Download Original 301.48 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles University, Faculty of Arts East and Central European Studies

Charles University, Faculty of Arts East and Central European Studies Summer 2016 Jewish Images in Central European Cinema CUFA F 380 Instructor: Kevin Johnson Email: [email protected] Office Hours: by appointment Classes: Mon + Tue, 12.00 – 3.15, Wed 12.00 – 2.45, H201 (Hybernská 3, Prague 1) Course Description This course examines the portrayal of Jews and Jewish themes in the cinemas of Central Europe from the 1920s until the present. It considers not only depictions of Jews made by gentiles (sometimes with anti-Semitic undertones), but also looks at productions made by Jewish filmmakers aimed at a primarily Jewish audience. The selection of films is representative of the broader region where Czech, Slovak, Polish, Hungarian, Ruthenian, Ukranian, German, and Yiddish are (or were historically) spoken. Although attention will be given to the national-political context in which the films were made, most of the films by their very nature defy easy classification according to strict categories of statehood—this is particularly true for the pre-World War II Yiddish-language films. For this reason, the films will also be examined with an eye toward broader, transnational connections and global networks of people and ideas. Primary emphasis will be placed on two areas: (1) films that depict and document pre-Holocaust Jewish society in Central Europe, and (2) post-War films that seek to come terms with the Holocaust and the nearly absolute destruction of Jewish culture and tradition in the region. Weekly film screenings will be supplemented by theoretical readings related to the films or to concepts associated with them. -

Zalman Wendroff: the Forverts Man in Moscow

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

Ber Borochov's

Science in Context 20(2), 341–352 (2007). Copyright C Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0269889707001299 Printed in the United Kingdom Ber Borochov’s “The Tasks of Yiddish Philology” Barry Trachtenberg University at Albany Argument Ber Borochov (1881–1917), the Marxist Zionist revolutionary who founded the political party Poyle Tsien (Workers of Zion), was also one of the key theoreticians of Yiddish scholarship. His landmark 1913 essay, “The Tasks of Yiddish Philology,” was his first contribution to the field and crowned him as its chief ideologue. Modeled after late nineteenth-century European movements of linguistic nationalism, “The Tasks” was the first articulation of Yiddish scholarship as a discrete field of scientific research. His tasks ranged from the practical: creating a standardized dictionary and grammar, researching the origins and development of the language, and establishing a language institute; to the overtly ideological: the “nationalizing and humanizing” of the Yiddish language and its speakers. The essay brought a new level of sophistication to the field, established several of its ideological pillars, and linked Yiddish scholarship to the material needs of the Jewish people. Although “The Tasks” was greeted with a great deal of skepticism upon its publication, after his death, Borochov became widely accepted as the “founder” of modern Yiddish studies. “As long as a people remain ‘illiterate’ in their own language, one cannot yet speak of a national culture” (Borochov 1913, page 355 in this issue) When Ber Borochov’s manifesto “The Tasks of Yiddish Philology” appeared in 1913, few people could imagine that Yiddish was substantial enough to be the basis of a new scholarly discipline. -

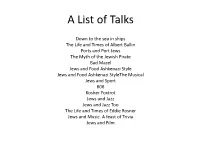

A List of Talks

A List of Talks Down to the sea in ships The Life and Times of Albert Ballin Ports and Port Jews The Myth of the Jewish Pirate Bad Mazel Jews and Food Ashkenazi Style Jews and Food Ashkenazi StyleThe Musical Jews and Sport 606 Kosher Foxtrot Jews and Jazz Jews and Jazz Too The Life and Times of Eddie Rosner Jews and Music. A feast of Trivia Jews and Film PORTS AND PORT JEWS The Port City was the gateway to settlement for Jews on their many migrations. Sometimes they stayed and settled, often they moved on to the hinterland. Before the advent of the aeroplane Port Cities were vital for the continuance of Jewish life. They enabled multi-continental networks to be set up, as well as providing a place of refuge and an escape hatch. Many of the places have now faded in our collective memory, but remain a vibrant part of the history of the last 2000 years. Tony will show you how those Port Jews adapted, survived, and even flourished. Including • The merchants of antiquity • The Atlantic triangle • Port Jews – Hull and Charleston • Odessa and Trieste – the Free Ports • City of Mud and Jews • The fishermen of Salonika - and Haifa • The last Port Jews The Myth of the Jewish Pirate Over the past few years an industry has grown up around the myth of the Jewish Pirate. There has been an exhibition in Marseille; a book called Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean; there are guided tours in Jamaica, and Jewish speakers regularly give talks on the subject. -

YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS DATES November 14, 1991 - January 9, 1992

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1991 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS DATES November 14, 1991 - January 9, 1992 ORGANIZATION Adrienne Mancia, Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art; Sharon Pucker Rivo, Executive Director, The National Center for Jewish Film, located at Brandeis University; and J. Hoberman, author and film critic, The Village Voice. SPONSOR Supported by a grant from The Nathan Cummings Foundation. Funding for the accompanying publication was provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The gallery exhibition is made possible by the Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Foundation in memory of Gladys and Saul Gwirtzman. CONTENT This first major retrospective of Yiddish cinema comprises films made in the United States and Europe from the 1920s through the 1980s. The exhibition includes melodramas, farces, tragedies, musical comedies, and documentaries that capture the talents of such international stars as Ida Kaminska, Lila Lee, Solomon Mikhoels, Molly Picon, and Maurice Schwartz. While only a fragment of the once vibrant world of Yiddish theater and cinema survives, these films depict the concerns and values of Yiddish culture and preserve the nuances of the Yiddish language. Chronicling the struggle for Jewish identity on both sides of the Atlantic, the exhibition features Yiddle with His Fiddle (1936) and The Dybbuk (1937), from Poland; Jewish Luck (1925) and The Return of Nathan Beck (1934), from Russia; East and Hest (1923), from Austria; and Uncle Moses (1932), Tevye (1939), and God, Man, and Devil (1950), from the United States. Several recent films, including Brussels Transit (1980), from Belgium, and If They Give, Take (1983), from Israel, offer a contemporary glimpse of Yiddish-language drama. -

Jewish Experience on Film an American Overview

Jewish Experience on Film An American Overview by JOEL ROSENBERG ± OR ONE FAMILIAR WITH THE long history of Jewish sacred texts, it is fair to characterize film as the quintessential profane text. Being tied as it is to the life of industrial science and production, it is the first truly posttraditional art medium — a creature of gears and bolts, of lenses and transparencies, of drives and brakes and projected light, a creature whose life substance is spreadshot onto a vast ocean of screen to display another kind of life entirely: the images of human beings; stories; purported history; myth; philosophy; social conflict; politics; love; war; belief. Movies seem to take place in a domain between matter and spirit, but are, in a sense, dependent on both. Like the Golem — the artificial anthropoid of Jewish folklore, a creature always yearning to rise or reach out beyond its own materiality — film is a machine truly made in the human image: a late-born child of human culture that manifests an inherently stubborn and rebellious nature. It is a being that has suffered, as it were, all the neuroses of its mostly 20th-century rise and flourishing and has shared in all the century's treach- eries. It is in this context above all that we must consider the problematic subject of Jewish experience on film. In academic research, the field of film studies has now blossomed into a richly elaborate body of criticism and theory, although its reigning schools of thought — at present, heavily influenced by Marxism, Lacanian psycho- analysis, and various flavors of deconstruction — have often preferred the fashionable habit of reasoning by decree in place of genuine observation and analysis. -

YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS Fact Sheet

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1991 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS DATES November 14, 1991 - January 9, 1992 ORGANIZATION Adrienne Mancia, Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art; Sharon Pucker Rivo, Executive Director, The National Center for Jewish Film, located at Brandeis University; and J. Hoberman, author and film critic, The Village Voice. SPONSOR Supported by a grant from The Nathan Cummings Foundation. Funding for the accompanying publication was provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The gallery exhibition is made possible by the Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Foundation in memory of Gladys and Saul Gwirtzman. CONTENT This first major retrospective of Yiddish cinema comprises films made in the United States and Europe from the 1920s through the 1980s. The exhibition includes melodramas, farces, tragedies, musical comedies, and documentaries that capture the talents of such international stars as Ida Kaminska, Lila Lee, Solomon Mikhoels, Molly Picon, and Maurice Schwartz. While only a fragment of the once vibrant world of Yiddish theater and cinema survives, these films depict the concerns and values of Yiddish culture and preserve the nuances of the Yiddish language. Chronicling the struggle for Jewish identity on both sides of the Atlantic, the exhibition features Yiddle with His Fiddle (1936) and The Dybbuk (1937), from Poland; Jewish Luck (1925) and The Return of Nathan Beck (1934), from Russia; East and Hest (1923), from Austria; and Uncle Moses (1932), Tevye (1939), and God, Man, and Devil (1950), from the United States. Several recent films, including Brussels Transit (1980), from Belgium, and If They Give, Take (1983), from Israel, offer a contemporary glimpse of Yiddish-language drama. -

