A Speculative and Realist Photography?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Realism and Representation: on the Ontological Turn

DANIEL SACILOTTO that is, which unquestioningly privileges a certain temporal modality in its understanding of being. EALISM AND EPRESENTATION R R The existential analytic of Dasein carried forth by ON THE ONTOLOGICAL TURN phenomenology is thereby supposed to supplant the representational account of reason advanced by critique, suspending the equation of being and §1 - THE TWO MEANINGS OF THE “ONTOLOGICAL TURN” substance to which Kant would have remained be- holden to.4 This investigation is said to be ontological The views associated with the title “speculative then not in overcoming the question of access or realism” are often coordinated with a so-called in having resolved the quandaries concerning the “ontological turn” that is said to have taken place relation between man and the world. Rather, it purg- in recent Continental philosophy.1 Yet it is rather es this problematic from philosophical centrality unclear what exactly such a turn is supposed to by showing how the question about the disclosure entail. If, as Meillassoux argues, it is Kant’s name of being is necessarily propadeutic to the question that sets the horizon for the anti-realist denouement about the knowing of being. But since Dasein’s own that presumably characterizes both correlationism being is defined by being the agent of this disclosure, and idealism, then something like the overcoming phenomenology is nothing but fundamental ontology. of the critical turn in philosophy would seem to be At the end of this vector of radicalization, we see the centrally at stake.2 The turn towards ontology pro- repeated operation of a “hermeneutics of suspicion,” posed by the new realists would then be the obverse progressively revealing further prejudices in the of a turning away from Kantian epistemology and philosophical text, pushing critique towards the its implications. -

Dr. Christine Daigle (Brock University) Books 8. Rethinking the Human

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS – Dr. Christine Daigle (Brock University) Books 8. Rethinking the Human: Posthuman Vulnerability and its Ethical Potential. (in preparation). 7. Nietzsche as Phenomenologist. (submitted and under review at Edinburgh University Press). 6. Posthumanisms Through Deleuze. Christine Daigle and Terrance McDonald (eds.) (submitted and under review at Indiana University Press). 5. Nietzsche and Phenomenology: Power, Life, Subjectivity. Élodie Boublil and Christine Daigle (eds.), Studies in Continental Thought Series, Indiana University Press, 2013. 4. Jean-Paul Sartre. London: Routledge. Critical Thinkers Series, 2009. 3. Beauvoir and Sartre: The Riddle of Influence. Christine Daigle and Jacob Golomb (eds.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009. 2. Existentialist Thinkers and Ethics. Christine Daigle (ed.). Kingston and Montreal: McGill/Queen’s University Press, 2006. 1. Le nihilisme est-il un humanisme? Étude sur Nietzsche et Sartre. Sainte-Foy: Presses de L’Université Laval, 2005. Chapters in books 21. “Fascism and the Entangled Subject, or How to Resist Fascist Toxicity.” In Rosi Braidotti, Simone Bignall, Christine Daigle, Rick Dolphijn, Zeynep Gambetti, Woosung Kang, John Protevi, and Gregory J. Seigworth. How to Live the Anti- Fascist Life and Endure the Pain. New York: Columbia University Press (forthcoming 2020). 20. “Simone de Beauvoir.” Handbook of Phenomenology. Burt C. Hopkins and Claudio Majolino (eds.), London: Routledge (forthcoming 2020). 19. “Unweaving the Threads of Influence: Beauvoir and Sartre.” A Companion to Simone de Beauvoir. Nancy Bauer and Laura Hengehold (eds.), Oxford: Wiley- Blackwell, 2017, 260-270. 18. “Trans-subjectivity/Trans-objectivity.” Feminist Phenomenology Futures. Helen Fielding and Dorothea Olkowski (eds.), Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017, 183-199. 17. “Beauvoir and the Meaning of Life: Literature and Philosophy as Human Engagement in the World.” Feminist Philosophies of Life. -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Dimensional Investment Group

