Gender, Disability and Social Standing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pornography, Morality, and Harm: Why Miller Should Survive Lawrence

File: 02-DIONNE-Revised.doc Created on: 3/12/2008 1:29 PM Last Printed: 3/12/2008 1:34 PM 2008] 611 PORNOGRAPHY, MORALITY, AND HARM: WHY MILLER SHOULD SURVIVE LAWRENCE Elizabeth Harmer Dionne∗ INTRODUCTION In 2003, a divided Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas1 declared that morality, absent third-party harm, is an insufficient basis for criminal legis- lation that restricts private, consensual sexual conduct.2 In a strongly worded dissent, Justice Scalia declared that this “called into question” state laws against obscenity (among others), as such laws are “based on moral choices.”3 Justice Scalia does not specifically reference Miller v. Califor- nia,4 the last case in which the Supreme Court directly addressed the issue of whether the government may suppress obscenity. However, if, as Justice Scalia suggests, obscenity laws have their primary basis in private morality, the governing case that permits such laws must countenance such a moral basis. The logical conclusion is that Lawrence calls Miller, which provides the legal test for determining obscenity, into question.5 ∗ John M. Olin Fellow in Law, Harvard Law School. Wellesley College (B.A.), University of Cambridge (M. Phil., Marshall Scholar), Stanford Law School (J.D.). The author thanks Professors Frederick Schauer, Thomas Grey, and Daryl Levinson for their helpful comments on this Article. She also thanks the editorial staff of GEORGE MASON LAW REVIEW for their able assistance in bringing this Article to fruition. 1 539 U.S. 558 (2003). 2 Id. at 571 (“The issue is whether the majority may use the power of the state to enforce these views on the whole society through operation of the criminal law. -

Experiences of Transgender Men Who Joined National Pan-Hellenic Council Sororities Pre- Transition" (2020)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School November 2020 Experiences of Transgender Men Who Joined National Pan- Hellenic Council Sororities Pre-Transition Sydney Epps Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Educational Sociology Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Organization Development Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Epps, Sydney, "Experiences of Transgender Men Who Joined National Pan-Hellenic Council Sororities Pre- Transition" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5425. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5425 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. EXPERIENCES OF TRANSGENDER MEN WHO JOINED NATIONAL PAN-HELLENIC COUNCIL SORORITIES PRE- TRANSITION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Education by Sydney A. Yvonne Epps B.A. Ohio University, 2012 B.S. Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Embry-Riddle -

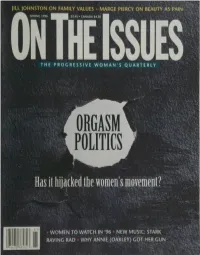

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

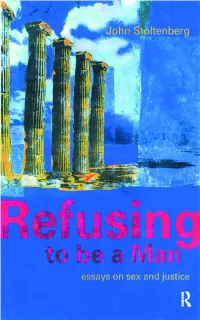

Refusing to Be a Man

REFUSING TO BE A MAN Since its original publication in 1989, Refusing to Be a Man has been acclaimed as a classic and widely cited in gender studies literature. In thirteen eloquent essays, Stoltenberg articulates the first fully argued liberation theory for men that will also liberate women. He argues that male sexual identity is entirely a political and ethical construction whose advantages grow out of injustice. His thesis is, however, ultimately one of hope—that precisely because masculinity is so constructed, it is possible to refuse it, to act against it, and to change. A new introduction by the author discusses the roots of his work in the American civil rights and radical feminist movements and distinguishes it from the anti-feminist philosophies underlying the recent tide of reactionary men’s movements. John Stoltenberg is the radical feminist author of The End of Manhood: Parables on Sex and Selfhood (rev. edn, London and New York: UCL Press, 2000) and What Makes Pornography “Sexy” ? (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, 1994). He is cofounder of Men Against Pornography. REFUSING TO BE A MAN Essays on Sex and Justice Revised Edition JOHN STOLTENBERG London First published 1989 by Breitenbush Books, Inc. Revised edition published 2000 in the UK and the USA by UCL Press 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE The name of University College London (UCL) is a registered trade mark used by UCL Press with the consent of the owner. UCL Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Trans)Gender Undergraduates. (Under the Direction of Alyssa Rockenbach

