Why Rebels Reject Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

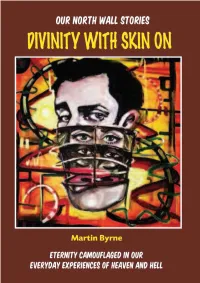

Divinity with Skin On

OUR NORTH WALL STORIES DIVINITY WITH SKIN ON Oct 17 UN Day for the Eradication of Poverty Commemoration at the Human Rights and Poverty Stone. Photo courtesy of ATD Fourth World Martin Byrne Eternity Camouflaged In Our Everyday Experiences Of Heaven and Hell CONTENTS Foreword 4 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 11 Dedication 12 Ciara Lindsay Stopping to Appreciate How Amazing Life Is 14 Melanie McQuade Prehistoric Fish Traps Found In Spencer Dock 17 The Duffy Family Duffy Bookbinders Seville Place 19 Noel Gregory My Dockland Memories 21 John Weafer, Fergus McCabe and NYP2 We Are Humanity 26 Pat Deery and staff 20 North Great Georges Street – 28 An Acorn Was Planted Miriam Weir Mystery Searching for Us in 33 Cherry Orchard and North Wall Joe McDonald, Bill O’Shaughnessy and Patrick Corkery Ronnie McCabe, Dominic Sassi, Phil Ryan, Finian Gavin, David Ryan and Seamus Gil,l Christian Elliot, Calvin Byrne, Creative Musings from the Larriers CBS 42 Noel Ryan and Jake Fay Dúil sna Leabhair, Muintir an Raghnall Cooke tSraidbhaile Seo Againne 49 Gwen Sheils, Anita Maher Poetry – Cherry Orchard Imaginations 52 Seamus Gill, Mary Mooney, Geraldine Griffin, June Howell, Dolores Cox, Geraldine Griffiths, Siobhan Mokrani and Monica Sheppard Laura Larkin The Passion Project – Ballyfermot/Cherry Orchard 67 Leyla Carr Imaginative Expressions from The Girls At St Laurence O Tooles 71 Chloe Lawless, Mia McInerney et al. Damien Murray My Story of Darkness into Light 76 2 Kathleen Cronin Courage to Change 78 Morgan Rafferty One Life Makes a Difference 79 Hugh -

The Irish Volunteers in North Co. Dublin, 1913-17

Title The Irish Volunteers in north Co. Dublin, 1913-17 By Peter Francis Whearity SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MA IN LOCAL HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Supervisor of research: Dr Terence A. Dooley December 2011 Contents Page Illustrations iii Abbreviations iv Acknowledgment v Map 1 specifically made for this study vi Map 2 Ordnance Survey of Ireland, Townland Index, for County Dublin vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The formation of the Irish Volunteer movement 10 Chapter 2 The National Volunteer movement 28 Chapter 3 The Redmondite-split and its aftermath 47 Chapter 4 The 1916 Rising in north County Dublin 68 Chapter 5 The aftermath of the Rising 88 Conclusion 111 Appendix 121 Bibliography 134 List of Tables Table 1 Irish Volunteer companies formed in north County Dublin up to 11 June 1914 27 Table 2 Irish national Volunteer companies formed after 11 June 1914 45 Table 3 National Volunteer companies at the time of the Redmondite-split 58 Table 4 County Dublin Volunteer membership figures for the period beginning July 1914, until Apr. 1916 67 Table 5 Places in north County Dublin from where arrested men came from after the Rising 90 i Table 6 Age profiles of north County Dublin men arrested after the Rising 92 Table 7 Marital status of north County Dublin men arrested after the 1916 Rising 93 Table 8 Occupational profiles of north County Dublin men arrested after the Rising 94 Table 9 Category A prisoners from north County Dublin after the Rising 96 Table 10 Category B prisoners from north County Dublin after the Rising 97 Table 11 Category C prisoners from north County Dublin after the Rising 98 Table 12 Classification of arrested north County Dublin men on R.I.C. -

