Not a Moral Issue*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pornography, Morality, and Harm: Why Miller Should Survive Lawrence

File: 02-DIONNE-Revised.doc Created on: 3/12/2008 1:29 PM Last Printed: 3/12/2008 1:34 PM 2008] 611 PORNOGRAPHY, MORALITY, AND HARM: WHY MILLER SHOULD SURVIVE LAWRENCE Elizabeth Harmer Dionne∗ INTRODUCTION In 2003, a divided Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas1 declared that morality, absent third-party harm, is an insufficient basis for criminal legis- lation that restricts private, consensual sexual conduct.2 In a strongly worded dissent, Justice Scalia declared that this “called into question” state laws against obscenity (among others), as such laws are “based on moral choices.”3 Justice Scalia does not specifically reference Miller v. Califor- nia,4 the last case in which the Supreme Court directly addressed the issue of whether the government may suppress obscenity. However, if, as Justice Scalia suggests, obscenity laws have their primary basis in private morality, the governing case that permits such laws must countenance such a moral basis. The logical conclusion is that Lawrence calls Miller, which provides the legal test for determining obscenity, into question.5 ∗ John M. Olin Fellow in Law, Harvard Law School. Wellesley College (B.A.), University of Cambridge (M. Phil., Marshall Scholar), Stanford Law School (J.D.). The author thanks Professors Frederick Schauer, Thomas Grey, and Daryl Levinson for their helpful comments on this Article. She also thanks the editorial staff of GEORGE MASON LAW REVIEW for their able assistance in bringing this Article to fruition. 1 539 U.S. 558 (2003). 2 Id. at 571 (“The issue is whether the majority may use the power of the state to enforce these views on the whole society through operation of the criminal law. -

Please Scroll Down for Article

This article was downloaded by: [University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Libraries] On: 1 February 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 792081565] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Communication Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713456253 Sexual Politics from Barnard to Las Vegas Barbara G. Brents a a Department of Sociology, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Online Publication Date: 01 July 2008 To cite this Article Brents, Barbara G.(2008)'Sexual Politics from Barnard to Las Vegas',The Communication Review,11:3,237 — 246 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/10714420802306593 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714420802306593 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2 Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Memorial for Shulamith Firestone St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, Parish Hall September 23, 2012 Program 4:00–6:00 pm Laya Firestone Seghi Eileen Myles Kathie Sarachild Jo Freeman Ti-Grace Atkinson Marisa Figueiredo Tributes from: Anne Koedt Peggy Dobbins Bev Grant singing May the Work That I Have Done Speak For Me Kate Millett Linda Klein Roxanne Dunbar Robert Roth 3 Open floor for remembrances Lori Hiris singing Hallelujah Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Reception 6:00–6:30 4 Shulamith Firestone Achievements & Education Writer: 1997 Published Airless Spaces. Semiotexte Press 1997. 1970–1993 Published The Dialectic of Sex, Wm. Morrow, 1970, Bantam paperback, 1971. – Translated into over a dozen languages, including Japanese. – Reprinted over a dozen times up through Quill trade edition, 1993. – Contributed to numerous anthologies here and abroad. Editor: Edited the first feminist magazine in the U.S.: 1968 Notes from the First Year: Women’s Liberation 1969 Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation 1970 Consulting Editor: Notes from the Third Year: WL Organizer: 1961–3 Activist in early Civil Rights Movement, notably St. Louis c.o.r.e. (Congress on Racial Equality) 1967–70 Founder-member of Women’s Liberation Movement, notably New York Radical Women, Redstockings, and New York Radical Feminists. Visual Artist: 1978–80 As an artist for the Cultural Council Foundation’s c.e.t.a. Artists’ Project (the first government funded arts project since w.p.a.): – Taught art workshops at Arthur Kill State Prison For Men – Designed and executed solo-outdoor mural on the Lower East Side for City Arts Workshop – As artist-in-residence at Tompkins Square branch of the New York Public Library, developed visual history of the East Village in a historical mural project. -

Rethinking Coalitions: Anti-Pornography Feminists, Conservatives, and Relationships Between Collaborative Adversarial Movements

Rethinking Coalitions: Anti-Pornography Feminists, Conservatives, and Relationships between Collaborative Adversarial Movements Nancy Whittier This research was partially supported by the Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences. The author thanks the following people for their comments: Martha Ackelsberg, Steven Boutcher, Kai Heidemann, Holly McCammon, Ziad Munson, Jo Reger, Marc Steinberg, Kim Voss, the anonymous reviewers for Social Problems, and editor Becky Pettit. A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2011 Annual Meetings of the American Sociological Association. Direct correspondence to Nancy Whittier, 10 Prospect St., Smith College, Northampton MA 01063. Email: [email protected]. 1 Abstract Social movements interact in a wide range of ways, yet we have only a few concepts for thinking about these interactions: coalition, spillover, and opposition. Many social movements interact with each other as neither coalition partners nor opposing movements. In this paper, I argue that we need to think more broadly and precisely about the relationships between movements and suggest a framework for conceptualizing non- coalitional interaction between movements. Although social movements scholars have not theorized such interactions, “strange bedfellows” are not uncommon. They differ from coalitions in form, dynamics, relationship to larger movements, and consequences. I first distinguish types of relationships between movements based on extent of interaction and ideological congruence and describe the relationship between collaborating, ideologically-opposed movements, which I call “collaborative adversarial relationships.” Second, I differentiate among the dimensions along which social movements may interact and outline the range of forms that collaborative adversarial relationships may take. Third, I theorize factors that influence collaborative adversarial relationships’ development over time, the effects on participants and consequences for larger movements, in contrast to coalitions. -

Women and Gender Studies / Queer Theory

1 Women and Gender Studies / Queer Theory Please choose at least 60 to 67 texts from across the fields presented. Students are expected to familiarize themselves with major works throughout this field, balancing their particular interests with the need to prepare themselves broadly in the topic. First Wave Feminism 1. Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) 2. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions” (1848) 3. Harriet Taylor, “Enfranchisement of Women” (1851) 4. Sojourner Truth, “Ain’t I a Woman?” (1851) 5. John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women (1869) 6. Susan B. Anthony, Speech after Arrest for Illegal Voting (1872) 7. Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice From the South (1892) 8. Charlotte Perkins, Women and Economics (1898) 9. Emma Goldman, The Traffic in Women and Other Essays on Feminism (1917) 10. Nancy Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (1987) 11. Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (1929) 12. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1953) Second Wave Feminism 13. Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (1963) 14. Kate Millet, Sexual Politics (1969) 15. Phyllis Chesler, Women and Madness (1970) 16. Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970) 17. Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch (1970) 18. Brownmiller, Susan, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975) 19. Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (1976) 20. Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism (1978) 21. 22. Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-75 (1989) Third Wave Feminism 23. Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake, eds., Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism (1997) 24. -

Book Review: Ratna Kapur's Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Postcolonialism London: Glasshouse, 2005

Book Review: Ratna Kapur's Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Postcolonialism London: GlassHouse, 2005. Pp. vi, 219. Ryan Charles Gagliot Nietzsche observed that the commonest stupidity consists of forgetting what one is trying to do.' As Ratna Kapur argues in Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Postcolonialism, political activism's continued reliance on liberal and Western feminist agendas evinces an absence of deep thinking, in turn unwittingly reinforcing the hegemony and subordination it means to challenge. In this collection of essays, Kapur draws from postcolonial feminist legal theory to critique the misguided causal logic of liberalism, which mistakenly assumes that "more rights lead to more freedom and greater equality." 2 Examining law and political activism, Kapur concludes that, unless modem postcolonial society is understood as the site of an historical, discursive struggle informed by the colonial past, steadfast allegiance to the rights project of liberalism risks perpetuating the subordination of oppressed subaltern groups under the illusive panacea of universal rights.3 Kapur uses her analysis of the condition of Indian women, transnational migrants, and sexual subalterns- groups marginally situated in and subordinate to hegemonic Indian culture-to interrogate the broader agenda of liberalism and Western feminism. This agenda ostensibly endeavors to protect third-world "victims," but, instead, Kapur argues, it tends to offer legal protection on terms that paradoxically reinforce normative and essentialist assumptions of gender, culture, and agency-thus perpetuating the very subordination and victimization it seeks to remedy. But Erotic Justice not only challenges the politics of liberalism and Western feminism by exposing the limitations of the rights project; Kapur's collection of essays goes a step further and asks what the basis of political activism should be without the comfort of liberalism's clear yet misguided Yale Law School, J.D. -

Susan Faludi How Shulamith Firestone Shaped Feminism The

AMERICAN CHRONICLES DEATH OF A REVOLUTIONARY Shulamith Firestone helped to create a new society. But she couldn’t live in it. by Susan Faludi APRIL 15, 2013 Print More Share Close Reddit Linked In Email StumbleUpon hen Shulamith Firestone’s body was found Wlate last August, in her studio apartment on the fifth floor of a tenement walkup on East Tenth Street, she had been dead for some days. She was sixtyseven, and she had battled schizophrenia for decades, surviving on public assistance. There was no food in the apartment, and one theory is that Firestone starved, though no autopsy was conducted, by preference of her Orthodox Jewish family. Such a solitary demise would have been unimaginable to anyone who knew Firestone in the late nineteensixties, when she was at the epicenter of the radicalfeminist movement, Firestone, top left, in 1970, at the beach, surrounded by some of the same women who, a reading “The Second Sex”; center left, with month after her death, gathered in St. Mark’s Gloria Steinem, in 2000; and bottom right, Church IntheBowery, to pay their respects. in 1997. Best known for her writings, Firestone also launched the first major The memorial service verged on radical radicalfeminist groups in the country, feminist revival. Women distributed flyers on which made headlines in the late nineteen consciousnessraising, and displayed copies of sixties and early seventies with confrontational protests and street theatre. texts published by the Redstockings, a New York group that Firestone cofounded. The WBAI radio host Fran Luck called for the Tenth Street studio to be named the Shulamith Firestone Memorial Apartment, and rented “in perpetuity” to “an older and meaningful feminist.” Kathie Sarachild, who had pioneered consciousnessraising and coined the slogan “Sisterhood Is Powerful,” in 1968, proposed convening a Shulamith Firestone Women’s Liberation Memorial Conference on What Is to Be Done. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

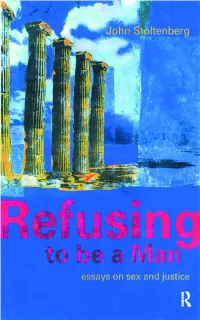

Refusing to Be a Man

REFUSING TO BE A MAN Since its original publication in 1989, Refusing to Be a Man has been acclaimed as a classic and widely cited in gender studies literature. In thirteen eloquent essays, Stoltenberg articulates the first fully argued liberation theory for men that will also liberate women. He argues that male sexual identity is entirely a political and ethical construction whose advantages grow out of injustice. His thesis is, however, ultimately one of hope—that precisely because masculinity is so constructed, it is possible to refuse it, to act against it, and to change. A new introduction by the author discusses the roots of his work in the American civil rights and radical feminist movements and distinguishes it from the anti-feminist philosophies underlying the recent tide of reactionary men’s movements. John Stoltenberg is the radical feminist author of The End of Manhood: Parables on Sex and Selfhood (rev. edn, London and New York: UCL Press, 2000) and What Makes Pornography “Sexy” ? (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, 1994). He is cofounder of Men Against Pornography. REFUSING TO BE A MAN Essays on Sex and Justice Revised Edition JOHN STOLTENBERG London First published 1989 by Breitenbush Books, Inc. Revised edition published 2000 in the UK and the USA by UCL Press 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE The name of University College London (UCL) is a registered trade mark used by UCL Press with the consent of the owner. UCL Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Geoffrey Charles BOWKER Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences University of California, Irvine 6210 Donald Bren Hall Irvine, CA 92697-3425 [email protected] http://www.sis.pitt.edu/~gbowker POSITIONS Professor, Director Values in Design Laboratory, School of Information and Computer Science, University of California at Irvine, 2012+ Professor and Senior Scholar in Cyberscholarship, School of Information Sciences, University of Pittsburgh. 2009-2011 Executive Director, Regis and Dianne McKenna Professor, Center for Science, Technology and Society, Santa Clara University. Professor in Communication and Environmental Studies. 2005-2009 Chair, Department of Communicaton, University of California, San Diego, 2002-2004. Professor, Department of Communication, University of California, San Diego, 1999+. Teaching ethnography of information systems, computing and communication. Research project in biodiversity informatics. Participating Faculty, Interdisciplinary PhD Program in Cognitive Science, UCSD, 2001+. Fellow, San Diego Supercomputer Center, 2000+. Adjunct Professor, Department of History, University of California, San Diego, 1999+. Zero time appointment. Faculty Affiliate, National Center for Supercomputing Applications, 1998-1999. Assistant then Associate Professor, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, University of Illinois at Urbana/Champaign, 1993-1998. Teaching information resources management, research methodologies in information science, information systems analysis and management. Research projects in history and sociology of the International Classification of Diseases, the Nursing Interventions Classification and organizational memory. (Promoted to Associate Fall 1996). May - June 1994 Visiting Professor, Department of Computer Science, Aarhuis University, Denmark. Teaching course in computer supported cooperative work and the ethnography of information systems. Visiting Scholar, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, University of Illinois at Urbana/Champaign. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL How to cite: MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL (2014) Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10818/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 “Not Andrea”: The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin Submitted for the degree of Masters by Research in English Literature By Isobel MacBrayne 1 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 4 Chapter I – Re-assessing the Feminist Polemic and its Relation to Fiction 10 Chapter II – Intertextuality in Dworkin’s Fiction 32 Chapter III – The construction of Dworkin and Her Media Representation 65 Conclusion 97 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Durham University for giving me this opportunity, the staff of the English Department, and all the admin and library staff whose time and hard work too often goes unnoticed.