Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pornography, Morality, and Harm: Why Miller Should Survive Lawrence

File: 02-DIONNE-Revised.doc Created on: 3/12/2008 1:29 PM Last Printed: 3/12/2008 1:34 PM 2008] 611 PORNOGRAPHY, MORALITY, AND HARM: WHY MILLER SHOULD SURVIVE LAWRENCE Elizabeth Harmer Dionne∗ INTRODUCTION In 2003, a divided Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas1 declared that morality, absent third-party harm, is an insufficient basis for criminal legis- lation that restricts private, consensual sexual conduct.2 In a strongly worded dissent, Justice Scalia declared that this “called into question” state laws against obscenity (among others), as such laws are “based on moral choices.”3 Justice Scalia does not specifically reference Miller v. Califor- nia,4 the last case in which the Supreme Court directly addressed the issue of whether the government may suppress obscenity. However, if, as Justice Scalia suggests, obscenity laws have their primary basis in private morality, the governing case that permits such laws must countenance such a moral basis. The logical conclusion is that Lawrence calls Miller, which provides the legal test for determining obscenity, into question.5 ∗ John M. Olin Fellow in Law, Harvard Law School. Wellesley College (B.A.), University of Cambridge (M. Phil., Marshall Scholar), Stanford Law School (J.D.). The author thanks Professors Frederick Schauer, Thomas Grey, and Daryl Levinson for their helpful comments on this Article. She also thanks the editorial staff of GEORGE MASON LAW REVIEW for their able assistance in bringing this Article to fruition. 1 539 U.S. 558 (2003). 2 Id. at 571 (“The issue is whether the majority may use the power of the state to enforce these views on the whole society through operation of the criminal law. -

The Radical Feminist Manifesto As Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, and Second Wave Resistance

Southern Journal of Communication ISSN: 1041-794X (Print) 1930-3203 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsjc20 The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance Kimber Charles Pearce To cite this article: Kimber Charles Pearce (1999) The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance, Southern Journal of Communication, 64:4, 307-315, DOI: 10.1080/10417949909373145 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949909373145 Published online: 01 Apr 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 578 View related articles Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsjc20 The Radical Feminist Manifesto as Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, And Second Wave Resistance Kimber Charles Pearce n June of 1968, self-styled feminist revolutionary Valerie Solanis discovered herself at the heart of a media spectacle after she shot pop artist Andy Warhol, whom she I accused of plagiarizing her ideas. While incarcerated for the attack, she penned the "S.C.U.M. Manifesto"—"The Society for Cutting Up Men." By doing so, Solanis appropriated the traditionally masculine manifesto genre, which had evolved from sov- ereign proclamations of the 1600s into a form of radical protest of the 1960s. Feminist appropriation of the manifesto genre can be traced as far back as the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, at which suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin, and Mary Ann McClintock parodied the Declara- tion of Independence with their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Campbell, 1989). -

Beyond Trashiness: the Sexual Language of 1970S Feminist Fiction

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 4 Issue 2 Harvesting our Strengths: Third Wave Article 2 Feminism and Women’s Studies Apr-2003 Beyond Trashiness: The exS ual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction Meryl Altman Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Altman, Meryl (2003). Beyond Trashiness: The exS ual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction. Journal of International Women's Studies, 4(2), 7-19. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol4/iss2/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2003 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Beyond Trashiness: The Sexual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction By Meryl Altmani Abstract It is now commonplace to study the beginning of second wave US radical feminism as the history of a few important groups – mostly located in New York, Boston and Chicago – and the canon of a few influential polemical texts and anthologies. But how did feminism become a mass movement? To answer this question, we need to look also to popular mass-market forms that may have been less ideologically “pure” but that nonetheless carried the edge of feminist revolutionary thought into millions of homes. This article examines novels by Alix Kates Shulman, Marge Piercy and Erica Jong, all published in the early 1970s. -

The Grand Experiment of Sisterhood Is Powerful by Jennifer Gilley Robin

“This Book Is An Action”: The Grand Experiment of Sisterhood is Powerful By Jennifer Gilley This paper was presented as part of "A Revolutionary Moment: Women's Liberation in the late 1960s and early 1970s," a conference organized by the Women's, Gender, & Sexuality Studies Program at Boston University, March 27-29, 2014. This paper was part of the panel titled “Women Revolt: Publishing Feminists, Publishing Feminisms.” Robin Morgan’s 1970 anthology Sisterhood is Powerful (SIP) was a landmark work of the second wave feminist movement and a major popularizer of radical feminism outside the limited scope of urban-based women’s liberation groups. As Morgan notes in her memoir, it became “the ‘click,’ the first feminist epiphany for hundreds of thousands of women, and the staple of mushrooming women’s studies courses around the world.”1 Indeed, the New York Public Library picked SIP as one of its Books of the Century, one of 11 books listed under the heading “Women Rise.” As an anthology of radical feminist essays, some of which had already been published as pamphlets or by the movement press, SIP’s purpose was to collect in one place the diverse voices of women’s liberation to enable distribution, and thus radicalization, on a massive scale. Morgan achieved this purpose by publishing her collection with Random House, who had the marketing and distribution reach to get copies into every supermarket in America, but radical feminism and Random House made strange bedfellows to say the least. Random House was the very figurehead of what June Arnold would later call “the finishing press” (because it is out to finish our movement) and Carol Seajay would dub LICE, or the Literary Industrial Corporate Establishment. -

Excerpt from “Outlaw Woman: a Memoir of the War Years 1960-1975”

1 Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz Excerpt from Chapter 4: 1968 pp. 109-156) of Outlaw Woman: A Memoir of the War Years, 1960-1975, (New edition, University of Oklahoma Press, 2014) Presented as part of "A Revolutionary Moment: Women's Liberation in the late 1960s and early 1970s," a conference organized by the Women's, Gender, & Sexuality Studies Program at Boston University, March 27-29, 2014. “SUPER-WOMAN POWER ADVOCATE SHOOTS . .” That news headline propelled me to action. On Tuesday, June 4, 1968, I sat in Sanborn’s restaurant in México City across from the beautiful Bellas Artes building. As the original Sanborn's, the walls are lined with sepia photographs of Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa and their soldiers celebrating their revolutionary victory in that very place in 1914. Jean-Louis wanted me to meet his old friend Arturo. Arturo was a Mexican poet and anarchist intensively involved in organizing against the Olympics. I was sullen and angry because Jean-Louis had introduced me as mi esposa, his wife. Screaming fights between us had become normal, and I was trying to devise another way to go to Cuba. I suspected that the purpose of the meeting with Arturo was to dissuade me from going to Cuba. Arturo called Fidel Castro a statist who was wedded to 2 “Soviet imperialism,” and he complained that Cuba had agreed to participate in the Olympics. Arturo was smart, intense, and angry, his personality similar to that of Jean-Louis. When he spoke, he hit the palm of his left hand with the rolled-up tabloid in his right hand. -

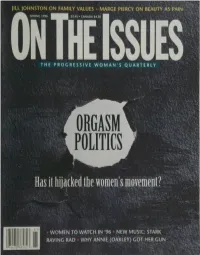

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2 Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Memorial for Shulamith Firestone St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, Parish Hall September 23, 2012 Program 4:00–6:00 pm Laya Firestone Seghi Eileen Myles Kathie Sarachild Jo Freeman Ti-Grace Atkinson Marisa Figueiredo Tributes from: Anne Koedt Peggy Dobbins Bev Grant singing May the Work That I Have Done Speak For Me Kate Millett Linda Klein Roxanne Dunbar Robert Roth 3 Open floor for remembrances Lori Hiris singing Hallelujah Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Reception 6:00–6:30 4 Shulamith Firestone Achievements & Education Writer: 1997 Published Airless Spaces. Semiotexte Press 1997. 1970–1993 Published The Dialectic of Sex, Wm. Morrow, 1970, Bantam paperback, 1971. – Translated into over a dozen languages, including Japanese. – Reprinted over a dozen times up through Quill trade edition, 1993. – Contributed to numerous anthologies here and abroad. Editor: Edited the first feminist magazine in the U.S.: 1968 Notes from the First Year: Women’s Liberation 1969 Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation 1970 Consulting Editor: Notes from the Third Year: WL Organizer: 1961–3 Activist in early Civil Rights Movement, notably St. Louis c.o.r.e. (Congress on Racial Equality) 1967–70 Founder-member of Women’s Liberation Movement, notably New York Radical Women, Redstockings, and New York Radical Feminists. Visual Artist: 1978–80 As an artist for the Cultural Council Foundation’s c.e.t.a. Artists’ Project (the first government funded arts project since w.p.a.): – Taught art workshops at Arthur Kill State Prison For Men – Designed and executed solo-outdoor mural on the Lower East Side for City Arts Workshop – As artist-in-residence at Tompkins Square branch of the New York Public Library, developed visual history of the East Village in a historical mural project. -

Rethinking Coalitions: Anti-Pornography Feminists, Conservatives, and Relationships Between Collaborative Adversarial Movements

Rethinking Coalitions: Anti-Pornography Feminists, Conservatives, and Relationships between Collaborative Adversarial Movements Nancy Whittier This research was partially supported by the Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences. The author thanks the following people for their comments: Martha Ackelsberg, Steven Boutcher, Kai Heidemann, Holly McCammon, Ziad Munson, Jo Reger, Marc Steinberg, Kim Voss, the anonymous reviewers for Social Problems, and editor Becky Pettit. A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2011 Annual Meetings of the American Sociological Association. Direct correspondence to Nancy Whittier, 10 Prospect St., Smith College, Northampton MA 01063. Email: [email protected]. 1 Abstract Social movements interact in a wide range of ways, yet we have only a few concepts for thinking about these interactions: coalition, spillover, and opposition. Many social movements interact with each other as neither coalition partners nor opposing movements. In this paper, I argue that we need to think more broadly and precisely about the relationships between movements and suggest a framework for conceptualizing non- coalitional interaction between movements. Although social movements scholars have not theorized such interactions, “strange bedfellows” are not uncommon. They differ from coalitions in form, dynamics, relationship to larger movements, and consequences. I first distinguish types of relationships between movements based on extent of interaction and ideological congruence and describe the relationship between collaborating, ideologically-opposed movements, which I call “collaborative adversarial relationships.” Second, I differentiate among the dimensions along which social movements may interact and outline the range of forms that collaborative adversarial relationships may take. Third, I theorize factors that influence collaborative adversarial relationships’ development over time, the effects on participants and consequences for larger movements, in contrast to coalitions. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

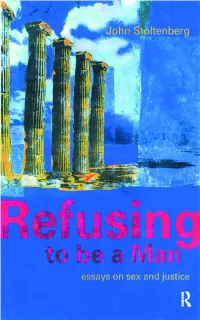

Refusing to Be a Man

REFUSING TO BE A MAN Since its original publication in 1989, Refusing to Be a Man has been acclaimed as a classic and widely cited in gender studies literature. In thirteen eloquent essays, Stoltenberg articulates the first fully argued liberation theory for men that will also liberate women. He argues that male sexual identity is entirely a political and ethical construction whose advantages grow out of injustice. His thesis is, however, ultimately one of hope—that precisely because masculinity is so constructed, it is possible to refuse it, to act against it, and to change. A new introduction by the author discusses the roots of his work in the American civil rights and radical feminist movements and distinguishes it from the anti-feminist philosophies underlying the recent tide of reactionary men’s movements. John Stoltenberg is the radical feminist author of The End of Manhood: Parables on Sex and Selfhood (rev. edn, London and New York: UCL Press, 2000) and What Makes Pornography “Sexy” ? (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, 1994). He is cofounder of Men Against Pornography. REFUSING TO BE A MAN Essays on Sex and Justice Revised Edition JOHN STOLTENBERG London First published 1989 by Breitenbush Books, Inc. Revised edition published 2000 in the UK and the USA by UCL Press 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE The name of University College London (UCL) is a registered trade mark used by UCL Press with the consent of the owner. UCL Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

A Study of the Weathermen, Radical Feminism and the New Left

Exploring Women’s Complex Relationship with Political Violence: A Study of the Weathermen, Radical Feminism and the New Left by Lindsey Blake Churchill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Marilyn Myerson, Ph.D. Ruth Banes, Ph.D. Sara Crawley, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 1, 2005 Keywords: revolution, weather underground, valerie solanas, robin morgan, jane alpert, gilda zwerman, ti-grace atkinson, bernadine dohrn © Copyright 2005, Lindsey Blake Churchill Table of Contents Abstract ii Introduction 1 Chapter One: SDS 7 The Explosive Convention 11 Wannabe Revolutionaries 18 Chapter Two: Feminism’s Critique 24 Radical-Cultural Feminism 30 Pacifist Feminists 33 Chapter Three: Violent Feminists 35 Female Terrorists 42 Chapter Four: Conclusion 52 References 54 i Exploring Women’s Complex Relationship with Violence: A Study of the Weathermen, Radical Feminism and the New Left Lindsey Blake Churchill ABSTRACT In this thesis I use the radical, pro-violent organization the Weathermen as a framework to examine women and feminism’s complex relationships with violence. My thesis attempts to show the many belief systems that second wave feminists possessed concerning the role(s) of women and violence in revolutionary organizations. Hence, by using the Weathermen as a framework, I discuss various feminist essentialist and pacifist critiques of violence. I also include an analysis of feminists who, similar to the Weathermen, embraced political violence. For example, radical feminists Robin Morgan and Jane Alpert criticized the Weathermen’s violent tactics while other feminists such as Ti-Grace Atkinson and Valerie Solanas advocated that women “pick up the gun” in order to destroy patriarchal society. -

A Good Wife Always Knows Her Place?

Fabrizio 1 Jonnie Fabrizio English 259 Dr. Jill Swiencicki 12 April 2011 A Good Wife Always Knows Her Place? In the late 1960s to early 1970s, a new movement of feminism emerged in America. Second wave feminism perhaps began in response to the 1950’s housewife stereotype that many women were trying to conform to. Up until 1980, the “head of the household” according to the U.S. Census needed to be a male (Baumgardner 331). In the 1950’s, women were subjected to media, advertisements, and society to become the “ideal” housewife. The following is an example of a spread used to stereotypically describe the role of a housewife in a Housekeeping Monthly magazine from 1955: Fabrizio 2 This type of woman was encouraged to become dedicated to household work and activities centered on her spouse and family. The exigency for this feminist movement was due to the frustrated at this subordination of women. Activists of second wave feminism took charge. This form of feminism urged women to embrace their gender identity, and become independent from the male sex. It also insisted that women should be treated equally to men. The roles of women were about to change. Groups such as the National Organization of Women (NOW) used tactics such as holding a “Rights Not Roses” event on Mother’s Day. The goal of this event was to show the nation that women should be freely accepted in the workplace, as well as having equal rights to men. On this day, many women dumped piles of aprons on the White House’s lawn.