The Painted Word a Bantam Book / Published by Arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba

LIKE RABBITS Welcome to TimesPeople TimesPeople Lets You Share and Discover the Bes Get Started HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Books WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYL ART & DESIGN BOOKS Sunday Book Review Best Sellers First Chapters DANCE MOVIES MUSIC John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba By CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT Sig Published: January 28, 2009 wee SIGN IN TO den RECOMMEND John Updike, the kaleidoscopically gifted writer whose quartet of Cha Rabbit novels highlighted a body of fiction, verse, essays and criticism COMMENTS so vast, protean and lyrical as to place him in the first rank of E-MAIL Ads by Go American authors, died on Tuesday in Danvers, Mass. He was 76 and SEND TO PHONE Emmetsb Commerci lived in Beverly Farms, Mass. PRINT www.Emme REPRINTS U.S. Trus For A New SHARE Us Directly USTrust.Ba Lanco Hi 3BHK, 4BH Living! www.lancoh MOST POPUL E-MAILED 1 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. All rights reserved. 7/9/2009 10:55 PM LIKE RABBITS 1. Month Dignit 2. Well: 3. GLOB 4. IPhon 5. Maure 6. State o One B 7. Gail C 8. A Run Meani 9. Happy 10. Books W. Earl Snyder Natur John Updike in the early 1960s, in a photograph from his publisher for the release of “Pigeon Feathers.” More Go to Comp Photos » Multimedia John Updike Dies at 76 A star ALSO IN BU The dark Who is th ADVERTISEM John Updike: A Life in Letters Related An Appraisal: A Relentless Updike Mapped America’s Mysteries (January 28, 2009) 2 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. -

Author Tom Wolfe

University Events Office presents lecture by "The Right Stuff" author Tom Wolfe May 8, 1986 Tom Wolfe, the man who put La Jolla's Windansea on the map in 1968 when his "Pump House Gang" chronicled the life of the surfers who hung out around the beach's pump house, will speak on "The Novel in an Age of Nonfiction," at 8 p.m. Thursday, May 22, in the University of California, San Diego's Main Gymnasium. Wolfe's book, "The Right Stuff," published in 1979, is a pithy view of the first astronauts and the early days of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's space program. "The Right Stuff" became a runaway best seller and won the American Book Award for general nonfiction. After his first book, "The Kandy Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby," Wolfe wrote "The Electric Kool- Aid Acid Test," a tale about LSD and a group of people who drove around the country in a multicolored bus calling themselves the Merry Pranksters; and "The Pump House Gang," all of which became undergraduate student bibles. In 1970, Wolfe published "Radical Chic and Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers," a devastatingly funny portrayal of American political stances and social styles. In 1975, he published "The Painted Word," a humorous look at the world of modern art, which received a special citation from the National Sculpture Society. "Mauve Gloves and Madmen, Clutter and Vine," is a collection of essays which was published in 1976. In 1980, Wolfe published his first collection of drawings, entitled, "In Our Time." In 1981, he took a distinctive look at contemporary architecture in his book, "From Bauhaus to Our House." This work was followed by "The Purple Decades: A Reader." Wolfe grew up in Richmond, Virginia. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Plastic Dynamism in Pastel Modernism: Joseph Stella's

PLASTIC DYNAMISM IN PASTEL MODERNISM: JOSEPH STELLA’S FUTURIST COMPOSITION by MEREDITH LEIGH MASSAR Bachelor of Arts, 2007 Baylor University Waco, Texas Submitted to the Faculty Graduate Division College of Fine Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2010 ! ""! PLASTIC DYNAMISM IN PASTEL MODERNISM: JOSEPH STELLA’S FUTURIST COMPOSITION Thesis approved: ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Major Professor ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Frances Colpitt ___________________________________________________________________________ Rebecca Lawton, Curator, Amon Carter Museum ___________________________________________________________________________ H. Joseph Butler, Graduate Studies Representative For the College of Fine Arts ! """! Copyright © 2009 by Meredith Massar. All rights reserved ! "#! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to all those who have assisted me throughout my graduate studies at Texas Christian University. Thank you to my professors at both TCU and Baylor who have imparted knowledge and guidance with great enthusiasm to me and demonstrated the academic excellence that I hope to emulate in my future career. In particular I would like to recognize Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite for his invaluable help and direction with this thesis and the entire graduate school experience. Many thanks also to Dr. Frances Colpitt and Rebecca Lawton for their wisdom, suggestions, and service on my thesis committee. Thank you to Chris for the constant patience, understanding, and peace given throughout this entire process. To Adrianna, Sarah, Coleen, and Martha, you all have truly made this experience a joy for me. I consider myself lucky to have gone through this with all of you. Thank you to my brothers, Matt and Patrick, for providing me with an unending supply of laughter and support. -

