Refusing to Be a Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pornography, Morality, and Harm: Why Miller Should Survive Lawrence

File: 02-DIONNE-Revised.doc Created on: 3/12/2008 1:29 PM Last Printed: 3/12/2008 1:34 PM 2008] 611 PORNOGRAPHY, MORALITY, AND HARM: WHY MILLER SHOULD SURVIVE LAWRENCE Elizabeth Harmer Dionne∗ INTRODUCTION In 2003, a divided Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas1 declared that morality, absent third-party harm, is an insufficient basis for criminal legis- lation that restricts private, consensual sexual conduct.2 In a strongly worded dissent, Justice Scalia declared that this “called into question” state laws against obscenity (among others), as such laws are “based on moral choices.”3 Justice Scalia does not specifically reference Miller v. Califor- nia,4 the last case in which the Supreme Court directly addressed the issue of whether the government may suppress obscenity. However, if, as Justice Scalia suggests, obscenity laws have their primary basis in private morality, the governing case that permits such laws must countenance such a moral basis. The logical conclusion is that Lawrence calls Miller, which provides the legal test for determining obscenity, into question.5 ∗ John M. Olin Fellow in Law, Harvard Law School. Wellesley College (B.A.), University of Cambridge (M. Phil., Marshall Scholar), Stanford Law School (J.D.). The author thanks Professors Frederick Schauer, Thomas Grey, and Daryl Levinson for their helpful comments on this Article. She also thanks the editorial staff of GEORGE MASON LAW REVIEW for their able assistance in bringing this Article to fruition. 1 539 U.S. 558 (2003). 2 Id. at 571 (“The issue is whether the majority may use the power of the state to enforce these views on the whole society through operation of the criminal law. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

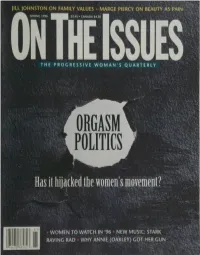

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL How to cite: MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL (2014) Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10818/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 “Not Andrea”: The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin Submitted for the degree of Masters by Research in English Literature By Isobel MacBrayne 1 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 4 Chapter I – Re-assessing the Feminist Polemic and its Relation to Fiction 10 Chapter II – Intertextuality in Dworkin’s Fiction 32 Chapter III – The construction of Dworkin and Her Media Representation 65 Conclusion 97 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Durham University for giving me this opportunity, the staff of the English Department, and all the admin and library staff whose time and hard work too often goes unnoticed. -

Confronting Pornography: Some Conceptual Basics Rebecca Whisnant University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Philosophy Faculty Publications Department of Philosophy 2004 Confronting Pornography: Some Conceptual Basics Rebecca Whisnant University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/phl_fac_pub Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons eCommons Citation Whisnant, Rebecca, "Confronting Pornography: Some Conceptual Basics" (2004). Philosophy Faculty Publications. 167. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/phl_fac_pub/167 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Rebecca Whisnant Confronting pornography: Some conceptual basics Porn takes over There can be no doubt, at this moment in history, that pornography is a truly massive industry saturating the human community. According to one set of numbers, the US porn industry's revenue went from $7 million in 1972 to $8 billion in 1996 ... and then to $12 billion in 2000.1 Now I'm no economist, and I understand about inflation, but even so, it seems to me that a thousand fold increase in a particular industry's revenue within 25 years is something that any thinking person has to come to grips with. Something is happening in this culture, and no person's understanding of sexuality or experience of relationships can be unaffected. The technologies of pornography are ever more dynamic. Obviously, video porn was a huge step up from magazines and even from film. -

Dworkin, Andrea (1946-2005) by Linda Rapp

Dworkin, Andrea (1946-2005) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Controversial radical feminist Andrea Dworkin wrote and spoke extensively regarding the cultural subjugation of women. She was particularly vigorous in her opposition to pornography. While some considered her a heroine for her attacks on patriarchy, others found her polemical pronouncements too extreme to be taken seriously. Andrea Dworkin, born September 26, 1946, came from a middle-class family in Camden, New Jersey. Rather curiously, the woman who would later decry men as moral cretins was close to her father, whom she credited with making her aware of the importance of social activism, and to her younger brother, but she did not get along well with her mother. In her book Life and Death: Unapologetic Writings on the Continuing War against Women (1997), Dworkin recalled traumatic events of her childhood, including being raped by a stranger at age nine and seduced by one of her high school teachers. Dworkin enrolled as a literature major at Bennington College in Vermont in 1964. While studying there, she periodically traveled to New York City to participate in protests against the war in Vietnam. On one such occasion in February 1965 she was arrested and held in the Women's House of Detention for several days, during which time she was subjected to humiliating strip searches and painful examinations by doctors. Upon being released, she took her story to the press. An investigation of the jail ensued, and it was eventually closed. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