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2008-04-29 | Period of Report: 2008-02-29 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-08-027772 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC/ Business Address 1299 OCEAN AVE CIK:861929| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1130 11TH FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06067 | Film No.: 08784216 SANTA MONICA CA 90401 2133958005 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-6067 DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Catherine L. Newell, Esquire, Vice President and Secretary Dimensional Investment Group Inc., 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 310-395-8005 Date of fiscal year end: November 30 Date of reporting period: February 29, 2008 ITEM 1. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS. Dimensional Investment Group Inc. Form N-Q February 29, 2008 (Unaudited) Table of Contents Definitions of Abbreviations and Footnotes Schedules of Investments U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio II U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio III LWAS/DFA U.S. High Book to Market Portfolio DFA International Value Portfolio Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

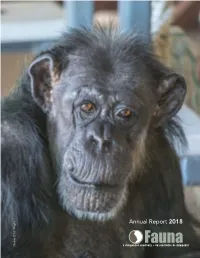

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future

Annual Report 2018 Blackie © NJ Wight Help Us Secure Their Future HelpLIFETIME CAREUs FUND Secure Their Future Established in 2007, the Fauna Lifetime Care Fund is our promise to the Fauna chimpanzees for a lifetime of the quality care they so deserve. MONTHLY DONATION Please email us at [email protected] to set up this form of monthly giving via cheque or credit card. ONLINE • CanadaHelps.org, enter the searchtype, charity name: Fauna Foundation and it will take you directly to the link. • FaunaFoundation.org, donate via PayPal PHONE 450-658-1844 FAX 450-658-2202 MAIL Fauna Foundation 3802 Bellerive Carignan,QC J3L 3P9 They need our help—not just today but tomorrow too. Toby © Jo-Anne McArthur Toby Help me keep my promise to them. Your donation today in whatever amount you can afford means so much! Billing Information Payment Information Name: ________________________________________________ o $100 o $75 o $50 o $25 o Other $ ______ Address: ______________________________________________ o Check enclosed (payable to Fauna) City: ___________________Province/State: _________________ o Visa o Mastercard Postal Code/Zip Code:__________________________________ o o Tel: (____)_____________________________________________ Monthly pledge $ ______ Lifetime Care Fund $ ______ Email: ________________________________________________ Card Number: ______________________________________ In o honor of or in o memory of ___________________________ Exp: ___/___/___ Signature: __________________________ Or give online at www.faunafoundation.org -

Moses Mendelssohn's Speculative Realism

PROBLEMI INTERNATIONAL,Inside, The Real: Moses vol. 2, Mendelssohn’sno. 2, 2018 © Society Speculative for Theoretical Realism Psychoanalysis Inside, The Real: Moses Mendelssohn’s Speculative Realism Yuval Kremnitzer In his influential book After Finitude (2008), Quentin Meil- lassoux argues for a new absolute, up-to-date with the 21 st century—absolute contingency. There is only one thing we can know to be true completely independently of us and our modes of representing or constituting the world around us—that there is no underlying reason for being (factuality), and, therefore, nothing to guarantee any sort of necessity, except the necessity of contingency. In the jargon of Western backpackers to India, “everything is possible.” What makes Meillassoux’s book repre- sentative of a larger and rather disorienting moment in philosophy is the way he here captures an underlying desire common to many contemporaries: the desire to break out of the confinements of what he labels “correlationism”—the modern inability to think being outside its correlation with thinking, the inability, that is, to explore being as such, in and of itself, in its utter indifference to human experience: For it could be that contemporary philosophers have lost the great outdoors, the absolute outside of pre-critical thinkers: that outside which was not relative to us, and which was given as indifferent to its own givenness to be what it is, existing in itself regardless of whether we are thinking of it or not; that outside which thought could explore with the legitimate feeling of being on foreign terri- tory—of being entirely elsewhere. -

