A Night at the Opera: Performance, Theatricality, and Identity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

M-Ad Shines in Toronto

Volume 44, Issue 3 SUMMER 2013 A BULLETIN FOR EVERY BARBERSHOPPER IN THE MID-ATLANTIC DISTRICT M-AD SHINES IN TORONTO ALEXANDRIA MEDALS! DA CAPO maKES THE TOP 10 GImmE FOUR & THE GOOD OLD DAYS EARN TOP 10 COLLEGIATE BROTHERS IN HARMONY, VOICES OF GOTHam amONG TOP 10 IN THE WORLD WESTCHESTER WOWS CROWD WITH MIC-TEST ROUTINE ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, FRANK THE DOG HIT TOP 20 UP ALL NIGHT KEEPS CROWD IN STITCHES CHORUS OF THE CHESAPEAKE, BLACK TIE AFFAIR GIVE STRONG PERFORmaNCES INSIDE: 2-6 OUR INTERNATIONAL COMPETITORS 7 YOU BE THE JUDGE 8-9 HARMONY COLLEGE EAST 10 YOUTH CamP ROCKS! 11 MONEY MATTERS 12-15 LOOKING BACK 16-19 DIVISION NEWS 20 CONTEST & JUDGING YOUTH IN HARMONY 21 TRUE NORTH GUIDING PRINCIPLES 23 CHORUS DIRECTOR DEVELOPMENT 24-26 YOUTH IN HARMONY 27-29 AROUND THE DISTRICT . AND MUCH, MUCH MORE! PHOTO CREDIT: Lorin May ANYTHING GOES! 3RD PLACE BRONZE MEDALIST ALEXANDRIA HARMONIZERS PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS ON STAGE IN TORONTO. INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: QUARTET CONTEST ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT, T.J. Carollo, Jeff Glemboski, Larry Bomback and Wayne Grimmer placed 12th. All photos courtesy of Dan Wright. To view more photos, go to www. flickr.com/photosbydanwright UP ALL NIGHT, John Ward, Cecil Brown, Dan Rowland and Joe Hunter placed 28th. DA CAPO, Ryan Griffith, Anthony Colosimo, Wayne FRANK THE Adams and Joe DOG, Tim Sawyer placed Knapp, Steve 10th. Kirsch, Tom Halley and Ross Trube placed 20th. MID’L ANTICS SUMMER 2013 pa g e 2 INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION 2013: COLLEGIATE QUARTETS THE GOOD OLD DAYS, Fernando Collado, Doug Carnes, Anthony Arpino, Edd Duran placed 10th. -

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 2017 This List Is Compiled Based on Over 2 Million Song Requests Made Using the DJ Event Planner Song Request System

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs In 2017 This list is compiled based on over 2 million song requests made using the DJ Event Planner song request system. Rank Song Song Title 1 Mark Ronson feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Killers Mr. Brightside 3 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 4 Pharrell Williams Happy 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire 7 Bryan Adams Summer Of '69 8 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 9 ABBA Dancing Queen 10 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 11 Bruno Mars Marry You 12 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 13 Dexys Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 14 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 15 Queen Don't Stop Me Now 16 Rihanna feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 17 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 18 Ed Sheeran Shape Of You 19 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 20 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 21 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 22 Beyonce feat. Jay-Z Crazy In Love 23 Oasis Wonderwall 24 Wham! Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go 25 B-52's Love Shack 26 John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John Grease Megamix 27 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 28 Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger 29 Los Del Rio Macarena 30 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 31 Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O' Mine 32 Toploader Dancing In The Moonlight 33 Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor 34 Mark Ronson feat. Amy Winehouse Valerie 35 House Of Pain Jump Around 36 Stevie Wonder Superstition 37 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

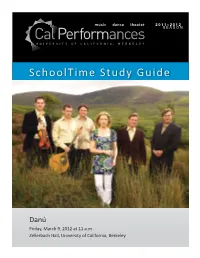

Danu Study Guide 11.12.Indd

SchoolTime Study Guide Danú Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 am, your class will a end a performance by Danú the award- winning Irish band. Hailing from historic County Waterford, Danú celebrates Irish music at its fi nest. The group’s energe c concerts feature a lively mix of both ancient music and original repertoire. For over a decade, these virtuosos on fl ute, n whistle, fi ddle, bu on accordion, bouzouki, and vocals have thrilled audiences, winning numerous interna onal awards and recording seven acclaimed albums. Using This Study Guide You can prepare your students for their Cal Performances fi eld trip with the materials in this study guide. Prior to the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student resource sheet on pages 2 & 3 and hand it out to your students several days before the performance. • Discuss the informa on About the Performance & Ar sts and Danú’s Instruments on pages 4-5 with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 6-8 and About Ireland on pages 9-11. • Engage your students in two or more of the ac vi es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding ques ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 9. • Immerse students further into the art form by using the glossary and resource sec ons on pages 12 &15. At the performance: Students can ac vely par cipate during the performance by: • LISTENING CAREFULLY to the melodies, harmonies and rhythms • OBSERVING how the musicians and singers work together, some mes playing in solos, duets, trios and as an ensemble • THINKING ABOUT the culture, history, ideas and emo ons expressed through the music • MARVELING at the skill of the musicians • REFLECTING on the sounds and sights experienced at the theater. -

2021 Cyclist Bible 2021 Cyclist

2021 CYCLIST BIBLE 39TH ANNUAL LOGAN, UTAH TO JACKSON HOLE, WYOMING BIKE RACE HOW IT ALL BEGAN The LoToJa was started in 1983 by two Logan cyclists, David Bern, a student at Utah State University, and Jeff Keller, the owner of Sunrise Cyclery. The two men wanted a race that resembled the difficulty of a one-day European classic, like Paris-Roubaix or the Tour of Flanders. LoToJa's first year featured seven cyclists racing 192 miles from Logan to a finish line in Jackson's town square. The winning time was just over nine hours by Logan cyclist, Bob VanSlyke. Since then, LoToJa has grown into one of the nation’s premier amateur cycling races and continues to be a grueling test of one's physical and mental stamina. Many compete to win their respective category, while others just ride to cross the finish line. At 200+ miles, LoToJa is the longest one-day USAC-sanctioned bicycle race in the country. Thank you for riding with us! Cover art courtesy of David V. Gonzales - davidvgonzalesart.com Photos provided by Snake River Photo - snakeriverphoto.com WELCOME TO LOTOJA INSIDE THIS GUIDE 1 — Event Schedule 15 — Crew Guidelines & Information 2 — Check-in/Packet Pickup 17 — Crew Vehicle Drive Distance Schedule 2 — Podium Awards & Protest Period 18 — Crew Driving Directions 3 — 2021 Start Schedule 19 — Cyclist Care / First-Aid Reminders 4 — Timing Chip, Finish Line, and Results 21 — Course Elevations and Map 5 — Cyclist Information 23 — Logan to Preston • Leg 1 Information 7 — Cyclist Guidelines 25 — Preston to Montpelier • Leg 2 Information 9 — Feed Zone Information 27 — Montpelier to Afton • Leg 3 Information 11 — Relay Team Guidelines 29 — Afton to Alpine • Leg 4 Information 12 — Additional Safety Guidelines 31 — Alpine to Finish • Leg 5 Information 13 — Veteran Advice 33 — King/Queen of Mtn. -

Freddie Mercury's Bicycle Race Turns Real 42 Years On

ANEESH PHADNIS RAM PRASAD SAHU SHINE JACOB ARUP ROYCHOUDHURY TAMAL BANDYOPADHYAY SUDIPTO DEY JOYDEEP GHOSH Freddie Mercury’s bicycle race turns real 42 years on ISHITA AYAN DUTT excitement around bicycles and you as gyms continue to remain shut. It’s Kolkata, 19 July are talking to a 57-year-old man,” COVID NO SPOKE good to see women also joining in,” said Pankaj M Munjal, chairman IN THE WHEEL FOR said a professional cyclist. Bicycle, bicycle, bicycle and managing director, Hero Motors The new entrants to the cycling I want to ride my bicycle, bicycle, Company (HMC). PEDAL PUSHERS arena are either gym goers trying to get bicycle... Hero has a 43 per cent share in the | Hero has seen 50% increase their dose of cardio, or people cooped 16-million Indian bicycle market. in demand for premium bicycles; up at home wanting to catch a breath Freddie Mercury of the British HMC plants are working overtime, demand for e-bikes shot up by of fresh air with some physical activity rock band Queen penned the song at about 110 per cent. “We are working almost 100% after lockdown thrown in. Either way, cycling just Bicycle Race in 1978 inspired by on Saturdays and Sundays,” he said. | Decathlon Sports India has seen got a fresh lease on life. Tour de France, the famed multiple Small wonder, given it had A spokesperson for Decathlon stage bicycling race. But 42 years later, orders for 500,000 bicycles in June, more than 45% cent year-on-year Sports India (DSI), the Indian arm of the Covid-19 pandemic has pushed compared to actual sales of 350,000 growth in sales in June and July the French sporting goods retailer, everyone into singing the same tune. -

A Classical View of the Business Cycle

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES A CLASSICAL VIEW OF THE BUSINESS CYCLE Michael T. Belongia Peter N. Ireland Working Paper 26056 http://www.nber.org/papers/w26056 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2019 We are especially grateful to David Laidler for his encouragement during the development of this paper and to John Taylor, Kenneth West, two referees, and seminar participants at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta for helpful comments on previous drafts. All errors that remain are our own. Neither of us received any external support for, or has any financial interest that relates to, the research described in this paper. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2019 by Michael T. Belongia and Peter N. Ireland. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. A Classical View of the Business Cycle Michael T. Belongia and Peter N. Ireland NBER Working Paper No. 26056 July 2019 JEL No. B12,E31,E32,E41,E43,E52 ABSTRACT In the 1920s, Irving Fisher extended his previous work on the Quantity Theory to describe, through an early version of the Phillips Curve, how changes in the money stock could be associated with cyclical movements in output, employment, and inflation. -

What Classical Music Is (Not the Final Text, but a Riff on What

Rebirth: The Future of Classical Music Greg Sandow Chapter 4 – What Classical Music Is (not the final text, but a riff on what this chapter will say) In this chapter, I’ll try to define classical music. But why? Don’t we know what it is? Yes and no. We’re not going to confuse classical music with other kinds of music, with rock, let’s say, or jazz. But can we say how we make these distinctions? You’d think we could. And yet when we look at definitions of classical music—either formal ones, in dictionaries, or informal ones, that we’d deduce by looking around at the classical music world—we run into trouble. As we’ll see, these definitions imply that classical music is mostly old music (and, beyond that, old music only of a certain kind). And they’re full of unstated assumptions about classical music’s value. These assumptions, working in the background of our thoughts, make it hard to understand what classical music really is. We have to fight off ideas about how much better it might be than other kinds of music, ideas which—to people not involved with classical music, the very people we need to recruit for our future audience—can make classical music seem intimidating, pompous, unconvincing. And so here’s a paradox. When we expose these assumptions, when we develop a factual, value-free definition of classical music, only then can we find classical music’s real value, and convincingly set out reasons why it should survive. [2] Let’s start with common-sense definition of classical music, the one we all use, without much thought, when we say we know what classical music is when we hear it. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business.