No Man's Wishes Are Stronger Than Witches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Ken Clarke

KEN CLARKE - MY PROFESSIONAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY When I left junior school at the age of twelve my plastering career started at the well known building Arts & Craft Secondary School, ‘Christopher Wren’, and from this early age I was particularly interested in fibrous plastering. It was a known fact that, of a class of 16, two of the pupils, after four years of schooling, would start their training at a major film studio. I passed my GCE in Building Craft, Paintwork and Plasterwork (copy 1 attached) and was one of the lucky two to be chosen to start training at Shepperton Studios. This was my first achievement (copy 2 – letter of engagement, 9 June 1964, attached). I started Shepperton Studios in the plastering Dept on 22 June 1964 under conditions of a six-month probationary period and a further 4 and half years. During this five-year apprenticeship, I was to do through the block release system, eight weeks at work and two weeks at Art & Craft College ‘Lime Grove’. At the end of five years I was awarded my basic and final City and Guilds in plastering (basic June 1966 and final June 1968 – copies 3 and 4 attached). This was a big achievement for any young man – for me; it was the beginning of a big career. After my five years I was presented with one of the very last certificates of apprenticeship offered by the ‘Film Industry Training Apprenticeship Council’. Thus, my apprenticeship came to an end. (Letter of thanks and delivery of my deeds and certificate 1 June 1969. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

Shak Shakespeare Shakespeare

Friday 14, 6:00pm ROMEO Y JULIETA ’64 / Ramón F. Suárez (30’) Cuba, 1964 / Documentary. Black-and- White. Filming of fragments of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet staged by the renowned Czechoslovak theatre director Otomar Kreycha. HAMLET / Laurence Olivier (135’) U.K., 1948 / Spanish subtitles / Laurence Olivier, Eileen Herlie, Basil Sydney, Felix Aylmer, Jean Simmons. Black-and-White. Magnificent adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy, directed by and starring Olivier. Saturday 15, 6:00pm OTHELLO / The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice / Orson Welles (92’) Italy-Morocco, 1951 / Spanish subtitles / Orson Welles, Michéal MacLiammóir, Suzanne Cloutier, Robert Coote, Michael Laurence, Joseph Cotten, Joan Fontaine. Black- and-White. Filmed in Morocco between the years 1949 and 1952. Sunday 16, 6:00pm ROMEO AND JULIET / Franco Zeffirelli (135’) Italy-U.K., 1968 / Spanish subtitles / Leonard Whiting, Olivia Hussey, Michael York, John McEnery, Pat Heywood, Robert Stephens. Thursday 20, 6:00pm MACBETH / The Tragedy of Macbeth / Roman Polanski (140’) U.K.-U.S., 1971 / Spanish subtitles / Jon Finch, Francesca Annis, Martin Shaw, Nicholas Selby, John Stride, Stephan Chase. Colour. This version of Shakespeare’s key play is co-scripted by Kenneth Tynan and director Polanski. Friday 21, 6:00pm KING LEAR / Korol Lir / Grigori Kozintsev (130’) USSR, 1970 / Spanish subtitles / Yuri Yarvet, Elsa Radzin, GalinaVolchek, Valentina Shendrikova. Black-and-White. Saturday 22, 6:00pm CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT / Orson Welles (115’) Spain-Switzerland, 1965 / in Spanish / Orson Welles, Keith Baxter, John Gielgud, Jeanne Moreau, Margaret 400 YEARS ON, Rutherford, Norman Rodway, Marina Vlady, Walter Chiari, Michael Aldridge, Fernando Rey. Black-and-White. Sunday 23, 6:00pm PROSPERO’S BOOKS / Peter Greenaway (129’) U.K.-Netherlands-France, 1991 / Spanish subtitles / John Gielgud, Michael Clark, Michel Blanc, Erland Josephson, Isabelle SHAKESPEARE Pasco. -

