Hair and Fur-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCJROTC UNIFORM STANDARDS A

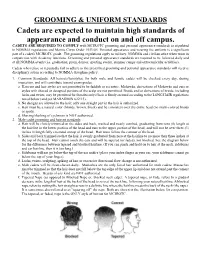

GROOMING & UNIFORM STANDARDS Cadets are expected to maintain high standards of appearance and conduct on and off campus. CADETS ARE REQUIRED TO COMPLY with MCJROTC grooming and personal appearance standards as stipulated in NOMMA regulations and Marine Corps Order 1533.6E. Personal appearance and wearing the uniform is a significant part of a cadet's MCJROTC grade. The grooming regulations apply to military, NOMMA and civilian attire when worn in conjunction with Academy functions. Grooming and personal appearance standards are required to be followed daily and at all NOMMA events (i.e. graduation, prom, dances, sporting events, summer camps and extracurricular activities). Cadets who refuse or repeatedly fail to adhere to the prescribed grooming and personal appearance standards will receive disciplinary action according to NOMMA discipline policy. 1. Common Standards: All haircuts/hairstyles, for both male and female cadets will be checked every day, during inspection, and will contribute toward exam grades. a. Haircuts and hair styles are not permitted to be faddish or eccentric. Mohawks, derivations of Mohawks and cuts or styles with shaved or designed portions of the scalp are not permitted. Braids and/or derivations of braids, including locks and twists, may be permitted for females only if hair is firmly secured according to the LONG HAIR regulations noted below (and per MARADMIN 622/15). b. No designs are allowed to the hair; only one straight part in the hair is authorized. c. Hair must be a natural color (blonde, brown, black) and be consistent over the entire head (no multi-colored braids or spots). d. Shaving/slashing of eyebrows is NOT authorized. -

Votiva Fractora Forma

Procedure Regular Price Special Event Price Neck Lift $3,900 $3120 Arms (bat wings) $4,900 $3920 Upper Abdomen $3,500 $2800 Lower Abdomen $3,500 $2800 Back / Bra Roll $3,500 $2800 Flanks (Love Handles) $3,900 $3120 Inner Thighs $3,900 $3120 Outer Thighs / Hips $3,900 $3120 Male Breast (Gynecomastia) $3,300 $2640 Knees $2,500 $2000 Multiple Procedures 10% off each additional site *Pricing dependent on size. VOTIVA Procedure Regular Price Special Event Price FormaV – scheduled every 2 weeks $1,895 for 3 sessions $1516 for 3 sessions FractoraV- done on 1st and 3rd Forma V appt $600 for 2 sessions $480 for 2 sessions FRACTORA High Energy, Radio Frequency Procedure Regular Price Special Event Price Series of 3 Series of 3 Face or INITIAL AREA $1,795 $1436 Face & Neck $2,295 $1836 Acne Treatment (back/shoulders) $1,795** $1436 Scar Treatment $595** $476 Pinning *Done every 4 – 6 weeks ** Pricing may vary on size FORMA Fractionated Radio Frequency Energy Procedure Regular Price Special Event Price Series of 6 Series of 6 Forma Plus $1,595 $1276 Forma $1,295 $1036 Forma Face/Neck $1,995 $1596 *1-2 times a week for 6 treatments BodyFX/MiniFX High Radio Frequency Energy, Fat Destruction Cellulite reduction, Body Tightening Procedure Body FX – Body FX- Mini FX - Mini FX- Regular SPECIAL Regular Price SPECIAL Price EVENT PRICE Series of 6 EVENT PRICE Series of 6 Series of 6 Series of 6 Single area $1,995 $1596 $1,195 $956 Additional 2nd Area $1,795 $1436 $955 $764 Additional 3rd Area $1,595 $1276 $765 $606 *2-3 times a week for 6 treatments Abdomen, -

List of Hairstyles

List of hairstyles This is a non-exhaustive list of hairstyles, excluding facial hairstyles. Name Image Description A style of natural African hair that has been grown out without any straightening or ironing, and combed regularly with specialafro picks. In recent Afro history, the hairstyle was popular through the late 1960s and 1970s in the United States of America. Though today many people prefer to wear weave. A haircut where the hair is longer on one side. In the 1980s and 1990s, Asymmetric asymmetric was a popular staple of Black hip hop fashion, among women and cut men. Backcombing or teasing with hairspray to style hair on top of the head so that Beehive the size and shape is suggestive of a beehive, hence the name. Bangs (or fringe) straight across the high forehead, or cut at a slight U- Bangs shape.[1] Any hairstyle with large volume, though this is generally a description given to hair with a straight texture that is blown out or "teased" into a large size. The Big hair increased volume is often maintained with the use of hairspray or other styling products that offer hold. A long hairstyle for women that is used with rich products and blown dry from Blowout the roots to the ends. Popularized by individuals such asCatherine, Duchess of Cambridge. A classic short hairstyle where it is cut above the shoulders in a blunt cut with Bob cut typically no layers. This style is most common among women. Bouffant A style characterized by smooth hair that is heightened and given extra fullness over teasing in the fringe area. -