Meillassoux, Correlationism, and the Ontological Difference G

PhænEx 12, no. 2 (winter 2018): 1-12 © 2018 G. Anthony Bruno Meillassoux, Correlationism, and the Ontological Difference G. ANTHONY BRUNO The realist credentials of post-Kantian philosophy are often disputed by those who worry that grounding ontology on the human standpoint— variously construed by Kant, German idealism, phenomenology, and existentialism—bars us from an otherwise accessible reality, impoverishing our cognitive grasp, and betraying the promise of natural science. While many such critics ally with the so-called analytic tradition, the past decade has seen the rise of thinkers versed in the so-called continental tradition who, under the loose and controversial banner of “speculative realism,” seek to overcome the alleged anthropocentrism of Kantian and post-Kantian thought by developing theories of cognitive access to human-transcendent being. Although proponents of speculative realism include Ray Brassier, Levi Bryant, Iain Hamilton Grant, and Graham Harman, my focus will be on Quentin Meillassoux, whose work has been influential both within this movement and for its sympathizers. It is Meillassoux who coins “correlationism” to name the view that we can only access the mutual dependence of thought and being and that, consequently, neither is explicable in isolation, even by the natural sciences (Meillassoux 5). And it is Meillassoux who, in his monograph After Finitude, traces correlationism to Kant’s Copernican revolution and claims its apotheosis to include Heidegger’s phenomenological claim that an understanding of being cannot dispense with an existential analysis of subjectivity. On this view, the question of being is inextricably bound to the question of the meaning of being for such beings as ourselves. -

Martin Pj Edwardes an Anthropological Perspective

The Origins of Self explores the role that selfhood plays in defining human society, and each human individual in that society. It considers the genetic and cultural origins of self, the role that self plays in socialisation and language, and the types of self we generate in our individual journeys to and through adulthood. Edwardes argues that other awareness is a relatively early evolutionary development, present throughout the primate clade and perhaps beyond, but self-awareness is a product of the sharing of social models, something only humans appear to do. The self of which we are aware is not something innate within us, it is a model of our self produced as a response to the models of us offered to us by other people. Edwardes proposes that human construction of selfhood involves seven different types of self. All but one of them are internally generated models, and the only non-model, the actual self, is completely hidden from conscious awareness. We rely on others to tell us about our self, and even to let us know we are a self. Developed in relation to a range of subject areas – linguistics, anthropology, genomics and cognition, as well as socio-cultural theory – The Origins of Self is of particular interest to MARTIN P. J. EDWARDES students and researchers studying the origins of language, human origins in general, and the cognitive differences between human and other animal psychologies. Martin P. J. Edwardes is a visiting lecturer at King’s College London. He is currently teaching modules on Language Origins and Language Construction. -

Daniel Whistler

Speculations III [email protected] www.speculations-journal.org Editors Michael Austin Paul J. Ennis Fabio Gironi Thomas Gokey Robert Jackson isbn 978-0988234017 Front Cover: unanswered: witness Grace Lutheran Church Parking Lot, Linwell Road, St. Catharines, June 2003 by P. Elaine Sharpe Back Cover: unanswered: witness Flight Simulation Training Center, Opa Locka Airport, FLA, December 2002 by P. Elaine Sharpe Courtesy of P. Elaine Sharpe, used with permission. pesharpe.com The focal distance in these photograph is at the normal range of human conversational distance, 3 meters. Although the image may appear to be out of focus, it is focused on the absence of human presence. Designed by Thomas Gokey v 1.0 punctum books ✴ brooklyn, ny 2012 Editorial Introduction 5 Articles Re-asking the Question of the Gendered Subject after 7 Non-Philosophy Benjamin Norris Thing Called Love 43 That Old, Substantive, Relation Beatrice Marovich The Other Face of God 69 Lacan, Theological Structure, and the Accursed Remainder Levi R. Bryant Improper Names for God 99 Religious Language and the “Spinoza-Effect” Daniel Whistler Namelessness and the Speculative Turn 135 A Response to Whistler Daniel Colucciello Barber Diagonals 150 Truth-Procedures in Derrida and Badiou Christopher Norris Synchronicity and Correlationism 189 Carl Jung as Speculative Realist Michael Haworth Translations Über stellvertretende Verursachung 210 Graham Harman Speculative Realism 241 After finitude, and beyond? Louis Morelle Position Papers and Interview 273 Outward Bound -

