The African E-Journals Project Has Digitized Full Text of Articles of Eleven Social Science and Humanities Journals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276087553 Truncation of SOme Akan Personal Names Article in Gema Online Journal of Language Studies · February 2015 DOI: 10.17576/GEMA-2015-1501-09 CITATION READS 1 180 1 author: Kwasi Adomako University of Education, Winneba 8 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Akan loanwords in Ga-Dangme sub-family View project All content following this page was uploaded by Kwasi Adomako on 31 May 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 143 Volume 15(1), February 2015 Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names Kwasi Adomako [email protected] University of Education, Winneba, Ghana ABSTRACT This paper examines some morphophonological processes in Akan personal names with focus on the former process. The morphological processes of truncation of some indigenous personal names identified among the Akan (Asante) ethnic group of Ghana are discussed. The paper critically looks at some of these postlexical morpheme boundary processes in some Akan personal names realized in the truncated form when two personal names interact. In naming a child in a typical Akan, specifically in Asante‟s custom, a family name is given to the child in addition to his/her „God-given‟ name or day-name. We observe truncation and some phonological processes such as vowel harmony, compensatory lengthening, etc. at the morpheme boundaries in casual speech context. These morphophonological processes would be analyzed within the Optimality Theory framework where it would be claimed that there is templatic constraint that demands that the base surname minimally surfaces as disyllable irrespective of the syllable size of the base surname. -

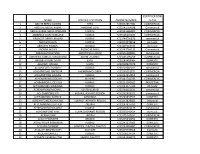

Index Number Name 101001 Agbodza Thomas Kwashie

DOMESTIC NOVDEC 2016 RESULTS INDEX NUMBER NAME 101001 AGBODZA THOMAS KWASHIE 111021 AMEXO GRANT FRANCIS YAW 301040 MOHAMMED ALHASSAN 201002 ABDEEN HASSAN 401001 ABDUL MAJEED ABDUL SOMED 101002 ABDUL RAHAMAN AHMED 101003 ABDUL RAZAK KASSUM 401002 ABDULAI ADAM MARSHAL 111001 ABEKAH JOSHUA 111002 ABOAGYE CHRISTOPHER 301001 ABOAGYE BENARD 101004 ABOAGYE OSBORN DUODU 111003 ABOAGYE PETER 101005 ABOAGYE WILLIAM 201003 ABU SADIQUE 201004 ABUBAKARI HANIF 101006 ABUGRE NATHANIEL ATINGA 401003 ABUKARI ALHASSAN 301002 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN 101007 ACHIANGBON KWABLA 201005 ACKAH PADMORE 301003 ACKAH SAMUEL 101008 ACQUAH BENJAMIN 111004 ACQUAH DICKSON 201006 ACQUETE ASAREWI PAUL 401004 ADAM ABDUL HANAN 201007 ADAMS KOFI 401005 ADAPAH ISAAC KABILLAH 301004 ADDAE ALEXANDER 101010 ADDAE DOUGLAS 101011 ADDO FRANCIS SACKITEY 111005 ADDO KINGSLEY FIANKO 101012 ADDO OBED 201008 ADJEI DAVID 201009 ADJEI FRANCIS 201097 ADJEI JOSEPH 101013 ADJOMAH JOSEPH 101014 ADOARI AWUMBE EUGENE 101015 ADOMAKO DANIEL 111006 ADU KINGSLEY ASIEDU 201011 ADU ERNEST 201012 ADU SAMUEL 101017 ADUKPO DIVINE 111007 ADZAGBA GODKNOWS 101018 AFADEMOR JOSEPH YAW 101019 AFERI SIAW STEPHEN 101214 AFUM EDWARD 111008 AGBANATOR FUTURE 101021 AGBAVOR SIMON 111009 AGBELI JOSEPH KOMLA 101022 AGBEMADE SIMON 111011 AGBODEKA GODSWAY 111012 AGBODZA CHARLES TAWIAH 101026 AGBODZA SAMUEL 301005 AGBOSHIE DAVID 101027 AGORKOR PROSPER 401006 AGURI MAMUDU 101028 AGYAKWAH JOSEPH OFOSU 201014 AGYAPONG BOAME GABRIEL 201015 AGYAPONG FRANK 111013 AGYEI ERIC ANOKYE 201016 AGYEI OLIVER 111014 AGYEMANG EMMANUEL KOJO -