Facts and Fictions: Feminist Literary Criticism and Cultural Critique, 1968-2012 by Leah Claire Allen Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman, Supervisor ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Priscilla Wald Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT Facts and Fictions: Feminist Literary Criticism and Cultural Critique, 1968-2012 by Leah Claire Allen Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman, Supervisor ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Priscilla Wald An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v Copyright by Leah Claire Allen © 2014 Abstract “Facts and Fictions: Feminist Literary Criticism and Cultural Critique, 1968- 2012” is a critical history of the unfolding of feminist literary study in the US academy. It contributes to current scholarly efforts to revisit the 1970s by reconsidering often- repeated narratives about the critical naivety of feminist literary criticism in its initial articulation. As the story now goes, many of the most prominent feminist thinkers of the period engaged in unsophisticated literary analysis by conflating lived social reality with textual representation when they read works of literature as documentary evidence of real life. As a result, the work of these “bad critics,” particularly Kate Millett and Andrea Dworkin, has not been fully accounted for in literary critical terms. -

General Editor's Introduction

General Editor’s Introduction PAISLEY CURRAH n the last decade, movements for transgender equality appear to have advanced I with astonishing speed, while other issues of concern to women’s movements have largely stalled, either making little progress (equal pay) or suffering real set- backs (abortion access). From policy reforms to public opinion trends, it seems that the situation has changed faster, and in a more positive direction, on issues char- acterized as “transgender rights” than it has on those understood as “women’s rights.” This apparent gap may be exacerbated in the United States: at the con- clusion of the culture wars of the last forty years, the almost inseparable bond between movements for sexual and gender freedom that marked liberationist discourse of the 1970s has been torn asunder, reconstituted through the logic of an identity politics that affirms the demands for recognition of sexual and gender minorities but finds the misogyny that still structures all women’s lives largely unintelligible, outside the scope of the liberal project of inclusion. One poll, for example, found that 72 percent of the millennial generation in the United States favor laws banning discrimination against transgender people—a proportion very close to the 73 percent who support protections for gay and lesbian people. But only 55 percent of this generation, born between 1980 and 2000, say abortion should be legal in all (22 percent) or some (33 percent) cases (Jones and Cox 2015: 42, 3). In a three-month period ending July 31, 2015, when this introduction was written, the New York Times editorial board came out in support of transgender issues seven times—and that number does not include the several almost uni- versally positive op-ed contributions published during the same period. -

Transfeminism What the Trans Moment Has to Offer Radical Feminism

The TransAdvocate Series TransFeminism What the Trans Moment Has to Offer Radical Feminism (Part One) By John Stoltenberg @JohnStoltenberg I recently read an essay about men and rape, written from a radical feminist point of view, which included a particular statement that jumped out at me: Men’s intrusive and abusive sexual behaviors against women (as well as against girls, boys, and vulnerable men) are so woven into the everyday fabric of life in a patriarchal society that the intrusion and abuse is often invisible to men. What surprised me was not the author’s identification of the perpetrator class men. If we’re talking about rapists statistically, after all, we’re pretty much talking about people raised to be a man. And given the privileged insensitivity that men are entitled to in male supremacy, the author’s point about men’s obliviousness to the extent and harm of rape made self-evident sense as well. No, what struck me instead was the author’s earnest attempt (within careful parentheses) to describe the victim class inclusively. In discussions of most issues of urgent concern to radical feminism, this inclusivity very much needs to be referenced: Sex trafficking, sexual harassment, intimate partner violence—these abuses and more happen not only to cis women. And radical feminist insights about those abuses can benefit many other victimized populations. But to my mind, this is the point at which the author’s case fell short. For to describe accurately the class of potential and actual victims of rape would necessarily mean including people who are trans, nonbinary, gender nonconforming, intersex, and otherwise not specifically cisgender. -