Transitions: Fall 2016 Mcgill & the World

TRANSITIONS: 2016 FALL MCGILL & THE WORLD A PUBLICATION OF THE The BULL & BEAR EDITOR’S NOTE CONTENTS Jennifer Yoon Executive Editor FEATURE 4 Holding McGill Accountable 5 Humanities Under Attack 7 Two-Sides of a Coin: The Smoking Ban Shifting sands have never felt more unsettling. NEWS That’s only half a simile. The giant holes tearing up our campus streets are 8 Profile of Trump literally scrambling the soil beneath our feet. Apparently, our helmeted Supporters on Campus brigade of construction workers will be around for at least a few more years. What exactly are they working on again? Nobody knows. 10Indigenous Awareness Week Students are hurting from the myriad of changes, too. We’ve seen protests against austerity measures and for student workers’ rights. With classes BUSINESS & TECH and extracurriculars curtailed, students unsurprisingly take to the streets 11 Make Polling Great Again in protest – fulfilling a longstanding tradition amongst les étudiants 12 The Future of Food Montréalais. 14 Emergence of a Cashless Society And then, of course, there is the political fiasco South of the border. The election brought out the ugly in American society, terrifying women, racial minorities, LGBTQ folks, and more. Others began to seriously question ARTS & CULTURE the inherent value of previously revered democratic institutions: the 17 Crying in the Club with fourth estate, pluralism, and even foundational electoral processes. Venus 19 Skirting the Issues For many of us, 2016 has been a momentous year: in the course of these 21 Obituary: Public Libraries months, we’ve become accustomed a permanent state of uncertainty. (300 BC-2016 AD) 23 I Spend Way Too Much In this issue, we have tried to unpack some aspects of our increasingly unpredictable world – both on-campus, and off-campus. -

The Speculative Turn Continental Materialism and Realism

The Speculative Turn Continental Materialism and Realism Edited by Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek and Graham Harman Open Access Statement – Please Read This book is Open Access. This work is not simply an electronic book; it is the open access version of a work that exists in a number of forms, the traditional printed form being one of them. Copyright Notice This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal aca- demic scholarship without express permission of the author and the publisher of this volume. Furthermore, for any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. For more information see the details of the creative commons licence at this website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ This means that you can: • read and store this document free of charge • distribute it for personal use free of charge • print sections of the work for personal use • read or perform parts of the work in a context where no financial transactions take place However, you cannot: • gain financially from the work in anyway • sell the work or seek monies in relation to the distribution of the work • use the work in any commercial activity of any kind • profit a third party indirectly via use or distribution -

2012 EWDA Conference Program and Abstract Book.Pdf

Contents Welcome Address 5 Conference Program 7 Abstracts Oral Presentations 15 One Health Session 17 Population Health Assessment Session 34 Migration Session 48 WDA Student Research Recognition Award 51 Terry Amundson Award Student Session 52 Disease Control Session 72 Pathogenesis Session 79 Pathogen Discovery and Disease Emergence Session 86 Translocation and Reintroduction Session 89 Multiple Pollutants 92 Poster Presentations 93 Poster Session 1 95 Poster Session 2 217 Poster Session 3 325 Workshops 427 WDA EWDA 2012 Conference Scientific Committee 429 WDA EWDA 2012 Conference Organizing Committee 429 WDA 2012 Officers and Council 430 EWDA 2010/2012 Officers and Board 430 Index of Presenting Authors 433 WDA EWDA 2012: Site of Interest Map 437 Conference Overview 3 4 Welcome Address Dr. Bernard VALLAT, Directeur général de l'Organisation Mondiale de la Santé Animale (OIE), 12 rue de Prony, 75017 Paris The OIE welcomes participants to the “Convergence in wildlife health” Conference and is pleased to have been a partner for this successful event, alongside VetAgro Sup, the WDA and the EWDA. Movements of animals and people enable pathogens to travel faster than the incubation period of the epizootic diseases they cause and the health risks for humans, domestic animals and wildlife are rapidly evolving. Growth of the human population, climate change and increased land use are all factors that must be urgently taken into account to safeguard biodiversity on all continents. The Veterinary Services and veterinary teaching establishments must strengthen their capacities in the field of wildlife conservation and health management. New tools and new forms of collaboration and synergies need to be established between these services, wildlife specialists and users of the natural environment, which will in future provide valuable assistance in this field .