Art Criticism /, '\

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory of the William A. Rosenthall Judaica Collection, 1493-2002

Inventory of the William A. Rosenthall Judaica collection, 1493-2002 Addlestone Library, Special Collections College of Charleston 66 George Street Charleston, SC 29424 USA http://archives.library.cofc.edu Phone: (843) 953-8016 | Fax: (843) 953-6319 Table of Contents Descriptive Summary................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical and Historical Note...............................................................................................3 Collection Overview...................................................................................................................4 Restrictions................................................................................................................................ 5 Search Terms............................................................................................................................6 Related Material........................................................................................................................ 5 Separated Material.................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information......................................................................................................... 7 Detailed Description of the Collection.......................................................................................8 Postcards.......................................................................................................................... -

Press Release for Immediate Release Berry Campbell Presents Raymond Hendler: Raymond by Raymond (Paintings 1957-1967)

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BERRY CAMPBELL PRESENTS RAYMOND HENDLER: RAYMOND BY RAYMOND (PAINTINGS 1957-1967) NEW YORK, NEW YORK, June 29, 2021—Berry Campbell is pleased to announce its fourth exhibition of paintings by Raymond Hendler (1923-1998). Raymond Hendler: Raymond by Raymond (Paintings 1957-1967) features paintings created between 1957 and 1967, a transitional period for Hendler in which the artist moved away from an Abstract Expressionist mode and employed a more stylized line, producing distinct shapes and symbols. The exhibition is accompanied by a 16-page catalogue with an essay written by Phyllis Braff. Raymond Hendler: Raymond by Raymond (Paintings 1957-1967) opens July 8, 2021 and continues through August 20, 2021. Gallery summer hours are Monday - Friday, 10 am - 6 pm. ABOUT THE ARTIST A first-generation action painter, Raymond Hendler started his career as an Abstract Expressionist in Paris as early as 1949. In the years that followed, he played a significant role in the movement, both in New York, where he was the youngest voting member of the New York Artist’s Club. Hendler became a friend of Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Harold Rosenberg in Philadelphia, where he ran an avant-garde gallery between 1952 and 1954. Raymond Hendler was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1923 and studied in his native Philadelphia, at the Graphic Sketch Club, the Philadelphia College of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Art, and the Tyler School of Art (Temple University). In 1949, he continued his art training in Paris at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière on the G.I. -

The US Footwear Industry Market Drivers

An In-depth Look at Footwear Retail YTD The U.S. Footwear Industry Market Drivers 12 months ending Jun ‘15 Prepared for FDRA members September 2015 Copyright 2015. The NPD Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. This presentation is Proprietary and Confidential and may not be disclosed in any manner, in whole or in part, to any third party without the express written consent of NPD. The NPD Group, Inc. | Proprietary and Confidential Introduction The NPD Group provides market information and advisory services to help our clients make better business decisions. We help companies develop and offer the right products and get them in the right places at the right prices for the right people in order to grow their businesses. For more information, visit npd.com and npdgroupblog.com. Follow us on Twitter: @npdgroup. The NPD Group, Inc. | Proprietary and Confidential 2 Highlights The total footwear market is estimated at $64B for the 12 months ending (ME) Jun’15 and grew +5% YOY. Footwear has benefited from consumers’ increased spending on health and wellness categories, driving the comfort and athletic markets. ■ Women’s footwear represents the largest wearer segment, and generated an absolute dollar gain around +$1.3B. Men’s footwear also contributed over +$1B in incremental sales. ■ Millennials drove industry dollar growth, particularly ages 25-34. This segment increased +37%. But still keep watch on 65+ consumers which increased +14%, generating over +$500MM in growth volume. ■ Online footwear sales totaled $15 billion, up +13% in dollar sales. 23% of total footwear dollar sales are generated online. ■ Performance footwear contributed the largest dollar volume growth of about +$2B. -

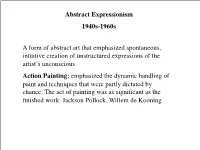

Art in 1960S

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1960s A form of abstract art that emphasized spontaneous, intuitive creation of unstructured expressions of the artist’s unconscious Action Painting: emphasized the dynamic handling of paint and techniques that were partly dictated by chance. The act of painting was as significant as the finished work: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1975 Color-Field Painting: used large, soft-edged fields of flat color: Mark Rothko, Ab Reinhardt Mark Rothko, Lot 24, “No. 15,” 1952 “A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high…a pure, abstract, non- objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting -- an object that is self conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti-art). Ad Reinhardt, Abstract Painting,1963 –Ad Reinhardt Minimalism 1960s rejected emotion of action painters sought escape from subjective experience downplayed spiritual or psychological aspects of art focused on materiality of art object used reductive forms and hard edges to limit interpretation tried to create neutral art-as-art Frank Stella rejected any meaning apart from the surface of the painting, what he called the “reality effect.” Frank Stella, Sunset Beach, Sketch, 1967 Frank Stella, Marrakech, 1964 “What you see is what you see” -- Frank Stella Postminimalism Some artists who extended or reacted against minimalism: used “poor” materials such felt or latex emphasized process and concept rather than product relied on chance created art that seemed formless used gravity to shape art created works that invaded surroundings Robert Morris, Felt, 1967 Richard Serra, Cutting Device: Base Plat Measure, 1969 Hang Up (1966) “It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. -

The Modernist Iconography of Sleep. Leo Steinberg, Picasso and the Representation of States of Consciousness

60 (1/2021), pp. 53–73 The Polish Journal DOI: 10.19205/60.21.3 of Aesthetics Marcello Sessa* The Modernist Iconography of Sleep. Leo Steinberg, Picasso and The Representation of States of Consciousness Abstract In the present study, I will consider Leo Steinberg’s interpretation of Picasso’s work in its theoretical framework, and I will focus on a particular topic: Steinberg’s account of “Picas- so’s Sleepwatchers.” I will suggest that the Steinbergian argument on Picasso’s depictorial modalities of sleep and the state of being awake advances the hypothesis of a new way of representing affectivity in images, by subsuming emotions into a “peinture conceptuelle.” This operation corresponds to a shift from modernism to further characterizing the post- modernist image as a “flatbed picture plane.” For such a passage, I will also provide an overall view of Cubism’s main phenomenological lectures. Keywords Leo Steinberg, Pablo Picasso, Cubism, Phenomenology, Modernism 1. Leo Steinberg and Picasso: The Iconography of Sleep The American art historian and critic Leo Steinberg devoted relevant stages of his career to the interpretation of Picasso’s work. Steinberg wrote several Picassian essays, that appear not so much as disjecta membra but as an ac- tual corpus. In the present study, I will consider them in their theoretical framework, and I will focus on a particular topic: Steinberg’s account of “Pi- casso’s Sleepwatchers” (Steinberg 2007a). I will suggest that the Steinber- gian argument on Picasso’s depictorial modalities of sleep and the -

Ex Libris Stamp of Gershom Scholem, ( 1897-1982 )

1. Gershom Scholem – Ex Libris stamp Gershom Scholem – Ex Libris Stamp Ex Libris stamp of Gershom Scholem, ( 1897-1982 ) Metal-cut on a wooden base, inscribed in Hebrew: ”Misifrei Gershom Scholem, Be’tochechei Yerushalayim” - from the library of Gershom Scholem, Jerusalem”. 2x2.5 inches. See illustration on front cover £1,500 Gershom Gerhard Scholem was one of the major influences on Jewish intellectual life in the 20th Century. Arriving in Palestine in 1923 he became the librarian at the Hebrew University where he began to teach in 1925. Scholem revolutionised the study of Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalah and made it the subject of serious academic study. He also played a very significant role in Israeli intellectual life. This is a one off opportunity to acquire his ex libris stamp. Judaica 2. Bialik, Haim Nachman. Halachah and Aggadah. London, 1944. Wraps. 28 pp. A translation of Bialik’s famous essay comparing the nature of Halachah and Aggadah. £10 3. Braham, Randolph L (ed). Hungarian Jewish Studies. New York, World Federation of Hungarian Jews, 1966. Cloth in slightly worn dj., 346 pp. Essays by: Ernest (Erno) Martin, The Family Tree of Hungarian Jewry; Erno Laszlo, Hungarian Jewry Settlement and Demography 1735-8 to 1910; Nathaniel Katzburg, Hungarian Jewry in Modern Times Political and Social Aspects; Bela Vago, The Destruction of the Jews of Transylvania; Randolph Braham, The Destruction of the Jews of Carpatho Ruthenia; Ilona Benoschofsky, The Position of Hungarian Jewry after the Liberation; Eugene Levai, Research Facilities in Hungary Concerning the Catastrophe Period; Moshe Carmilly-Weinberger, Hebrew Poetry in Hungary. £52 4. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

Intermediate Painting: Impression, Surrealism, & Abstract

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Course Outlines Curriculum Archive 5-2017 Intermediate Painting: Impression, Surrealism, & Abstract Jessica Agustin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/art-course-outlines Recommended Citation Agustin, Jessica, "Intermediate Painting: Impression, Surrealism, & Abstract" (2017). Course Outlines. 7. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/art-course-outlines/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Curriculum Archive at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Course Outlines by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLASS TITLE: Intermediate Painting DATE: 01/19/2017 SITE: CIM- C Yard TEACHING ARTIST: Jessica Revision to Current Class OVERVIEW OF CLASS In this course, participants will investigate different forms of painting through discussion and art historical examples. Participants will practice previously learned technical skills to explore more conceptual themes in their paintings. At the same time, participants will also learn to experiment with various formal/technical aspects of painting. Intermediate Painting will constitute of a lot of brainstorming, sketching (if needed) and Studio Time and reflection/discussion. ESSENTIAL QUESTION OR THEME What are some of art movements that have influenced art making/painting and how can we apply them to our work? STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES These should include at least 3 of the 4 areas: • Technical/ skill o Participants will use their technical skills to build their conceptual skills. • Creativity/ imagination o Participants will learn to take inspiration from their surroundings. o Participants will learn about different types of art styles/movement that will get them out of their comfort zone and try new techniques. -

San Antonio River Walk Designated to Receive an AJA Award; Rice Design Alliance Sponsors High-Powered Panel on Architecture Criticism

• A winning combination. When classic styling and continuous durability are ... ~~ • brought to- gether the re sult is excellence. This quality of excellence is obvious in all the materials at D'Hanis Clay Products. The care taken at every stage of the manufacturing process be comes evident in the end product. All of which brings us to another winning com bination: construction and D'Hanis Clay Products. [)'lIJ\Nl6 ClJL\Y PQODUCT~ GONTINLJOUS PRODUCTION SINCE 1905 11( >X 1fi', O'I !ANIS, Tf XAS 78850 AN ANH NI l t I ) I 4 0 ltANll1 (5n) 363-7221 CLEIS European Style Whirlpool Bathing Systems &ka½ 4 HESSCO FEATURING • 18 MODELS, 28 SIZES • COMPETITIVE PRICING • MATCH ANY COLOR • PROMPT DELIVERY • INDIVIDUAL JET CONTROLS • COMPLETELY PREPLUMBED CONTENTS IN THE NEWS 22 Dallas Museum ofArt opens to rave reviews; San Antonio River Walk designated to receive an AJA award; Rice Design Alliance sponsors high-powered panel on architecture criticism. ABOUT THIS ISSUE 41 42 SMALL BUILDINGS 42 Articles on eight recent Texas projects that represent a broad range ofproblems and solutions while falling into the same general category-small buildings. INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES MOORE 70 11 NEW TEXAS FELLOWS 84 Profiles of I I Texas architects elected to the American lnstitute's College of Fellows for outstanding contributions to architecture. BOOKS 76 48 INDEX TO ADVERTISERS 98 DA VE BRADEN/MUSINGS 98 COMING UP: Next issue, Texas Architect looks at architecture and transportation. ON THE COVER: William T. Cannady' s Fayeue Savings 58 Association in LaGrange. Photo by Paul Hester. 70 I , , llrchurrt .\furth·April 198-1 5 RENNER PIAl.A - o.11.b Nth,tnr ANPtl, ltK C,,,,,.,,•I Contr,1<fo, I h'1,y &•kl•nM & l"lll"'""'nR 0.wnM Contr,1<l<>r M.-1ro,t(J/,1.1n GI.tu, 'i<,11,J,.,lk•, r,,..., (,l,M /,y - rl'fflP(f/J<S fio,/cl,ipp/•,J no/It_,,,. -

Food Service Stuff

STATE OF THE CONSUMER The NPD Group, Inc. | Proprietary and confidential U.S. Consumer Economy Improving Economy Food and Retail Challenges Major economic indicators point to recovery, as consumers Cost increases for certain expenditures are shifting consumer are more confident, income is on the rise, and GDP posts gains budget priorities, and changing demographics create headwinds Consumer confidence has remained high Healthcare and other spending categories 129 for the past year are taking a greater share of our budget Restaurant prices have risen faster than Disposable personal income reached a new high household income Consumer spending growth is the leading contributor Our aging population is reshaping household to gains in GDP dynamics and influencing consumption patterns Consumers exhibiting an Soft but improving retail Result interesting shift in spending Can the food industry spending across a broad to the experiential—like find a way to tap into range of consumption- activities or entertainment oriented categories this trend? The NPD Group, Inc. | Proprietary and confidential 2 Canadian Consumer Economy Slow but Steady Economy Food and Retail Challenges Major economic indicators broadcast a mixed signal Cost increases for certain expenditures are shifting consumer budget priorities, and changing demographics create headwinds Groceries, utilities and the basics are the costs that Consumer confidence has remained high consumers are most worried about in their 116 for the past year, but is down this month household budgets Restaurant -

In 2006 USD, the World Toy Market Adds To: 2006 2007 (2006 Exchange Rates) World Toy Market $67.030 $70.398 Bn +5.0%

AUTOMOTIVE BEAUTY COMMERCIAL TECHNOLOGY CONSUMER TECHNOLOGY ENTERTAINMENT FASHION FOOD & BEVERAGE FOODSERVICE HOME OFFICE SUPPLIES SOFTWARE SPORTS TOYS WIRELESS June, 2008 Copyright 2008. The NPD Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. This presentation is Proprietary and Confidential and may not be disclosed in any manner, in whole or in part, to any third party without the express written consent of NPD. Content Objectives & Methodology Toy Markets in the World 2 Proprietary and Confidential Objective & Methodology 3 Proprietary and Confidential Objective Leverage The NPD knowledge and expertise in the Toy Industry to provide with an estimate of the Toy markets around the World. Because The NPD Group already operates on the Toy Industry in more than 12 countries, we have developed a market estimate statistical model based on this accurate information. It's a logical place to start, as some of these countries have been covered by The NPD Group for a long period. 4 Proprietary and Confidential The Concept The primary factors that drive the Toys & Games market consumption over the period are: – Average expenditures per child, – Changes in population age groups, – GDP per inhabitant and change in GDP per inhabitant. The business-as-usual projection of the Toys & Games market sizes were produced, using the projections of these driving variables provided by IMF, the UN, and The NPD Group. The framework assumptions involved in this business-as-usual projection are: – The richer the country is, the higher the Average Expenditure in Toys per Child (AETC), – The richer the country is, the larger proportion of Consumers 15 years old and over. 5 Proprietary and Confidential Methodology Statistical models from the 12 existing markets NPD already operates: – Toys Consumer Panel: Australia, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, UK, U.S.A. -

Haggadah: Why Is This Book Different? January 21, 2014 - March 18, 2014 Smathers Library Gallery, 2Nd Floor Curated by Rebecca Jefferson

Haggadah: why is this book different? January 21, 2014 - March 18, 2014 Smathers Library Gallery, 2nd Floor Curated by Rebecca Jefferson Haggadah: Why is This Book Different? tells the story of how a Jewish text compiled in antiquity was adapted and reproduced over time and around the world. Featuring rare and scarce Haggadot (plural) from the Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, this exhibition shows the many ways in which the core Haggadah text, with its Passover rituals, blessings, prayers and Exodus narrative, was supplemented by songs, commentary and rich illuminations to reflect and respond to each unique period and circumstance in which the Jewish diaspora found itself. Outstanding and unusual examples are included, such as a sumptuous facsimile of the Barcelona Haggadah from the 14th century, a 1918 Haggadah from Odessa, Ukraine, the last Haggadah produced before Soviet censorship, and a Haggadah recently produced by the Jewish community of Jacksonville in remembrance of the Holocaust. This exhibition charts the development of a fascinating text over 600 years and encourages you to compare the ways in which older copies of the Haggadah were illuminated in contrast with more recent artistic interpretations. It invites you to observe how the Exodus story with its essential message about freedom is interpreted in light of contemporary events and to notice the many ways in which the text is adapted to suit the audience and preserve its relevance. What is this book? During the first two nights of Passover, a ceremonial dinner and ritual service, known as a Seder, is conducted in Jewish homes around the world.