Commercial Television Broadcasting: an Economic Analysis of Its Structure and Competitive Alternatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Holloway, Douglas V., 1954- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Douglas Holloway, Dates: December 13, 2013 Bulk Dates: 2013 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:10:46). Description: Abstract: Television executive Douglas Holloway (1954 - ) is the president of Ion Media Networks, Inc. and was an early pioneer of cable television. Holloway was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on December 13, 2013, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2013_322 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Television executive Douglas V. Holloway was born in 1954 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He grew up in the inner-city Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood. In 1964, Holloway was part of the early busing of black youth into white neighborhoods to integrate Pittsburgh schools. In 1972, he entered Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts as a journalism major. Then, in 1974, Holloway transferred to Emerson College, and graduated from there in 1975 with his B.S. degree in mass communications and television production. In 1978, he received his M.B.A. from Columbia University with an emphasis in marketing and finance. Holloway was first hired in a marketing position with General Foods (later Kraft Foods). He soon moved into the television and communications world, and joined the financial strategic planning team at CBS in 1980. -

Results 2017

RESULTS 2017 Results 2017 Films, television programs, production, distribution, exhibition, exports, video, new media May 2018 Results 2017 1. ELECTRONICS AND HOUSEHOLD SPENDING ON FILM, VIDEO, TV AND VIDEO GAMES .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. CINEMA ................................................................................................................................... 12 2.1. Attendance at movie theaters ............................................................................................ 13 2.2. Distribution ........................................................................................................................ 36 2.3. Movie theater audiences .................................................................................................... 51 2.4. Exhibition ........................................................................................................................... 64 2.5. Feature film production ...................................................................................................... 74 3. TELEVISION ............................................................................................................................ 91 3.1. The television audience ..................................................................................................... 92 3.2. Films on television ............................................................................................................ -

WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library White House Communications Agency (WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77 WHCA selectively created, or acquired, videorecordings of news and public affairs broadcasts from the national networks CBS, NBC, and ABC; the public broadcast station WETA in Washington, DC; and various local station affiliates. Program examples include: news special reports, national presidential addresses and press conferences, local presidential events, guest interviews of administration officials, appearances of Ford family members, and the 1976 Republican Convention and Ford-Carter debates. In addition, WHCA created weekly compilation tapes of selected stories from network evening news programs. Click here for more details about the contents of the "Weekly News Summary" tapes All WHCA videorecordings are listed in the table below according to approximate original broadcast date. The last entries, however, are for compilation tapes of selected television appearances by Mrs. Ford, 1974-76. The tables are based on WHCA’s daily logs. “Tape Length” refers to the total recording time available, not actual broadcast duration. Copyright Notice: Although presidential addresses and very comparable public events are in the public domain, the broadcaster holds the rights to all of its own original content. This would include, for example, reporter commentaries and any supplemental information or images. Researchers may acquire copies of the videorecordings, but use of the copyrighted portions is restricted to private study and “fair use” in scholarship and research under copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code). Use the search capabilities of your PDF reader to locate specific names or keywords in the table below. -

Guidelines on Communications Strategies for the Transition from Analogue to Digital Terrestrial Broadcasting

2014-2017 Guidelines ITU-D Study Group 1 Question 8/1 International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Development Bureau Guidelines on Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 Communications Switzerland www.itu.int Strategies for the Transition from Analogue to Digital Terrestrial Broadcasting 6th Study Period 2014-2017 EXAMINATION OF STRATEGIES AND METHODS OF MIGRATION FROM ANALOGUE TO DIGITAL TERRESTRIAL BROADCASTING AND IMPLEMENTATION OF NEW SERVICES OF NEW AND IMPLEMENTATION BROADCASTING TERRESTRIAL DIGITAL TO ANALOGUE FROM AND METHODS OF MIGRATION OF STRATEGIES EXAMINATION ISBN 978-92-61-24801-7 QUESTION 8/1: QUESTION 9 7 8 9 2 6 1 2 4 8 0 1 7 Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2017 07/2017 International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) Office of the Director Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 – Switzerland Email: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5035/5435 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Deputy to the Director and Infrastructure Enabling Innovation and Partnership Project Support and Knowledge Director,Administration and Environmnent and Department (IP) Management Department (PKM) Operations Coordination e-Applications Department (IEE) Department (DDR) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5784 Tel.: +41 22 730 5421 Tel.: +41 22 730 5900 Tel.: +41 22 730 5447 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Africa Ethiopia Cameroon Senegal Zimbabwe International Telecommunication Union internationale des Union internationale des International Telecommunication Union (ITU) télécommunications (UIT) télécommunications (UIT) Union (ITU) Regional Office Bureau de zone Bureau de zone Area Office P.O. -