Download the Painted Word Pdf Book by Tom Wolfe

Download The Painted Word pdf ebook by Tom Wolfe You're readind a review The Painted Word book. To get able to download The Painted Word you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this ebook on an database site. Ebook File Details: Original title: The Painted Word 112 pages Publisher: Picador; First edition (October 14, 2008) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780312427580 ISBN-13: 978-0312427580 ASIN: 0312427581 Product Dimensions:5.4 x 0.4 x 8.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 7111 kB Description: Americas nerviest journalist (Newsweek) trains his satirical eye on Modern Art in this masterpiece (The Washington Post)Wolfes style has never been more dazzling, his wit never more keen. He addresses the scope of Modern Art, from its founding days as Abstract Expressionism through its transformations to Pop, Op, Minimal, and Conceptual. The Painted... Review: If you have ever been confused, amused, or just plain confounded by abstract art, this book will make it very clear what its all about and what its not! Wolf described the forces, real and imagined, that brought this art movement to the fore. On the way you will smile and laugh at the goings on in the NY art world of the 50s and 60s. When you are... Book File Tags: tom wolfe pdf, modern art pdf, painted word pdf, art world pdf, new york pdf, abstract expressionism pdf, jackson pollock pdf, clement greenberg pdf, harold rosenberg pdf, contemporary art pdf, years ago pdf, bauhaus to our house pdf, pop art pdf, greenberg and rosenberg pdf, read this book pdf, leo steinberg pdf, art scene pdf, art history pdf, jasper johns pdf, art theory The Painted Word pdf ebook by Tom Wolfe in Arts and Photography Arts and Photography pdf books The Painted Word painted the word pdf the painted word fb2 painted the word ebook word painted the book The Painted Word The only bad thing I hate is how quickly it was over. -

The Modernist Iconography of Sleep. Leo Steinberg, Picasso and the Representation of States of Consciousness

60 (1/2021), pp. 53–73 The Polish Journal DOI: 10.19205/60.21.3 of Aesthetics Marcello Sessa* The Modernist Iconography of Sleep. Leo Steinberg, Picasso and The Representation of States of Consciousness Abstract In the present study, I will consider Leo Steinberg’s interpretation of Picasso’s work in its theoretical framework, and I will focus on a particular topic: Steinberg’s account of “Picas- so’s Sleepwatchers.” I will suggest that the Steinbergian argument on Picasso’s depictorial modalities of sleep and the state of being awake advances the hypothesis of a new way of representing affectivity in images, by subsuming emotions into a “peinture conceptuelle.” This operation corresponds to a shift from modernism to further characterizing the post- modernist image as a “flatbed picture plane.” For such a passage, I will also provide an overall view of Cubism’s main phenomenological lectures. Keywords Leo Steinberg, Pablo Picasso, Cubism, Phenomenology, Modernism 1. Leo Steinberg and Picasso: The Iconography of Sleep The American art historian and critic Leo Steinberg devoted relevant stages of his career to the interpretation of Picasso’s work. Steinberg wrote several Picassian essays, that appear not so much as disjecta membra but as an ac- tual corpus. In the present study, I will consider them in their theoretical framework, and I will focus on a particular topic: Steinberg’s account of “Pi- casso’s Sleepwatchers” (Steinberg 2007a). I will suggest that the Steinber- gian argument on Picasso’s depictorial modalities of sleep and the -

The Depiction of Law in the Bonfire of the Vanities

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1988 The Depiction of Law in the Bonfire of the Vanities Richard A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Posner, "The Depiction of Law in the Bonfire of the Vanities," 98 Yale Law Journal 1653 (1988). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Depiction of Law in The Bonfire of the Vanities Richard A. Posnert Tom Wolfe's best-selling novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, first pub- lished in 1987 and recently reissued in paperback, illustrates an aspect of the interaction between law and literature not discussed in my recent book on the law and literature movement, and indeed rather neglected (but per- haps benignly) by the movement as a whole. This is the depiction of law in popular literature.1 The popularity of Wolfe's novel and the salience of law in it make it a natural subject for consideration in a symposium on the treatment of law in popular culture. And if, as I shall argue, The Bonfire of the Vanities is not an especially rewarding subject for the study of law in popular culture after all, this may serve as a warning against unwarranted expectations concerning how much we can learn about law from its representation in popular culture, or about popular culture from its representation of law, or even about popular understanding of law. -

The State of Art Criticism

Page 1 The State of Art Criticism Art criticism is spurned by universities, but widely produced and read. It is seldom theorized, and its history has hardly been investigated. The State of Art Criticism presents an international conversation among art historians and critics that considers the relation between criticism and art history, and poses the question of whether criticism may become a university subject. Participants include Dave Hickey, James Panero, Stephen Melville, Lynne Cook, Michael Newman, Whitney Davis, Irit Rogoff, Guy Brett, and Boris Groys. James Elkins is E.C. Chadbourne Chair in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His many books include Pictures and Tears, How to Use Your Eyes, and What Painting Is, all published by Routledge. Michael Newman teaches in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and is Professor of Art Writing at Goldsmiths College in the University of London. His publications include the books Richard Prince: Untitled (couple) and Jeff Wall, and he is co-editor with Jon Bird of Rewriting Conceptual Art. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 1 Page 2 The Art Seminar Volume 1 Art History versus Aesthetics Volume 2 Photography Theory Volume 3 Is Art History Global? Volume 4 The State of Art Criticism Volume 5 The Renaissance Volume 6 Landscape Theory Volume 7 Re-Enchantment Sponsored by the University College Cork, Ireland; the Burren College of Art, Ballyvaughan, Ireland; and the School of the Art Institute, Chicago. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 2 Page 3 The State of Art Criticism EDITED BY JAMES ELKINS AND MICHAEL NEWMAN 08:52:27:10:07 Page 3 Page 4 First published 2008 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. -

The Painted Word

The Painted Word copyright © 1975 by Tom Wolfe PEOPLE DON’T READ THE MORNING NEWSPAPER, Marshall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. Too true, Marshall! Imagine being in New York City on the morning of Sunday, April 28, 1974, like I was, slipping into that great public bath, that vat, that spa, that, regional physiotherapy tank, that White Sulphur Springs, that Marienbad, that Ganges, that River Jordan for a million souls which is the Sunday New York Times. Soon I was submerged, weightless, suspended in the tepid depths of the thing, in Arts & Leisure, Section 2, page 19, in a state of perfect sensory deprivation, when all at once an extraordinary thing happened: I noticed something! Yet another clam-broth-colored current had begun to roll over me, as warm and predictable as the Gulf Stream ... a review, it was, by the Time’s dean of the arts, Hilton Kramer, of an exhibition at Yale University of “Seven Realists,” seven realistic painters . when I was jerked alert by the following: “Realism does not lack its partisans, but it does rather conspicuously lack a persuasive theory. And given the nature of our intellectual commerce with works of art, to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial—the 1 means by which our experience of individual works is joined to our understanding of the values they signify.” Now, you may say, My God, man! You woke up over that? You forsook your blissful coma over a mere swell in the sea of words? But I knew what I was looking at. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D. -

Ben Heller, Pioneering Collector of Abstract Expressionism: ‘There’S Nobody Else in That League’

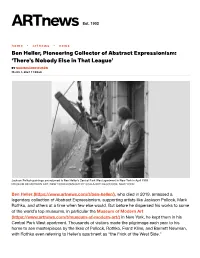

Est. 1902 home • ar tnews • news Ben Heller, Pioneering Collector of Abstract Expressionism: ‘There’s Nobody Else in That League’ BY MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN March 3, 2021 11:00am Jackson Pollock paintings are returned to Ben Heller's Central Park West apartment in New York in April 1959. MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK/LICENSED BY SCALA/ART RESOURCE, NEW YORK Ben Heller (https://www.artnews.com/t/ben-heller/), who died in 2019, amassed a legendary collection of Abstract Expressionism, supporting artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and others at a time when few else would. But before he dispersed his works to some of the world’s top museums, in particular the Museum of Modern Art (https://www.artnews.com/t/museum-of-modern-art/) in New York, he kept them in his Central Park West apartment. Thousands of visitors made the pilgrimage each year to his home to see masterpieces by the likes of Pollock, Rothko, Franz Kline, and Barnett Newman, with Rothko even referring to Heller’s apartment as “the Frick of the West Side.” When he began seriously collecting Abstract Expressionism during the ’50s, museums like MoMA largely ignored the movement. Heller rushed in headlong. “He wasn’t someone to say, ‘Let me take a gamble on this small picture so that I don’t really commit myself.’ He committed himself a thousand percent, which is what he believed the artists were doing,” Ann Temkin, chief curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA, said in an interview. Though Heller was never formally a board member at MoMA—“I was neither WASP-y enough nor wealthy enough,” he once recalled—he transformed the museum, all the while maintaining close relationships with artists and curators in its circle.