Security Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strada Radu Calomfirescu HCL Nr

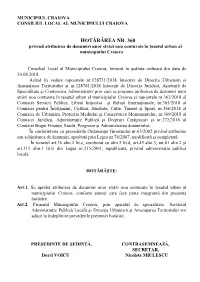

MUNICIPIUL CRAIOVA CONSILIUL LOCAL AL MUNICIPIULUI CRAIOVA HOTĂRÂREA NR. 360 privind atribuirea de denumiri unor străzi nou conturate în țesutul urban al municipiului Craiova Consiliul Local al Municipiului Craiova, întrunit în şedinţa ordinară din data de 30.08.2018. Având în vedere rapoartele nr.128731/2018 întocmit de Direcţia Urbanism şi Amenajarea Teritoriului și nr.128761/2018 întocmit de Direcția Juridică, Asistență de Specialitate și Contencios Administrativ prin care se propune atribuirea de denumiri unor străzi nou conturate în țesutul urban al municipiului Craiova și rapoartele nr.362/2018 al Comisiei Servicii Publice, Liberă Iniţiativă şi Relaţii Internaţionale, nr.365/2018 al Comisiei pentru Învăţământ, Cultură, Sănătate, Culte, Tineret şi Sport, nr.366/2018 al Comisiei de Urbanism, Protecţia Mediului şi Conservarea Monumentelor, nr.369/2018 al Comisiei Juridică, Administraţie Publică şi Drepturi Cetăţeneşti şi nr.372/2018 al Comisiei Buget Finanţe, Studii, Prognoze i Administrarea domeniului; În conformitate cu prevederile Ordonanţei Guvernului nr.63/2002 privind atribuirea sau schimbarea de denumiri, aprobată prin Legea nr.76/2007, modificată i completată; În temeiul art.36 alin.2 lit.c, coroborat cu alin.5 lit.d, art.45 alin.3, art.61 alin.2 şi art.115 alin.1 lit.b din Legea nr.215/2001, republicată, privind administraţia publică locală; HOTĂRĂŞTE: Art.1. Se aprobă atribuirea de denumiri unor străzi nou conturate în țesutul urban al municipiului Craiova, conform anexei care face parte integrantă din prezenta hotărâre. Art.2. Primarul Municipiului Craiova, prin aparatul de specialitate: Serviciul Administraţie Publică Locală şi Direcţia Urbanism şi Amenajarea Teritoriului vor aduce la îndeplinire prevederile prezentei hotărâri. -

124 Warfare Actions of the Large Romanian Military

WARFARE ACTIONS OF THE LARGE ROMANIAN MILITARY UNITS FOR DEFENSE AND EVACUATION OF CRIMEA IN WORLD WAR II Colonel (ret.) professor Benone ANDRONIC, PhD* Abstract: Researching the existing Romanian and foreign bibliography, regarding the circumstances in which combat forces from the Romanian Army will end up carrying out combat actions, together with Wehrmacht troops, for the defense of Crimea and then the evacuation of troops from the Peninsula, in the World War II, the authors highlight some aspects of these operations, which are less known, and which have sometimes given rise to different and even biased approaches. The analysis shows the steps taken by Marshal Ion Antonescu and the Chief of the General Staff of the Romanian Army, General Ilie Șteflea, to determine Hitler to order the evacuation of troops from large units of the Romanian Army in Crimea, as well as the execution thereof. Keywords: Crimea as strategic objective in the Black Sea; coalition war; politico-military decisions; the Soviet offensive; defense of German-Romanian forces; evacuation of troops. Introduction In July 1942, after the total conquest of Crimea by German and Romanian troops, the southern flank of the German-Soviet front would become the center of gravity for military operations. On June 28, 1942, Army Groups B and A began offensive operations with the mission to conquer the Stalingrad and reach the Volga, as well as the subsequent conquest of the Caucasus, to gain access to oil fields, a mandatory condition for the offensive continuation on Soviet territory. In the summer of 1942, the Wehrmacht Army, although advancing in the depths of Russian territory, was stopped at Stalingrad1, because it aimed to conquer both it and the Caucasus at the same time and not in turn, which * corresponding member of the Romanian Scientists Academy, [email protected]. -

