Scottish Studies 38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2003 Archipelago

archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 7, No. 3 Fall 2003 AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC An Exhibiton : Twenty-two Irish and Scottish Gaelic Poems, Translations and Artworks, with Essays and Recitations Fiction: PATRICIA SARRAFIAN WARD “Alaine played soccer with the refugees, she traded bullets and shrapnel around the neighborhood . .” from THE BULLET COLLECTION Poem: ELEANOR ROSS TAYLOR Our Lives Are Rounded With A Sleep Reflection: ANANT KUMAR The Mosques on the Banks of the Ganges: Apart or Together? tr. from the German by Rajendra Prasad Jain Photojournalism: PETER TURNLEY Seeing Another War in Iraq in 2003 and The Unseen Gulf War : Photographs Audio report on-line by Peter Turnley Endnotes: KATHERINE McNAMARA The Only God Is the God of War : On BLOOD MERIDIAN, an American myth printed from our pdf edition archipelago www.archipelago.org CONTENTS AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC 4 Introduction : Malcolm Maclean 5 On Contemporary Irish Poetry : Theo Dorgan 9 Is Scith Mo Chrob Ón Scríbainn ‘My hand is weary with writing’ 13 Claochló / Transfigured 15 Bean Dubh a’ Caoidh a Fir Chaidh a Mharbhadh / A Black Woman Mourns Her Husband Killed by the Police 17 M’anam do sgar riomsa a-raoir / On the Death of His Wife 21 Bean Torrach, fa Tuar Broide / A Child Born in Prison 25 An Tuagh / The Axe 30 Dan do Scátach / A Poem to Scátach 34 Èistibh a Luchd An Tighe-Se / Listen People Of This House 38 Maireann an t-Seanmhuintir / The Old Live On 40 Na thàinig anns a’ churach -

SCQF Level 6 Bagpipes Practical

Z The Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association Pipe Band College Certification Education Guidelines PDQB CERTIFICATE - SCQF 6 Bagpipes This guide is intended for both Students and Instructors. It must be read in conjunction with SCQF 6 Bagpipes Syllabus to ensure all aspects are covered. Refer www.pdqb.org. It is strongly recommended that all students sitting this level have access to the RSPBA Structured Learning Books. It is also recommended to purchase The College of Piping Tutor 4 – Piobaireachd be purchased. It is therefore important that Instructors use these recommended books as their main source material. The RSPBA Structured Learning Books are available free from the RSPBA Pipe Band College :- https://www.rspba.org/ Obtain College of Piping Tutor 4 Knowledge of SCQF 2 through 5 are essential for SCQF 6. Students who start at SCQF 6 may be required to prove competency of prior levels by the Examiner. Be prepared for this. Theory Aspects: • Write bars of a monotone rhythm in various combinations e.g. Compound Duple time / Cut Common time / Common time etc. And be able to consider rests in the combinations and ensure each bar has different combination of note values. • Explain the accent pattern in reels and describe two important factors in reel playing – could be any type of tune – say Reel or Strathspey etc– accent pattern - Simple Duple Time meaning 2 beats in the Bar SW for reel or Simple Quadruple Time SWMW for Strathspey etc. – important factors in playing different types of tunes – discuss this e.g. good technique, appropriate tempo, decision of round or dot cut etc. -

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the Deer, Is in the Wood: Chronotopic Identities, Trajectories of Texts and Community Self-Management

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the deer, is in the wood: chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management. Applied Linguistics Review, (doi: 10.1515/applirev-2019-0134). This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/201608/ Deposited on: 24 October 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Tom Bartlett Time, the deer, is in the wood: Chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management Abstract: This paper opens with a problematisation of the notion of real-time in discourse analysis – dissected, as it is, as if time unfolded in a linear and regular procession at the speed of speech. To illustrate this point, the author combines Hasan’s concept of “relevant context” with Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope to provide an analysis of Sorley MacLean’s poem Hallaig, with its deep-rootedness in space and its dissolution of time. The remainder of the paper is dedicated to following the poem’s metamorphoses and trajectory as it intertwines with Bartlett’s own life and family history, creating a layered simultaneity of meanings orienting to multiple semio-historic centres. In this way the author (pers. comm.) “sets out to illustrate in theory, text analysis and (self-)history the trajectories taken by texts as they cross through time and space; their interconnectedness -

NOTING the TRADITION an Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre

NOTING THE TRADITION An Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre Interviewee Professor Roddy Cannon Interviewer James Beaton Date of Interview 30 th November 2012 This interview is copyright of the National Piping Centre Please refer to the Noting the Tradition Project Manager at the National Piping Centre, prior to any broadcast of or publication from this document. Project Manager Noting The Tradition The National Piping Centre 30-34 McPhater Street Glasgow G4 0HW [email protected] Copyright, The National Piping Centre 2012 This is James Beaton for ‘Noting the Tradition.’ I’m here in the National Piping Centre with Professor Roddy Cannon, piper, piping historian and researcher, and also professionally a scientist. It’s St Andrew’s Day 2012 and we’re going to be speaking really about Roddy’s life and times in piping. Roddy, good morning and welcome. Good morning. Good morning. It’s always good to be back. Well, it’s nice to see you here and it’s nice to have you back. I come here on averageabout once a year these days. I give a number of classes and I talk to your students and I talk to the staff and I talk to you and it’s wonderful. Well, it’s nice to have you here. The thing that strikes me very much about your classes is that they’re so different from one year to the next. Some sit quietly and listen, some of them join the debate vigorously, and very occasionally I get confuted by counter arguments and that’s what I like best. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents

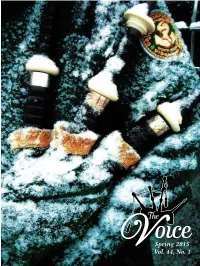

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents 4 President’s Message Music 5 Editorial 33 Jimmy Tweedie’s Sealegs 6 Letters to the Editor 43 Report for the Reviews Executive Secretary 34 Review of Gibson Pipe Chanter Spring 2015 35 The Campbell Vol. 44, No. 1 Basics Tunable Chanter 9 Snare Basics: Snare FAQ THE VOICE is the official publication of the Eastern United 11 Bass & Tenor Basics: Semiquavers States Pipe Band Association. Writing a Basic Tenor Score 35 The Making of the 13 Piping Basics: “Piob-ogetics” Casco Bay Contest John Bottomley 37 Pittsburgh Piping EDITOR [email protected] Features Society Reborn 15 Interview Shawn Hall 17 Bands, Games Come Together Branch Notes ART DIRECTOR 19 Willie Wows ‘Em 39 Southwest Branch [email protected] 21 The Last Happy Days – 39 Metro Branch Editorial Inquiries/Letters the Great Highland Bagpipe 40 Ohio Valley Branch THE VOICE in JFK’s Camelot 41 Northeast Branch [email protected] ADVERTISING INQUIRIES John Bottomley [email protected] THE VOICE welcomes submissions, news items, and ON THE COVER: photographs. Please send your Derek Midgley captured the joy submissions to the email above. of early St. Patrick’s parades in the northeast with this photo of Rich Visit the EUSPBA online at www.euspba.org Harvey’s pipe at the Belmar NJ event. ©2014 Eastern United States Pipe Band EUSPBA MEMBERS receive a subscription to THE VOICE paid for, in part, Association. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted by their dues ($8 per member is designated for THE VOICE). -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

The Isle of Lewis & Harris (Chaps. VII & VIII)

THE ISLE OF LEWIS AND HARRIS CHAPTER I A STUDY IN ENVIRONMENT AND LANDSCAPE BRITISH COMMUNITY (A) THE GEOGRAPHIC SETTING: THE BRITISH ISLES, SCOTLAND AND THE by HIGHLANDS AND ISLES ARTHUR GEDDES i. A 'Heart' of the 'North and West' of Britain The Isle of Lewis and Harris (1955) by Arthur Geddes, the son N the ' Outer' Hebrides, commonly regarded as the of the great planner and pioneering human ecologist Patrick Geddes, is long out of print from EUP and hard to procure. most ' outlying ' inhabited lands of the British Isles, Chapters VII and VIII on the spiritual and religious life of the I are revealed not only the most ancient of British rocks, community remain of very great importance, and this PDF of the Archaean, but probably the oldest form of communal them has been produced for my students' use and not for any life in Britain. This life, in present and past, will interest commercial purpose. Also, below is Geddes' remarkable map of the Hebrides from p. 3, and at the back the contents pages. Alastair Mclntosh, Honorary Fellow, University of Edinburgh. EDINBURGH AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS *955 FIG. I.—Global view of the ' Outer' Hebrides, seen as the heart of the ' North and West' of Britain. 3 CH. VII SPIRITUAL LIFE OF COMMUNITY xviii. 19-20). The worldly wise might think that the spiritual fare of these poor folk must have been lean indeed ; while others, having heard much of the Highlanders' ' pagan ' superstitions, may think even worse ! The evi CHAPTER VII dence from which to judge is found in survivals from a rich lore, and for most readers seen but ' darkly' through THE SPIRITUAL LIFE OF THE prose translations from the poetry of a tongue now known COMMUNITY to few. -

Health and Social Care NITHSDALE LOCALITY REPORT March 2021

Dumfries and Galloway Integration Joint Board Health and Social Care NITHSDALE LOCALITY REPORT March 2021 Version: DRAFT March 2021 1. General Manager’s Introduction 1.1 The COVID-19 Pandemic The past year has presented unprecedented challenges for health and social care across Dumfries and Galloway. The first 2 cases of COVID-19 in the UK were confirmed by 31 January 2020. The first positive cases in Dumfries and Galloway were identified on 16 March 2020. Following direction from the Scottish Government, in March 2020 Dumfries and Galloway Health and Social Care Partnership started their emergency response to the pandemic. Hospital wards were emptied and some cottage hospitals temporarily closed. Many planned services were stopped whilst others changed their delivery model. Many staff were redeployed to assist with anticipated high levels of demand across the Partnership. There were many issues that had to be addressed including: the supply and distribution of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) across the Health and Social Care system over 500 people’s regular care and support ‘packages’ were readjusted to respond to the needs presented by COVID-19 our relationships with care homes changed significantly we quickly kitted out a site that could be used as a temporary cottage hospital in Dumfries During the period of June to October 2020, the Partnership focused on adapting services to reflect the heightened infection prevention and control measures needed to combat COVID-19 and rapidly expanding COVID-19 testing capacity across the region. We rolled out training and technology to enable many more video and telephone consultations. We had to rethink how people could access our premises, with additional cleaning and social distancing to keep people safe.