AJS Review Cinema Studies/Jewish Studies, 2011–2013

AJS Review http://journals.cambridge.org/AJS Additional services for AJS Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Cinema Studies/Jewish Studies, 2011–2013 Naomi Sokoloff AJS Review / Volume 38 / Issue 01 / April 2014, pp 143 - 160 DOI: 10.1017/S0364009414000075, Published online: 02 May 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0364009414000075 How to cite this article: Naomi Sokoloff (2014). Cinema Studies/Jewish Studies, 2011–2013 . AJS Review, 38, pp 143-160 doi:10.1017/S0364009414000075 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AJS, IP address: 128.95.104.66 on 26 May 2014 AJS Review 38:1 (April 2014), 143–160 © Association for Jewish Studies 2014 doi:10.1017/S0364009414000075 REVIEW ESSAY CINEMA STUDIES/JEWISH STUDIES, 2011–2013 Naomi Sokoloff In an era of massive university budget cuts and pervasive malaise regarding the future of the humanities, cinema and media studies continue to be a growth industry. Many academic fields have been paying increasing attention to film, in terms of both curriculum development and research. Jewish studies is no excep- tion. Since 2011, a boom in publications has included a range of new books that deal with Jews on screen, Jewish themes in cinema, and the construction of Jewish identity through film. To assess what these recent titles contribute to Jewish cinema studies, though, requires assessing the parameters of the field—and that is no easy task. The definition of what belongs is as elastic as the boundaries of Jewish identity and as perplexing as the perennial question, who is a Jew? Conse- quently, the field is wildly expansive, potentially encompassing the many geo- graphical locales where films on Jewish topics have been produced as well as the multiple languages and cinematic traditions within which such films have emerged. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release October 1991 YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS November 14, 1991 - January 12, 1992 The first major exhibition of Yiddish films made in Europe and the United States from the 1920s through the 1980s opens at The Museum of Modern Art on November 14, 1991. The films featured in YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS depict the concerns and values of Yiddish culture and preserve the nuances of the Yiddish language. The exhibition continues through January 12, 1992. YIDDISH FILM BETWEEN TWO WORLDS includes melodramas, farces, tragedies, musical comedies, and documentaries that capture the talents of such international stars as Ida Kaminska, Solomon Mikhoels, Molly Picon, Ludwig Satz, and Maurice Schwartz, America's foremost Yiddish actor. Chronicling the struggle for Jewish identity on both sides of the Atlantic, the exhibition features many classics of Yiddish cinema: Yiddle with His Fiddle (1936; starring Molly Picon) and The Dybbuk (1937), from Poland; Jewish Luck (1925) and The Return of Nathan Becker (1932), from the Soviet Union; fast and West (1923), from Austria; and Uncle Moses (1932; starring Maurice Schwartz), Tevye (1939), and God, Man, and Devil (1950), from the United States. Several recent films, including Brussels Transit (1980), from Belgium, and Everything's for You (1989) and Hester Street (1975), from the United States, offer a glimpse of contemporary Yiddish-language drama. While only a fragment of the once vibrant world of Yiddish theater and cinema survives, these films are invaluable for their representation of a - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 popular culture that flourished in the period 1911 to 1948 in Poland, the Soviet Union, Austria, and the United States. -

Yiddish in the Andes. Unbearable Distance, Devoted Activists and Building Yiddish Culture in Chile Mariusz Kałczewiak