Notable Film Adaptions

Notable Film adaptions from Shakespeare's work shakespearecandle.com The following are the most notable film adaptations based on Shakespeare's plays. Some of the complete films can be played on shakespearecandle for free. The Taming of the Shrew, (1929), starring Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. Directed by Sam Taylor. A Midsummer Night's Dream, (1935), starring James Cagney, Dick Powell, Ian Hunter. Directed by Max Reinhardt and William Dieterle. Romeo and Juliet, (1936), starring Leslie Howard and John Barrymore. Directed by George Cukor. As You Like It, (1936), starring Henry Ainley and Elisabeth Bergner. Directed by Paul Czinner. Henry V, (1944), starring Laurence Olivier, Robert Newton, Leslie Banks. Directed by Lawrence Olivier. Macbeth, (1948), starring Orson Welles, Jeanette Nolan, Dan O'Herlihy. Directed by Orson Welles. ** Hamlet, (1948), starring Laurence Olivier, Jean Simmons, John Laurie. Directed. by Lawrence Olivier. Othello, (1952), starring Orson Welles, Micheál MacLiammóir, Robert Coote. Directed by Orson Welles. Julius Caesar, (1953), starring Marlon Brando, Louis Calhern, James Mason. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Romeo and Juliet, (1954), starring Laurence Harvey, Susan Shentall, Flora Robson. Directed by Renato Castellani. Richard III, (1955), starring Laurence Olivier, Cedric Hardwicke, Nicholas Hannen. Directed by Lawrence Olivier. Othello, (1955), starring Sergey Bondarchuk, Irina Skobtseva, Andrei Popov. Directed by Sergei Jutkevitsh. Forbidden Planet, (1956) starring Walter Pidgeon, Anne Francis, Leslie Nielsen Directed by Fred M. Wilcox. (Based on The Tempest.) Throne of Blood / The Castle of the Spider's Web / Cobweb Castle, (1957), starring Toshiro Mifune, Isuzu Yamada, Minoru Chiaki. Directed by Akira Kurosawa. (Transposes the plot of Macbeth to feudal Japan.) The Tempest, (1960), (TV) starring Richard Burton. -

Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96;

. MC0111117 VESUI17 Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96; AUTHOR McLean, Ardrew M. TITLE . ,A,Shakespeare: Annotated BibliographiesendAeaiaGuide 1 47 for Teachers. .. INSTIT.UTION. NIttional Council of T.eachers of English, Urbana, ..Ill. .PUB DATE- 80 , NOTE. 282p. AVAILABLe FROM Nationkl Coun dil of Teachers,of Englishc 1111 anyon pa., Urbana, II 61.801 (Stock No. 43776, $8.50 member, . , $9.50 nor-memberl' , EDRS PRICE i MF011PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Biblioal7aphies: *Audiovisual Aids;'*Dramt; +English Irstruction: Higher Education; 4 *InstrUctioiral Materials: Literary Criticism; Literature: SecondaryPd uc a t i on . IDENTIFIERS *Shakespeare (Williaml 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this annotated b'iblibigraphy,is to identify. resou'rces fjor the variety of approaches tliat teachers of courses in Shakespeare might use. Entries in the first part of the book lear with teaching Shakespeare. in secondary schools and in college, teaching Shakespeare as- ..nerf crmance,- and teaching , Shakespeare with other authora. Entries in the second part deal with criticism of Shakespearear films. Discussions of the filming of Shakespeare and of teachi1g Shakespeare on, film are followed by discu'ssions 'of 26 fgature films and the,n by entries dealing with Shakespearean perforrances on televiqion: The third 'pax't of the book constituAsa glade to avAilable media resources for tlip classroom. Ittries are arranged in three categories: Shakespeare's life'and' iimes, Shakespeare's theater, and Shakespeare 's plam. Each category, lists film strips, films, audi o-ca ssette tapes, and transparencies. The.geteral format of these entries gives the title, .number of parts, .grade level, number of frames .nr running time; whether color or bie ack and white, producer, year' of .prOduction, distributor, ut,itles of parts',4brief description of cOntent, and reviews.A direCtory of producers, distributors, ard rental sources is .alst provided in the 10 book.(FL)- 4 to P . -

Pericles, Prince of Tyre Edited by Doreen Delvecchio and Antony Hammond Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-29710-3 - Pericles, Prince of Tyre Edited by Doreen Delvecchio and Antony Hammond Frontmatter More information THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE general editor Brian Gibbons associate general editor A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. From 1990 to 1994 the General Editor was Brian Gibbons and the Associate General Editors were A. R. Braunmuller and Robin Hood. PERICLES, PRINCE OF TYRE Over the last two decades there has been a resurgence of theatrical interest in Shakespeare’s Pericles, which has been rescued from comparative neglect and is now frequently performed. This development is charted in the Introduction to this edition, which differs radically from any other currently available. Doreen DelVecchio and Antony Hammond reject the current ortho- doxies: that the text is seriously corrupt and that the play is of divided authorship. They show how the 1609 quarto has features in common with the first quarto of King Lear,nowwidely regarded as being based on Shakespeare’s manuscript. Likewise they regard the arguments concerning divided authorship as unproven and misleading. Instead they show the play to be a unified aesthetic experience. The result is a view of Pericles far more enthusiastic than that of other editors. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University -

