Barry Farm by Joy Sharon Yi B.F.A. in Television and Broadcast Journalism, May 2011, Chapman University a Thesis Submitted to T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Housing Authority Organizational Chart 2/10/2014

District of Columbia Housing Authority Organizational Chart 2/10/2014 Board of Commissioners Executive Director General Counsel/ Chief of Staff Legal Affairs Human Audit and Board Relations Resources/ Compliance Labor Relations Fair Hearings Resident Capital Programs Services Asset Planning Management Housing Choice Public Affairs Voucher Program Deputy Executive Deputy Executive Director Director Operations Financial Management Client Placement/ Public Housing Administrative Information Public Safety ADA/504 Finance Recertification Operations Services Technology Attachment 1 - DCHA FY15 Response to pre-hearing questions District of Columbia Housing Authority Departments ADA/504 Program Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act mandates that federal fund recipients such as the District of Columbia Housing Authority (DCHA), ensure that their programs are accessible to qualified individuals with disabilities. Section 504 also requires DCHA to ensure that individuals with physical and mental disabilities have the opportunity to participate equally in programs and activities. Administrative Services The Office of Administrative Services assures that supplies, services, and construction are procured efficiently, effectively, and at the most favorable prices available to DCHA; and: promotes competition in contracting; provides safeguards for maintaining a procurement system of quality and integrity; and assures that DCHA purchasing actions are in full compliance with applicable federal standards, HUD regulations, and District of Columbia laws. Office of Audit and Compliance The Office of Audit and Compliance is an independent appraisal function established to examine and evaluate DCHA’s activities as a service to the agency. The OAC serves the DCHA by helping to identify and reduce risks; ensuring policies, procedures, laws and regulations are followed, established standards are met, resources are used efficiently and effectively, and DCHA objectives are achieved. -

BARRY FARM TENANTS and ALLIES ASSOCIATION, PETITIONER, 04/26/2018 V

Notice: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the Atlantic and Maryland Reporters. Users are requested to notify the Clerk of the Court of any formal errors so that corrections may be made before the bound volumes go to press. DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COURT OF APPEALS No. 15-AA-1000 BARRY FARM TENANTS AND ALLIES ASSOCIATION, PETITIONER, 04/26/2018 v. DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ZONING COMMISSION, RESPONDENT, and ± A&R DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, ET AL., INTERVENORS. Petition for Review of a Decision of the District of Columbia Zoning Commission (ZC-14-02) (Argued September 28, 2016 Decided April 26, 2018) Aristotle Theresa for petitioner Barry Farm Tenants and Allies Association. Paul J. Kiernan for intervenor A&R Development Corporation. Kyrus L. Freeman and Kristina A. Crooks were on the brief for A&R Development Corporation. ± The District of Columbia Housing Authority and Preservation of Affordable Housing were the other intervenors. 2 Karl A. Racine, Attorney General for the District of Columbia, Todd S. Kim, Solicitor General at the time the brief was filed, Loren L. AliKhan, Deputy Solicitor General at the time the brief was filed, and Richard S. Love, Senior Assistant Attorney General, filed a statement in lieu of brief for respondent. George R. Keys, Jr., filed a statement in lieu of brief for intervenor Preservation of Affordable Housing, Inc. + Before BLACKBURNE-RIGSBY, Chief Judge, MCLEESE, Associate Judge, and * KRAVITZ, Associate Judge of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia. Opinion for the court by Chief Judge Blackburne-Rigsby. Concurring opinion by Chief Judge Blackburne-Rigsby at page 41. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Barry Farm Dwellings Other Names/Site Number N/A

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Barry Farm Dwellings other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number not for publication 1100-1371 Stevens Road SE; 2677-2687 Wade Road SE; 2652 Firth Sterling Avenue SE city or town Washington DC vicinity state DC code DC county N/A code 001 zip code 20011 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

State of Washington, D.C.'S Neighborhoods A-3

State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods Prepared by Peter A. Tatian G. Thomas Kingsley Margery Austin Turner Jennifer Comey Randy Rosso Prepared for The Office of Planning The Government of the District of Columbia September 30, 2008 The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 UI project no. 08040-000-01 State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................... ii Acknowledgments............................................................................................. vi About this Report ............................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction...................................................................................................... 3 II. Demographics................................................................................................. 9 Population......................................................................................................................9 Households..................................................................................................................13 III. Economy – Jobs and Income ..................................................................... 15 Employed Residents and Unemployment Rate...........................................................15 Poverty and Household Income ..................................................................................18 Public Assistance -