Nana Yaa Asantewaa, the Queen Mother of Ejisu: the Unsung

NANA YAA ASANTEWAA, THE QUEEN MOTHER OF EJISU: THE UNSUNG HEROINE OF FEMINISM IN GHANA BY NANA POKUA WIAFE MENSAH A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto ©Copyright by Nana Pokua Wiafe Mensah (2010) NANA YAA ASANTEWAA, THE QUEEN MOTHER OF EJISU: THE UNSUNG HEROINE OF FEMINISM IN GHANA Nana Pokua Wiafe Mensah Master of Arts Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the life story of Nana Yaa Asantewaa and its pedagogical implications for schooling and education in Ghana and Canada. Leadership role among women has been a topic in many debates for a long period. For many uninformed writers about the feminist struggles in Africa, Indigenous African women are docile bodies with little or no agencies and resistance power. However, the life history of Nana Yaa Asantewaa questions the legitimacy and accuracy of this misrepresentation of Indigenous African women. In 1900, Yaa Asantewaa led the Ashanti community in a war against the British imperial powers in Ghana. The role Yaa Asantewaa played in the war has made her the legend in history of Ghana and the feminist movement in Ghana. This dissertation examines the traits of Yaa Asantewaa and the pedagogic challenges of teaching Yaa Asantewaa in the public schools in Ghana and Canada. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to four important people in my life. Nana Wiafe Akenten III and Mrs. -

Name Specific Location Phone Number Certification Class

CERTIFICATION NAME SPECIFIC LOCATION PHONE NUMBER CLASS 1 ABAYIE BERKO AKWASI TEPA +233542854981 COMMERCIAL 2 ABDULAI ABDUL-RAZAK MABANG TEPA +233242764598 Commercial 3 ABDUL-KARIM ABDUL RAHMAN KUMASI +233243286809 COMMERCIAL 4 ABEBRESE DJAN ROWLAND KUMASI +233506264844 COMMERCIAL 5 ABOAGYE DANIEL AKWASI KUMASI +233244756870 commercial 6 ABOAGYE ELVIS KUMASI +233242978816 domestic 7 ABOAGYE KWAME BEKWAI +233207163334 domestic 8 ABORAH MOSES BUOHO KUMASI +233247764133 Commercial 9 ABRAHAM BOATENG AKROPONG KUMASI +233246188985 commercial 10 ABROKWA SAMUEL KORANTENG ADUM , KUMASI +233246590209 COMMERCIAL 11 ABUGRI AYAGRI DAVID EJISU +233249458064 DOMESTIC 12 ABUKARI INUSAH EJURA +233200937079 DOMESTIC 13 ACCOMFORD RICHARD KUMASI +233201682011 commercial 14 ACHEAMPONG BAFFOUR AHENEMAKOKOBEN +233248253831 COMMERCIAL 15 ACHEAMPONG AKWASI KUMASI +233242954852 commercial 16 ACHEAMPONG GIDEON MAAKRO +233241744743 COMMERCIAL 17 ACHEAMPONG JOE ELLIS KUMASI +233244560405 INDUSTRIAL 18 ACHEAMPONG KWABENA KUMASI +233243375366 domestic 19 ACHEAMPONG MICHAEL ASAFO-KUMASI +233244102431 commercial 20 ACHEAMPONG NTI KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION +233262428325 commercial 21 ACHEAMPONG PATRICK KONONGO +233249833553 DOMESTIC 22 ACHEAMPONG RICHMOND KUMASI ASHANTI REGION +233243828683 Industrial 23 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN OBUASI +233247937033 DOMESTIC 24 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM KUMASI +233203321176 commercial 25 ACHEAMPONG YAW KUMASI,ASHANTI REGION +233265042424 domestic 26 ACKAH JOHN OBUASI +233275247651 COMMERCIAL 27 ACKAH PADMORE BEKWAI +233245340252 DOMESTIC 28 ACKAH PHILIP -