The • Vpstart • Cr.Ow

Vol. XV THE • VPSTART • CR.OW Editor James Andreas Clemson University Founding Editor William Bennett The University of Tennessee at Martin Associate Editors Michael Cohen Murray State University Herbert Coursen Bowdoin College Charles Frey The University of Washington Marjorie Garber Harvard University Walter Haden The University of Tennessee at Martin Maurice Hunt Baylor University Richard Levin The University of California, Davis John McDaniel Middle Tennessee State University Peter Pauls The University of Winnipeg Jeanne Roberts American University Production Editors Tharon Howard and Irfan Tak Clemson University Editorial Assistants Kim Bell, Laurie Brown, Pearl Parker, Judy Payne, Heather Pecoraro, and Jeannie Sullivan Copyright 1995 Clemson University All Rights Reserved Clemson University Digital Press Digital Facsimile Vol. XV About anyone so great as Shakespeare, it is probable that we can never be right, it is better that we should from time to time change our way of being wrong. - T. S. Eliot What we have to do is to be forever curiously testing new opinions and courting new impressions. -Walter Pater The problems (of the arts) are always indefinite, the results are always debatable, and the final approval always uncertain. -Paul Valery Essays chosen for publication do not necessarily represent opin ions of the editor, associate editors, or schools with which any contributor is associated. The published essays represent a diver sity of approaches and opinions which we hope will stimulate interest and further scholarship. Subscription Information Two issues- $12 Institutions and Libraries, same rate as individuals- $12 two issues Submission of Manuscripts Essays submitted for publication should not exceed fifteen to twenty double spaced typed pages, including notes. -

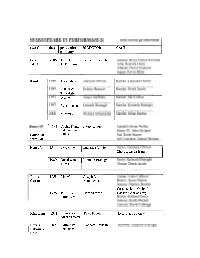

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

View Publication

Vol. XIX THE • VP.START • CROW• Editor J ames Andreas Clemso11 U11iversity Fou11di11g Editor William Bennett The University of Tennessee at Martin Associate Editors Michael Cohen Murray State U11iversity Herbert Coursen University of Maine, Augusta Charles Frey The U11 iversity of Washington Marjorie Garber Harvard U11iversity Juana Green Clemson University Walter Haden The U11 iversity of Tennessee at Marti11 Chris Hassel Va11derbilt University Maurice Hunt Baylor U11iversity Richard Levin The U11iversity of California, Davis John McDaniel Middle Te11nessee State University Peter Pauls The Un iversity of Wimzipeg Jeanne Roberts America11 U11 iversity Business Managers Martha Andreas and Charlotte Holt Clemson U11iversity Productio11 Editors Tharon Howard, William Wentworth, and Allen Swords Clemson University Account Managers Pearl Parker and Judy Payne Copyright 1999 Clemson University All Rights Reserved Clemson University Digital Press Digital Facsimile Vol. XIX About anyone so great as Shakespeare, it is probable that we can never be right, it is better that we should from time to time change our way of being wrong. -T. S. Eliot What we have to do is to be forever curiously testing new opinions and courting new impressions. -Walter Pater The problems (of the arts) are always indefinite, the results are always debatable, and the final approval always uncertain. -Paul Valery Essays chosen for publication do not necessarily represent opinions of the editor, associate editors, or schools with which any contributor is associated. The published essays represent a diversity of approaches and opinions which we hope will stimulate interest and inspire new scholarship. Subscription Information Two issues-$14 Institutions and Libraries, same rate as individuals-$14 two issues Submission of Manuscripts Essays submitted for publication should not exceed fifteen to twenty double spaced typed pages, including notes. -

The Genius of Hitchcock Part One: August 2012

12/44 The Genius of Hitchcock Part One: August 2012 Special events include: x Tippi Hedren in Conversation x TV Preview + Q&A: THE GIRL – new BBC2 drama telling the full story of Hitchcock’s relationship with Tippi Hedren x Camille Paglia: Women & Magic in Hitchcock x The Lodger + composer Nitin Sawhney in Conversation Over the course of almost three months, Hitchcock’s surviving body of work as director will be presented in its entirety at BFI Southbank. The films will be grouped together, taking inspiration from one his most famous films to present the 39 Steps to the Genius of Hitchcock to help audiences increase their understanding of this complex and fascinating director. The first part of the BFI Southbank season in August, with special thanks to Sky Movies/HD, focuses on the first 12 steps, beginning with The Shaping of Alfred Hitchcock. The recent discovery in New Zealand of several reels of The White Shadow, scripted by Hitchcock, made international headlines. But other material, too, survives from his apprentice years, prior to The Pleasure Garden. In The Shaping of Hitchcock: Reflections on The White Shadow author Charles Barr will present a richly illustrated narrative of Hitchcock’s formative years, as an introduction to a screening of the thus-far incomplete The White Shadow (1924). BFI Future Film presents The DIY Thriller Film Fortnight to accompany the second step: The Master of Suspense. This course will give participants aged 15-25 the chance to make short thriller films inspired by Hitchcock. The Evolution of Style will look at the development of Hitchcock’s style – described by the director as ‘the first true Hitchcock film’, The Lodger (1926) introduces themes that would run through much of Hitchcock’s later work.