Feminist Publishing

WOMEN'SSTUDIES LIBRARIAN The Un~versltyof W~sconsinSystem *:* *:* A OUARTERLY OF WOMEN'S STUDIES RESOURCES 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS FROMTHEEDITORS ........................................................1 BOOK REVIEWS SPECIAL CLUSTER ON WOMEN AND SPORT CONTROL OF WOMEN'S SPORTS: THE STRUGGLE ABOUT EQUALITY ....................1 by Julia Brown. BASKETBALLANDBRONCOS .........................................................4 by Susan Harman. WOMENAREGOODSPORTS ..........................................................6 by Jane Piliavin. PLAY BALL! AND THEY DON'T MEAN SOFTBALL. ......................................9 by Dorothy Steffens. ECOFEMINISM NORTH AND SOUTH ...................................................ll by Anne Statham. Ecofeminism by MariaMies andVandanaShiva;Ecofeminism:Women, Animals, Nature, ed. by Greta Gaard; Women, the Environment, and Development: Towards a Theoretical Synthesis by Rosi Braidotti et al. WOMEN'SPEACE-WORK .............................................................14 by Laura Roskos. Womenand Peace: Feminist Visions of Global Security by Betty A. Reardon;Peaceas a Women's Issue by Harriet Hyman Alonso; Women Strike for Peace: Traditional Motherhood and Radical Politics in the 1960s by Amy Swerdlow; and Gendering War Talk, ed. by Miriam Cooke and Angela Woollacott. 1 FEMINIST DOCUMENTATION CENTERS IN BOMBAY. ......................19 by Shelley Anderson FEMINIST PUBLISHING ....................................................20 A new feminist press, Virago celebrates twenty years, a report on the Sixth International -

Gender, Disability and Social Standing

Recognizing Social Subjects: Gender, Disability and Social Standing by Filipa Melo Lopes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Philosophy) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Ishani Maitra, Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Elizabeth S. Anderson Professor Derrick L. Darby Filipa Melo Lopes [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-8487-3161 © Filipa Melo Lopes 2019 Acknowledgements I want to thank everyone who supported and guided me through the various stages of this project. I am extremely grateful to my advisor Ishani Maitra for her extensive comments, thoughtful discussion of countless drafts and for her invaluable advice throughout these years. I am also very thankful for the support and guidance of my committee members Derrick Darby, Elizabeth Anderson and Paulina Alberto. Their feedback, their rich reading suggestions and their encouragement were extremely important. Sarah Buss read and discussed various pieces of this work with me and I am thankful for her support throughout my time at Michigan. It was a pleasure to work with Maria Lasonen-Aarnio and Janum Sethi, from whom I learned a great deal. I also want to thank Charlotte Witt and David Livingstone Smith for their inspiring work and for being so generous with their time and ideas. I benefited from extremely formative comments and challenges from interdisciplinary audiences who engaged with various parts of this project. I want to thank especially the fellows at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender during the Summer of 2017, and the fellows at the Institute for the Humanities during the academic year of 2017-2018. -

Not a Moral Issue*

Commentaries Not A Moral Issue* Catharine A. MacKinnon** Pornosec, the subsection of the Fiction Department which turned out cheap pornography for dittribution among the proles . nicknamed Muck House by the people who worked in it . .produce[di booklets in sealed packets with titles like Spanking Stories or One Night in a Girls' School, to be bought furtively by proletarian youths who were under the impression that they were buying something illegal. *** A critique of pornography' is to feminism what its defense is to male supremacy. Central to the institutionalization of male dominance, por- • Prior versions of this commentary were given as speeches to the Morality Colloquium, University of Minnesota, February 17, 1983; Women and the Law Conference, panel on pornography, April 4, 1983; and Conference on Media Violence and Pornography, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, February 3-5, 1984. The title of this article is a play on the title of the anti-pornography film by the Canadian Film Board, Not a Love Slog (1983). ** Associate Professor, University of Minnesota Law School; author of Sexual Harassment of Working Women. Professor MacKinnon, with Andrea Dworkin, conceived and wrote the civil rights anti-pornography ordinances passed by the Minneapolis and Indianapolis city councils. *** G. ORWELL, 1984, at 108-09 (1949). 1. This text as a whole is intended to communicate what I mean by pornography. The key work on the subject is A. DWORKIN, PORNOGRAPHY: MEN POSSESSING WOMEN (1981). No definition can convey the meaning of a word as well as its use in context can. However what Andrea Dworkin and I mean by pornography is rather well captured in our legal defini- tion of the term.