CHAPTER IX ; SOCIAL LIFE in Kaha Rashtra IK I) the Village Unit, Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

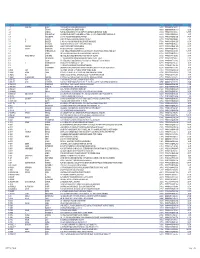

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD and SATI One Unavoidable and Important

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD AND SATI One unavoidable and important consequence of child-inan iages and the practice of polygamy w as a \ iin’s premature widowhood. During the period under study, there was not a single house that did not had a /vidow. Pause, one of the noblemen, had at one time 57 widows (Bodhya which meant widows whose heads A’ere tonsured) in the household A widow's life became a cruel curse, the moment her husband died. Till her husband was alive, she was espected and if she had sons, she was revered for hei' motherhood. Although the deatli of tiie husband, was not ler fault, she was considered inauspicious, repellent, a creature to be avoided at every nook and comer. Most of he time, she was a child-widow, and therefore, unable to understand the implications of her widowhood. Nana hadnavis niiirried 9 wives for a inyle heir, he had none. Wlien he died, two wives survived him. One died 14 Jays after Nana’s death. The other, Jiubai was very beautiful and only 9 years old. She died at the age of 66 r'ears in 1775 A.D. Peshwa Nanasaheb man'ied Radhabai, daugliter of Savkar Wakhare, 6 months before he died, Radhabai vas 9 years old and many criticised Nanasaheb for being mentally derailed when he man ied Radhabai. Whatever lie reasons for this marriage, he was sui-vived by 2 widows In 1800 A.D., Sardai' Parshurarnbhau Patwardlian, one of the Peshwa generals, had a daughter , whose Msband died within few months of her marriage. -

Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Baijayanti Roy Goethe University, Frankfurt Am Main, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 22 Issue 3 Special Issue: 2018 International Conference Article 9 on Religion and Film, Toronto 12-14-2018 Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Baijayanti Roy Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, [email protected] Recommended Citation Roy, Baijayanti (2018) "Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 22 : Iss. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol22/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Abstract This paper examines the tropes through which the Hindi (Bollywood) historical films Bajirao Mastani (2015) and Padmaavat (2018) create idealised pasts on screen that speak to Hindu nationalist politics of present-day India. Bajirao Mastani is based on a popular tale of love, between Bajirao I (1700-1740), a powerful Brahmin general, and Mastani, daughter of a Hindu king and his Iranian mistress. The er lationship was socially disapproved because of Mastani`s mixed parentage. The film distorts India`s pluralistic heritage by idealising Bajirao as an embodiment of Hindu nationalism and portraying Islam as inimical to Hinduism. Padmaavat is a film about a legendary (Hindu) Rajput queen coveted by the Muslim emperor Alauddin Khilji (ruled from 1296-1316). -

THE SWAMI at DHAYAD3HI. the Chhatrapati the Peshwa Iii) The

156 CHAPTER lY : THE SWAMI AT DHAYAD3HI. i) The Chhatrapati ii) The Peshwa iii) The Nobility iv) The Dependents. V) His iiind* c: n .. ^ i CHAPTER IV. THE SWAia AT DHAVADSHI, i) The Chhatrapatl* The eighteenth century Maratha society was religious minded and superstitious. Ilie family of the Chhatrapati was n6 exception to this rule. The grandmother of the great Shivaji, it is said, had vowed to one pir named Sharifji.^ Shivaji paid homage to the Mounibawa of - 2 Patgaon and Baba Yakut of Kasheli. Sambhaji the father of Shahu respected Ramdas. Shahu himself revered Sadhus and entertained them with due hospitality. It is said that Shahu»s concubine Viroobai was dearer to him than his two (^eens Sakwarbai and Sagimabai. Viroobai controlled all Shahu*s household matters. It is 1h<xt said/it was Viroobai who first of all came in contact with the Swami some time in 1715 when she had been to the Konkan for bathing in the sea and when she paid a visit to Brahmendra Swami.^ The contact gradually grew into an intimacy. As a result the Sv/ami secured the villages - 1. SMR Purvardha p . H O 2. R.III 273. 3. HJlDH-1 p. 124. 158 Dhavadshi, Virmade and Anewadi in 1721 from Chhatrapati dhahu. Prince Fatesing»s marriage took place in 1719. life do not find the name of the Swami in the list of the invitees,^ which shows that the Swami had not yet become very familiar to the King, After the raid of Siddi Sad on Parshurajs the Swami finally decided to leave Konkan for good. -

MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL of EXAMINATIONS, PUNE PRINT DATE 16/10/2016 NATIONAL MEANS CUM MERIT SCHOLARSHIP SCHEME EXAM 2016-17 ( STD - 8 Th )

MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL OF EXAMINATIONS, PUNE PRINT DATE 16/10/2016 NATIONAL MEANS CUM MERIT SCHOLARSHIP SCHEME EXAM 2016-17 ( STD - 8 th ) N - FORM GENERATED FROM FINAL PROCESSED DATA EXAM DATE : 20-NOV.-2016 Page : 1 of 222 DISTRICT : 11 - MUMBAI SR. SCHOOL SCHOOL SCHOOL NAME STUDENT NO. CODE TALUKA COUNT CENTRE : 1101 FELLOWSHIP HIGH SCHOOL, AUGUST KRANTI MAIDAN, GRANT ROAD, MUMBAI UDISE : 27230100974, TALUKA ALLOCATED : 1 1141001COLABA SAU.USHADEVI P. WAGHE H. SCHOOL, COLABA MUMBAI 6 6 2 1142023DONGRI CUMMO JAFFAR SULEMAN GIRLS HIGH SCH. MUM - 3 3 3 1143002MUMBADEVI SEBASTIAN GOAN HIGH SCHOOL, ST. FRANCIS XAVIER'S MUM-2 11 4 1143016MUMBADEVI S. L. AND S. S. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL MUMBAI -2 14 5 1144015GIRGAON FELLOWSHIP SCHOOL GRANT RD AUGUST KRANTI MARG MUMBAI - 35 1 6 1144019GIRGAON ST. COLUMBA SCHOOL GAMDEVI MUMBAI - 7 8 7 1144026GIRGAON CHIKITSAK SAMUHA SHIROLKAR HIGH SCHOOL GIRGAON MUMBAI - 4 27 8 1145017BYCULLA ANJUMAN KHAIRUL ISLAM URDU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 2ND GHELABAI ST 12 CENTRE TOTAL 82 CENTRE : 1102 R. M. BHATTA HIGH SCHOOL, PAREL UDISE : 27230200215, TALUKA ALLOCATED : 1 1144050GIRGAON SUNDATTA HIGH SCHOOL NEW CHIKKALWADI SLEAT RD MUMBAI - 7 5 2 1145003BYCULLA SIR ELLAY KADOORI HIGH SCHOOL MAZGAON MUM - 10 8 3 1146004PAREL BENGALI EDUCATION SOCIETY HIGH SCHOOL, NAIGAON, MUMBAI- 14 5 4 1146006PAREL NAV BHARAT VIDYALAYA, PAREL M, MUMBAI- 12 3 5 1146015PAREL R. M. BHATT HIGH SCHOOL, PAREL, MUMBAI- 12 7 6 1146021PAREL ABHUDAYA EDU. ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL, KALACHOWKI, MUMBAI-33 7 7 1146022PAREL AHILYA VIDYA MANDIR, KALACHOWKI, MUMBAI- 33 31 8 1146023PAREL SHIVAJI VIDYALAYA, - KALACHOWKI, MUMBAI- 33 8 9 1146025PAREL S. -

Maharashtra State Legislative Council Electoral Roll-2017 Nashik Division Teacher Constituency DISTRICT :-Jalgaon PART NO -: 11 TALUKA :-AMALNER Suppliment-1 List

Maharashtra State Legislative Council Electoral Roll-2017 Nashik Division Teacher Constituency DISTRICT :-Jalgaon PART NO -: 11 TALUKA :-AMALNER Suppliment-1 List Name Of Elector Name if Father /mother Address Gende Sr No Schoo/College Name Age EPIC No Elector Photo 807 AGRAWAL JAGDISH AGRAWAL CHHOTALAL PRATAP MIL COMPOUND PRATAP COLLEGE AMALNER 54 M 0 808 AGRAWAL PRAKASH AGRAWAL BANSILAL KACHERI ROAD PRATAP COLLEGE AMALNER 56 M 0 809 AGRAWAL AGRAWAL KANHAIYALAL MAHARANA PRATAP MARG NEAR PRATAP COLLEGE AMALNER 58 M 0 RAJENDRAKUMAR PNB 810 AHIRRAO VASANT AHIRRAO CHUDAMAN RAM NAGAR BEHIND MARKET PRATAP COLLEGE AMALNER 59 M 0 811 AHUJA HEMENDRA AHUJA VASUDEV SINDHI COLONY AMALNER PRATAP HIGH SCHOOL AMALNER 36 M DST1540244 812 AMODEKAR PRACHI AMODEKAR PRASAD GURUPRASAD NEAR SAI MANDIR N T MUNDADA MADHYA VIDYALAY 43 F DST1654227 AMALNER AMALNER 813 BADGUJAR MACCHINDRA BADGUJAR RAJARAM REU NAGAR DHEKU ROAD PANDIT NEHARU SAH SHETI VIDYA 55 M DST2457588 NAVALNAGAR DHULE 814 BADGUJAR VIVEK BADGUJAR CHANDULAL JIVAN JYOTI COLONY PRATAP COLLEGE AMALNER 30 M 0 815 BAGALE MANIK BAGALE MADHAV AT POST NAGAON KISAN ARTS & COMMERCE 42 M MT/16/092/0318188 SCIENCE COLLEGE PAROLA 1 Maharashtra State Legislative Council Electoral Roll-2017 Nashik Division Teacher Constituency DISTRICT :-Jalgaon PART NO -: 11 TALUKA :-AMALNER Suppliment-1 List Name Of Elector Name if Father /mother Address Gende Sr No Schoo/College Name Age EPIC No Elector Photo 816 BAGALE MAYA BAGALE DAGADU AT POST SHIRUD V Z PATIL HIGH SCHOOL SHIRUD 31 F UVO3310562 817 BAVISKAR JITENDRA BAVISKAR -

6. Shinde Santosh

RESUME Mr . Shinde Santosh Jagannath C/O -Tanaji Nivangune,Shrikrupa Nivas,Nivrutti Nagar, Charwad Vasti, Vadgaon(BK), Pune - 411041 . Mobile No: - 9975999996, 9970135893 Email-Id: - [email protected] [email protected] CAREER OBJECTIVE: In the Field of Teaching, I believe in hard work and implementing my duties with dedication and determination. I would like to work in well known organization and take up a job, which gives me an opportunity to prove my potential. WORK EXPERIENCE : ( 4.6 Years) Sr. Designation From To Name of College/Institution Responsibilities No. Asst.Teacher 01/06/2007 31/12/2007 Ahilyabai Holkar Shikshan Teaching 1. Sanstha,Anthurne. Sinhgad Technical Education Society's,Smt.Kashibai Navale Teaching 2. Lecturer 01/01/2010 19/07/2011 College of Education (D.T.Ed), (B.Ed),Kusgaon (BK),Lonavala, Tal-Maval,Dist-Pune. STES,SSPM,Sant Dyaneshvar Asst. Prof. 20/07/2011 30/04/2012 Shikshanshatra Mahavidyalaya Teaching 3. (B.Ed),Kondhapuri, Tal-Shirur,Dist-Pune. Kasturi Shikshan Sanstha's Asst. Prof. 01/07/2012 14/07/2013 College of Education Teaching 4. (B.Ed,M.Ed),Shikrapur, Tal-Shirur,Dist-Pune,412208. Sinhgad Technical Education Asst. Prof. 15/07/2013 Continue… Society's,Smt.Kashibai Navale Teaching 5. College of Education (B.Ed), Kusgaon (BK),Lonavala, Tal-Maval,Dist-Pune EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS: M.A (Eng.), M.Ed, SET (Education), DSM, M.Phil Sr. Exam College Board/ Year of Percentage Grade No. University Passing Shri Chhatrapati March 1. S.S.C. High School, Pune Board 1999 63.73 % 1st Class Anthurne H.S.C. Shri Vardhaman Pune Board Feb. -

