Humanities Research Paper 2019 ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

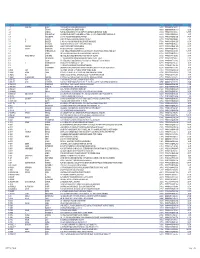

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

India's Missed Opportunity: Bajirao and Chhatrapati

India's Missed Opportunity: Bajirao and Chhatrapati By Gautam Pingle, Published: 25th December 2015 06:00 AM http://www.newindianexpress.com/columns/Indias-Missed-Opportunity-Bajirao-and- Chhatrapati/2015/12/25/article3194499.ece The film Bajirao Mastani has brought attention to a critical phase in Indian history. The record — not so much the film script — is relatively clear and raises important issues that determined the course of governance in India in the 18th century and beyond. First, the scene. The Mughal Empire has been tottering since Shah Jahan’s time, for it had no vision for the country and people and was bankrupt. Shah Jahan and his son Aurangzeb complained they were not able to collect even one-tenth of the agricultural taxes they levied (50 per cent of the crop) on the population. As a result, they were unable to pay their officials. This meant that the Mughal elite had to be endlessly turned over as one set of officials and generals were given the jagirs-in-lieu-of-salaries of their predecessors (whose wealth was seized by the Emperor). The elite became carnivorous, rapacious and rebellious accelerating the dissolution of the state. Yet, the Mughal Empire had enough strength and need to indulge in a land grab and loot policy. Second, the Deccan Sultanates were enormously rich because they had a tolerable taxation system which encouraged local agriculture and commerce. The Sultans ruled a Hindu population through a combined Hindu rural and urban elite and a Muslim armed force. This had established a general ‘peace’ between the Muslim rulers and the Hindu population. -

New Microsoft Office Excel Worksheet.Xlsx

DETAILS OF UNPAID/UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR fy‐2013‐14 AS ON 1ST AUGUST,2017 Prpoposed Amount Date of TransferrTransferr TransferTransfer to Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP Id‐Client Id Account Number Investment Type ed IEPF NITIN JAIN 1003 DLF PHASE‐IV GURGAON HARYANA INDIA HARYANA GURGAON 122001 C12016400‐12016400‐00057150 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 2400.00 15‐SEP‐2021 KAMAL NARAYAN SONI DOOR NO.11‐10‐14, BONDADA VEEDHI, NEAR MAZID, VIZIANAGARAM. ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA KERALA TRIVANDRUM 695010 C12013500‐12013500‐00012773 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 6.00 15‐SEP‐2021 SAPAN NEMA SAPAN NEMA KHARAKUWA SHUJALPUR CITY SHUJALPUR M.P INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560001 C12031600‐12031600‐00126133 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 30.00 15‐SEP‐2021 SRINIVAS H KULKARNI NO: 528/2 BHAGYANAGAR BLOCK‐2,KOPPALA RAICHUR KARNATAKA INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560001 C12032800‐12032800‐00135284 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 3.60 15‐SEP‐2021 RADHEY SHYAM PANDEY S/O RAM NARAYAN PANDEY NASOORUDDINPUR SATHIAON, SADAR TEHSIL AZAMGARH UP INDIA UTTAR PRADESH GORAKHPUR 273001 C13025900‐13025900‐00822209 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 24.00 15‐SEP‐2021 VASUNDHARA SHARMA K.G.TILES FACTORY KE PICHHE CHOPRA KATLA RANI BAZAR BIKANER RAJASTHAN INDIA RAJASTHAN AJMER 305001 C12017701‐12017701‐00148886 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 6.00 15‐SEP‐2021 SANJAY BAJPAI H No.‐ 747 LUCKNOW ROAD HARDOI U.P. INDIA UTTAR PRADESH GORAKHPUR 273001 C12032700‐12032700‐00104476 -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

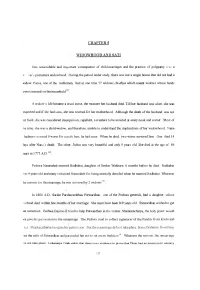

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD and SATI One Unavoidable and Important