Letstalk HAIR Everything You Need to Know to Grow It Treat Loss Luster It Keep It Proffesional

CAMPUS pages MAG 36 exclusive coontfent www.campusmag.co.ke VOL 2 | AUGUST 2018 LetsTalk HAIR Everything You Need To Know To Grow It Treat Loss Luster it Keep It Proffesional EXLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH MaryneKeseri FASHION FEATURE TECH DRESSING FOR WHY ARE MILLENIALS XIAOMI THE COLD WEATHER SO BROKE REDMI 5 PLUS editorial I like your hair by the way. I know this is an awkward way to start a magazine editorial but the perfect way to break the ice with someone. First let me thank you for picking up a copy of CampusMag's August Issue. Whether you just want to peruse a section or read through it, know that the magazine has been designed with you, the student in mind from the cover page to the last page. Thoughts and opinions on how to improve the magazine are always welcome. Be they be on how to improve on the design, the topics we cover or new sections you'd like to see, holla at us through our social media pages listed below or send us an email. Hair is an important part of everyone's everyday life and is a particularly a quite integral part to everyones success. How you keep and maintain it is what makes the phrase 'First Impressions last' matter as where do other start looking at your from if not your hair. On this months issue, we tackle some of the most important issues around hair such as how to organically grow it much longer, how to take care of it and most importantly, how to keep it professional. -

Medical Clinic

HENLEY CLINIC MEDICAL CLINIC – PRICE GUIDE Some Medical Treatments with the Medical Director may be priced approximately 5% above prices below FULL CONSULTATIONS ARE REQUIRED BEFORE ANY MEDICAL TREATMENTS CAN PROCEED FACIAL TREATMENTS – Btx-fillers-skin peels-skin quality Btx injectable = 1 facial area 210.00 Btx injectable = 2 facial areas 299.00 Btx injectable = 3 facial areas 399.00 Dermal Fillers (per syringe) From 330.00 Price will vary depending upon product used, Facial lines, lifting and wrinkles amount of filler required and areas treated. Lips and Peri-oral region From 395.00 Subsequent syringes used in same injection session, will be reduced price per syringe Volumising fillers From 450.00 As above for facial Volume Profhilo- Hyaluronic acid Injectable From 330.00 Skin Bio-remodelling treatment PRX-T33 – no needle skin peel for From 275.00 significantly improved skin quality COOLSCULPTING – Body Contouring / Fat Freezing Treatment Freeze away unwanted stubborn fat - no needles and no surgery From £525.00*-£700.00 per cycle Abdomen/stomach Back and bra fat Chin Discounts available on multiple Thighs areas and cycle treatments Upper arms/bingo wings Flank/mid lower back *Price for at least four treatment cycles ULTHERAPY – Face, Neck and Chest Ultrasound Treatment Under eye – Skin smoothing and fine line reduction Prices range from £275 to £2495 Upper face – Above and below eye area depending on area/s required to be Lower face – Cheeks, jawline, chin and jowls treated Neck – Under chin down to upper chest Reduced prices are -

Uniform Regulations, Comdtinst M1020.6K

Commander US Coast Guard Stop 7200 United States Coast Guard 2703 Martin Luther King Jr Ave SE Personnel Service Center Washington DC 20593-7200 Staff Symbol: PSC-PSD (mu) Phone: (202) 795-6659 COMDTINST M1020.6K 7 JUL 2020 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION M1020.6K Subj: UNIFORM REGULATIONS Ref: (a) Coast Guard External Affairs Manual, COMDTINST M5700.13 (series) (b) U. S. Coast Guard Personal Property Management Manual, COMDTINST M4500.5 (series) (c) Military Separations, COMDTINST M1000.4 (series) (d) Tattoo, Body Marking, Body Piercing, and Mutilation Policy, COMDTINST 1000.1 (series) (e) Coast Guard Pay Manual, COMDTINST M7220.29 (series) (f) Military Qualifications and Insignia, COMDTINST M1200.1 (series) (g) Coast Guard Military Medals and Awards Manual, COMDTINST M1650.25 (series) (h)Financial Resource Management Manual (FRMM), COMDTINST M7100.3 (series) (i) Rescue and Survival Systems Manual, COMDTINST M10470.10 (series) (j) Coast Guard Aviation Life Support Equipment (ALSE) Manual, COMDTINST M13520.1 (series) (k) Coast Guard Air Operations Manual, COMDTINST M3710.1 (series) (l) Coast Guard Helicopter Rescue Swimmer Manual, COMDTINST M3710.4 (series) (m) U. S. Coast Guard Maritime Law Enforcement Manual (MLEM), COMDTINST M16247.1 (series) (FOUO) [To obtain a copy of this reference contact Commandant (CG-MLE) at (202) 372-2164.] (n) Coast Guard Medical Manual, COMDTINST M6000.1 (series) (o) Standards For Coast Guard Personnel Wearing the Navy Working Uniform (NWU), COMDTINST 1020.10 (series) 1. PURPOSE. This Manual establishes the authority, policies, procedures, and standards governing the uniform, appearance, and grooming of all Coast Guard personnel Active, Reserve, Retired, Auxiliary and other service members assigned to duty with the Coast Guard. -