Humanwissenschaftliche Fakultät Mariusz Kałczewiak Yiddish in the Andes Unbearable distance, devoted activists and building Yiddish culture in Chile Suggested citation referring to the original publication: Jewish Culture and History (2019) DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/1462169X.2019.1658460 ISSN (print) 1462-169X ISSN (online) 2167-9428 Postprint archived at the Institutional Repository of the Potsdam University in: Postprints der Universität Potsdam Humanwissenschaftliche Reihe ; 571 ISSN 1866-8364 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-435064 DOI https://doi.org/10.25932/publishup-43506 JEWISH CULTURE AND HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/1462169X.2019.1658460 Yiddish in the Andes. Unbearable distance, devoted activists and building Yiddish culture in Chile Mariusz Kałczewiak Slavic Studies Department, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This article elucidates the efforts of Chilean-Jewish activists to Received 22 December 2018 create, manage and protect Chilean Yiddish culture. It illuminates Accepted 7 May 2019 how Yiddish cultural leaders in small diasporas, such as Chile, KEYWORDS worked to maintain dialogue with other Jewish centers. Chilean Yiddish culture; Chile; Latin culturists maintained that a unique Latin American Jewish culture America; Yiddish culturism; existed and needed to be strengthened through the joint efforts Jewish networking of all Yiddish actors on the continent. Chilean activists envisioned a modern Jewish culture informed by both Eastern European influences and local Jewish cultural production, as well as by exchanges with non-Jewish Latin American majority cultures. In 1933, Yiddish writer Moyshe Dovid Guiser arrived in the Chilean capital of Santiago.1 Frustrated with the situation in Argentina where he had lived for the past nine years, Guiser decided to make a new start on the other side of the Andes. -

Interracial Unionism in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and the Development of Black Labor Organizations, 1933-1940

THEY SAW THEMSELVES AS WORKERS: INTERRACIAL UNIONISM IN THE INTERNATIONAL LADIES’ GARMENT WORKERS’ UNION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF BLACK LABOR ORGANIZATIONS, 1933-1940 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Julia J. Oestreich August, 2011 Doctoral Advisory Committee Members: Bettye Collier-Thomas, Committee Chair, Department of History Kenneth Kusmer, Department of History Michael Alexander, Department of Religious Studies, University of California, Riverside Annelise Orleck, Department of History, Dartmouth College ABSTRACT “They Saw Themselves as Workers” explores the development of black membership in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) in the wake of the “Uprising of the 30,000” garment strike of 1933-34, as well as the establishment of independent black labor or labor-related organizations during the mid-late 1930s. The locus for the growth of black ILGWU membership was Harlem, where there were branches of Local 22, one of the largest and the most diverse ILGWU local. Harlem was also where the Negro Labor Committee (NLC) was established by Frank Crosswaith, a leading black socialist and ILGWU organizer. I provide some background, but concentrate on the aftermath of the marked increase in black membership in the ILGWU during the 1933-34 garment uprising and end in 1940, when blacks confirmed their support of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and when the labor-oriented National Negro Congress (NNC) was irrevocably split by struggles over communist influence. By that time, the NLC was also struggling, due to both a lack of support from trade unions and friendly organizations, as well as the fact that the Committee was constrained by the political views and personal grudges of its founder. -

List of Refernces

SEWING THE SEEDS OF STATEHOOD: GARMENT UNIONS, AMERICAN LABOR, AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL, 1917-1952 By ADAM M. HOWARD A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2003 Copyright 2003 by Adam M. Howard ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research and writing of this dissertation, spanning a period of five years, required assistance and understanding from a variety of individuals and groups, all of whom I wish to thank here. My advisor, Robert McMahon, has provided tremendous encouragement to me and this project since its first conception during his graduate seminar in diplomatic history. He instilled in me the courage necessary to attempt bridging three subfields of history, and his patience, insight, and willingness to allow his students to explore varied approaches to the study of diplomatic history are an inspiration. Robert Zieger, in whose research seminar this project germinated into a more mature study, offered tireless assistance and essential constructive criticism. Additionally, his critical assessments of my evidence and prose will influence my writing in the years to come. I also will always remember fondly our numerous conversations regarding the vicissitudes of many a baseball season, which served as needed distractions from the struggles of researching and writing a dissertation. Ken Wald has consistently backed my work both intellectually and financially through his position as the Chair of the Jewish Studies Center at the University of Florida and as a member of my committee. His availability and willingness to offer input and advice on a variety of topics have been most helpful in completing this study.