REGIONAL LABOR REVIEW of the New York Metropolitan Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean's Annual Report

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean’s Annual Report Fiscal Year 2011 Harvard University 1 Table of Contents Harvard College ........................................................................................................................... 9 Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) ......................................................................... 23 Division of Arts and Humanities ................................................................................................ 29 Division of Science .................................................................................................................... 34 Division of Social Science ......................................................................................................... 38 School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) ............................................................... 42 Faculty Trends ............................................................................................................................ 49 Harvard College Library ............................................................................................................ 54 Sustainability Report Card ......................................................................................................... 59 Financial Report ......................................................................................................................... 62 2 Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Office of the Dean University Hall Cambridge, Massachusetts -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Note to User

NOTE TO USER Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. This is reproduction is the best copy available THE NUTRIENT AND PHYTONUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF ONTARIO GROWBEANS AND =IR EFFECT ON AZOXYMETHANE INDUCED COLONTC PRENEOPLASIA IN RATS Heten Anita MiUie Samek A thesis submitted in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Graduate Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto Copyright by Helen Anita Millie Samek 200 1 Acquisitions and Acquisit'hs et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliiraphiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aliowhg the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to BkIiothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auîeur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenivise de ceile-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. TEE NUTRIENT AND PaYTONUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF ONTARIO GROWN BEANS AND THEIR EFFECT ON AZOXYMETHANE INDUCED COLONIC PRENEOPLASIA IN RATS Master of Science, 200 1 Helen A. Samek Graduate Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto Beans have long been recognized for their nutritionai quality. -

Retrospect Magazine Design Layout.Indd

2000 HELLO HELLO MMILLENNIUMILLENNIUM 1999 CCELEBRATIONSELEBRATIONS GOODBYE GOODBYE A lot of people approached the end of 1999 with trepi- dation. There were reports that aeroplanes would fall out of the sky at the stroke of midnight. All computers would crash, leading to world turmoil and people would wake up to a world EXAMPLE IMAGE NOT COPYRIGHT that they did not recognise. CLEARED By Sharon RM Stevens n acknowledgement of this huge mile- Istone in the World’s calendar, most countries and or cities decided to meet the momentous occasion in various ways. Some planned fixed structures to celebrate, while others met the New Year by changing Brighton millennium celebration, image from the Zap archive names of buildings, cities etc. Still, others EXAMPLE IMAGE planned firework displays beyond anything NOT COPYRIGHT anyone had ever CLEARED seen. In an attempt to capture events Tower el ff at the turn of the century, led by the BBC and WGBH-TV and several other EXAMPLE IMAGE companies, the NOT COPYRIGHT CLEARED 2000 Today pro- gramme was cre- Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip at the opening of the Millennium Dome Fireworks burst from the Ei ated. It was to be a way of encapsulating the worldwide New the New year. Samoa being the last. Year events over a 28hour period, starting However, it was later controversially from 31st of December 1999 to the 1st of reported that the first country to cele- January 2000. The TV coverage of New brate the dawning of 2000 was, in fact, Year celebrations would span across sev- the Chatham Islands, New Zealand. -

2020-2021 Master Calendar

MASTER CALENDAR of Nassau County’s 56 School Districts www.nassauboces.org SEPTEMBER Children’s Readiness Center’s George Farber Outstanding Student Award Winner 2020 Carman Road School’s George Farber Outstanding Student Award Winner SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SCHOOL DISTRICT KEY 1 Baldwin UFSD 1 2 3 4 5 2 Bellmore UFSD 3 Bellmore-Merrick CHSD Nassau BOCES Nassau BOCES Nassau BOCES Nassau BOCES Superintendent’s Conference Superintendent’s Conference Superintendent’s Conference Superintendent’s Conference 4 Bethpage UFSD Day* Day* Day* Day* 5 Carle Place UFSD First day of school 13, 16, First day of school 12, 14, First day of school 1, 6, 7, 8, 13, 55 6 East Meadow UFSD 40, 45 18, 23, 25, 39, 41, 42, 49, 10, 17, 19, 24, 31, 56 50, 51, 52, 53, 55 7 East Rockaway UFSD Barry Tech and GC Tech, Nassau BOCES Board 8 East Williston UFSD New Student Orientation, ESL classes begin, Elmont meeting, 7 p.m. 6 p.m. Library, 10 a.m. 9 Elmont UFSD Barry Tech and GC Tech, ESL classes begin, Freeport New Student Orientation, 10 Farmingdale UFSD Library, 10 a.m. 12:45 p.m. 11 Floral Park-Bellerose UFSD 12 Franklin Square UFSD 13 Freeport UFSD 14 Garden City UFSD 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 15 Glen Cove City SD 16 Great Neck UFSD Labor Day International First day of school 20, 27 Patriot Day Literacy Day 17 Hempstead UFSD All schools closed First day of school 18 Herricks UFSD Nassau BOCES offices closed Nassau BOCES 19 Hewlett-Woodmere UFSD First day of school 2, 3, 4, 20 Hicksville UFSD 5, 9, 11, 15, 21, 22, 26, 21 Island Park UFSD 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 43, 44, 46, 47, 22 Island Trees UFSD 48, 54 23 Jericho UFSD First Day of Classes, Dodd 24 Lawrence UFSD Middle School, Freeport, 6 p.m. -

The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of the Long Island Rail Road Main Line Third Track

The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of the Long Island Rail Road Main Line Third Track Prepared for the Long Island Index by HR&A Advisors, Inc. and Parsons Brinckerhoff April 10, 2014 Transportation Investment and the Future of Long Island 3 The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of Third Track on Long Island 20 Transportation Investment and the Future of Long Island HR&A Advisors, Inc. The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of LIRR Third Track | 3 The Long Island Index commissioned HR&A Advisors, Inc. and Parsons Brinkerhoff to study the economic and fiscal impacts of the Third Track project. HR&A Advisors, Inc. (“HR&A”) is a leading economic development consulting firm that specializes in conducting economic and fiscal impact studies on behalf of clients in the public and private sectors. HR&A has measured the economic and fiscal impacts of a diverse array of projects, places, and policies, including Access to the Region’s Core (ARC), the extension of LIRR to Lower Manhattan, The High Line, Times Square, and the New York State Film Production Credit. Parsons Brinkerhoff, Inc. (“PB”) is a global planning and engineering firm with a leading practice in transportation forecasting, nationally and in the New York metropolitan region. PB developed the original 28-county regional Best Practices Model for the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council, and has performed all updates of the model, and has applied it for numerous travel forecasting studies in the region, including those for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. HR&A Advisors, Inc. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

06 Session5.Pdf

The 1st World Humanities Forum Proceedings Session 5 Organizers’ Parallel Session A. UNESCO: Towards a New Humanism B. MEST/NRF: Renaissance of Humanities in Korea C. Busan Metropolitan City: Humanities for Locality The 1st World Humanities Forum Proceedings Organizers’ Parallel Session A. UNESCO: Towards a New Humanism 1. Age of Abundance / Alphonso Lingis (Pennsylvania State University) 2. Subjectivity and Solidarity – a Rebirth of Humanism / In Suk Cha (Seoul National University) 3. Reconstructing Humanism / John Crowley (UNESCO) 4. Transversality, Ecopiety, and the Future of Humanity / Hwa Yol Jung (Moravian College) Session 5 Session The Age of Abundance Alphonso Lingis Pennsylvania State University What immense and growing abundance of commodities we see about us, the result of extraordinary technological advances in industry driven by information and communications technologies! Manufacture has acquired new and advanced materials, and daily contrives new inventions and devises new products. Biotechnology is increasing food production with genetically altered plants and animals, and soon, meat not taken from butchered animals but grown from stem cells. Production is no longer bounded by the limitations of human labor; electrical and nuclear energy power the machines and robots shape materials and assemble cars, jet airplanes, computers, and soon everything. Nanotechnology is beginning to assemble molecules atom by atom, on the way to manufacture computer circuitry out of sand, gold out of lead, even living cells out of atoms. We see ourselves beginning an essentially new kind of human existence, acquiring a new nature— postevolutionary, transhuman. We are awed, fascinated, but also bewildered by the prospect with an abundance beyond all our needs and desires; how shall we deal with it? We are watching extraordinary advances in biotechnology, which promise not only to cure and prevent diseases and correct defects, but, with pharmaceuticals, gene therapy and nanotechnology, to endow our bodies and our minds with greater and also new capacities. -