REFLECTIONS Washington’S Southeast / Southwest Waterfront

REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Copyright © 2021 by Square 656 Owner, LLC Front cover image: Rendering of the Frederick Douglass Memorial ISBN: 978-0-578-82670-7 Bridge. The bridge connects the two shores of Designed by LaserCom Design, Berkeley CA the Anacostia River and is named after a former slave and human rights leader who became one of Washington’s most famous residents. District Department of Transportation vi FOREWORD REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Marjorie Lightman, PhD William Zeisel, PhD CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront QED Associates LLC Washington, DC CAMBRIA HOTEL n REFLECTIONS vii Then ... A gardener’s residence on the site of the Cambria Hotel. The flat-roofed frame house, 18 feet wide and costing $1,800 to construct more than a century ago, was home to Samuel Howison, a market gardener. The cornice at the top of the building now graces the Cambria Hotel’s lobby, and a fireplace mantle accents the rooftop bar. Peter Sefton Now ... The Cambria Hotel at 69 Q Street SW, a part of the Southeast/Southwest waterfront’s renaissance. Donohoe Welcome to the Cambria Hotel Located in an historic part of one of the world’s great cities. ashington is a star-studded town where money and influence glitter on a world stage of W24/7 news bites. Images of the White House, the Capitol, and the Mall are recognized around the world as synonymous with majesty and power. Washington, the nation’s capital, shapes our times and history. -

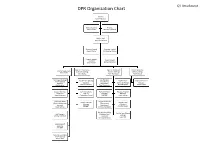

DPR Organization Chart

Q1 Attachment DPR Organization Chart Director Keith Anderson General Counsel Finance Amy Caspari Marjorie Edmonds Chief of Staff Jason Yuckenberg Program Analyst Program Analyst Angela Tucker Christopher Ashton Program Support Policy Analyst Assistant Michael Beckham Ikisha Walker Dep. Dir. Community Dep. Dir. Recreation Human Resources Chief of Operations Outreach (Acting) Services (Acting) Officer (Acting) Chris Carew John Stokes Toni Thompson Kwelli Sneed Planning and Design Sup Rec Spec Sup Rec Spec (Roving Sup Rec Spec Human Resources Officer (Capital (Community Leaders) (Seniors) (Acting) Manager Projects) Recreation) Alonzo Holloway Danielle Creek Kwelli Sneed Ella Faulkner Toni Thompson Support Services Communications Parks and Policy Aquatics Program Supervisor Director Manager Manager Steve Anderson Gwendolyn Crump VACANT Tyrell Lashley Sup Prgrm Mntr Sup Rec Therapist Permits Services Sup Rec Spec (Food and Nutrition (Therapeutic Manager (Athletics) Services) Recreation) VACANT Jennifer Moore Mark McCain Victoria Cole Rolon Sup Rec Spec (Early Sup Rec Spec (Teens) Risk Manager Childhood and (Acting) Michael Lightfoot Seasonal) Louis Hall Vanessa Gerideau Supervisory IT Specialist VACANT Partnership and Dev. Officer (Acting) Nicole Sims DPR List of Employees HQ- Operations Name Job Title adams,james RECREATION SPECIALIST Albornoz,Leo E HISPANIC PGM SPEC Alexander,Keely RECREATION SPEC Allen,Marcus R Program Analyst Anderson,Keith A Acting Director Anderson,Steven C SUPPORT SRVS SUPV Anthony,Keneysha Management Liaison Specialist Apaez,Andres Materials Handler Ashton,Christopher M Program Analyst Atkinson,Cedric T Park Ranger Baker,Natasha D STAFF ASSISTANT Beckham,Michael T Program Analyst Bell Willett,Lacretia D PARK RANGER Black,Walter Facility Manager Brown,Xavier Wesley Small Parks Specialist Burns,Yvonne Materials Handler Carew,Christopher J. -

Barry Farm Redevelopment Plan

Barry Farm | Park Chester | Wade Road Redevelopment Plan Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................. 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................. 6 HUMAN CAPITAL PLAN................................. 10 Master Planning Process .............................10 Human Capital Findings ..............................10 Recommended Priorities, Strategies and Outcomes ............................13 Human Capital Budget ................................14 PhYSICAL PLAN...........................................16 Existing Conditions .....................................17 Market Analysis Conclusions ......................18 The Vision .....................................................25 Urban Design Conclusions ..........................35 DeVELOPMENT AND FINANCE STRATEGY....................................................38 Development Plan, Site Control and Phasing ..................................................38 Funding Strategy .........................................39 Executive Summary The Redevelopment Plan for the Barry Farm/ Park Chester/Wade Road community (‘the Neighborhood’) consists of three elements – a Human Capital Plan, a Physical Plan and a Development and Finance Strategy. Founded on the principles of the New Communities Initiative, the redevelopment of this important southeast community shall to include the “human architecture” along with the physical architecture. Current families shall be supported and have the tools necessary to prosper and flourish as their neighborhood is -

State of Washington, D.C.'S Neighborhoods, 2010

2010 Prepared by Jennifer Comey Chris Narducci Peter A. Tatian Prepared for The Office of Planning The Government of the District of Columbia November 2010 The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 Copyright © November 2010. The Urban Institute. All rights reserved. Except for short quotes, no part of this report may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the Urban Institute. The Urban Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research and educational organization that examines the social, economic, and governance problems facing the nation. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods iii CONTENTS About this Report ............................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 5 II. Demographics ................................................................................................. 7 Population ................................................................................................................... 7 Households ................................................................................................................12 III. Economy—Jobs and Income ..................................................................... -