College Name a Mirza Vjnt Sec & Hr Sec Ashram Shala A

COLLEGE NAME A MIRZA VJNT SEC & HR SEC ASHRAM SHALA A.GULABRAOJI GAWANDE JR COLLEGE BORGAON ABASAHEB PARWEKAR JUNIOR COLLEGE ABDUL RAJIK URDU HIGH SEC SCHOOL ABDUL RASHID MEMORI- AL,URDU SEC.& HIGH ABHINAV JR COLLEGE JANUNA,TQ-NANDGAON ABHYANKAR GIRLS JUNIOR COLLEGE ADARSH ARTS & COMM JUNIOR COLLEGE ADARSH ARTS HIGH SEC SCHOOL,SHIDOLA ADARSH HIGH SEC. SCHOOL,UMALI ADARSH JR COLLEGE AKOT ROAD ADARSH JR COLLEGE TIWRI ADARSH JUNIOR COLLEGE ,MUKUTBAN ADARSH KANYA JR COLLEGE MURTIZAPUR ADARSH SEC & HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL ADARSH SEC & HR SEC SCH. DHANORA GURAV ADARSHA ARTS SCI & BIRLA COMM COLLEGE ADARSHA JR COLLEGE SINGAON JAHANGIR ADARSHA JR SCI COLL CHIKHALI ADARSHA JR SCIENCE COLLEGE,KAPSHI RD ADARSHA KALA HIGH SEC.SCHOOL,MARDI ADARSHA MADHYA & UCHCHA MADHYA VIDYA ADARSHA SEC. & HIGH SEC. SCHOOL ,WANI ADIVASI HIGH SEC SCHOOL,SALONA ADIVASI HIGHER SEC SCHOOL TUNAKI BK. ADV SHANKARRAO RATHOD HR SEC SCHOOL AHILYABAI HOLKAR HR SEC GIRLS SCHOOL AIDED JUNIOR COLLEGE AJGAR HUSAIN URDU JR COLLEGE KHOLAPUR AJHAR FARKHANDA URDU JR COLLEGE,GHODEGAO AJIT DADA PAWAR JR COL RANI AMRAVATI AKOLA ARTS COM & SCI NEW JUNIOR COLLEGE AKOT JUNIOR COLLEGE KRISHI, AKOT ALI ALLANA URDU SCI. HIGH SEC.SCHOOL, ALKHAIR URDU JR COLL TALEGAON MOHNA ALPALAH SHAMIM AZAD URDU H.SEC SCHOOL AMAR JUNIOR COLLEGE AMDAPUR AMARSINH JUNIOR COLLEGE AMBIKA HR SEC SCHOOL MANGLADEVI TQ NER AMINA AJIJ URDU SCI. HIGH SEC.SCHOOL, AMINA URDU HIGH SECH SCHOOL,PINJAR AMOLAKCHAND MAHA- VIDYALAYA ANAND JUNIOR COLLEGE WALGAON ANANTRAO SARAF JR. COLLEGE SHELAPUR BK ANGLO HINDI JUNIOR COLLEGE ANJUMAN ANWAL ESLAM JR COLL OF SCIENCE ANJUMAN JUNIOR COLLEGE ANJUMAN URDU HIGH & SCI. -

2020-2021 (As on 31 July, 2020)

NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL (NAAC) Universities accredited by NAAC having valid accreditations during the period 01.07.2020 to 30.06.2021 ACCREDITATION VALID S. NO. STATE NAME UPTO 1 Andhra Pradesh Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur – 522510 (Third Cycle) 12/15/2021 2 Andhra Pradesh Andhra University,Visakhapatnam–530003 (Third Cycle) 2/18/2023 Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management [GITAM] (Deemed-to-be-University u/s 3 of the UGC Act 1956), 3 Andhra Pradesh 3/27/2022 Rushikonda, Visakhapatnam – 530045 (Second Cycle) 4 Andhra Pradesh Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University Kakinada, East Godavari, Kakinada – 533003 (First Cycle) 5/1/2022 Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha (Deemed-to-be-University u/s 3 of the UGC Act 1956), Tirupati – 517507 (Second 5 Andhra Pradesh 11/14/2020 Cycle) 6 Andhra Pradesh Sri Krishnadevaraya University Anantapur – 515003 (Third Cycle) 5/24/2021 7 Andhra Pradesh Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam, Tirupati – 517502 (Third Cycle) 9/15/2021 8 Andhra Pradesh Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati, Chittoor - 517502 (Third Cycle) 6/8/2022 9 Andhra Pradesh Vignan's Foundation for Science Technology and Research Vadlamudi (First Cycle) 11/15/2020 10 Andhra Pradesh Yogi Vemana University Kadapa (Cuddapah) – 516003 (First Cycle) 1/18/2021 11 Andhra Pradesh Dravidian University ,Srinivasavanam, Kuppam,Chittoor - 517426 (First Cycle) 9/25/2023 Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation (Deemed-to-be-University u/s 3 of the UGC Act 1956),Green Fields, 12 Andhra Pradesh 11/1/2023 Vaddeswaram,Guntur -

CHAPTER 3 CHILD BRIDE and WIFE for a Hinju, Maniage Is A

CHAPTER 3 CHILD BRIDE AND WIFE For a HinJu, maniage is a Sarriskara or a sacrament. A Hindu marriage is looked upon, as, something which is more of a rehgious dut\’ and less of a physical luxury. A Vedic passage says that a person, who is unmvirried is unholy From the religious point of view he remains incomplete and is not fully eligible to participate in sacraments. This continues to be the view of the society even today; the practice of keeping the bet el nut by one’s side in the absaice of tlie wife is an example of this belief. Marriage according to the Shastras is the holy sacrament and the gift of the daughter, (Kanyadaan) to a suitable person, is a sacred duty put on the father, after the performance of which the father gets great spiritual benefit. Marriage is binding for life because the marriage rite completed by Sapkipadi (walking seven steps together) around the sacred fire and is believed to create a religious tie which once created cannot be dissolved. The object of marriage was procreation of children and proper performance of religious ceremonies. Marriage is not perfonned for mere emotional gratification and is not considered as a mere betrothal. Its context s religious, and it is not a mere socio-legal contract. The bride on the seventh step of the Saptapadi, loses her triginal Goira and acquires the Gotra of the bridegroom and a kinship is created that is not a mere friendship for ileasure. Therefore, a marriage Was regai ded as indissoluble. A marriage does not become invalid on the ground that it is effected during the minority of either the ride v^r the groom. -

The Western India Mission Presbyterian Church In

1935 The Western India Mission O F T H E Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. PART I Minutes of the Executive Committee from October 20,1934 to October 10, 1935 f i i l X PART XI Minutes of the Annual Meeting October 10, 1935 to October 19, 1935 1935 The Western India Mission O F T H E | ■ Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. PART I Minutes of the Executive Committee from October 20, 1934 to October 10, 1935 PART II Minutes of the Annual Meeting October 10, 1935 to October 19, 1935 The Western India Mission O F T H E Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. OFFICERS, COMMITTEES AND REPRESENTATIVES I 9 3 5 'I 9 3 6 President ... Rev. A. L. Wiley, Ph. D. Secretary ... Rev. Horace K. Wright Treasurer ... Rev. H. G. Howard Statistician . Rev James E. Napp, D.D. Executive Committee Rev. Horace K. Wrright, Chairman Rev. F. O. Conser Rev. D. B. Updegraff, D.D. Rev. H. G. Howard Rev. A. L. Wiley, Ph.D. Miss C. Grace Deen *J. L. Goheen, Esq., (until fur- L. Bruce Carruthers, M.D. lough) Rev. W. H. Lyon J. C. Kincaid (succeeds Mr. Goheen) DEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEES Educational Committee: Chairman.—Rev. A. L. Wiley, Ph.D. Ad Interim Committee.—Dr. Wiley, Mrs. H. W. Brown, Messrs. G. V. Moses, G. K. Ohol, and M. C. Gorde. Indian Members.—G. V. Moses, G. B. Ghatge, A. B. Phansophkar, G. K. Ohol, S. S. Samudre, Jaywantibai V. Hazare, Valubai G. Chopade, Miss M. Cornelius, M.