Verdi's Requiem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ERNANI Web.Pdf

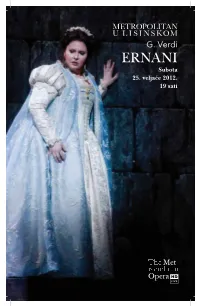

Foto: Metropolitan opera G. Verdi ERNANI Subota, 25. veljae 2012., 19 sati THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Giuseppe Verdi ERNANI Opera u etiri ina Libreto: Francesco Maria Piave prema drami Hernani Victora Hugoa SUBOTA, 25. VELJAČE 2012. POČETAK U 19 SATI. Praizvedba: Teatro La Fenice u Veneciji, 9. ožujka 1844. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 18. studenoga 1871. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 28. siječnja 1903. Premijera ove izvedbe: 18. studenoga 1983. ERNANI Marcello Giordani JAGO Jeremy Galyon DON CARLO, BUDUĆI CARLO V. Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana Dmitrij Hvorostovsky ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo DON RUY GOMEZ DE SILVA DIRIGENT Marco Armiliato Ferruccio Furlanetto REDATELJ I SCENOGRAF ELVIRA Angela Meade Pier Luigi Samaritani GIOVANNA Mary Ann McCormick KOSTIMOGRAF Peter J. Hall DON RICCARDO OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE Gil Wechsler Adam Laurence Herskowitz SCENSKA POSTAVA Peter McClintock Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Radnja se događa u Španjolskoj 1519. godine. Stanka nakon prvoga i drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 22 sata i 50 minuta. Tekst: talijanski. Titlovi: engleski. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: PRVI IN - IL BANDITO (“Mercè, diletti amici… Come rugiada al ODMETNIK cespite… Oh tu che l’ alma adora”). Otac Don Carlosa, u operi Don Carla, Druga slika dogaa se u Elvirinim odajama u budueg Carla V., Filip Lijepi, dao je Silvinu dvorcu. Užasnuta moguim brakom smaknuti vojvodu od Segovije, oduzevši sa Silvom, Elvira eka voljenog Ernanija da mu imovinu i prognavši obitelj. -

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

National-Council-Auditions-Grand-Finals-Concert.Pdf

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Bertrand de Billy National Council Auditions host and guest artist Grand Finals Concert Joyce DiDonato Sunday, April 29, 2018 guest artist 3:00 PM Bryan Hymel Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2017–18 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Bertrand de Billy host and guest artist Joyce DiDonato guest artist Bryan Hymel “Martern aller Arten” from Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Mozart) Emily Misch, Soprano “Tacea la notte placida ... Di tale amor” from Il Trovatore (Verdi) Jessica Faselt, Soprano “Va! laisse couler mes larmes” from Werther (Massenet) Megan Grey, Mezzo-Soprano “Cruda sorte!” from L’Italiana in Algeri (Rossini) Hongni Wu, Mezzo-Soprano “In quali eccessi ... Mi tradì” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Today’s concert is Danielle Beckvermit, Soprano being recorded for “Amour, viens rendre à mon âme” from future broadcast Orphée et Eurydice (Gluck) over many public Ashley Dixon, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Gualtier Maldè! ... Caro nome” from Rigoletto (Verdi) local listings. Madison Leonard, Soprano Sunday, April 29, 2018, 3:00PM “O ma lyre immortelle” from Sapho (Gounod) Gretchen Krupp, Mezzo-Soprano “Sì, ritrovarla io giuro” from La Cenerentola (Rossini) Carlos Enrique Santelli, Tenor Intermission “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Jessica Faselt, Soprano “Down you go” (Controller’s Aria) from Flight (Jonathan Dove) Emily Misch, Soprano “Sein wir wieder gut” from Ariadne auf Naxos (R. Strauss) Megan Grey, Mezzo-Soprano “Wie du warst! Wie du bist!” from Der Rosenkavalier (R. -