Central American Immigrant Women's Perceptions of Adult Learning: a Qualitative Inquiry Ana Guisela Chupina Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2004 Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: a qualitative inquiry Ana Guisela Chupina Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chupina, Ana Guisela, "Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: a qualitative inquiry " (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 933. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/933 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: A qualitative inquiry by Ana Guisela Chupina A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Education (Adult Education) Program of Study Committee: Nancy J. Evans, Major Professor Jackie M. Blount Deborah W. Kilgore Carlie C. Tartakov Michael B. Whiteford Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 Copyright © Ana Guisela Chupina, 2004. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3145633 Copyright 2004 by Chupina, Ana Guisela All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

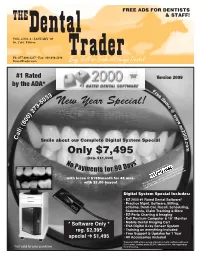

New Year Special! 3 O 7 @ 2 ) W 0 W 0 W 8

FREE ADS FOR DENTISTS THE & STAFF! VOL. 6 NO. Dental1 • JANUARY ‘09 So. Calif. Edition Ph: 877-888-4237 • Fax: 949-498-1198 DentalTrader.com TraderBuy, Sell or Trade all things Dental #1 Rated Version 2009 by the ADA* Fr ee 3 d 3 e 0 m -5 New Year Special! 3 o 7 @ 2 ) w 0 w 0 w 8 . ( e z : l 2 l 0 a 0 9 C . Smile about our Complete Digital System Special c o Only $7,495 m (reg. $11,000) No s* Paym 0 Day ents for 9 Lease provided by with lease @ $198/month for 48 mos. with $1.00 buyout “Financial Solutions for Growing Businesses” for other lease options: contact Erik Mohler @877-692-8156 or [email protected] Digital System Special Includes: • EZ 2000 #1 Rated Dental Software* • Practice Mgmt. Software, Billing, eClaims, Denti-Cal, Recall, Scheduling, Statements, Claim Tracking & More • EZ-Perio Charting & Imaging • Dell Pentium Computer & 19” Monitor • Mobile Dental Imaging Cart * Software Only * • EVA Digital X-ray Sensor System reg. $2,395 • Training on everything included • Free Support & Updates for 1 Year special ‘ $1,495 • All Accessories included *based on ADA online survey of practice mgmt. software with over 5,000 users, costing under $2,500; $99 lease doc. fee required up *not valid for prior purchase front if leasing. 2 SO. CALIFORNIA JANUARY 2009 Business Transactions WOOD & DELGADO Transition Consulting Attorneys At Law Practice Purchase Agreements Partnership Agreements Shareholder Agreements The Authority Associate Agreements Associate Buy-ins in Dental Law MSO's Lease Negotiations Loan Workouts Space Sharing/Group Solo Corporate Formations/Dissolutions Real Estate Acquisition/Sale Employee/Employment Handbooks Dental Board Defense Estate Planning Wills Trusts Power of Attorney Living Will Asset Protection Planning Offices in Irvine, San Francisco & Temecula Patrick J. -

Bios Co Hosts.Indd

Linda Armyn Co Host 2017 LIVE UNITED Celebration Luncheon Linda Armyn is Senior Vice President of Corporate Affairs at Bethpage Federal Credit Union, where she began her tenure in 2001. In her current role she leads Corporate Communications, Public Relations, Business Development, New Market Expansion, Community Development and Government Relations. With a focus on collaboration and innovation, Linda has developed some of Bethpage’s most popular community outreach initiatives and branding campaigns, including the noted “Heart of Bethpage” program. This successful philanthropic effort invests more than $2 million annually to communities of modest means. Another example of a Bethpage program developed under Linda’s leadership that has had tremendous impact is Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA), which has seen Bethpage volunteers prepare nearly $15 million in returns for low income Long Islanders since 2003. Linda is active professionally within her industry and is a member of the Credit Union National Association (CUNA) and the National Association of Federal Credit Unions (NAFCU) legislative committees. On Long Island, she serves as Board Chair of YMCA LI and Mentor New York. She serves as a board member for the Cradle of Aviation, Child Care Council of Suffolk and The Long Island Association. In 2014 she was appointed a member of the Stony Brook University Presidents Council and in 2016, was appointed to the NY Regional Economic Development Council for Long Island. In March of 2015, Linda and Bethpage was recognized by the Credit Union Times as a trailblazer for political action in the credit union industry. Linda has also been honored for her work by local organizations, including the American Heart Association, Education and Assistance Corporation (EAC), Long Island Business News for the 40/40 and Top 50 Women awards, the Long Island Chapter of the Association of Fund Raising Professionals, and by the Long Island Press Power List as one of its 2016 50 Most Influential Long Islanders.