1st Grey Crowned Crane (14 points) 1st Serval (25 points) -

A Survey of Helminth Parasites of the Lizard, Agama Agama in Ile–Ife And

iolog ter y & c P a a B r f a o s i l Journal of Bacteriology and t o a Sowemimo and Oluwafemi, J Bacteriol Parasitol 2017, 8:1 l n o r g u y o DOI: 10.4172/2155-9597.1000303 J Parasitology ISSN: 2155-9597 Bacteriology and Parasitology Research Article Open Access A Survey of Helminth Parasites of the Lizard, Agama agama in Ile–Ife and Ibadan Southwest Nigeria Oluyomi Abayomi Sowemimo* and Temitope Ajoke Oluwafemi Department of Zoology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Oluyomi Abayomi Sowemimo, Department of Zoology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 17, 2017; Accepted date: March 07, 2017; Published date: March 13, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Sowemimo OA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract A parasitological survey was carried out between February and October, 2015 to determine the helminth fauna of the lizard, Agama agama from two locations Ibadan and Ile-Ife, Southwest Nigeria. A total of 133 specimens were collected and examined for helminth infections. The results showed that the overall prevalence of helminth infection in A. agama was 100%. Five species of helminths were recovered comprising three nematodes, Strongyluris brevicaudata (92.5%), Parapharyngodon sp. (89.5%) and unidentified nematode (0.8%), one species of cestode, Oochoristica truncata (56.4%) and one species of trematode, Mesocoelium monas (1.5%). -

Preliminary Herpetological Survey of Ngonye Falls and Surrounding Regions in South-Western Zambia 1,2,*Darren W

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 11(1) [Special Section]: 24–43 (e148). Preliminary herpetological survey of Ngonye Falls and surrounding regions in south-western Zambia 1,2,*Darren W. Pietersen, 3Errol W. Pietersen, and 4,5Werner Conradie 1Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, SOUTH AFRICA 2Research Associate, Herpetology Section, Department of Vertebrates, Ditsong National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 413, Pretoria, 0001, SOUTH AFRICA 3P.O. Box 1514, Hoedspruit, 1380, SOUTH AFRICA 4Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. Box 13147, Humewood, 6013, SOUTH AFRICA 5School of Natural Resource Management, George Campus, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, George, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—The herpetofauna of Zambia has been relatively well-studied, although most surveys were conducted decades ago. In western Zambia in particular, surveys were largely restricted to a few centers, particularly those along the Zambezi River. We here report on the herpetofauna of the Ngonye Falls and surrounding regions in south-western Zambia. We recorded 18 amphibian, one crocodile, two chelonian, 22 lizard, and 19 snake species, although a number of additional species are expected to occur in the region based on their known distribution and habitat preferences. We also provide three new reptile country records for Zambia (Long-tailed Worm Lizard, Dalophia longicauda, Anchieta’s Worm Lizard, Monopeltis anchietae, and Zambezi Rough-scaled Lizard, Ichnotropis grandiceps), and report on the second specimen of Schmitz’s Legless Skink, Acontias schmitzi, a species described in 2012 and until now known only from the holotype. This record also represents a 140 km southward range extension for the species. -

Sites and Species of Conservation Interest for the CESVI Project Area

SPECIES and SITES of CONSERVATION INTEREST for the CESVI PROJECT AREA, SOUTHERN ZIMBABWE edited by Rob Cunliffe October 2000 Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 7 SPECIES AND SITES OF CONSERVATION INTEREST FOR THE CESVI PROJECT AREA, SOUTHERN ZIMBABWE R. N. Cunliffe October 2000 Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 7 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe Species and Sites for Conservation in the Southern Lowveld i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................1 2. APPROACH ...........................................................1 3. SPECIES LISTS ........................................................2 3.1 Patterns of Diversity ...............................................2 4. SPECIES OF INTEREST .................................................3 5. SITES OF INTEREST....................................................3 6. FURTHER WORK REQUIRED............................................4 7. DISCUSSION ..........................................................4 7.1 Sites of Conservation Interest ........................................4 7.2 The Need for a Broader Overview.....................................5 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................5 9. REFERENCES .........................................................5 10. TABLES ..............................................................7 Table 1. Numbers of species of various taxa listed..............................7 Table 2. Numbers of species of -

Endoparasites (Cestoidea, Nematoda, Pentastomida) of Reptiles (Sauria, Ophidia) from the Republic of Namibia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232683383 Endoparasites (Cestoidea, Nematoda, Pentastomida) of Reptiles (Sauria, Ophidia) from the Republic of Namibia Article in Comparative Parasitology · January 2011 DOI: 10.1654/4467.1 CITATIONS READS 5 205 3 authors, including: Charles Bursey Paul Freed Pennsylvania State University Carnegie Museum Of Natural His… 482 PUBLICATIONS 4,347 CITATIONS 64 PUBLICATIONS 467 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Taxonomy and biology of nematode parasites of vertebrates (fish, amphibians and reptiles) View project North American Subterranean Biodiversity Work View project All content following this page was uploaded by Charles Bursey on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Endoparasites (Cestoidea, Nematoda, Pentastomida) of Reptiles (Sauria, Ophidia) from the Republic of Namibia Author(s): Chris T. McAllister, Charles R. Bursey, and Paul S. Freed Source: Comparative Parasitology, 78(1):140-151. 2011. Published By: The Helminthological Society of Washington DOI: 10.1654/4467.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1654/4467.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use.