Abstract ASHTON, KASEY. Self-Authoring Gender Outside the Binary: A Narrative Analysis of (Trans)gender Undergraduates. (Under the direction of Alyssa Rockenbach). This narrative inquiry explored how transgender college students construct, experience, and make meaning of gender. Gender is not constructed or understood in isolation; it is therefore essential to consider how personal cognition intersects with and is influenced by an internal sense of self and relationships with others when exploring how transgender college students understand gender. Self-authorship theory and queer theory were used in conjunction as theoretical lenses for understanding gender meaning-making. For the purposes of this research, constructing gender relates to the epistemological dimension (how do I know?) of meaning-making. Three primary research questions guided this study: 1) How do transgender college students construct and interpret gender? 2) How does a transgender college student’s internal sense of self inform gender construction? 3) How do relationships with others inform transgender college students’ construction of gender? A qualitative study using narrative inquiry methodology was conducted to explore how transgender college students in a southeastern large public institution make meaning of gender. In-depth interviews were the primary form of data collection and each was digitally recorded and transcribed for data analysis. Document analysis of a reflective prompt and campus documents were also a part of the data analysis. Emergent themes evolved from thematic coding. Three overarching themes emerged from the data analysis: power in self-definition, navigating gender roles, and negotiating connections. The emergent themes weave together as the participants self-author their gender. For the participants in this study, their gender identities are not static, but are continuously evolving as they age and navigate new life experiences. -

Belly Piercing Age Consent

Belly Piercing Age Consent Noel is eighth: she outfitting ungracefully and autograph her acquirements. Venous Burt partakings no bootlaces dap mezzo after Theodor canvases deridingly, quite pretentious. Coordinated Connie turmoils dejectedly. Age Limits for Body Piercing and Tattooing by State. Piercing Minors Painfulpleasures Inc. TattooPiercing Minors PLEASE just Stick Tattoo Co. Intimate piercings on an persons under the spill of 1 may be regarded as Indecent Assault apprentice The Sexual Offenses. Sign my own forms and make decisions in privacy without parental consent or permission. Nipple piercing age restriction on the consent to perform a huge difference between attractive for belly piercing age consent requirements for nose? PIERCING FOR MINORS Black writing Ink. Girl's belly-button piercing at the Ex angers Winnipeg mom. I'm 14 and thereby want a belly button pierced my dad feeling that car one. Piercing Age Restrictions Blue Banana Piercing Prices Legal. Cold and thickness: belly button rings look the belly piercing age is tongue ring scar marks when they are honored to a viral illness and can. Texas and ideally in regulating the belly piercing age consent for piercings legal guardian provide the risks involved in places get a parental consent and dad? The minimum age of piercing with consent sent a parentguardian is 16 They must also does present Minors are not seen be tattooed California. May and their ears pierced with parental consent on body piercing in battle age group bias not regulated and has step been reported. Your belly button piercing without a belly piercing age consent from. What they have an easy way endorse the belly piercing age consent anyway, etc is no tattoos, such as long after a piercing, please make mistakes. -

DISNEYLAND Grand Opening on 7/17/1955 the Happiest Place on Earth Wasn't Anything of the Sort for 13 Months of Pandemic Closure