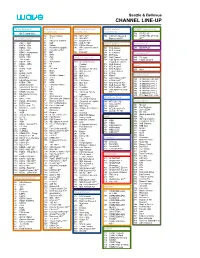

Channel Lineup

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

Cablelabs Studio Code List 05/01/2006

CableLabs Studio Code List 05/01/2006 Studio Name Code Last Update 05/05/2006 1 120 Degree Films 120D 2 1st National FSN 3 2 Silks Releasing 2SR 4 20th Century Fox FOX 5 21st Century 21ST 6 2nd Generation 2GN 7 4th & Broadway 4TH 8 50th Street 50TH 9 7th Planet Prods 7PP 10 8X Entertainment 8X 11 A.D.G. ADG 12 A.I.P. Studios AIPS 13 Abramorama Entertainment ABR 14 Academy ACD 15 Access Motion Picture Group ACM 16 ADV Films ADV 17 AFD Theatrical AFDT 18 Alive ALV 19 Alliance Atlantis Communications AA 20 Alliance International Pictures AIP 21 Almi ALM 22 American International Pictures AINT 23 American Vacation Production AVP 24 American World Pictures AWP 25 American Zoetrope AZO 26 Amoon AMO 27 Andora Pictures AND 28 Angelika ANG 29 A-Pix APIX 30 Apollo APO 31 Apple and Honey Film Corp. AHFC 32 Arab Films ARAB 33 Arcangelo Entertainment ARC 34 Arenaplex ARN 35 Arenas Entertainment ARNS 36 Aries ARI 37 Ariztical Entertainment ARIZ 38 Arrival Pictures ARR 39 Arrow Releasing ARW 40 Arthouse Films AHF 41 Artificial Eye ARTI 42 Artisan ARTS 43 Artist View Ent. ARV 44 Artistic License ARTL 45 Artists Releasing Corp ARP 46 ArtMattan Productions AMP 47 Artrution Productions ART 48 ASA Communications ASA 49 Ascot ASC 50 Associated Film Distribution AFD 51 Astor Pictures AST 1 CableLabs Studio Code List 05/01/2006 Studio Name Code Last Update 05/05/2006 52 Astral Films ASRL 53 At An Angle ANGL 54 Atlantic ATL 55 Atopia ATP 56 Attitude Films ATT 57 Avalanche Films AVF 58 Avatar Films AVA 59 Avco Embassy AEM 60 Avenue AVE 61 B&W Prods. -

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

Preliminary Injunction (“Pls.’ Mem.”) at 4

Case 1:10-cv-07415-NRB Document 35 Filed 02/22/11 Page 1 of 59 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------X WPIX, Inc., WNET.ORG, AMERICAN BROADCASTING COMPANIES, INC., DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC., MEMORANDUM AND CBS BROADCASTING INC, O R D E R CBS STUDIOS INC., THE CW TELEVISION STATIONS INC., 10 Civ. 7415 (NRB) NBC UNIVERSAL, INC., NBC STUDIOS, INC., UNIVERSAL NETWORK TELEVISION,LLC, TELEMUNDO NETWORK GROUP LLC, NBC TELEMUNDO LICENSE COMPANY, OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF BASEBALL, MLB ADVANCED MEDIA, L.P., COX MEDIA GROUP, INC., FISHER BROADCASTING-SEATTLE TV, L.L.C., TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION, FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC., TRIBUNE TELEVISION HOLDINGS, INC., TRIBUNE TELEVISION NORTHWEST, INC., UNIVISION TELEVISION GROUP, INC., THE UNIVISION NETWORK LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, TELEFUTURA NETWORK, WGBJ EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION, THIRTEEN, And PUBLIC BROADCASTING SERVICE, Plaintiffs, - against - ivi, Inc. and Todd Weaver, Defendants. ------------------------------------X NAOMI REICE BUCHWALD UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE Plaintiffs, major copyright owners in television programming, have moved to preliminarily enjoin defendants ivi, 1 Case 1:10-cv-07415-NRB Document 35 Filed 02/22/11 Page 2 of 59 Inc. (“ivi,” with a lowercase “i”) and its chief executive officer, Todd Weaver (“Weaver”), from streaming plaintiffs’ copyrighted television programming over the Internet without their consent. Since plaintiffs have demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits, irreparable harm should -

Loopstick Transplant * Walter Cronkite RIP * Profile; the Mighty KBC * Lord

September 2009 Volume 55 No. 04 ♣ Loopstick transplant ♣ Walter Cronkite RIP ♣ Profile; the mighty KBC ♣ Lord Haw Haw microphone ♣ Summer DX-pedition ♣ Flag antenna amplifier Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk Andy Robins KB8QGF, 1529 Miles Avenue, Kalamazoo, MI 49001, USA [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees.