Pornography, Morality, and Harm: Why Miller Should Survive Lawrence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexo, Amor Y Cine Por Salvador Sainz Introducción

Sexo, amor y cine por Salvador Sainz Introducción: En la última secuencia de El dormilón (The Sleeper, 1973), Woody Allen, desengañado por la evolución polí tica de una hipotética sociedad futura, le decí a escéptico a Diane Keaton: “Yo sólo creo en el sexo y en la muerte” . Evidentemente la desconcertante evolución social y polí tica de la última década del siglo XX parecen confirmar tal aseveración. Todos los principios é ticos del filósofo alemá n Hegel (1770-1831) que a lo largo de un siglo engendraron movimientos tan dispares como el anarquismo libertario, el comunismo autoritario y el fascismo se han desmoronado como un juego de naipes dejando un importante vací o ideológico que ha sumido en el estupor colectivo a nuestra desorientada generación. Si el siglo XIX fue el siglo de las esperanzas el XX ha sido el de los desengaños. Las creencias má s firmes y má s sólidas se han hundido en su propia rigidez. Por otra parte la serie interminable de crisis económica, polí tica y social de nuestra civilización parece no tener fin. Ante tanta decepción sólo dos principios han permanecido inalterables: el amor y la muerte. Eros y Tá natos, los polos opuestos de un mundo cada vez má s neurótico y vací o. De Tánatos tenemos sobrados ejemplos a cada cual má s siniestro: odio, intolerancia, guerras civiles, nacionalismo exacerbado, xenofobia, racismo, conservadurismo a ultranza, intransigencia, fanatismo… El Sé ptimo Arte ha captado esa evolución social con unas pelí culas cada vez má s violentas, con espectaculares efectos especiales que no nos dejan perder detalle de los aspectos má s sombrí os de nuestro entorno. -

We Control It on Our End, and Now It's up to You" -- Exploitation, Empowerment, and Ethical Portrayals of the Pornography Industry Julie E

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2017 "We control it on our end, and now it's up to you" -- Exploitation, Empowerment, and Ethical Portrayals of the Pornography Industry Julie E. Davin Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Davin, Julie E., ""We control it on our end, and now it's up to you" -- Exploitation, Empowerment, and Ethical Portrayals of the Pornography Industry" (2017). Student Publications. 543. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/543 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "We control it on our end, and now it's up to you" -- Exploitation, Empowerment, and Ethical Portrayals of the Pornography Industry Abstract Documentaries about pornography are beginning to constitute an entirely new subgenre of film. Big Hollywood names like James Franco and Rashida Jones are jumping on the bandwagon, using their influence and resources to invest in a type of audiovisual knowledge production far less mainstream than that in which they usually participate. The films that have resulted from this new movement are undoubtedly persuasive, no matter which side of the debate over pornography these directors have respectively chosen to represent. Moreover, regardless of the side(s) that audience members may have taken in the so-called “feminist porn debates,” one cannot ignore the rhetorical strength of the arguments presented in a wide variety of documentaries about pornography. -

Cutting Iip the S Picket Penaltk

BCGEU BACKED BY CLASSROOM SHUTDOWN VOL. 1, NO. 4/WEDNESDAY, NOV. 9, 1983 STRIKE TWO TEACHERS OUT: IT'S A WHOLE NEW BALL GAME! (PAGE 3) CUTTING IIP THE S PAGE 5 PICKET PENALTK PAGE 3 BEV DAVIES fn.jT.-. Second-Class Mall Bulk. 3rd Class Registration Pending Vancouver, B.C. No. 5136 TIMES, WEDNESDAY, NOV. 9, 1983 the right-wing legislative them, and went on to warn package introduced by Ben• school districts that shutting nett's Social Credit govern• down in the event of a ment last July. If the govern• 1 teachers' strike could result in ment workers' dispute wasn't board members being charged settled by Tuesday, Nov. 8, it with breaking the law. B.C. would trigger "phase two" of 3111:11 Teachers Federation president Solidarity's protest: BCGEU Larry Kuehn was not in• members would be joined by timidated. He called Count• teachers, crown corporation Heinrich's position workers, civic employees, bus iitll "ridiculous," accused the drivers and hospital workers in •ill! minister of "playing games" escalating waves. But it all and suggested the war of down to depended on the premier. As words would only anger Province political columnist teachers. Allen Garr put it: "What we Thursday, Nov. 3: Nor was Phase 2 are experiencing, of course, is Operation Solidarity, the trade the latest example of the union segment of the coali• By Stan Persky premier's crisis-management tion, terrified by Heinrich. With less than one shift to style. First he creates the crisis After an emergency session, go before the B.C. -

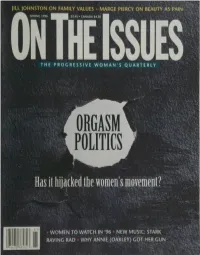

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Facts and Figures | Stop Porn Culture 28/03/2014

Facts and Figures | Stop Porn Culture 28/03/2014 Stop Porn Culture dedicated to challenging the porn industry and the harmful culture it perpetuates Home Aboutt Acttiion Allertts Eventts Resources GAIL DINES • SPC EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS • PRESS • CONTACT US • VOLUNTEERS SIGN-UP • Facts and Figures Our Culture is Porn Culture (U.S. and International Figures) There are over 68 million daily searches for pornography in the United States. Thats 25% of all daily searches (IFR, 2006). The sex industry is largest and most profitable industry in the world. “It includes street prostitution, brothels, ‘massage parlors’, strip clubs, human trafficking for sexual purposes, phone sex, child and adult pornography, mail order brides and sex tourism – just to mention a few of the most common examples.” (Andersson et al, 2013) In 2010, 13% of global web searches were for sexual content. This does not include P2P downloads and torrents. (Ogas & Gaddam) Pornhub receives over 1.68 million visits per hour. (Pornhub, 2013) Globally, teen is the most searched term. A Google Trends analysis indicates that searches for “Teen Porn” have more than tripled between 2005-2013, and teen porn was the fastest-growing genre over this period. Total searches for teen-related porn reached an estimated 500,000 daily in March 2013, far larger than other genres, representing approximately one-third of total daily searches for pornographic web sites. (Dines, 2013) The United States is the top producer of pornographic dvds and web material; the second largest is Germany: they each produce in excess of 400 porn films for dvd every week. Internet porn in the UK receives more traffic than social networks, shopping, news and media, email, finance, gaming and travel. -

Prostitution, Trafficking, and Cultural Amnesia: What We Must Not Know in Order to Keep the Business of Sexual Exploitation Running Smoothly

Prostitution, Trafficking, and Cultural Amnesia: What We Must Not Know in Order To Keep the Business of Sexual Exploitation Running Smoothly Melissa Farleyt INTRODUCTION "Wise governments," an editor in the Economist opined, "will accept that. paid sex is ineradicable, and concentrate on keeping the business clean, safe and inconspicuous."' That third adjective, "inconspicuous," and its relation to keeping prostitution "ineradicable," is the focus of this Article. Why should the sex business be invisible? What is it about the sex industry that makes most people want to look away, to pretend that it is not really as bad as we know it is? What motivates politicians to do what they can to hide it while at the same time ensuring that it runs smoothly? What is the connection between not seeing prostitution and keeping it in existence? There is an economic motive to hiding the violence in prostitution and trafficking. Although other types of gender-based violence such as incest, rape, and wife beating are similarly hidden and their prevalence denied, they are not sources of mass revenue. Prostitution is sexual violence that results in massive tMelissa Farley is a research and clinical psychologist at Prostitution Research & Education, a San Francisco non-profit organization, She is availabe at [email protected]. She edited Prostitution, Trafficking, and Traumatic Stress in 2003, which contains contributions from important voices in the field, and she has authored or contributed to twenty-five peer-reviewed articles. Farley is currently engaged in a series of cross-cultural studies on men who buy women in prostitution, and she is also helping to produce an art exhibition that will help shift the ways that people see prostitution, pornography, and sex trafficking. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

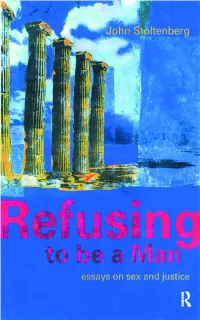

Refusing to Be a Man

REFUSING TO BE A MAN Since its original publication in 1989, Refusing to Be a Man has been acclaimed as a classic and widely cited in gender studies literature. In thirteen eloquent essays, Stoltenberg articulates the first fully argued liberation theory for men that will also liberate women. He argues that male sexual identity is entirely a political and ethical construction whose advantages grow out of injustice. His thesis is, however, ultimately one of hope—that precisely because masculinity is so constructed, it is possible to refuse it, to act against it, and to change. A new introduction by the author discusses the roots of his work in the American civil rights and radical feminist movements and distinguishes it from the anti-feminist philosophies underlying the recent tide of reactionary men’s movements. John Stoltenberg is the radical feminist author of The End of Manhood: Parables on Sex and Selfhood (rev. edn, London and New York: UCL Press, 2000) and What Makes Pornography “Sexy” ? (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, 1994). He is cofounder of Men Against Pornography. REFUSING TO BE A MAN Essays on Sex and Justice Revised Edition JOHN STOLTENBERG London First published 1989 by Breitenbush Books, Inc. Revised edition published 2000 in the UK and the USA by UCL Press 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE The name of University College London (UCL) is a registered trade mark used by UCL Press with the consent of the owner. UCL Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL How to cite: MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL (2014) Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10818/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 “Not Andrea”: The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin Submitted for the degree of Masters by Research in English Literature By Isobel MacBrayne 1 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 4 Chapter I – Re-assessing the Feminist Polemic and its Relation to Fiction 10 Chapter II – Intertextuality in Dworkin’s Fiction 32 Chapter III – The construction of Dworkin and Her Media Representation 65 Conclusion 97 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Durham University for giving me this opportunity, the staff of the English Department, and all the admin and library staff whose time and hard work too often goes unnoticed. -

Mord På En Playmate

ringer på. Holdningen i de enkelte filmanmeldelser spænder fra nøgtem-kritisk og distanceret til engageret-kritisk og personlig. Førstnævnte kan eksempelvis ses i »Jyllands MORD posten«, i Ib Montys anmeldelser som i afdæmpet fortælle stil, enkel kompositionsform og med klart tilkendegivne vurderinger giver læseren et luftfoto-overblik over filmene. Sidstnævnte kan f.eks. findes hos »Information«s Morten PÅ EN Piil, som i en tæt og sammenvævet fremstillingsform fortol ker dybere sammenhænge og betydningslag i filmene og gi ver et nærbilledindtryk af dem. I modtagelsen af »Isfugle« ses den sagligt-analytiske anmeldelse i aviser som »Berling- PLAYMATE ske Tidende« og »Information«. Michael Blædels anmeldelse i »Berlingske Tidende« star ter kontant og fængende: Et billede af isfugles adfærd og et KAARE SCHMIDT OM »STAR 80« replikeksempel karakteriserer filmens tema for læseren. Herefter følger et tematisk samlende, konkret referat, et af snit med en analytisk baseret karakteristik og fortolkning og endelig en vurderende detailbehandling i anmeldelsens sid ste afsnit. Iagttagelser gøres konkrete. F.eks. underbygges det synspunkt i anmeldelsen, at René-figuren for meget kommer til at fremstå som »skæbne i et fatalistisk spil« med et kritisk eksempel: »F.eks. viger filmen uforpligtende uden om det træk af psykopati, der også synes at være en af dæmonerne i Renés psyke«. Den differentierede og overve jende positive vurdering er bygget tæt ind i den løbende tekst, hvilket gør anmeldelsen kritisk orienterende frem for egentlig dømmende. Det ligger hos læseren selv at overveje om filmen skal ses. Anmelderens personlige oplevelse er trukket tilbage og giver plads for en nøgtem-kritisk hold ning i objektiv form. -

Can Pornography Ever Be Feminist?’

Amarpreet Kaur Intimate and Sexual Practices ‘Can pornography ever be feminist?’ Pornography is defined as ‘printed or visual material containing the explicit description or display of sexual organs or activity, intended to stimulate sexual excitement’ (Oxford Dictionaries, 2015). Reporting on 2014 activity, the self- acclaimed number one porn site named ‘Pornhub’ revealed that it had averaged about 5,800 visits per second (Pornhub, 2015a) throughout the year, making it one of the most globally popular websites and highlights how significantly dominant the online porn industry is. Those advocating for women’s equal footing in a patriarchal society, i.e. feminists, began occupying themselves with the porn industry in the 1970s (Ciclitira, 2004). Feminist literature is rife with anti-pornography stances focusing on male oppression of women, exploitation and violence (Russell, 1993) however it is also argued that pornography can be liberating and holds multiple benefits for women. Taking this in to consideration, the following assignment will explore whether or not pornography has the potential to ever give women an equal footing and satisfaction within digital society. Whilst many anti-porn feminists such as Gail Dines (2010), claim that porn is damaging to the female’s ideology on her body and sexuality, other feminists, like Wendy McElroy (1995) argue that pornography is actually liberating to women, their bodies and sexualities. Dines (TED X Talks, 2015) maintains porn advocates a blonde, white, well-toned woman, neglecting to mention that mainstream porn sites such as Pornhub feature categories such as ‘BBW’, which is an abbreviation for Big Beautiful Women (Rockson, 2009) and additional categories signify an interest in women of other races and with a range of hair colours. -

Pornography: Is It a Victimless Crime? Bill Muehlenberg, Family Council of Victoria February 2016 10,316 Words

Submission No 10 SEXUALISATION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE Organisation: Family Council of Victoria Name: Mr Bill Muehlenberg Date Received: 3/02/2016 Pornography: Is It a Victimless Crime? Bill Muehlenberg, Family Council of Victoria February 2016 10,316 words Pornography is of course big business. Exact estimates are hard to come by, but one recent guestimate put the porn industry at between $8 billion and $15 billion.1 That is a lot of money. But is it all just harmless fun? Is it just “a victimless crime”? Is it up to the adult to decide what he reads and views? These ideas have of course become part of the established wisdom. As Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister once said, “If you tell any lie long enough, often enough, and loud enough, people will come to believe it.” But is it really victimless? Is it just something that is done in private with no ill social consequences? The truth is, pornography is a very damaging. There are many problems associated with it. This paper will explore some of those problems, and seek to counter the pro-porn propaganda. It will also examine the very real harm children especially experience at the hands of porn. The harm porn produces At the very moment I have been working on this paper, a newspaper headline caught my attention: “Rapist Samuel Aldrich attacked schoolgirl after watching ‘sleeping girl’ porn”. The newspaper article opens as follows: A young man broke into a 16-year-old schoolgirl’s bedroom and raped her after taking photos of her home and watching pornography about sleeping girls.