The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office

1 Irish Capuchin Archives Descriptive List Papers of The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Collection Code: IE/CA/CP A collection of records relating to The Capuchin Annual (1930-77) and The Father Mathew Record later Eirigh (1908-73) published by the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Compiled by Dr. Brian Kirby, MA, PhD. Provincial Archivist July 2019 No portion of this descriptive list may be reproduced without the written consent of the Provincial Archivist, Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, Ireland, Capuchin Friary, Church Street, Dublin 7. 2 Table of Contents Identity Statement.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Context................................................................................................................................................................ 5 History ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Archival History ................................................................................................................................. 8 Content and Structure ................................................................................................................................... 8 Scope and content ............................................................................................................................. 8 System of arrangement .................................................................................................................... -

A History of Force Feeding

A History of Force Feeding Ian Miller A History of Force Feeding Hunger Strikes, Prisons and Medical Ethics, 1909–1974 This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material. Ian Miller Ulster University Coleraine , United Kingdom ISBN 978-3-319-31112-8 ISBN 978-3-319-31113-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-31113-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016941754 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 Open Access This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Papers of John Hagan, Irish College Rome (1904-1930)

Archival list Papers of John Hagan, Irish College Rome (1904-1930) ARCHIVES PONTIFICAL IRISH COLLEGE, ROME Papers of John Hagan, Irish College Rome (1904-1930) COLLECTION IDENTITY STATEMENT Title: Papers of Rector John Hagan, Irish College Rome Covering Dates: 1904-1930 Collection Codes: PICR Archives HAG 1/- HAG 6/ Collection Size: 24 boxes Finding Aids: Descriptive list Description level: item Table of contents Introduction i-xiv CORRESPONDENCE 1904-1930 (HAG 1/) by year 1904 1 1905 2 1906 14 1907 24 1908 35 1909 46 1910 66 1911 95 1912 138 1913 184 1914 239 1915 291 1916 333 1917 369 1918 399 1919 433 1920 613 1921 743 1922 948 1923 1136 1924 1327 1925 1500 Table of contents (continued) (Correspondence 1904-1930 HAG1/ continued) 1926 1673 1927 1834 1928 2021 1929 2176 1930 2300 Undated correspondence A-Z (HAG2/) 2312 Political papers and newsprint (HAG 3/) 2345 Publications- drafts, notes, print items (HAG4/) 2373 Historical research and draft articles (HAG5/) 2381 Homiletical/ liturgical papers (HAG6/) 2385 Appendix 1) Hagan 'private' papers 2404 Papers of John Hagan, Irish College Rome (1904-1930) INTRODUCTION The collection of the papers of Rector Mgr John Hagan at the Pontifical Irish College, Rome, contains for the most part incoming mail deriving from his vice-rectorship (1904-1919) and rectorship (1919-1930) up to his death in March 1930. The subseries further illustrate his keen interest in both contemporary Irish and Italian politics and in academic history – treated often in his commentary as a counterfoil for contemporary Irish society -, as well as his priestly office. -

Catalogue 144

De Búrca Ra re Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 144 Winter 2021 i DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin, A94 V406 01 288 2159 / 01 2886960 CATALOGUE 144 Winter 2021 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Watson is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 144: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly with order for books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. Items may be collected. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We will be open to visitors when restrictions are lifted. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring single items or collections, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa, Mastercard, PayPal, Cheque and Bank Transfer. 12. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 13. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin, A94 V406. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Mobile (087) 2595918. International + 353 87 2595918 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front cover illustration is taken from item 304 the rare Watson Lithograph. -

Military Landscapes

1248 First World War Military Sites Military Landscapes Part 1: Report and Gazetteer Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd Gwynedd Archaeological Trust First World War Military Sites Military Landscapes Part 1: Report and Gazetteer Project No. G2180 Report No. 1248 Prepared for: Cadw March 2015, corrections May 2015 Written by: Jane Kenney and David Hopewell (with a contribution by Robert Johnston) Illustration by: Jane Kenney, David Hopewell and Neil McGuinness Cover photograph: Postcard of Camp at Conwy Morfa 1914, with Deganwy camp in background (postcard, owned by R Evans) Cyhoeddwyd gan Ymddiriedolaeth Achaeolegol Gwynedd Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd Craig Beuno, Ffordd y Garth, Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2RT Published by Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Craig Beuno, Garth Road, Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2RT Cadeiryddes/Chair - Yr Athro/Professor Nancy Edwards, B.A., PhD, F.S.A. Prif Archaeolegydd/Chief Archaeologist - Andrew Davidson, B.A., M.I.F.A. Mae Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd yn Gwmni Cyfyngedig (Ref Cof. 1180515) ac yn Elusen (Rhif Cof. 508849) Gwynedd Archaeological Trust is both a Limited Company (Reg No. 1180515) and a Charity (reg No. 508849) FIRST WORLD WAR MILITARY SITES: MILITARY LANDSCAPES GAT PROJECT NO. G2180 GAT REPORT NO. 1248 Part 1: Report and Gazetteer Contents Summary................................................................................................................................................................. 4 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ -

The Coming of the Celts, AD 1862

The Coming of the Celts, AD 1860 The Coming of the Celts, AD 1860 Celtic Nationalism N in Ireland and Wales Caoimhín De Barra University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 undpress.nd.edu Copyright © 2018 by University of Notre Dame All Rights Reserved Published in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: De Barra, Caoimhín, 1984– author. Title: The coming of the Celts, AD 1860 : Celtic nationalism in Ireland and Wales / Caoimhín De Barra. Other titles: Celtic nationalism in Ireland and Wales Description: Notre Dame, Indiana : University of Notre Dame Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2017055845 (print) | LCCN 2018007086 (ebook) | ISBN 9780268103392 (pdf ) | ISBN 9780268103408 (epub) | ISBN 9780268103378 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 0268103372 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Celts—Politics and government. | Celts—Ethnic identity. | Nationalism—Ireland. | Nationalism—Wales. | Civilization, Celtic. Classification: LCC DA42 (ebook) | LCC DA42.D47 2018 (print) | DDC 320.540941509/034—dc23 ∞ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at [email protected] Le Kathy agus Aisling, mo mhná maoiní CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 The Coming of -

They Dreamed and Are Dead Limerick 1916

1916 Cover 6 page.qxp_Layout 1 02/03/2016 17:59 Page 1 Too long a sacrifice Can make a stone of the heart O when may it suffice? That is Heaven's part, our part they dreamed and are dead - Limerick 1916 To murmer name upon name, As a mother names her child When sleep at last has come On limbs that had run wild. What is it but nightfall? No, no, not night but death; Was it needless death after all? For England may keep faith For all that is done and said. We know their dream; enough To know they dreamed and are dead; And what if excess of love Bewildered them till they died? I write it out in a verse- MacDonagh and MacBride And Connolly and Pearse Now and in time to be, Wherever green is worn, they dreamed and are dead Are changed, changed utterly: A terrible beauty is born. W B Yeats Limerick 1916 Easter 1916 ISBN: 978-0-905700-24-3 John J Quilty and his wife Madge in the Brisco car, used by the By Dr Matthew Potter | William O’Neill | Brian Hodkinson | Edited by Jacqui Hayes 1 Volunteers for the ill-fated trip to Kerry to meet Roger Casement and the Aud. (Courtesy Joe Quilty) 1 1916 Cover 6 page.qxp_Layout 1 02/03/2016 17:59 Page 2 We know their dream; enough to know they dreamed and are dead William Butler Yeats Copyright Information: Authors: Design and Print: Published by Limerick City and County Council Dr. Matthew Potter, Historian, Limerick Archives AViD Graphic Design, Limerick © Limerick City and County Council William O’ Neill, Scholar Limerick Museum and The Daly family as returned in the 1901 census. -

Michael Collins: Little Fellow, Big Fellow

1 MICHAEL COLLINS: LITTLE FELLOW, BIG FELLOW Psychologists have often debated the concept of the charismatic leader, whet her he or she becomes so by nature or nurture. Like most true talents, charisma must surely be innate, honed and improved by the learning process and experience, but a true gift of nature nonetheless. There was one man who changed the course of Irish history, thrice blessed, not only charismatic, but also handsome and possessing a larger-than-life personality. He had a winning smile, warm personality, charmed women and inspired men; some one who in any walk of life would have been a success, earning him the popu lar title by which he was, for ever after, referred to by his followers and admirers. This was ‘The Big Fellow’, and that man was Michael Collins. T!" L#$$%" F"%%&' The ‘Big Fellow’ was once a ‘Little Fellow’, born in the early hours of the morning of Thursday 16 October 1890 at Wood- field, a small farm nestling in the hills of West Cork, about three miles from Clonakilty. The land had been in the Collins family for seven generations. Michael was the youngest of eight 23 MICHAEL COLLINS HIMSELF children, three boys and five girls, born to Michael Collins, a farmer, and his young wife Marianne (née O’Brien), nearly forty years his junior. Michael’s father was sixty years old in 1876 when he finally married Mari anne, his fatherless goddaughter, who lived with her brothers, sisters and elderly mother at a farm in Sam’s Cross, a small hamlet about half a mile down the lane way from Woodfield. -

CATALOGUE 16 Autumn 2016

Healy Rare Books CATALOGUE 16 Autumn 2016 1 2 Healy Rare Books Catalogue Sixteen Tel. Number: +353(0)91 529980 “Meadowlands” E-Mail: [email protected] Lioscarraig Website: www.healyrarebooks.com Threadneedle Road Galway Ireland Dear Bibliophile/Collector, Catalogue sixteen enclosed with its customary mix of rare, unusual and desirable items. This current year is remarkable for the many historical anniversaries of seismic events that shaped the future growth of our country particularly the Easter Rising in 1916 and the subsequent executions of their heroic leaders, most of whom were poets, teachers, academics and humanitarians such as Casement and Sheehy-Skeffington. All are represented within these covers. 2016 also marks the 150th anniversary of the laying of the atlantic cable between Newfoundland and Valentia. There are also some outstanding bindings of the works of Swift, Hall, Bartlett, Cromwell, Moore and Boyle. Renewed thanks for your continuing & loyal support. Norman Healy 3 Abbreviations Color Colour Color Color Ex. Cat. Exhibition Catalogue A.E.G. All edges gilt T.E.G. Top edge gilt B.P. Book plate Cl. Calf Cntp. Contemporary Décor Decorative D.J. Dust Jacket First First Edition 8vo Octavo 4to Quarto O.U.P. Oxford University Press U.P. University Press Wraps Wrappers C.P. Cuala Press Ltd Edit. Limited Edition R.H.A. Royal Hibernian Academy Kindly Note – Private Premises. Sale by Catalogue only. Payment on receipt of books and any item found unsatisfactory may be returned within 7 days. Prices are net and in Euro. All major currencies welcome and not liable to conversion charges. Postage, packaging and insurance are extra. -

Miami Vice Edited by Jacob O'rourke, David Dennis, Mike

WHAQ (Washington High Academic Questionfest) III: Miami Vice Edited by Jacob O’Rourke, David Dennis, Mike Etzkorn, Bradley McLain, Ashwin Ramaswami and Chandler West Written by current and former members of the teams at Washington and Miami Valley; Aleija Rodriguez; Ganon Evans, and Max Shatan Packet 1 Tossups 1. A speaker in one of this man’s poems wishes to “sleep the sleep of apples,” and in a poem about a sleepwalker, the speaker desires the color green. In another poem by this author of “Gacela of the Dark Death,” the speaker repeatedly refuses to see the corpse of Ignacio, who died (*) “at five in the afternoon.” In a play by this author, Leonardo Felix is chased down by “the Father” and “the Groom” for running away with “the Bride.” For 10 points, name this Spanish author of “Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter” and Blood Wedding. ANSWER: Federico García Lorca <European/World Lit> <Carrie Derner>/<ed. ME> 2. One future leader of this country occupied Boland’s Mill during a revolutionary uprising, and, despite being sentenced to death for that action, was spared due to his American birth. Another revolutionary leader in this country organized protests at Frongoch Internment Camp, and also organized an assassination attempt on the Cairo Gang that became known as Bloody (*) Sunday. Eamon [“Ay-mon”] de Valera and Michael Collins were both members of this country’s Sinn Fein [“shin fain”] party, and both men participated in this country’s 1916 Easter Rising. For 10 points, name this country with capital at Dublin. ANSWER: Ireland [or Republic of Ireland; or Éire; do NOT accept or prompt on “Northern Ireland”] <European History> <Tyler Benedict>/ed.