Asante Traditional Leadership and the Process

ASANTE TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROCESS OF EDUCATIONAL CHANGE A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY OWUSU-KWARTENG August 2005 © 2005 NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY OWUSU-KWARTENG All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled ASANTE TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROCESS OF EDUCATIONAL CHANGE By NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY OWUSU-KWARTENG has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and the College of Education by William Stephen Howard Professor of Telecommunication James Heap Dean, the College of Education OWUSU-KWARTENG, NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY. Ph.D. August 2005 Educational Studies ASANTE TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROCESS OF EDUCATIONAL CHANGE (222 pp) Director of Dissertation: William Stephen Howard, Ph.D. Abstract This study lies at the intersection of contemporary research on leadership and concerns for the performance of recent African leaders and theme of participation. It utilizes qualitative approaches to examine the issue of leadership and stakeholder participation in the role of Asante traditional leadership and the process of educational change in Ghana during the last quarter of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty- first centuries and the representations that such participation holds for the rest of the country and Africa in the quest for relevant education systems, leadership functions and expectations of stakeholders. The call of the Asantehene (King of Asante), Otumfuo Osei Tutu II at his installation that improved and quality formal education should be a criterion of assessment for his reign; the subsequent establishment of the Otumfuo Education Fund and Offinsoman Education Trust Fund provided the background to formulate the study. -

Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names

GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 143 Volume 15(1), February 2015 Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names Kwasi Adomako [email protected] University of Education, Winneba, Ghana ABSTRACT This paper examines some morphophonological processes in Akan personal names with focus on the former process. The morphological processes of truncation of some indigenous personal names identified among the Akan (Asante) ethnic group of Ghana are discussed. The paper critically looks at some of these postlexical morpheme boundary processes in some Akan personal names realized in the truncated form when two personal names interact. In naming a child in a typical Akan, specifically in Asante‟s custom, a family name is given to the child in addition to his/her „God-given‟ name or day-name. We observe truncation and some phonological processes such as vowel harmony, compensatory lengthening, etc. at the morpheme boundaries in casual speech context. These morphophonological processes would be analyzed within the Optimality Theory framework where it would be claimed that there is templatic constraint that demands that the base surname minimally surfaces as disyllable irrespective of the syllable size of the base surname. The relatively high ranking of this minimality constraint, we claim in this paper, forces the application of the compensatory lengthening rule to ensure satisfaction of that constraint in the truncated forms. Keywords: personal names; Akan; optimality theory; morphology; truncation INTRODUCTION This paper studies the morphophonology of some indigenous Akan (Asante) personal names (henceforth APN), which generally falls under onomastics. The present study focuses on the analysis of how these personal names are realized at the phonetic level of the Akan grammar. -

Kente Cloth Weaving Among the Asante in Ghana a West African Example of Gender and Role Change Resistance

University of Al berta Kente Cloth Weaving among the Asante in Ghana A West African Example of Gender and Role Change Resistance Mari Elizabeth Bergen O A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Textiles and Clothing Department of Human Ecology Edmonton, Alberta Fall 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*m ofcarda du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services senrices bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 ûtrawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire' prêter, distncbuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantieIs may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Kente doth weaving on the namw4p West Afn'can loom is traditionally a male role among the Asante in Ghana. 1 conducted forma1 and informal intewiews with residents of al1 age groups, in Bonwire, to soli& opinion on why or why not women should weave in the village. -

Editor's Introduction

Capturing Students’ Target Language Exposure Collaboratively, on Video – The Akan (Twi) Example Seth Antwi Ofori University of Wisconsin – Madison Abstract: The video project at the center of this paper is one of the strategies the author has been utilizing in teaching Akan as a foreign language aimed at reinforcing aspects of Akan covered in a given semester, specifically as students transition through different levels of language instruction and acquisition or go home on vacation. The significance of this project lies in the fact that it promotes language documenta- tion and material development in less-documented languages, and also, in the fact that it gives foreign language learners the opportunity to reinforce their target language exposure on vacation, or as they transition through the different levels of study, because each student gets a copy of the video to watch with their communities outside of the classroom. 1. Introduction The non-availability of videos for teaching Akan as a second language, coupled with students’ inability to retain target language materials, largely as a result of a long school vacation during which they have no access to their new language, are problems that led to this idea of requiring and organizing students each semester to cap- ture much of their language exposure on video. The video at the cen- ter of this article is worth sharing because, while there have been countless articles, dissertations (and even books) on the various me- thods of teaching a foreign language through video (Morris 2000, Steele and Johnson 2000, Rhodes and Pufahl 2004), there have been virtually none on students of less commonly taught, funded, and do- cumented languages working together each semester to document their target language exposure through video. -