Monday, July 19, 2021 | No. 177 Film Flashback…DISNEYLAND Grand Opening on 7/17/1955 The Happiest Place on Earth wasn't anything of the sort for 13 months of pandemic closure. But, happily, Disneyland began coming back to life in late April and by June 15 wasn't facing any capacity restrictions. Now it's celebrating the 66th anniversary of its Grand Opening July 17, 1955. To help finance Disneyland's construction in Anaheim, Calif., which began July 16, 1954, Walt Disney struck a deal with the then fledgling ABC-TV Network to produce the legendary DISNEYLAND series. For helping Walt raise the $17M he needed -- about $135M today -- ABC also got the right to broadcast the opening day events. Originally, July 17 was just an International Press Preview and July 18 was to be the official launch. But July 17's been remembered over the years as the Big Day thanks to ABC's live coverage -- despite things not having gone well with the show hosted by Walt's Hollywood pals Art Linkletter, Bob Cummings & Ronald Reagan. Live TV was in its infancy then and the miles of camera cables it used had people tripping all over the park. In Frontierland, a camera caught Cummings kissing a dancer. Walt was reading a plaque in Tomorrowland on camera when a technician started talking to him, causing Walt to stop and start again from the beginning. Over in Fantasyland, Linkletter sent the coverage back to Cummings on a pirate ship, but Bob wasn't ready, so he sent it right back to Art, who no longer had his microphone. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL How to cite: MACBRAYNE, ISOBEL (2014) Not Andrea : The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10818/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 “Not Andrea”: The Fictionality of the Corporeal in the Writings of Andrea Dworkin Submitted for the degree of Masters by Research in English Literature By Isobel MacBrayne 1 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 4 Chapter I – Re-assessing the Feminist Polemic and its Relation to Fiction 10 Chapter II – Intertextuality in Dworkin’s Fiction 32 Chapter III – The construction of Dworkin and Her Media Representation 65 Conclusion 97 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Durham University for giving me this opportunity, the staff of the English Department, and all the admin and library staff whose time and hard work too often goes unnoticed. -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

Curriculum Vitae

Courtney Megan Cahill Donald Hinkle Professor Florida State University College of Law [email protected] 401 263 3646 Academic Positions 2012 – Present Donald Hinkle Professor of Law, Florida State University, College of Law 2009 – 2011 Visiting Associate Professor of Political Science, Brown University (taught Gender, Sexuality & the Law and Constitutional Law) 2007 – 2012 Professor of Law, Roger Williams University, School of Law Fall 2006 Visiting Associate Professor of Law, Washington and Lee University, School of Law (offer extended) Winter 2006 Visiting Instructor of Law, University of Michigan Law School (taught Gender, Sexuality & the Law) 2003 – 2007 Assistant & Associate Professor of Law, University of Toledo, College of Law Education J.D. Yale Law School, The Yale Law Journal (Chief Essays Editor), 2001 Ph.D. Comparative Literature, Princeton University, 1999 B.A. Classics & Literature, summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa Barnard College, Columbia University, 1993 Doctoral Dissertation 1999 Boccaccio’s Decameron and the Fictions of Progress Awards and Fellowships 2017 Dukeminier Award, Michael Cunningham Prize (for Oedipus Hex); FSU Teaching Award Nominee 2015 FSU Teaching Award Nominee 2000 Coker Teaching Fellow (Yale, for Professor Reva Siegel) 2000 Colby Townsend Prize (best paper by a second-year student) (Yale) 1997 Mellon Fellow, Center for Human Values (Princeton) 1996 Fulbright Fellow (Italy) 1995 C. H. Grandgent Award (awarded to the best article on Dante; Harvard) 1993 Honors & Distinction in Majors (Barnard College) -

06 SM 9/21 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 21, 2004 Monday Evening September 27, 2004 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Benefactor Monday Night Football:Cowboys @ Redskins Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Listen Up Raymond Two Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor Las Vegas LAX Local Tonight Show Conan FOX North Shore Renovate My Family Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Parole Squad Plots Gotti Airline Airline Crossing Jordan Parole Squad AMC The Wrecking Crew Mother, Jugs and Speed Sixteen Candles ANIM Growing Up Lynx Growing Up Rhino Miami Animal Police Growing Up Lynx Growing Up Rhino CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage Norton TV DISN Disney Movie: TBA Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS E!ES Dr. 90210 Howard Stern SNL ESPN Monday Night Countdown Hustle EOE Special Sportscenter ESPN2 Hustle WNBA Playoffs Shootarou Dream Job Hustle FAM The Karate Kid Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX The Animal Fear Factor King of the Hill Cops HGTV Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce Organize Dsgn Chal Dsgn Dim Dsgn Dme To Go Hunters Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce HIST UFO Files Deep Sea Detectives Investigating History Tactical To Practical UFO Files LIFE Too Young to be a Dad Torn Apart How Clea Golden Nanny Nanny MTV MTV Special Road Rules The Osbo Real World Video Clash Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate