History Salcombe Yacht Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

Meet the Competitors: Annapolis YC Double-Handed Distance Race

Meet the Competitors: Annapolis YC Double-handed Distance Race R.J. Cooper & Courtney Cooper Cumberland are a brother and sister team from Oxford, Maryland and Panama City, Florida. They have sailed together throughout their youth as well as while on the Sailing Team for the University of Florida. The pair has teamed up for a bid to represent the United States and win gold at the 2024 Olympics in Paris. They will be sailing Tenacious owned by AYC member Carl Gitchell. Sail #501 Erik Haaland and Andrew Waters will be sailing the new Italia Yachts 9.98 sport boat named Vichingio (Viking). Erik Haaland is the Sales Director for Italia Yachts USA at David Walters Yachts. He has sailed his entire life and currently races on performance sport boats including the Farr 30, Melges 32 and J70. Andrew Waters is a Sail and Service Consultant at Quantum Sails in Annapolis. His professional sailing career began in South Africa and later the Caribbean and includes numerous wins in large regattas. Sail #17261 Ethan Johnson and Cat Chimney have sailing experience in dinghies, foiling skiffs, offshore racers and mini-Maxis. Ethan, a Southern Maryland native now living in NY is excited to be racing in home waters. Cat was born on Long Island, NY but spent time in Auckland, New Zealand. She has sailed with Olympians, America’s Cup sailors and Volvo Ocean Race sailors. Cat is Technical Specialist and Rigger at the prestigious Oakcliff Sailing where Ethan also works as the Training Program Director. Earlier this year Cat and Ethan teamed up to win the Oakcliff Double-handed Melges 24 Distance Race. -

Journal of the of Association Yachting Historians

Journal of the Association of Yachting Historians www.yachtinghistorians.org 2019-2020 The Jeremy Lines Access to research sources At our last AGM, one of our members asked Half-Model Collection how can our Association help members find sources of yachting history publications, archives and records? Such assistance should be a key service to our members and therefore we are instigating access through a special link on the AYH website. Many of us will have started research in yacht club records and club libraries, which are often haphazard and incomplete. We have now started the process of listing significant yachting research resources with their locations, distinctive features, and comments on how accessible they are, and we invite our members to tell us about their Half-model of Peggy Bawn, G.L. Watson’s 1894 “fast cruiser”. experiences of using these resources. Some of the Model built by David Spy of Tayinloan, Argyllshire sources described, of course, are historic and often not actively acquiring new material, but the Bartlett Over many years our friend and AYH Committee Library (Falmouth) and the Classic Boat Museum Member the late Jeremy Lines assiduously recorded (Cowes) are frequently adding to their specific yachting history collections. half-models of yachts and collected these in a database. Such models, often seen screwed to yacht clubhouse This list makes no claim to be comprehensive, and we have taken a decision not to include major walls, may be only quaint decoration to present-day national libraries, such as British, Scottish, Welsh, members of our Association, but these carefully crafted Trinity College (Dublin), Bodleian (Oxford), models are primary historical artefacts. -

IT's a WINNER! Refl Ecting All That's Great About British Dinghy Sailing

ALeXAnDRA PALACe, LOnDOn 3-4 March 2012 IT'S A WINNER! Refl ecting all that's great about British dinghy sailing 1647 DS Guide (52).indd 1 24/01/2012 11:45 Y&Y AD_20_01-12_PDF.pdf 23/1/12 10:50:21 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The latest evolution in Sailing Hikepant Technology. Silicon Liquid Seam: strongest, lightest & most flexible seams. D3O Technology: highest performance shock absorption, impact protection solutions. Untitled-12 1 23/01/2012 11:28 CONTENTS SHOW ATTRACTIONS 04 Talks, seminars, plus how to get to the show and where to eat – all you need to make the most out of your visit AN OLYMPICS AT HOME 10 Andy Rice speaks to Stephen ‘Sparky’ Parks about the plus and minus points for Britain's sailing team as they prepare for an Olympic Games on home waters SAIL FOR GOLD 17 How your club can get involved in celebrating the 2012 Olympics SHOW SHOPPING 19 A range of the kit and equipment on display photo: rya* photo: CLubS 23 Whether you are looking for your first club, are moving to another part of the country, or looking for a championship venue, there are plenty to choose WELCOME SHOW MAP enjoy what’s great about British dinghy sailing 26 Floor plans plus an A-Z of exhibitors at the 2012 RYA Volvo Dinghy Show SCHOOLS he RYA Volvo Dinghy Show The show features a host of exhibitors from 29 Places to learn, or improve returns for another year to the the latest hi-tech dinghies for the fast and your skills historical Alexandra Palace furious to the more traditional (and stable!) in London. -

Women Skippers of the FSSA

Volume 63 x Number 1 x 2019 SECRETS OF WOMEN SARASOTA BAY SKIPPERS OF THE FSSA WHAT’S IN A NAME? END OF SEASON SAVINGS ORDER THE SAILS THAT DOMINATED IN 2018 1ST 2ND* 3RD 4TH 5TH 1ST 2ND* 3RD 1ST 2ND 3RD North Americans Midwinters Sandy Douglas Regatta Congratulations Zeke Horowitz Congratulations Zeke Horowitz Congratulations Charlie & Cindy Clifton 1ST 1ST 1ST North Americans - Challengers Div NE Districts GNY Districts Congratulations Randy Pawlowski Congratulations John Eckart Congratulations Dan Voughtn CONTACT YOUR REP FOR DETAILS Zeke Horowitz Brian Hayes 941-232-3984 [email protected] 203-783-4238 [email protected] *partial North Sails inventory Photo: Diane Kampf northsails.com CONTENTS OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE FLYING SCOT® SAILING ASSOCIATION x x Flying Scot® Sailing Association Volume 63 Number 1 2019 One Windsor Cove,Suite 305, Columbia, S.C. 29223 Email: [email protected] 803-252-5646 • 1-800-445-8629 FAX (803) 765-0860 Courtney LC Waldrup, Executive Secretary President’s Message ......................................................4 PRESIDENT Bill Vogler* You’ve Come a Long Way, Scottie: Part 1 .........................5 9535 US Highway 51 North Cobden, IL 62920 618-977-5890 • [email protected] Women Skippers of the FSSA ..........................................6 FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT What’s in a Name? For Many Flying Scots, a Story ..........11 Bill Dunham* 700 Route 22 Trinity-Pawling Pawling, NY 12564 Discover the Magic of Pensacola ...................................13 845-855-0619 • [email protected] -

Portsmouth Number List 2016

Portsmouth Number List 2016 The RYA Portsmouth Yardstick Scheme is provided to enable clubs to allow boats of different classes to race against each other fairly. The RYA actively encourages clubs to adjust handicaps where classes are either under or over performing compared to the number being used. The Portsmouth Yardstick list combines the Portsmouth numbers with class configuration and the total number of races returned to the RYA in the annual return. This additional data has been provided to help clubs achieve the stated aims of the Portsmouth Yardstick system and make adjustments to Portsmouth Numbers where necessary. Clubs using the PN list should be aware that the list is based on the typical performance of each boat across a variety of clubs and locations. Experimental numbers are based on fewer returns and are to be used as a guide for clubs to allocate as a starting number before reviewing and adjusting where necessary. The list of experimental Portsmouth Numbers will be periodically reviewed by the RYA and is based on data received from the PY Online website (www.pys.org.uk). Users of the PY scheme are reminded that all Portsmouth Numbers published by the RYA should be regarded as a guide only. The RYA list is not definitive and clubs should adjust where necessary. For further information please visit the RYA website: http://www.rya.org.uk/racing/Pages/portsmouthyardstick.aspx RYA PN LIST - Dinghy Change Class Name No. of Crew Rig Spinnaker Number Races Notes from '15 420 2 S C 1105 0 278 2000 2 S A 1101 1 1967 29ER 2 S A -

Twin Spinnaker Pole System W11012 String Launched with Twin Guys and Twin Sheets

Twin Spinnaker Pole System W11012 String launched with twin guys and twin sheets Twin spinnaker pole arrangements have been used in various classes for a number of years. An early arrangement was used in Hornets and Scorpions in the 1980’s and a push-out/manual twin pole system has been used by Merlin Rockets for about 20 years. A string launched pole is essentially one where the crew pulls on a control line to set the pole. The 505 class in particular was using string launched single ended poles through the 1980’s to the early part of this century and around the mid-noughties sailors in Australia and the USA started working on string launched twin pole setups for the 505 to go along with their long poles and mega- spinnakers. An interesting article was published on Sailing Anarchy a few years ago at http:// forums.sailinganarchy.com/index.php?/topic/101399-zen-and-the-art-of-making- the-5o5-double-pole-system/ which shows the development of the systems to twin poles and twin guys. The advantage for the 505 is that it enables a wire to wire gybe to be completed successfully in windy conditions without the crew having to stand by the mast wrestling with the pole. The advantage of using twin guys/sheets over using the traditional twinning lines is that it is possible to pre-set the lazy guy so that as it becomes the new guy following a gybe it is no longer necessary to set and release the twinning lines (which takes time). -

RAAF Super Hornet/JSF Missile Plans

ISSUE NO. 257 – THURSday 13TH JUNE 2013 SUBSCRIBER EDITION NEWS | INTELLIGENCE | BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES | EVENTS IN THIS ISSUE NATIONAL NEWS RAAF Super Hornet/JSF missile plans . 1 The Pacific Patrol Boat program . 2 Cyber centre boss confirmed . 3 Supercomputer for DSTO’s work with future sub . 4 DSTO to separate corporate and R&D . 5 TC Communications and ADF sign WGS contract . 5 Expanding manufacturer sets up blasting room . 6 Mediaware and Sentient team-up . 7 FireEye release Australian cyber security survey findings . 7 J&H Williams awarded the DTC Defence RAAF Super Hornet/JSF missile Industry Member Award . 8 US IOC for JSF . 8 plans Movement at the station . 9 Tom Muir ADM Online: Weekly Summary . 9 INTERNATIONAL NEWS Back in April it was announced that Raytheon Missile US to replace M113s - we Systems had received a $US12.7 million order to integrate upgrade ‘em . 10 the new AGM-154C-1 JSOW into the F/A-18E/F aircraft’s H10E Canada’s LAV-III surveillance needs . 10 Operational Flight Program (core operating system) software. ITT Exelis to provide US Navy aircraft This JSOW variant can hit moving naval targets, turning the stealthy with advanced electronic glide bomb into a short range anti-ship missile. Work is expected to countermeasures . 11 be completed by February 2015. FORTHCOMING EVENTS .......12 With Norway’s decision to procure the F-35, the Royal Norwegian DEFENCE BUSINESS Air Force needs a modern weapon system for its new aircraft, and has OPPORTUNITIES...See separate PDF decided to develop a new missile, the Joint Strike Missile (JSM), PUBLISHING CONTACTS: which can be carried externally and internally in the bomb bay of the EDITOR F-35. -

Hierarchical Bayesian Model (HBM)- Derived Estimates of Air Quality for 2008: Annual Report Developed by the U.S

Disclaimer The information in this document has been funded wholly by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under a ‘funds-in’ interagency agreement RW75922615-01-3 with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It has been subjected to the Agency’s peer and administrative review and has been approved for publication as an EPA document. EPA/600/R-12/048 | July 31,2012 | www.epa.gov/ord Hierarchical Bayesian Model (HBM)- Derived Estimates of Air Quality for 2008: Annual Report Developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development (ORD) National Exposure Research Laboratory (NERL) And Office of Air and Radiation (OAR) Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards (OAQPS) Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory Contributors: Eric S. Hall (EPA/ORD) Alison M. Eyth (EPA/OAR) Sharon B. Phillips (EPA/OAR) Richard Mason (EPA/OAR) Project Officer Eric S. Hall National Exposure Research Laboratory (NERL) 109 T.W. Alexander Dr. Durham, NC 27711-0001 Acknowledgements The following people served as reviewers of this document and provided valuable comments that were included: Alexis Zubrow (EPA/OAR), Richard Mason (EPA/OAR), Norm Possiel (EPA/OAR), Kirk Baker (EPA/OAR), Carey Jang (EPA/OAR), Tyler Fox (EPA/OAR), Rachelle Duvall (EPA/ORD), Melinda Beaver (EPA/ORD), and OAR/OAQPS support contractors from Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC). Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction. 1 2.0 Air Quality Data . 3 2.1 Introduction to Air Quality Impacts in the United States -

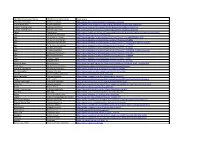

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read More

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read more a European Hoverfly Pocota personata https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/pocota-personata a small black wasp Stigmus pendulus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/crabronidae/pemphredoninae/stigmus-pendulus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius concinnus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-concinnus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius nigerrimus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-nigerrimus Adder Vipera berus https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/animals/reptiles-and-amphibians/adder/ Alga Cladophora glomerata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladophora Alga Closterium acerosum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=x44d373af81fe4f72 Alga Closterium ehrenbergii https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28183 Alga Closterium moniliferum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28227&sk=0&from=results Alga Coelastrum microporum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27402 Alga Cosmarium botrytis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28326 Alga Lemanea fluviatilis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=32651&sk=0&from=results Alga Pediastrum boryanum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27507 Alga Stigeoclonium tenue https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=60904 Alga Ulothrix zonata https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=562 Algae Synedra tenera https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=34482 -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Centreboards – How They Work

Gybing boards – how they work… By Strangler -I do not claim to …And a look at a few other things along the way. be an expert. There may well be ‘Foil’ is the common term for centerboards, rudders, keels and wings mistakes in the detail but (the type on airplanes, not 49ers!). To the aerodynamicist and hopefully the general principals hydrodynamicist they are all the same. This term is used here where are near enough correct. Comments on a postcard. relevant to centreboards and rudders. THE BASICS and non-gybing boards. A centreboard [CB] that is passing straight through the water does nothing for a sailboat [Fig 1] except cause drag (and decrease roll - if the hull rolls from side to side water has to slosh from one side of the board round to the other [Fig 2], this slows any rolling motion). CBs work by meeting the oncoming water at an angle (leeway angle) like an airplane wing, thus creating lift. So what does a CB do? If those nasty race officers did not make us slog our way upwind CBs would be of far less importance. But as it is, they are one ingredient in the witches brew that is the Black Art of sailing upwind fast. The underwater shape of a CB is designed solely with beating in mind – thats when the CB is needed most, when the side forces from the rig are greatest. The effect it has is like putting the boat on rails, making it go forwards rather than sliding sideways. Imagine a sailboat beating to windward, the sails are sheeted right in with the boom almost on the centreline.