Outfitting Paris: Fashion, Space, and the Body in Nineteenth-Century French Literature

Outfitting Paris: Fashion, Space, and the Body in Nineteenth-Century French Literature and Culture by Kasia Stempniak Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Deborah Jenson, Supervisor ___________________________ David Bell ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Jessica Tanner Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Outfitting Paris: Fashion, Space, and the Body in Nineteenth-Century French Literature and Culture by Kasia Stempniak Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Deborah Jenson, Supervisor ___________________________ David Bell ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Jessica Tanner An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Kasia Stempniak 2019 Abstract This dissertation argues that the literary and cultural history of nineteenth- century Paris must be re-envisaged in the context of fashion as a spatial and embodied practice. While existing scholarship has focused on the role of fashion in emerging consumer culture, I focus instead on how clothing mediated bodily and urban knowledge. With the rise of department stores, the fashion press, and textile innovations in mid-nineteenth-century France, fashion became synonymous with the modern urban experience. Concomitantly with the emergence of the modern fashion system, the city of Paris was itself refashioned through vast urbanization projects. This metropolitan redesign created new points of intersection between the dressed body and the city. -

Hairstyle and Headgear Transgressions, and the Concept of Fuyao (Ornamentation Anomaly) in Early China

ornamentation anomaly in early china Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.1: 1-51 rebecca doran Hairstyle and Headgear Transgressions, and the Concept of Fuyao (Ornamentation Anomaly) in Early China abstract: Fuyao 服妖, or “ornamentation anomaly,” is a historical category of disaster (anom- aly) that emerged during the Han period. It is a rich example of the perceived connection between sumptuary transgression and political disorder in the Chi- nese cosmological and historical traditions. Due to the importance of hairstyle and headgear in the performance of state ritual ideology and hierarchical stratification, discussions of hairstyle and hair ornamentation represent an especially intriguing in- carnation of apprehension about improper personal appearance. The present paper approaches an understanding of the emergence and uses (historical and narrative) of fuyao mainly in the Han through Tang period through an examination of fuyao examples involving hairstyle and headgear. An analysis of hair-related fuyao within the rubrics provided by appearance or demeanor (mao 貌) as a moral and political marker and the ritual significance of headgear in the Chinese tradition indicates the use of fuyao as a medium of historical evaluation that becomes interwoven, in theory if not in practice, with the creation, promulgation, and subversion of culturally de- fined identities. keywords: hairstyle, headgear, fuyao, guan, sumptuary regulations, Treatise on the Five Phases y the third decade of the first century ad, Wang Mang’s 王莽 (ca. B 45 bc–23 ad) Xin 新 (9–23 ad) dynasty was swiftly unraveling, and new contenders for power emerged.1 One of the most prominent early figures who seemed poised to fill the power vacuum left by the demise of the Xin was Liu Xuan 劉玄 (d. -

Mohawk Hairstyle

Mohawk hairstyle The mohawk (also referred to as a mohican) is a hairstyle in which, in the most common variety, both sides of the head are shaven, leaving a strip of noticeably longer hair in the center. The mohawk is also sometimes referred to as an iro in reference to the Iroquois, from whom the hairstyle is derived - though historically the hair was plucked out rather than shaved. Additionally, hairstyles bearing these names more closely resemble those worn by the Pawnee, rather than the Mohawk, Mohican/Mahican, Mohegan, or other phonetically similar tribes. The red-haired Clonycavan Man bog body found in Ireland is notable for having a well-preserved Mohawk hairstyle, dated to between 392 BCE and 201 BCE. It is today worn as an emblem of non-conformity. The world record for the tallest mohawk goes to Kazuhiro Watanabe, who has a 44.6-inch tall mohawk.[1][1] (http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2012/9/record-h older-profile-kazuhiro-watanabe-tallest-mohican-44821) Contents A young man wearing a mohawk Name Historical use Style and maintenance Varieties Classic (1970s–1980s) Modern (post-1990) Fauxhawk variants See also References External links Paratroopers of the 101st Name Airborne Division in 1944 While the mohawk hairstyle takes its name from the people of the Mohawk nation, an indigenous people of North America who originally inhabited the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York,[2] the association comes from Hollywood and more specifically from the popular 1939 movie Drums Along the Mohawk starring Henry Fonda. The Mohawk and the rest of the Iroquois confederacy (Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Tuscarora and Oneida) in fact wore a square of hair on the back of the crown of the head. -

A Visual Analysis of Natural Hair And

THESIS WORKING ON MY HAIR: A VISUAL ANALYSIS OF NATURAL HAIR AND BLACK WOMEN PROFESSIONALS IN POPULAR TELEVISION PROGRAMMING Submitted by Hayley Eve Blackburn Department of Journalism and Media Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2017 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Gayathri Sivakumar Rosa Mikeal Martey Katie Gibson Copyright by Hayley Eve Blackburn 2017 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT WORKING ON MY HAIR: A VISUAL ANALYSIS OF NATURAL HAIR AND BLACK WOMEN PROFESSIONALS IN POPULAR TELEVISION PROGRAMMING I examine the representations of Black women characters in professional settings on seven television drama texts. Black features are subjected to Eurocentering—the reduction of racial heritage markers to align with Eurocentric values—to protect hegemonic traditions under the guise of racial neoliberalism. This study focuses on hairstyles for Black women because hair functions as a racial signifier to the audience and is thus a key component of the visual rhetoric under observation. I answer the research question: how does the visibility and representation of natural hair invite the audience to discipline Blackness in professional spaces. The findings reflect that natural hair does lack visibility, with less than 25% of the sample representing significant moments for the main characters to interact with natural hair, and when visible the representation tends towards a disciplinary frame. Natural hair is a symbol of the Black savage framing that reinforces the superiority of Whiteness in the professional world. The Black woman with altered hair becomes a symbol for a civilized, thus successful, Black body able to participate in a professional society while natural hair remains the symbol for the opposite. -

Design Board Catalog

® Innovative Designs for Quilters and Crafters Featuring Butterfly - Purple Dotz - Applique Design Board Catalog Fall 2020 Bellflower Design Board © Patricia E. Ritter urban elementz ® Design Boards Design boards are made of a strong, light-weight PVC like material with nonskid backing. Multiple boards can be connected end-to-end to make longer boards. Connectors are supplied when ordering multiple quantities of the same design. These design boards are made to be used with a stylus. © All rights reserved. Copyright and designer info available upon request All design boards are priced individually at the suggested retail price. Design board sets include two of the same design boards to create a larger overall design. The set size listed is the total size of these two boards together. ® To see our entire selection of: Pantographs Tear Away Stencils Design Boards Appliqué Elementz Tattoo Elementz - Decorative Decals Patterns and Books Quilting Accessories Visit our website at: www.urbanelementz.com 125 sunny creek new braunfels . texas . 78132 830 . 964 . 6133 2-Ply A Little Bit This Abacus Abigail Design Size - 10” x 22.25” Design Size - 10” x 23.5” Design Size - 10.5” x 22” Design Size - 8.25” x 28” $ 48.95 $ 48.95 $ 48.95 $ 52.95 Abigail - Grande - Set Abigail - Petite Abracadabra Abundant Leaves Set Size - 10” x 34” Design Size - 4” x 27.25” Design Size - 9.25” x 23.5” Single Row Size - 6” x 21” $ 62.95 $ 42.95 $ 48.95 $ 48.95 African Samba Agave Agave - Block #1 Agave - Block #2 Design Size - 9” x 26” Design Size - 10.5” x 28” Design -

Sponsor Form

10th Annual Southeastern Beard & Moustache Championships Sponsorship Form Dear Valued Sponsor: The Holy City Beard & Moustache Society would like you to participate in our 10th Annual Southeastern Beard & Moustache Championships as a sponsor! Last year we had over 150 contestants, 600 spectators & raised $8,000 for Big Brothers Big Sisters of Charleston & Low County Women With Wings. This year will be a charity event for Big Brothers Big Sisters of Charleston. Their mission is to provide children facing adversity with strong and enduring, professionally supported one-to-one relationships that change their lives for the better, forever. By partnering with parents/guardians, volunteers and others in the community we are accountable for each child in our program achieving: Higher aspirations, greater confidence, and better relationships by Avoidance of risky behaviors, and Educational success. The event is scheduled during Memorial Day Weekend on May 25th at 7:00pm at the Music Farm in downtown Charleston. The categories include sideburns, goatee, moustache (natural & styled), junior beard, college beard, full beard styled moustache, freestyle, ladies artificial (creative & realistic), gray beard, best in show and full beard natural over 12 inches & under 12 inches. Below are the levels that you may participate at: Platinum Level (aka Full Beard) - $1000 Gold Level (aka Goatee) - $ 500 Silver Level (aka Moustache) - $300 Bronze Level (aka Sideburn) - $150 In Kind Donations Accepted For title sponsorship, please contact us: [email protected]