A NATO Strategy for Security in the Black Sea Region

Atlantic Council BRENT SCOWCROFT CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL SECURITY ISSUE BRIEF A NATO Strategy for Security in the Black Sea Region SEPTEMBER 2016 STEVEN HORRELL he Black Sea region is a crossroads, an intersection between Europe and the Middle East, from the eastern Balkans to the South Caucasus. Like many such points of intersection, it is often a friction point. This is very much the case in the current Tgeopolitical environment of growing confrontation between Russia and the West. Any friction there will almost certainly involve NATO nations and the Alliance’s interests, with three NATO states on the Black Sea and several NATO partners on the Black Sea and throughout the region. Maintaining a dominant role in the Black Sea region forms an important element of Russian strategy; however, Western policymakers have been deficient in giving strategic attention to the Black Sea region in recent years. That may be changing. In addition to emphasizing collective defense and deterrence, the final communiqué of the NATO Warsaw Summit highlighted the importance of the Black Sea region: “We condemn Russia’s ongoing and wide-ranging military build-up in Crimea, and are concerned by Russia’s efforts and stated plans for further military build-up in the Black Sea region.”1 NATO has the opportunity and responsibility to move forward from the statements of the Warsaw Summit. The Black Sea region needs The Brent Scowcroft Center’s NATO as a steadying influence, and NATO needs to address the Transatlantic Security Alliance’s interests in the region. This issue brief offers the framework Initiative brings together top of a NATO strategy to ensure stability in this critical area; it expands policymakers, government and military officials, business on the communiqué’s objectives for security in that region, posits an leaders, and experts from Europe approach, and recommends actions to improve stability and security in and North America to share the Black Sea region. -

Rim Nr.5-6-7Decembrie 2006.Pmd

SUMAR • 90 de ani de la intrarea României în Primul Război Mondial - Război şi alianţe: august 1916 – ANDREI MIROIU .................................... 1 - Eşichierul politic românesc în faţa unei dileme geopolitice – conf. univ. dr. MARIA GEORGESCU......................................................... 9 - Comandamentul Armatei Române în campania din toamna anului 1916 REVISTA DE ISTORIE PETRE OTU ................................................................................................ 18 MILITAR| - Generali şi ofiţeri basarabeni participanţi la Primul Război Mondial Publica]ia este editat\ de Minis- – maior dr. ANATOL LEŞCU, Republica Moldova ...................................... 27 terul Ap\r\rii, prin Institutul - Octavian Goga: Însemnări din zilele războiului nostru – PETRE OTU ..... 32 pentru Studii Politice de Ap\rare - Probleme teritoriale româneşti în discuţia Marilor Puteri (1914-1918) [i Istorie Militar\, membru al – colonel prof. univ. dr. ION GIURCĂ.......................................................... 43 Consor]iului Academiilor de - Propaganda instituţionalizată a Aliaţilor în Primul Război Mondial Ap\rare [i Institutelor pentru – colonel CĂLIN HENTEA ........................................................................... 48 Studii de Securitate din cadrul - Noua realitate politico-statală în Balcani după Primul Război Mondial Parteneriatului pentru Pace, – colonel (r) ALEXANDRU OŞCA ................................................................ 53 coordonator na]ional al Proiec- tului de Istorie Paralel\> -

Renaşte Marina Militară La Tulcea

GRUPUL MASS-MEDIA AL FORŢELOR NAVALE Redactor - şef : Locotent - comandor ION BURGHIŞAN e-mail:[email protected] MARINA ROMÂNĂ Coperta 4: Dragorul maritim Revistă fondată în 1990, editată de Nicolescu în strâmtoarea Bosfor, Statul Major al Forţelor Navale la BLACKSEA PARTNERSHIP’ 05 Coperta 1: Exerciţiu VERTREP pe fregata Secretar de redacţie: Regele Ferdinand Maior Costel SUSANU (Foto: Cătălin Ovreiu) e-mail:[email protected] Redactor: SUMAR Bogdan DINU ŞTIRI DIN FLOTĂ e-mail:[email protected] N.Ş. Mircea în misiune de reprezentare........ 4 . ADRESA REDACŢIEI: EVENIMENT Hotelul Militar Constanţa Reuniunea B-dul Mamaia Nr.92 comandanţilor Marinelor 0241 - 619539 (redactor - şef) Militare de la Marea 0241 – 615700 int. 172 (redacţia) Neagră .....................5 0241 - 619539 (fax) Fregata Regina Maria a e-mail : [email protected] arborat Pavilionul românesc .................7 Se editează 6 numere pe an, cu apariţie la două luni. INSTRUCŢIE Reînfiinţarea unităţii de NORME DE COLABORARE: vedete blindate la Cititorii pot trimite pe adresa redacţiei Tulcea .....................9 texte şi fotografii care se încadrează în tematica revistei. Manuscrisele nu se COOPERARE înapoiază. Răspunderea juridică pentru REGIONALĂ conţinutul articolelor aparţine în Prezenţă activă la BLACKSEAFOR..........11 exclusivitate autorilor, conform art. 206 CP Festivalul maritim COPYRIGHT: Internaţional Este autorizată orice reproducere cu MARMARIS 2005 ......14 condiţia specificării sursei. ISSN: 1222-9423 PAVILION NATO C-da 4643/2005; B-00342 Ritmul operaţionalizării ...21 Tehnoredactarea şi tiparul: Centrul Tehnic-Editorial al Armatei MONITOR PE B-dul Ion Mihalache nr.124-126, DUNĂRE Bucureşti Marinarii fluviali la examen ..................26 Tel.: 021-2242634 ANIVERSĂRI DTP: Sorin DOBRE 145 de ani de la crearea Marinei Militare a României moderne .............................30 AZIMUT CULTURAL ............................ -

Book-Of-Abstracts-2015.Pdf

AMAN`S BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 8th International Conference State and Society in Europe ISSN 2457-4120 ISSN –L 2457-4120 Editor in chief: Lucian Dindirică Scientific Reviewer: Sorin Liviu Damean Executive Editor: Alexandru Ionicescu Editors: Raluca Sandu Dragoș Manea Lavinia Dumitrescu BOOK OF ABSTRACTS of the 8th International Conference STATE AND SOCIETY IN EUROPE, 25th of October - 5th of November, 2015, Craiova, Romania http://sse.conferences.faaa.ro/book-of-abstracts/ Cuprins: 1. Welcoming address / 5 2. Scientific Committee / 8 3. Board of Directors / 9 4. Conference Program / 10 5. Keynote Speakers / 34 6. About the authors / 45 7. Abstracts / 103 Welcoming adress from Mr. Lucian Dindirică, Manager of “Alexandru and Aristia Aman” County Library – Dolj Ladies and gentlemen, First of all, allow me, as the manager of "Alexandru and Aristia Aman" Dolj County Library, to wish you a warm welcome here, in Craiova, at the library. We open today the 8th edition of the International Conference State and Society in Europe. For almost two weeks, Craiova will be the scene of debates, presentations and interventions of the highest academic level. Aman Library, together with The Faculty of Theology of Craiova, Universitaries House and Art Museum of Craiova, will host the entire event, so I hope you will spend here pleasant and productive moments. In a time of full technological and informational upsurge, we all enjoy the fruits of this unprecedented development. Although it is hard for us to admit, most of the times the technological development generates a perverse, dangerous effect. It is a clear fact that lecture and private reading are on a descending course. -

Military Situation

Security Review Giorgi Surmava Russia-Ukraine, 2021 2021 საავტორო უფლებები დაცულია და ეკუთვნის საქართველოს სტრატეგიისა და საერთაშორისო ურთიერთობების კვლევის ფონდს. წერილობითი ნებართვის გარეშე პუბლიკაციის არც ერთი ნაწილი არ შეიძლება დაიბეჭდოს არანაირი, მათ შორის ელექტრონული ან მექანიკური, ფორმით. გამოცემაში გამოთქმული მოსაზრებები და დასკვნები ეკუთვნის ავტორს/ებს და შეიძლება არ ასახავდეს საქართველოს სტრატეგიისა და საერთაშორისო ურთიერთობების კვლევის ფონდის თვალსაზრისს. © საქართველოს სტრატეგიისა და საერთაშორისო ურთიერთობათა კვლევის ფონდი 2021 After the occupation and annexation of Crimea in 2014, the epicenter of hostilities shifted to eastern Ukraine, specifically to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. The Russian-speaking population was not loyal to Kyiv even before that but the events in Crimea and the Russian assistance invigorated the local separatists who, along with adventurers backed by the regular Russian troops, managed to gain control over parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. The fighting turned out to be quite bloody and long lasting. There were large casualties on both sides, including civilians. Coupled with a high-profile incident of the downing of a passenger plane, it caused a wide international reverberation and world interest in resolving the conflict. The efforts of the leading OSCE countries had led to a certain agreement and the cessation of intense hostilities by September 2014. A quadripartite agreement (Germany, France, Russia, Ukraine) was achieved on the separation of the parties and a ceasefire. The line of contact was divided into sectors and precincts where a group of OSCE military observers began to monitor the “silence” regime. Since then, the intensity and scale of the hostilities have been significantly reduced. However, every now and then the situation would worsen which was followed by a new agreement on a ceasefire and the establishment of a “silence” regime. -

Downloaded from the Rescue Card on Board

#11 Black Sea Rotational Force 15.2 Platinum Lynx 16-1 Exercises at sea 265th Military Police Battalion Complex Cooperation Exercise in the Călimani Mountain tactica magazine S-KARP® FELINE The main features of Feline running shoes are: grip, traction, shock absorption, stability, very light weight and comfort, being recommended, especially for mountain and asphalt runs. They are suitable for the most difficult running races, but also for daily activities or various outdoor activities. The very precise elements incorporated in these models almost make the distances no longer matter, offering an extraordinary comfort. S-KARP footwear combines a series of high- performance technologies, along with attention to detail and a lot of experience, being made to protect your feet and to take you wherever you want. The materials used ensure waterproofness, breathability, wind resistance, durability and great comfort. follow Caracteristici tehnice: Față: Mesh Căptușeală: NU click / tap to follow Talpă: Vibram TN333 / Exmoor Mărimi: Euro 36-47 Greutate: ~259 gr (½ mărime 42) content content content content tacticacontent magazine content tacticacontent magazine content content PG#O6 265th Military Police Battalion PG#16 Black Sea Rotational Force 15.2 - Platinum Lynx 16-1 PG#26 Exercises at sea with NATO partners and allies PG#12 Complex Cooperation Exercise in the Călimani Mountain from Suceava County PG#34 Invictus România - Veterans relay PUBLISHER EDITOR IN CHIEF Tactica Media Marcella Drăgan [email protected] UK: +44 750 660 3365 iSSn 2344 – 2581 MARKETING & SUBSCRIPTIONS RO: +40 745 938 006 iSSn–L 2344 – 2581 [email protected] [email protected] Responsibility for texts and images published lies with the authors. -

Marinamarina

MARINAMARINA www.navy.rowww.navy.ro REVISTA FORŢELOR NAVALE ROMÂNE NUMĂR SPECIAL 160 • NUMĂR SPECIAL de ani de la înfiinţarea Marinei Militare Române Moderne Anul XXIX Nr. 6 (208) 2020 • NUMĂR SPECIAL Ochiul Flotei p 1898, Galaţi. p Portul Constanţa. Hala mecanică la Arsenalul Marinei. Urcarea regelui Carol al II-lea la bordul distrugătorului Regele Ferdinand. u Regele Mihai felicitându-l pe locotenent-comandorul Eugeniu Săvulescu. t Constanţa. Distrugătorul Regele Ferdinand şi cargoul Peleş u 1909, Galaţi. la serbările navale Elevii Şcolii de Artilerie, de la Constanţa. Geniu şi Marină. Marina Română nr. 6 număr special – 2020 BUN CART NAINTE ComandanII MARINEI FORELOR NAVALE ROMNE! – 4 Militare ROMNE – 18 număr special 160 DE ANI DE LA NFIINAREA MARINEI FORELE NAVALE ROMNE, MILITARE ROMNE MODERNE – 5 ARC PESTE TIMP SUMAR FORELE NAVALE ROMNE - ISTORIE, 1860-2020 – 36 ACTUALITATE I PERSPECTIVE – 12 Lansarea la apă a distrugătorului Regele Ferdinand. Plecarea în misiune a puitorului de mine şi plase Viceamiral Constantin Bălescu, nava comandant a grupării NATO, SNMCMG2, ianuarie-iunie 2020. CENTRUL MEDIA Mariana Păvăloiu AL FORŢELOR NAVALE Muzeul Naţional al Marinei Române MARINA ROMÂNĂ Muzeul Academiei Navale „Mircea cel Bătrân” Revistă fondată în 1990, Muzeul Militar Naţional editată de Statul Major al Forţelor Navale Redactor-şef: ADRESA REDACŢIEI: Comandor ing. Mihai EGOROV Str. Ştefăniţă Vodă nr. 4 FotograFII: Tel./Fax: 0241-619.539 Ionuţ FELEA e-mail: [email protected] Cristian VLĂSCEANU Ediţia s-a încheiat în data de 14.10.2020 Administraţia Prezidenţială Incursiune Codruţ BURDUJAN NORME DE COLABOraRE: în istoria şi prezentul Ion BURGHIŞAN Cititorii pot trimite pe adresa redacţiei Forţelor Navale Române. -

Regele-Si-Regina-Marii-Negre-Marian

Căpitan-comandor dr. Marian MOŞNEAGU Biblioteca ZIUA de Constanţa Nf.....m........... REGELE SI> REGINA MĂRII NEGRE File din istoricul distrugătoarelor & (regatelor „REGELE FERDINAND" si „REGINA NARIA" www.ziuaconstanta.ro MUNTENIA Constânla 2005 Căpitan-comandor dr. Marian MOŞNEAGU REGELE SI REGINA NĂRn NEGRE File din Islorlcul disirugăloarelor & iregalelor „REGELE FERDINAND” şl „REGINA HARIA” www.ziuaconstanta.ro Colecţia: Nave militare româneşti Culegere computerizată; Elena Moşneagu, Mihaela Mîrşu, Violeta Brânză, Monica Giuglea Corectură: Irina-Alexandra Moşneagu Foto: Fototeca Muzeului Marinei Române, Valentina Leahu, colecţiile revistei „Marina Română”, dr. ing. Cristian Crăciunoiu, ing. Dan Stroescu Procesare foto: Centrul de Informatică al Forţelor Navale Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României MOŞNEAGU, MARIAN Regele şl regina Mării Negre: file din Istoria distrugătoa relor & fregatelor „Regele Ferdlnand” şl „Regina Marla” / căpitan comandor dr. Marian Moşneagu - Conslan|a : Editura Muntenia, 2005 Bibiiogr. ISBN 973-692-108-5 629.5(499)(091) EDITOR: MUNTENIA I.S.B.N.: 973-692-107-7 Consiliere editorială: 0LEDA* [email protected] TIPĂRIT LA: Tipografia MUNTENIA Constanţa Tel./Fax:'0241-635 521 [email protected] Toate drepturilewww.ziuaconstanta.ro sunt rezervate autorului Regele şi Regina Mării Negre unor pagini glorioase de istorie navală românească şi totodată obligate să CUVÂNT ÎNAINTE menţină spiritul de corp, camaraderia şi standardul înalt de performanţă în îndeplinirea misiunilor specifice, atât în apele naţionale cât şi oriunde Forţele Navale Române au celebrat anul în lume. acesta împlinirea a 145 de ani de la crearea După inspiratul album „Odiseea navei-şcoală „CONSTANŢA", componentei fluviale a Marinei Militare dedicat evocării implicării active a acestei nave, în anii 2001 şi 2003, a statului român modem.