Name Phone Number Location Certification Class 1

NAME PHONE NUMBER LOCATION CERTIFICATION CLASS 1 ABDULAI BASHIRU BEN KUMASI DOMESTIC 2 ABDULAI MOHAMMED KUMASI DOMESTIC 3 ABOAGYE DANIEL AKWASI 244756870 KUMASI COMMERCIAL 4 ABOAGYE ELVIS 0242978816/0233978816 KUMASI DOMESTIC 5 ABOAGYE KWAME 207163334 KUMASI DOMESTIC 6 ABRAHAM BOATENG 246188985 AKROPONG, KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION COMMERCIAL 7 ABREFAH NOAH KUMASI DOMESTIC 8 ABROKWA, SAMUEL KORANTENG 0246590209 ADUM NEAR POST OFFICE, KUMASI COMMERCIAL 9 ABUBEKR COLLINS 508895569 NEW NYAMEREREYERE COMMERCIAL 10 ACCOMFORD RICHARD 244926482 KENTIKRONO COMMERCIAL 11 ACHEAMPONG AKWASI 208063734 AMAKOM-STADIUM COMMERCIAL 12 ACHEAMPONG JOE ELLIS 0244560405 ADUM, KUMASI INDUSTRIAL 13 ACHEAMPONG KWABENA 243375366 NEW SUAME KUMASI DOMESTIC 14 ACHEAMPONG MICHAEL 0244102431 ASAFO-KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION COMMERCIAL 15 ACHEAMPONG NTI 262428325 KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION COMMERCIAL 16 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN 247937033 OBUASI NEW ESTATE DOMESTIC 17 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM 203321176 KUMASI COMMERCIAL 18 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM 0249691088 MAKRO, ABUAKWA, ASHANTI COMMERCIAL 19 ACHEAMPONG YAW 265042424 KUMASI,ASHANTI REGION DOMESTIC 20 ACQUAH CLEMENT 0243505887 BOHYEN, KUMASI, ASHANTI COMMERCIAL 21 ACQUAH SAMUEL 0208124324 AMAOKOM, OBUASI DOMESTIC 22 ADADE NELSON KWAME 272932398 ASOKORE-MAMPONG INDUSTRIAL 23 ADAMS ABDELAH KUMASI DOMESTIC 24 ADAMS BERNARD 0207612895 ATONSU SAWUA-AWIEM COMMERCIAL 25 ADAMS JAMES KOFI 0244616357 KUMASI,ASHANTI REGION DOMESTIC 26 ADARKWAH SAMUEL 543586905 OBUASI NEW ESTATE DOMESTIC 27 ADDAI EMMANUEL KWAKU 0244010115 KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION COMMERCIAL -

End-Of-Life Care, Death and Funerals of the Asante: an Ethical and Theological Vision

End-of-life care, death and funerals of the Asante: An ethical and theological vision Author: Emmanuel Adu Addai Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:106929 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2016 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. THESIS TITLE END-OF-LIFE CARE, DEATH AND FUNERALS OF THE ASANTE: AN ETHICAL AND THEOLOGICAL VISION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF LICENTIATE IN SACRED THEOLOGY (BIOETHICS) BY EMMANUEL ADU ADDAI AT BOSTON COLLEGE MAY 3, 2016 END-OF-LIFE CARE, DEATH, AND FUNERALS OF THE ASANTES: AN ETHICAL AND THEOLOGICAL VISION ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In writing this thesis I have been assisted by the advice and practical directions of a number of people. But I wish to signal my particular gratitude to two great individuals without whose help this work would not have been completed. In the first place I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Professors Melissa Kelley and Lisa Sowle Cahill, my directors, for their kindness to me for accepting the invitation to work with me and reading through the manuscript and for offering awesome suggestions. I wish to express my heartfelt thanks to the Research Librarian at School of Theology and Ministry Library, Steve Dalton, for his wonderful assistance throughout my two years stay at Boston College, and in particular to this thesis. Also I express my profound gratitude to my Archbishop, His Grace Justice Yaw Anokye, Archbishop of Kumasi for his care and love and also giving me the opportunity to do my graduate studies in this great University, Boston College. -

Kwadwo Amankwah Antwi March 23, 1961 - March 31, 2015

PHONE: (972) 562-2601 Kwadwo Amankwah Antwi March 23, 1961 - March 31, 2015 Kwadwo Amankwah Antwi, age 54, of McKinney, Texas, passed away March 31, 2015. Kwadwo was born March 23, 1961, in Ghana, Africa, to Isaac C. and Mary E. (Kankam) Antwi. In 1977 he completed his high school education at Mfantsipim School in Ghana (MOBA 77) and continued to Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana where he graduated with a bachelor of science degree in social sciences, majoring in economics. He graduated in 1997 from Southern Methodist University in Dallas with a Master’s in Business Administration. Kwadwo formed his own business and called it Global Endeavors, LLC. He is survived by his sons, Kevin Antwi of McKinney, Texas and David Antwi of Houston, Texas; and siblings, Christiana Aning, Juliana Owusu, Robert Antwi, Alice Kyere, Ernest Kofi Antwi, Owusu Sekyere Antwi, Kwabena Antwi, Freda Antwi, Doris Kokuma, Muriel Antwi, and Adwoa Antwi. He was preceded in death by his parents, sister, Georgia Antwi, and brother, Kwasi Antwi. A funeral service will be held at 2:00 p.m., Saturday, April 11, 2015, at Turrentine-Jackson-Morrow Chapel in Allen, Texas. Entombment will follow at Ridgeview Memorial Park in Allen. The family will receive friends during a visitation from 7:00 – 9:00 p.m., Friday evening at the funeral home. Memorials Cousin Amanks - Words cannot express the level of pain we feel, as a result of your premature departure. This vacuum can never be filled!! You were always the consistent source of reassurance and calmness....Although you have departed, your memory will forever be entrenched in our hearts ..Rest in Perfect Peace my Brother! And may the good Lord keep you till we meet again.. -

Creation in the Image of God: Human Uniqueness from the Akan Religious Anthropology to the Renewal of Christian Anthropology Eric Baffoe Antwi

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 1-1-2016 Creation in the Image of God: Human Uniqueness From the Akan Religious Anthropology to the Renewal of Christian Anthropology Eric Baffoe Antwi Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Antwi, E. (2016). Creation in the Image of God: Human Uniqueness From the Akan Religious Anthropology to the Renewal of Christian Anthropology (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1509 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. CREATION IN THE IMAGE OF GOD: HUMAN UNIQUENESS FROM THE AKAN RELIGIOUS ANTHROPOLOGY TO THE RENEWAL OF CHRISTIAN ANTHROPOLOGY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Rev. Eric Baffoe Antwi May 2016 Copyright by Rev. Eric Baffoe Antwi 2016 CREATION IN THE IMAGE OF GOD: HUMAN UNIQUENESS FROM THE AKAN RELIGIOUS ANTHROPOLOGY TO THE RENEWAL OF CHRISTIAN ANTHROPOLOGY By Rev. Eric Baffoe Antwi Approved February 10, 2016 ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Elochukwu E. Uzukwu, C.S.Sp Dr. Gerald Boodoo Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ Dr. Maureen R. O’Brien Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. James Swindal, Dean, McAnulty Dr. Maureen R. O’Brien Graduate School of Liberal Arts Chair, Department of Theology Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of Theology iii ABSTRACT CREATION IN THE IMAGE OF GOD: HUMAN UNIQUENESS FROM THE AKAN RELIGIOUS ANTHROPOLOGY TO THE RENEWAL OF CHRISTIAN ANTHROPOLOGY By Rev.