Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Din to the Akan Naming Ceremony

“Odenkyem da nsuo mu nso ohome mframa” “The Crocodile lives in water, but breathes air not water” (know your identity, know your function) Din To The Akan Naming Ceremony The name is an essential component of the spiritual anatomy of the Afurakani/Afuraitkaitnit (African) person. It confirms identity. Thus, from time immemorial Afurakanu/Afuraitkaitnut (Africans) have taught, with respect to the sacredness of the name, "Truly, without a name the Afurakani/Afuraitkaitnit (African) human does not exist." The name is a group of sounds---sounds/vibrations grouped together in a unique way. Power from the sounds/vibrations of a properly given name moves throughout the spirit of the Afurakani/Afuraitkaitnit (African) person when heard or spoken. The spirit responds to this power, stirring within the person an awareness of their unique purpose in life and of the potential they possess to carry out that purpose. As the purpose of one's life is given to him or her by The Supreme Being before birth, we recognize our unique purpose, our destiny in Creation, to be a divine purpose, a divine destiny. We define our purpose, our destiny, as the divine function we are to execute in this world. Thus the name, the power-carrying indicator of our divine function, has always been and continues to be most sacred to us. When heard or spoken, it aligns us with our Divine nature. It is within this context that the naming ceremonies of Afurakani/Afuraitkaitnit (African) people must be viewed. The din to (naming ceremony) of the Akan people of West Afuraka/Afuraitkait (Africa) is expressive of these principles. -

Directory of Church Members

CENTRAL BUSINESS SCHOOL BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN AGRIBUSINESS MANAGEMENT AFFUL, DESMOND ANTO-DUAH, JOSEPH ANTWI, PRINCE BAAPEGNE, ALFRED BROBBEY, ELISHA COLE, ADELAIDE YEBOAH DANQUAH, JAMES DWOMMOH-MENSAH, HENDRICK EYISON, PATRICK GARIBA, NANA AYISHA KEDADOR, GIDEON KONLAN, ABRAHAM BIMIIB KYEI, SMITH NKOKOLO MASSAMBA, ANGELTY OBENG-AGYEI, MICHAEL OGAR, MARY OCHUOLE CENTRAL BUSINESS SCHOOL BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN AGRIBUSINESS MANAGEMENT (WEEKEND) ARHIN , JOHN ARTHUR, MARK RAYMOND FIAGBOR, MABEL KUUDAAR, EUNICE NII-OBLIE OKAI, SAMUEL CENTRAL BUSINESS SCHOOL BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN BANKING AND FINANCE ABDULAI, RASHIDA ASAMOAH-TOPEN, LOIS SAFOA ADAMS, EMMA ASANTE, PRINCE ADDAI, CHARLOTTE DZIFA ASANTE-BOAMAH, LISA ADDO, DELIGHT YAYRA ASIAMAH, CHARLES OBENG ALHASSAN , ABDUL GAFARU ASSEFUAH, WILFRED ALLOTEY, JENNIFER ADUKWEI ATEAH, OHEMAA AKOSUA AMANKRAH, PERPETUAL BAKU, EVELYN AMISSAH, AGNES BESSEY, BERTHA KORKOR AMPOFO, ALFRED GYAKYI BLAY, EMMA CENTRAL BUSINESS SCHOOL BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN BANKING AND FINANCE BONNEY, MAVIS BONZUA BONSU, GLADYS OSEI DIAWUO, EMMANUELLA KYERE DOGBE, HARRIET DOMFEH, BELINDA MAAME AGYEIWAA ESHUN, FELICITY NKUMAH FRIMPONG, JERRY ASIEDU JOHN HILL, JOHN JOHN-CHUKWU, PATIENCE KOTEY, SEPHIATU NAA-DEI KUSI, CAROLINE ADUSA LARTEY, EDWARD MEBAH, JOYCELINE NEIZER, ESSUAH NIMAKO, EMELIA OSABUTEY, CANDICE LADGER OWUSU-ANTWI, KWABENA PARKINS, ADRIANA PREMPEH, EMMANUELLA KONADU QUAINOO, PIUS FIIFI QUAYSON, ISAAC ACHEAMPONG SMITH KOOMSON, BERYL TANNOR, ADWOA BOADUWAA TETTEH, EDWARD TORDMAN, EMMANUELLA CENTRAL BUSINESS SCHOOL BACHELOR -

Kinship and Change in Kumasi, Ghana

Legacies: Kinship and Change in Kumasi, Ghana By Carmen Asha Nave A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright Carmen Nave 2015 Legacies: Kinship and Change in Kumasi Ghana Carmen Asha Nave Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This study situates current kinship and inheritance practices among the matrilineal Asante within an analysis of cultural and legal change. Based on 18 months of fieldwork in Kumasi, Ghana, I analyze matrilineal kinship and marriage by considering the ways in which ongoing kin relations influence inheritance decision-making in conjunction with broadly shared notions of custom or law. I critically examine a supposed schism between “traditional” and “modern” inheritance to show various points of convergence between past and present notions of inheritance and kinship. I show that people incorporate the principles of both state inheritance law and local custom in multiple ways, not just to distribute property during decision-making about inheritance, but to assign responsibility for the care of the sick or of children and to distribute the funeral debts. In contemporary Ghana, the period of inheritance decision- making is a time when profound ethical ambiguities in kinship and social relations become apparent. To understand how inheritance is changing, I argue that analysts need to discard assumptions that matrilineal kinship and marriage is inherently harmful to women as well as assumptions about the progressive nature of social change. Instead, I argue that inheritance is an emergent process that combines both general cultural knowledge and the particular knowledge of a deceased individual’s life and relationships to produce decisions that assign responsibility and reform relations that have been disrupted by death. -

Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276087553 Truncation of SOme Akan Personal Names Article in Gema Online Journal of Language Studies · February 2015 DOI: 10.17576/GEMA-2015-1501-09 CITATION READS 1 180 1 author: Kwasi Adomako University of Education, Winneba 8 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Akan loanwords in Ga-Dangme sub-family View project All content following this page was uploaded by Kwasi Adomako on 31 May 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 143 Volume 15(1), February 2015 Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names Kwasi Adomako [email protected] University of Education, Winneba, Ghana ABSTRACT This paper examines some morphophonological processes in Akan personal names with focus on the former process. The morphological processes of truncation of some indigenous personal names identified among the Akan (Asante) ethnic group of Ghana are discussed. The paper critically looks at some of these postlexical morpheme boundary processes in some Akan personal names realized in the truncated form when two personal names interact. In naming a child in a typical Akan, specifically in Asante‟s custom, a family name is given to the child in addition to his/her „God-given‟ name or day-name. We observe truncation and some phonological processes such as vowel harmony, compensatory lengthening, etc. at the morpheme boundaries in casual speech context. These morphophonological processes would be analyzed within the Optimality Theory framework where it would be claimed that there is templatic constraint that demands that the base surname minimally surfaces as disyllable irrespective of the syllable size of the base surname. -

Index Number Name 101001 Agbodza Thomas Kwashie

DOMESTIC NOVDEC 2016 RESULTS INDEX NUMBER NAME 101001 AGBODZA THOMAS KWASHIE 111021 AMEXO GRANT FRANCIS YAW 301040 MOHAMMED ALHASSAN 201002 ABDEEN HASSAN 401001 ABDUL MAJEED ABDUL SOMED 101002 ABDUL RAHAMAN AHMED 101003 ABDUL RAZAK KASSUM 401002 ABDULAI ADAM MARSHAL 111001 ABEKAH JOSHUA 111002 ABOAGYE CHRISTOPHER 301001 ABOAGYE BENARD 101004 ABOAGYE OSBORN DUODU 111003 ABOAGYE PETER 101005 ABOAGYE WILLIAM 201003 ABU SADIQUE 201004 ABUBAKARI HANIF 101006 ABUGRE NATHANIEL ATINGA 401003 ABUKARI ALHASSAN 301002 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN 101007 ACHIANGBON KWABLA 201005 ACKAH PADMORE 301003 ACKAH SAMUEL 101008 ACQUAH BENJAMIN 111004 ACQUAH DICKSON 201006 ACQUETE ASAREWI PAUL 401004 ADAM ABDUL HANAN 201007 ADAMS KOFI 401005 ADAPAH ISAAC KABILLAH 301004 ADDAE ALEXANDER 101010 ADDAE DOUGLAS 101011 ADDO FRANCIS SACKITEY 111005 ADDO KINGSLEY FIANKO 101012 ADDO OBED 201008 ADJEI DAVID 201009 ADJEI FRANCIS 201097 ADJEI JOSEPH 101013 ADJOMAH JOSEPH 101014 ADOARI AWUMBE EUGENE 101015 ADOMAKO DANIEL 111006 ADU KINGSLEY ASIEDU 201011 ADU ERNEST 201012 ADU SAMUEL 101017 ADUKPO DIVINE 111007 ADZAGBA GODKNOWS 101018 AFADEMOR JOSEPH YAW 101019 AFERI SIAW STEPHEN 101214 AFUM EDWARD 111008 AGBANATOR FUTURE 101021 AGBAVOR SIMON 111009 AGBELI JOSEPH KOMLA 101022 AGBEMADE SIMON 111011 AGBODEKA GODSWAY 111012 AGBODZA CHARLES TAWIAH 101026 AGBODZA SAMUEL 301005 AGBOSHIE DAVID 101027 AGORKOR PROSPER 401006 AGURI MAMUDU 101028 AGYAKWAH JOSEPH OFOSU 201014 AGYAPONG BOAME GABRIEL 201015 AGYAPONG FRANK 111013 AGYEI ERIC ANOKYE 201016 AGYEI OLIVER 111014 AGYEMANG EMMANUEL KOJO -

Stamping History: Stories of Social Change in Ghana's Adinkra Cloth

Stamping History: Stories of Social Change in Ghana’s Adinkra Cloth by Allison Joan Martino A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Raymond A. Silverman, Chair Professor Kelly M. Askew Assistant Professor Nachiket Chanchani Professor Emeritus Elisha P. Renne Allison Joan Martino [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-1252-1378 © Allison Joan Martino 2018 DEDICATION To my parents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the summer of 2013, I was studying photography and contemporary art in Accra, Ghana’s capital. A conversation during that trip with Professor Kwesi Yankah changed the course of my research. He suggested a potential research project on adinkra. With adinkra everywhere in Ghana today, research possibilities seemed endless. Adinkra appealed to me from my interest in studying Akan visual and verbal arts, a research area nurtured during an ethnopoetics course that Professor Yankah taught as a visiting scholar at Michigan in 2011. That conversation led to this project. Soon after that meeting with Professor Yankah, I took an exploratory research trip to Kumasi. Professor Gilbert Amegatcher, who has a wealth of knowledge about Akan arts and culture, traveled with me. He paved the way for this dissertation, making key introductions to adinkra cloth makers who I continued to work with during subsequent visits, especially the Boadum and Boakye families. My sincerest thanks are due to Professors Yankah and Amegatcher for generating that initial spark and continuing to support my work. Words cannot express my gratitude to the extended members of the Boakye and Boadum families – especially Kusi Boadum, Gabriel Boakye, David Boamah, and Paul Nyaamah – in addition to all of the other cloth makers I met. -

Undergraduate and Graduate Admission List

UNDERGRADUATE AND GRADUATE ADMISSION LIST 2020/2021 @ FEBRURAY 4 2021 Last Name First Name Middle Name AKIDEI TIMIPRE TORWODZOR STEPHEN AMEKPLENU FOSTER ALHASSAN RUKAYATU LAMPTEY ANTOINETTE Akroway Nana Esi QUARSHIE BERNICE Nazir Bawa ASANTE CHRISTANTIA AKUA ASANTEWAA AKUSSAH HERBERT ELORM ABUTIATE WILSON SAMUEL KWOFIE MAAME ETURBA AMPONSAH ELIZABETH BONDZE SOMPA EWOOL RUTH EFFISIMAH MENSAH CLAUDIA NAA DZAMAH ASANTE GERALD KWABENA MUKHTAR HUSSAINA SHEHU AJIBOYE SUKURAT TADE OTU REBECCA AFIA ADU LARSEY MABEL ADDO BENJAMIN ARMAH OAKLEY GODSON Archampong Rein Ellis Nii Akushey Asare Aboateh Michael GLOVER-ADDY CHRISTABEL KORKOR OKUNTADE FAVOUR OWUSU ROSEMARY ASIEDUA OWUSU SETH KWARTENG OKU JEREMIAH NII ANNAN HOENYEKOR EMMANUEL QWESI AMPADU ALEXANDER OSEI-ABOAGYE FORSTER DANIEL ANTWI SAMPONG GRACE YEBOAH ISSAH RASIATU Mohammed Abdul-Rashid WELLINGTON GODFRED SOLOMON ODARTEI NYARKO SANDRA ADJEI Ankude Rubby Yawa OBILOR MOSES OZIOMA OTOO SHERILINE LYNZIL QUAINOO ABENA PRISCILLA FIBIRI MOHAMMED BEN ABDULAI HAWA AWUNI ISAAC ASHIABI STEPHEN KOBBY ESSEL JOSEPH AHMED ZAROUK MOHAMMED MANSUR IBRAHIM AISHA OKORNOE KELVINA KORKOR ASANTE RICHARD OPATA ANDREWS KWABLAH OBENG-OWUSU FRANCIS OSEI-BONSU FRANK AZAMESU BESAH NKRUMAH ISAAC ABREFI-DSEI YOLANDER NANA AKUA ANUM CONFIDENCE GYAWU TIRZAH-JOY NANA AMA EDJIRY GRACE MAAME EFUA ADU-BOAKYE ALBERT KENDRICK Getor Josephine Elorm AGYEIWAA GLADYS SENIOR ASAMANI ROSEMOND HUDSON OJE KWOFIE PRINCESS JOAN ANTWI SARAPHINA ALABI BLESSING TOFUNMI Achina Melina Owusua NYARKO EZEKIEL ASENSO SAMUEL LOTSU URIEL NUTIFAFA -

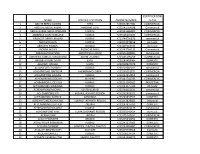

Name Specific Location Phone Number Certification Class

CERTIFICATION NAME SPECIFIC LOCATION PHONE NUMBER CLASS 1 ABAYIE BERKO AKWASI TEPA +233542854981 COMMERCIAL 2 ABDULAI ABDUL-RAZAK MABANG TEPA +233242764598 Commercial 3 ABDUL-KARIM ABDUL RAHMAN KUMASI +233243286809 COMMERCIAL 4 ABEBRESE DJAN ROWLAND KUMASI +233506264844 COMMERCIAL 5 ABOAGYE DANIEL AKWASI KUMASI +233244756870 commercial 6 ABOAGYE ELVIS KUMASI +233242978816 domestic 7 ABOAGYE KWAME BEKWAI +233207163334 domestic 8 ABORAH MOSES BUOHO KUMASI +233247764133 Commercial 9 ABRAHAM BOATENG AKROPONG KUMASI +233246188985 commercial 10 ABROKWA SAMUEL KORANTENG ADUM , KUMASI +233246590209 COMMERCIAL 11 ABUGRI AYAGRI DAVID EJISU +233249458064 DOMESTIC 12 ABUKARI INUSAH EJURA +233200937079 DOMESTIC 13 ACCOMFORD RICHARD KUMASI +233201682011 commercial 14 ACHEAMPONG BAFFOUR AHENEMAKOKOBEN +233248253831 COMMERCIAL 15 ACHEAMPONG AKWASI KUMASI +233242954852 commercial 16 ACHEAMPONG GIDEON MAAKRO +233241744743 COMMERCIAL 17 ACHEAMPONG JOE ELLIS KUMASI +233244560405 INDUSTRIAL 18 ACHEAMPONG KWABENA KUMASI +233243375366 domestic 19 ACHEAMPONG MICHAEL ASAFO-KUMASI +233244102431 commercial 20 ACHEAMPONG NTI KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION +233262428325 commercial 21 ACHEAMPONG PATRICK KONONGO +233249833553 DOMESTIC 22 ACHEAMPONG RICHMOND KUMASI ASHANTI REGION +233243828683 Industrial 23 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN OBUASI +233247937033 DOMESTIC 24 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM KUMASI +233203321176 commercial 25 ACHEAMPONG YAW KUMASI,ASHANTI REGION +233265042424 domestic 26 ACKAH JOHN OBUASI +233275247651 COMMERCIAL 27 ACKAH PADMORE BEKWAI +233245340252 DOMESTIC 28 ACKAH PHILIP -

Asante Traditional Leadership and the Process

ASANTE TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROCESS OF EDUCATIONAL CHANGE A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY OWUSU-KWARTENG August 2005 © 2005 NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY OWUSU-KWARTENG All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled ASANTE TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROCESS OF EDUCATIONAL CHANGE By NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY OWUSU-KWARTENG has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and the College of Education by William Stephen Howard Professor of Telecommunication James Heap Dean, the College of Education OWUSU-KWARTENG, NANA KWAKU WIAFE BROBBEY. Ph.D. August 2005 Educational Studies ASANTE TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROCESS OF EDUCATIONAL CHANGE (222 pp) Director of Dissertation: William Stephen Howard, Ph.D. Abstract This study lies at the intersection of contemporary research on leadership and concerns for the performance of recent African leaders and theme of participation. It utilizes qualitative approaches to examine the issue of leadership and stakeholder participation in the role of Asante traditional leadership and the process of educational change in Ghana during the last quarter of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty- first centuries and the representations that such participation holds for the rest of the country and Africa in the quest for relevant education systems, leadership functions and expectations of stakeholders. The call of the Asantehene (King of Asante), Otumfuo Osei Tutu II at his installation that improved and quality formal education should be a criterion of assessment for his reign; the subsequent establishment of the Otumfuo Education Fund and Offinsoman Education Trust Fund provided the background to formulate the study. -

Kente Cloth Weaving Among the Asante in Ghana a West African Example of Gender and Role Change Resistance

University of Al berta Kente Cloth Weaving among the Asante in Ghana A West African Example of Gender and Role Change Resistance Mari Elizabeth Bergen O A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Textiles and Clothing Department of Human Ecology Edmonton, Alberta Fall 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*m ofcarda du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services senrices bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 ûtrawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire' prêter, distncbuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantieIs may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Kente doth weaving on the namw4p West Afn'can loom is traditionally a male role among the Asante in Ghana. 1 conducted forma1 and informal intewiews with residents of al1 age groups, in Bonwire, to soli& opinion on why or why not women should weave in the village. -

Editor's Introduction

Capturing Students’ Target Language Exposure Collaboratively, on Video – The Akan (Twi) Example Seth Antwi Ofori University of Wisconsin – Madison Abstract: The video project at the center of this paper is one of the strategies the author has been utilizing in teaching Akan as a foreign language aimed at reinforcing aspects of Akan covered in a given semester, specifically as students transition through different levels of language instruction and acquisition or go home on vacation. The significance of this project lies in the fact that it promotes language documenta- tion and material development in less-documented languages, and also, in the fact that it gives foreign language learners the opportunity to reinforce their target language exposure on vacation, or as they transition through the different levels of study, because each student gets a copy of the video to watch with their communities outside of the classroom. 1. Introduction The non-availability of videos for teaching Akan as a second language, coupled with students’ inability to retain target language materials, largely as a result of a long school vacation during which they have no access to their new language, are problems that led to this idea of requiring and organizing students each semester to cap- ture much of their language exposure on video. The video at the cen- ter of this article is worth sharing because, while there have been countless articles, dissertations (and even books) on the various me- thods of teaching a foreign language through video (Morris 2000, Steele and Johnson 2000, Rhodes and Pufahl 2004), there have been virtually none on students of less commonly taught, funded, and do- cumented languages working together each semester to document their target language exposure through video. -

THE ARTS of the KOFI-OO-KOFI CULT Owusu-Boakye, Michael A

THE ARTS OF THE KOFI-OO-KOFI CULT Owusu-Boakye, Michael A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AFRICAN ART AND CULTURE Faculty of Art College of Art and Social Sciences July, 2012 Department of General Arts Studies DECLARATION 1 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the MA African Art and Culture degree and that to the best of my knowledge, it contain no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the university, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Owusu-Boakye, Micheal ID No. 20068573………………… ….……………… Signature Date (Candidate) Certified by Dr. Eric Appau Asante ….…… …………. …………………. Signature Date (Supervisor) Certified by Nana Afua Opuku Asare (Miss) …..……………… …………………. Signature Date (Head of Department) ABSTRACT 2 This thesis identifies the various forms of art used in the Kofi-OO-Kofi Religious cult, been operated by Nana KwakuBonsam. How these arts are used and their importance to the cult has been studied. In unveiling this, the qualitative research method was used to collect data from a homogeneous population using purposive sampling method. Critical observation of the cult processes, questioning and interviewing some of the high ranking officials who are prime users and performers of the arts of this cult, took place. Kofi-OO-Kofi’s cult has resulted from a dissenting view by the priest. Dissenting views results from his perceived spiritual being called Kofi-OO-Kofi who has bestowed powers on him that enables him achieve his targets and aims.