View the World Through Protestant Eyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

A Reply to Morton on Psalmody

— : A REPLY MORTON ON PSALMODY TO WHICH is ADDED A CONDENSED ARGUMENT FOR tllE EXCLUSIVE- USE OF AN INSPIRED PSALMODY, ROBERT J. DODDS, BfiNISTER, OF THE GtOSPEL IN THE REFORMED PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own conceit. Prov. 26:5. PITTSBURGH KENNEDY & BROTHER, PUBLISHERS, THIRD STREET. 1861. ' • ERRATA. The author not having had an opportunity of correcting the proof sheets of the first part of this work, the reader will please correct the following errors. Page 17, line 9, for '*' cant," read '' rant." " " " 22, for " invite," read " indite." " 23, '' 4, for " illiberality," read " liberality." " 33, "1-2, for " the divine," read "a divine person, the" " 34, " 8, after the word fZeac?, insert "And when, Bro. Morton, could we learn from any book in the Bible that the son of Joseph and Mary attested his Messiahship by raising Lazarus from the dead." Page 42, line 11, for "religion," read "religious faith." " 44. " 22, for " Lord," read " word." PREFACE. The work to which the followmg pages are intend- ed as a reply, purports to be a review of Dr. Pressly on Psalmody, by Rev. George Morton, of the Pres- byterian Church. Mr. Morton would, so far as I am concerned, have remained forever unnoticed, had he not made a foul attack upon that version of the Psalms which is sung in the church to which I have the honor to belong, and in sundry other Presbyte- rian Churches of high respectability. I am far from having so low an opinion of Mr. -

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos. 4–6 Arranged for Two Guitars Montenegrin Guitar Duo Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) with elegantly broken chords. This is interrupted by a The contrasting pair of Gavottes with a perky walking bass English Suites Nos. 4–6, BWV 809–811 sudden burst of semiquavers leading to a moment’s accompaniment brings in the atmosphere of a pastoral reflection before plunging into an extended and brilliant dance in the market square. The second Gavotte evokes (Arranged for two guitars by the Montenegrin Guitar Duo) fugal Allegro. Of the Préludes in the English Suites this is images of wind instruments piping together in rustic chorus. The English Suites is the title given to a set of six suites for Bach scholar, David Schulenberg has observed that while the longest and most elaborate. The Allemande which The Gigue, in 12/16 metre, is virtuosic in both keyboard believed to have been composed between 1720 the beginning of the Gigue presents a normal three-part follows is, in comparison, an oasis of calm, with superb compositional aspects and the technical demands on the and the early 1730s. During this period, Bach also explored fugal exposition, from then on, no more than two voices are contrapuntal writing and ingenious tonal modulations. The performers. Bach’s incomparable art of fugal writing is at the suite form in the six French Suites and the seven large heard at a time. Courante unites a French-style melodic line with a full stretch here, the second half representing, as in mirror suites under the title of Partitas (six in all) and an English Suite No. -

Johann Sebastian Bach's St. John Passion from 1725: a Liturgical Interpretation

Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. John Passion from 1725: A Liturgical Interpretation MARKUS RATHEY When we listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s vocal works today, we do this most of the time in a concert. Bach’s passions and his B minor Mass, his cantatas and songs are an integral part of our canon of concert music. Nothing can be said against this practice. The passions and the Mass have been a part of the Western concert repertoire since the 1830s, and there may not have been a “Bach Revival” in the nineteenth century (and no editions of Bach’s works for that matter) without Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s concert performance of the St. Matthew Passion in the Berlin Singakademie in 1829.1 However, the original sitz im leben of both large-scaled works like his passions, and his smaller cantatas, is the liturgy. Most of his vocal works were composed for use during services in the churches of Leipzig. The pieces unfold their meaning in the context of the liturgy. They engage in a complex intertextual relationship with the liturgical texts that frame them, and with the musical (and theological) practices of the liturgical year of which they are a part. The following essay will outline the liturgical context of the second version of the St. John Passion (BWV 245a) Bach performed on Good Friday 1725 in Leipzig. The piece is a revision of the familiar version of the passion Bach had composed the previous year. The 1725 version of the passion was performed by the Yale Schola Cantorum in 2006, and was accompanied by several lectures I gave in New Haven and New York City. -

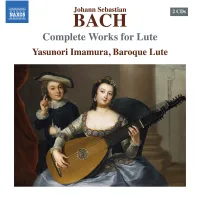

Imamura-Y-S03c[Naxos-2CD-Booklet

573936-37 bk Bach EU.qxp_573936-37 bk Bach 27/06/2018 11:00 Page 2 CD 1 63:49 CD 2 53:15 CD 2 Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 1Partita in E major, BWV 1006a 20:41 1Suite in E minor, BWV 996 18:18 # # Prelude 2:51 Consider, O my soul 2 Prelude 4:13 2 Betrachte, meine Seel’ Allemande 3:02 3 Loure 3:58 3 Betrachte, meine Seel’, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen, Consider, O my soul, with fearful joy, consider, Courante 2:40 4 Gavotte en Rondeau 3:29 4 Mit bittrer Lust und halb beklemmtem Herzen in the bitter anguish of thy heart’s affliction, Sarabande 4:24 5 Menuet I & II 4:43 5 Dein höchstes Gut in Jesu Schmerzen, thy highest good is Jesus’ sorrow. Bourrée 1:33 6 Bourrée 1:51 6 Wie dir auf Dornen, so ihn stechen, For thee, from the thorns that pierce Him, Gigue 2:27 Gigue 3:48 Die Himmelsschlüsselblumen blühn! what heavenly flowers spring. Du kannst viel süße Frucht von seiner Wermut brechen Thou canst the sweetest fruit from his wormwood gather, 7Suite in C minor, BWV 997 22:01 7Suite in G minor, BWV 995 25:15 Drum sieh ohn Unterlass auf ihn! then look on Him for evermore. Prelude 6:11 8 Prelude 3:11 8 Allemande 6:18 9 Fugue 7:13 9 Sarabande 5:28 0 Courante 2:35 Recitativo from St Matthew Passion, BWV 244b 0 $ $ Gigue & Double 6:09 ! Sarabande 2:50 Gavotte I & II 4:43 Ja freilich will in uns Yes! Willingly will we ! @ Prelude in C minor, BWV 999 1:55 Gigue 2:38 Ja freilich will in uns das Fleisch und Blut Yes! Willingly will we, Flesh and blood, Zum Kreuz gezwungen sein; Be brought to the cross; @ Fugue in G minor, BWV 1000 5:46 #Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 2:24 Je mehr es unsrer Seele gut, The harsher the pain Arioso: Betrachte, meine Seel’ Je herber geht es ein. -

Southern California Junior Bach Festival

The SCJBF 3 year, cyclical repertoire list for the Complete Works Audition Students may enter the Complete Works Audition (CWA) only once each year as a soloist on the same instrument and must perform the same music in the same category that they performed at the Branch and Regional Festivals, but complete as indicated on this list. Students will be disqualified if photocopied music is presented to the judges or used by accompanists (with the exception of facilitating page turns). Note: Repertoire lists for years in parentheses are not finalized and are subject to change Category I – SHORT PRELUDES AND FUGUES Year Composition BWV Each year Select any two of the following: Preludes: BWV 924-943 and 999 Fugues: BWV 952, 953 and 961 Select one of the following: 1. Prelude and Fugue in a m 895 2. Prelude and Fughetta in d m 899 3. Prelude and Fugue in e m 900 4. Prelude and Fughetta in G M 902 Category II – VARIOUS DANCE MOVEMENTS The dance movements listed below – from one of the listed Suites or Partitas – are required for the Complete Works Audition. Year Composition BWV 2021 English Suites: 1. From the A Major #1 806 The Bourree I and the Bourree II 2. From the e minor #5 810 The Passepied I and the Passepied II French Suites: 1. From the d minor #1 812 The Menuet I and the Menuet II 2. From the G Major #5 816 The Gavotte, Bourree and Loure Partitas: 1. From the a min or #3 827 The Burlesca and the Scherzo 2. -

Bärenreiter Organ Music

>|NAJNAEPAN KNC=JIQOE? .,-.+.,-/ 1 CONTENTS Organ Music Solo Voice and Organ ...............30 Index by Collections and Series ...........4–13 Books............................................... 31 Edition Numbers ....................... 34 Composers ....................................14 Contemporary Music Index by Jazz .............................................. 29 A Selection ..............................32 Composers / Collections .........35 Transcriptions for Organ .........29 Photo: Edition Paavo Blåfi eld ABBREVIATIONS AND KEY TO FIGURES Ed. Editor Contents Ger German text Review Eng English text Content valid as of May 2012. Bärenreiter-Verlag Fr French text Errors excepted and delivery terms Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG Lat Latin text subject to change without notice. International Department BA Bärenreiter Edition P.O. Box 10 03 29 H Bärenreiter Praha Cover design with a photograph D-34003 Kassel · Germany SM Süddeutscher Musikverlag by Edition Paavo Blåfi eld. Series E-Mail: paavo@blofi eld.de www.baerenreiter.com a.o. and others www.blofi eld.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed in Germany 3/1206/10 · SPA 238 2 Discover Bärenreiter … www.baerenreiter.com Improved Functionality Simple navigation enables quick orientation Clear presentation Improved Search Facility Comprehensive product information User-friendly searches by means of keywords Product recommendations Focus A new area where current themes are presented in detail … the new website3 ORGAN Collections and Series Enjoy the Organ Ave Maria, gratia plena Ave-Maria settings The new series of easily playable pieces for solo voice and organ (Lat) BA 8250 page 30 Enjoy the Organ I contains a collection of stylistically varied Bärenreiter Organ Albums pieces for amateur organists Collections of organ pieces which are equally suitable for page 6-7 use in church services and in concerts. -

Abuses Under Indictment at the Diet of Augsburg 1530 Jared Wicks, S.J

ABUSES UNDER INDICTMENT AT THE DIET OF AUGSBURG 1530 JARED WICKS, S.J. Gregorian University, Rome HE MOST recent historical scholarship on the religious dimensions of Tthe Diet of Augsburg in 1530 has heightened our awareness and understanding of the momentous negotiations toward unity conducted at the Diet.1 Beginning August 16, 1530, Lutheran and Catholic represent atives worked energetically, and with some substantial successes, to overcome the divergence between the Augsburg Confession, which had been presented on June 25, and the Confutation which was read on behalf of Emperor Charles V on August 3. Negotiations on doctrine, especially on August 16-17, narrowed the differences on sin, justification, good works, and repentance, but from this point on the discussions became more difficult and an impasse was reached by August 21 which further exchanges only confirmed. The Emperor's draft recess of September 22 declared that the Lutheran confession had been refuted and that its signers had six months to consider acceptance of the articles proposed to them at the point of impasse in late August. Also, no further doctrinal innovations nor any more changes in religious practice were to be intro duced in their domains.2 When the adherents of the Reformation dis sented from this recess, it became unmistakably clear that the religious unity of the German Empire and of Western Christendom was on the way to dissolution. But why did it come to this? Why was Charles V so severely frustrated in realizing the aims set for the Diet in his conciliatory summons of January 21, 1530? The Diet was to be a forum for a respectful hearing of the views and positions of the estates and for considerations on those steps that would lead to agreement and unity in one church under Christ.3 1 The most recent stage of research began with Gerhard Müller, "Johann Eck und die Confessio Augustana/' Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Biblio theken 38 (1958) 205-42, and continued in works by Eugène Honèe and Vinzenz Pfhür, with further contributions of G. -

Remes Essay NEW for ONLINE

TEXTUAL ILLUSTRATION IN J.S. BACH’S SETTINGS OF O LAMM GOTTES, UNSCHULDIG Derek Remes Eastman School of Music [email protected] www.derekremes.com May, 2015 !1 J.S. Bach set the tune O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig six times in his surviving works. [slide 2] The settings range from early to late works, and vary widely in instrumentation, length, and complexity. Because this tune was always paired with the same text, we are afforded an opportunity to compare how Bach treated the same text in a variety of contexts. As we will see, Bach consistently used chromaticism, diminished seventh chords, and suspensions—that is, dissonance—at certain poignant words, implying that these techniques carried specific extramusical meaning in these contexts. These associations between text and compositional technique enhance our understanding of Bach’s musical vocabulary. [Slide 3] The text of O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig was written by Nicolaus Decius in 1531.1 There are three Low German hymns ascribed to him, each intended to replace portions of the Latin Ordinary: Hyllich ys Godt de vader (Sanctus), Allein Gott in der höh sei ehr (Gloria in excelsis), and O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig (Agnus Dei). These three texts are the oldest evangelical hymns, preceding Luther’s first chorale texts by almost a year.2 O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig is an expanded translation of the Agnus Dei, the more literal German translation being the text Christe, du Lamm Gottes, both shown in the table. Christe, du Lamm Gottes is paired with a different tune, which Bach set in the Orgelbüchlein as BWV 619, and again in the cantata Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn, BWV 23. -

The Neumeister Collection of Chorale Preludes of the Bach Circle: an Examination of the Chorale Preludes of J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 "The eumeiN ster collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works Sara Ann Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Sara Ann, ""The eN umeister collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 77. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/77 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NEUMEISTER COLLECTION OF CHORALE PRELUDES OF THE BACH CIRCLE: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CHORALE PRELUDES OF J. S. BACH AND THEIR USAGE AS SERVICE MUSIC AND PEDAGOGICAL WORKS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts Sara Ann Jones B. A., McNeese State University -

GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No

BHP 901 - BACH: GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No. 5 in e - Millicent Silver, Harpsichord _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ This disc, the first in our Heritage Performances Series, celebrates the career and the artistry of Millicent Silver, who for some forty years was well-known as a regular performer in London and on BBC Radio both as soloist and as harpsichordist with the London Harpsichord Ensemble which she founded with her husband John Francis. Though she made very few recordings, we are delighted to preserve this recording of the Goldberg Variations for its musical integrity, its warmth, and particularly the use of tonal dynamics (adding or subtracting of 4’ and 16’ stops to the basic 8’) which enhances the dramatic architecture. Millicent Irene Silver was born in South London on 17 November 1905. Her father, Alfred Silver, had been a boy chorister at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor where his singing attracted the attention of Queen Victoria, who had him give special performances for her. He earned his living playing the violin and oboe. His wife Amelia was an accomplished and busy piano teacher. Millicent was the second of their four children, and her musical talent became evident in time-honoured fashion when she was discovered at the age of three picking out on the family’s piano the tunes she had heard her elder brother practising. Eventually Millicent Silver won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London where, as was more common in those days, she studied equally both piano and violin. She was awarded the Chappell Silver Medal for piano playing and, in 1928, the College’s Tagore Gold Medal for the best student of her year.