Emerging Corridors + Opportunity Zones 2019 Edition

EMERGING CORRIDORS + OPPORTUNITY ZONES 2019 EDITION In Public-Private Partnership with IMAGE COURTESY OF MENKITI GROUP COURTESY IMAGE The Washington DC Economic Partnership would like to acknowledge our public and private sector board members whose continued financial support and guidance has made the 2019 Emerging Corridors + Opportunity Zones publication possible. PUBLIC SECTOR PARTNERS OFFICE OF THE CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER PRIVATE SECTOR PARTNERS BOARD MEMBERS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Raj Aggarwal Timothy Duggan Lindsey Parker Board Chairman, Think Local First Senior Vice President and Commercial Acting Chief Technology Officer, Brian Kenner / Co-Chair Joseph Askew Regional Group Manager, OCTO Deputy Mayor, Vice President, Government Relations, TD Bank William Rich Office of Planning and Verizon Daniel Duke President, Delta Associates Economic Development Kristina Bouweiri Prinicipal Mid-Atlantic Region, Jennifer Rudy Richard Lake / Co-Chair President & CEO, Reston Limo Bohler Engineering Director, U.S. Office of Civic Innovation, Managing Principal, Steven Boyle Josh Etter Microsoft Roadside Development Managing Director, Director, Development, Chase W. Rynd Foulger Pratt Omar McIntosh / Vice Chair EDENS Executive Director, Senior Vice President, Jean-Luc Brami Angie Gates National Building Museum Smoot Construction Vice President, Gelberg Signs Director, OCTFME Tara Scanlon Stan Jackson Partner, Holland & Knight Jennifer Eugene / Secretary Kenneth Brewer President & CEO, AEDC Manager, Engineered Sales Executive Director, H Street CDC -

The 11Th Street Bridge Park Baseline Health Assessment

The 11th Street Bridge Park Baseline Health Assessment Presented to: Scott Kratz, 11th Street Bridge Park Director Prepared by: Mills Wallace, MPH Loretta DiPietro, PhD MPH Milken Institute School of Public Health The George Washington University Washington, DC Funded by: The Kresge Foundation A. Executive Summary Despite Washington, DC being the capital of the United States, the differences between the city’s eight geographic wards in education, income, and public resources are noteworthy. The 11th Street Bridge Park is unique in that it will link one of the more affluent regions of DC (Ward 6) to the lowest income region of the city (Ward 8). Building Bridges across the River (BBAR) at THEARC is a non-profit agency housed in Congress Heights that oversees the 11th Street Bridge Park in achieving the following primary goals: 1) build a healthy community in the neighborhoods surrounding the Bridge Park; 2) restore health to the Anacostia River; 3) enhance connection between the Ward 6 and Ward 8 communities; and 4) become an anchor for equitable and inclusive economic development in the surrounding communities. In that regard, BBAR formed three primary groups associated with the Bridge Park: 1) a Design Oversight Committee to inform a nation-wide design competition; 2) an Arts and Culture Committee to shape on-going programming; and 3) an Equitable Development Task Force to ensure nearby residents can continuously benefit from this new civic space. Each committee is comprised of local residents, business owners, government representatives, and faith communities. The Director of the 11th Street Bridge Park is Scott Kratz. -

DISTRICT of COLUMBIA HOUSING AUTHORITY 2019 OVERSIGHT and PERFORMANCE HEARING Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization Responses to Pre-Hearing Questions

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HOUSING AUTHORITY 2019 OVERSIGHT AND PERFORMANCE HEARING Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization Responses to Pre-Hearing Questions General Questions 1. Please provide a current organizational chart for the agency, including the number of vacant, frozen, and filled positions in each division or subdivision. Include the names and titles of all senior personnel and note the date that the information was collected on the chart. a. Please provide an explanation of the roles and responsibilities of each division and subdivision. b. Please provide a narrative explanation of any changes to the organizational chart made during the previous year. See Attachment 1 – Organizational Chart and Department Descriptions 2. Please provide a current Schedule A for the agency which identifies each position by program and activity, with the employee’s title/position, salary, fringe benefits, and length of time with the agency. Please note the date that the information was collected. The Schedule A should also indicate if the position is continuing/term/temporary/contract or if it is vacant or frozen. Please separate salary and fringe and indicate whether the position must be filled to comply with federal or local law. See Attachment 2 – Position Listing 3. Please list all employees detailed to or from your agency. For each employee identified, please provide the name of the agency the employee is detailed to or from, the reason for the detail, the date of the detail, and the employee’s projected date of return. Not Applicable 4. For FY19 and FY20, to date, please list all intra-District transfers to or from the agency.