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD AND SATI One unavoidable and important consequence of child-inan iages and the practice of polygamy w as a \ iin’s premature widowhood. During the period under study, there was not a single house that did not had a /vidow. Pause, one of the noblemen, had at one time 57 widows (Bodhya which meant widows whose heads A’ere tonsured) in the household A widow's life became a cruel curse, the moment her husband died. Till her husband was alive, she was espected and if she had sons, she was revered for hei' motherhood. Although the deatli of tiie husband, was not ler fault, she was considered inauspicious, repellent, a creature to be avoided at every nook and comer. Most of he time, she was a child-widow, and therefore, unable to understand the implications of her widowhood. Nana hadnavis niiirried 9 wives for a inyle heir, he had none. Wlien he died, two wives survived him. One died 14 Jays after Nana’s death. The other, Jiubai was very beautiful and only 9 years old. She died at the age of 66 r'ears in 1775 A.D. Peshwa Nanasaheb man'ied Radhabai, daugliter of Savkar Wakhare, 6 months before he died, Radhabai vas 9 years old and many criticised Nanasaheb for being mentally derailed when he man ied Radhabai. Whatever lie reasons for this marriage, he was sui-vived by 2 widows In 1800 A.D., Sardai' Parshurarnbhau Patwardlian, one of the Peshwa generals, had a daughter , whose Msband died within few months of her marriage. -

Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018

Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018 Contradictory Perspectives on Freedom and Restriction of Expression in the context of Padmaavat: A Case Study Ms. Ankita Uniyal, Dr. Rajesh Kumar Significance of Media in Strengthening Democracy: An Analytical Study Dr. Harsh Dobhal, Mukesh Chandra Devrari “A Study of Reach, Form and Limitations of Alternative Media Initiatives Practised Through Web Portals” Ms. Geetika Vashishata Employer Branding: A Talent Retention Strategy Using Social Media Dr. Minisha Gupta, Dr. Usha Lenka Online Information Privacy Issues and Implications: A Critical Analysis Ms. Varsha Sisodia, Prof. (Dr.) Vir Bala Aggarwal, Dr. Sushil Rai Online Journalism: A New Paradigm and Challenges Dr. Sushil Rai Pragyaan: Journal of Mass Communication Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018 Patron Dr. Rajendra Kumar Pandey Vice Chancellor IMS Unison University, Dehradun Editor Dr. Sushil Kumar Rai HOD, School of Mass Communication IMS Unison University, Dehradun Associate Editor Mr. Deepak Uniyal Faculty, School of Mass Communication IMS Unison University, Dehradun Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Subhash Dhuliya Former Vice Chancellor Uttarakhand Open University Haldwani, Uttarakhand Prof. Devesh Kishore Professor Emeritus Journalism & Communication Research Makhanlal Chaturvedi Rashtriya Patrakarita Evam Sanchar Vishwavidyalaya Noida Campus, Noida- 201301 Dr. Anil Kumar Upadhyay Professor & HOD Dept. of Jouranalism & Mass Communication MGK Vidhyapith University, Varanasi Dr. Sanjeev Bhanwat Professor & HOD Centre for Mass Communication University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Copyright @ 2015 IMS Unison University, Dehradun. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission. Application for permission for other use of copyright material including permission to reproduce extracts in other published works shall be made to the publisher. -

Bookmyshow Sells Close to 5 Million Tickets for Padmaavat

BookMyShow sells close to 5 million tickets for Padmaavat Expects February to be a great month for movies business with films like Padman, Aiyaari lined up Mumbai, February 5, 2018: BookMyShow, India’s largest online entertainment ticketing platform, said that it has alone sold close to 5 million tickets for Padmaavat since the release of the film on January 26, 2018. The Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh, Shahid Kapoor starrer enjoyed a two week clear run at the box-office, though a few cities were not part of the release. BookMyShow, the category leader in online movie ticketing, contributed over 60% of Padmaavat’s opening weekend collection – a staggering contribution for a blockbuster release – achieving over INR 100 Crore collection on BookMyShow. The Sanjay Leela Bhansali magnum opus sold tickets across 340 cities and towns and was released in Hindi, Tamil and Telugu, in 2D, 3D and IMAX. The film’s first ticket was booked from Jharsuguda in Odisha, while maximum number of tickets for Padmaavat were sold in Mumbai, followed by Delhi, Hyderabad and Bengaluru. Padmaavat, which was clearly the movie of the month for the Indian film industry, contributed to over 35% of the total movie ticket sales on BookMyShow in the month. BookMyShow also rolled out an ad film (BookMyShow TV Ad | Touchy Topic) and a digital film (BookMyShow Video Ad | Padmaavat – Jao Book Now) around the movie which was viewed and shared by millions of movie lovers across the country. Marzdi Kalianiwala, VP- Marketing and Business Intelligence, BookMyShow said, “Padmaavat has definitely given the movies business a great start this year. -

Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Baijayanti Roy Goethe University, Frankfurt Am Main, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 22 Issue 3 Special Issue: 2018 International Conference Article 9 on Religion and Film, Toronto 12-14-2018 Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Baijayanti Roy Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, [email protected] Recommended Citation Roy, Baijayanti (2018) "Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 22 : Iss. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol22/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Abstract This paper examines the tropes through which the Hindi (Bollywood) historical films Bajirao Mastani (2015) and Padmaavat (2018) create idealised pasts on screen that speak to Hindu nationalist politics of present-day India. Bajirao Mastani is based on a popular tale of love, between Bajirao I (1700-1740), a powerful Brahmin general, and Mastani, daughter of a Hindu king and his Iranian mistress. The er lationship was socially disapproved because of Mastani`s mixed parentage. The film distorts India`s pluralistic heritage by idealising Bajirao as an embodiment of Hindu nationalism and portraying Islam as inimical to Hinduism. Padmaavat is a film about a legendary (Hindu) Rajput queen coveted by the Muslim emperor Alauddin Khilji (ruled from 1296-1316). -

Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through the Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857?

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Glimpses of Jhansi's History Jhansi Through The Ages Newalkars of Jhansi What Really Happened in Jhansi in 1857? Attractions in and around Jhansi Jhansi Fort Rani Mahal Ganesh Mandir Mahalakshmi Temple Gangadharrao Chhatri Star Fort Jokhan Bagh St Jude’s Shrine Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery Jhansi Railway Station Orchha I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi is one of the most vibrant cities of Uttar Pradesh today. But the city is also steeped in history. The city of Rani Laxmibai - the brave queen who led her forces against the British in 1857 and the region around it, are dotted with monuments that go back more than 1500 years! While thousands of tourists visit Jhansi each year, many miss the layered past of the city. In fact, few who visit the famous Jhansi Fort each year, even know that it is in its historic Ganesh Mandir that Rani Laxmibai got married. Or that there is also a ‘second’ Fort hidden within the Jhansi cantonment, where the revolt of 1857 first began in the city. G L I M P S E S O F J H A N S I ’ S H I S T O R Y JHANSI THROUGH THE AGES Jhansi, the historic town and major tourist draw in Uttar Pradesh, is known today largely because of its famous 19th-century Queen, Rani Laxmibai, and the fearless role she played during the Revolt of 1857. There are also numerous monuments that dot Jhansi, remnants of the Bundelas and Marathas that ruled here from the 17th to the 19th centuries. -

Actor Rishi Kapoor Dies at 67 After a Long Battle with Cancer

INDIAN01 May, 2020 | Friday | Volume No: 8| Issue No: 62 Pages: 8 CHRONICLE www.indianchronicle.com Published from : Ranga Reddy (Telangana State) 3 99-year-old woman from Telangana donates TS EAMCET 2020 receives over 1.9 lakh Rs 9999 to CM relief fund on her birthday applications, last date is May 5 The Telangana State engineering, agriculture, medicine common entrance test (TS EAMCET) 2020 has re- A 99-year-old woman from Marikal mandal of Narayanpet district in Telangana has donated Rs 9,999 to ceived around 1,92,162 applications till April 29, 2020, said CET convener professor Govardhan in a release. The Chief Minister Relief Fund (CMRF) on her birthday. The woman by the name Seshamma handed over the money convener said that the last date to submit the applications for EAMCET exam will end on May 5. There are also to Marikal tahsildar supporting the government to fight against coronavirus. Tahsildar and other officials appreci- chances of extending the last date in the view of coronavirus lockdown, he added.Meanwhile, the Telangana State ated Seshamma for her kind gesture. Many of the people are coming forward to help the government by donating Council of Higher Education (TSCHE) has decided to“4/30/2020 TS EAMCET 2020 receives over 1.9 lakh applica- money,“4/30/2020 99-year-old woman from Telangana donates Rs 9999 to CM relief fund on her birthday tions, last date is May5Meanwhile, the Telangana State Council of Higher Education (TSCHE) has decided to conduct the TS EAMCET 2020 either in the third or fourth week of June.