The Worlds of Rigoletto: Verdiâ•Žs Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Worlds of Rigoletto Verdi's Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto Mark D. Walters Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE WORLDS OF RIGOLETTO VERDI’S DEVELOPMENT OF THE TITLE ROLE IN RIGOLETTO By MARK D. WALTERS A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Mark D. Walters defended on September 25, 2007. Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise Svetla Slaveva-Griffin Outside Committee Member Stanford Olsen Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I would like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, Dennis and Ruth Ann Walters, who have continually supported me throughout my academic and performing careers. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Douglas Fisher, who guided me through the development of this treatise. As I was working on this project, I found that I needed to raise my levels of score analysis and analytical thinking. Without Professor Fisher’s patience and guidance this would have been very difficult. I would like to convey my appreciation to Professor Stanford Olsen, whose intuitive understanding of musical style at the highest levels and ability to communicate that understanding has been a major factor in elevating my own abilities as a teacher and as a performer. -

Jamie Barton & Angela Meade

A DEDICATION TO RUTH BADER GINSBURG JAMIE BARTON & ANGELA MEADE WITH JOHN KEENE, PIANO “Our very first duo recital together took place at Stage Director................................................................................................................David Gately the Supreme Court in November 2015, where Film Director...................................................................................................................Kyle Seago we performed at the invitation of Supreme Court Lighting Designer.............................................................................................................Connie Yun Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Production Stage Manager.........................................................................................Yasmine Kiss Assistant Stage Manager..................................................................................Adrienne Mendoza We were deeply honored to be asked and elated to have a chance to share with her how her work had impacted our lives. “Oh, rimembranza” from Act I of Norma .....……...……...….……... Vincenzo Bellini (1801–1835) That experience immediately became—and has remained—one of the high points in each Angela Meade and Jamie Barton of our careers. “Morrò, ma prima in grazia” from Un ballo in maschera .....……. Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) In this moment, we are mourning the tremendous loss that so many of us are feeling at Angela Meade Justice Ginsburg’s passing. And the timing is hitting home for us in a deeply personal way. “O don fatale” from Act -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

Info Tickets

Tickets SALES CALENDAR Macbeth, Messa da Requiem, Ernani, Fuoco di gioia, Concerto Valerij Gergiev (Parco Ducale) from 28 August 2020 online from 29 August 2020 Quartetto Prometeo, Gala Verdiano (Teatro Regio di Parma) from 10 September 2020 online from 11 September 2020 PROMOTIONS AND REDUCTIONS Subscribers to Festival Verdi 2019 can book tickets for Macbeth, Messa da Requiem and Ernani with a 10% reduction from July 1 to 17 at the Teatro Regio ticket office, by calling 0521 203999 or by sending an email to biglietteria@teatroregioparma. Reserved tickets (one for each season ticket) can be paid from August 26 to September 3, at the ticket office following requests order of arrival. Subscribers to the Festival Verdi 2019 are also reserved a 10% reduction for tickets for the symphonic concert directed by Valerij Gergiev, the concert of Quartetto Prometeo and the Gala verdiano, which will be put on sale from August 28, 2020. Subscribers to the Festival Verdi 2019 will be able to purchase a pre-emption subscription to the Festival Verdi 2021 in the terms that will be indicated subsequently. Subscribers to the Opera Season 2020 will be able to claim the right of first refusal to purchase tickets for all shows on August 26 and 27, 2020 24 TICKETS Macbeth, Messa da Requiem Ernani, Valerij Gergiev Full price S.T. holder*/Under 30 Stall - I sector € 110,00 € 99,00 Stall - II sector € 55,00 € 49,50 Gala Verdiano Full price S.T. holder*/Under 30 Stall € 75,00 € 67,50 Central Box € 70,00 € 63,00 Off-Centre Box € 65,00 € 58,50 Side Box € 60,00 € 54,00 Gallery € 35,00 € 31,50 Quartetto Prometeo Full price S.T. -

A Guide to Verdi's Requiem

A Guide to Verdi’s Requiem Created by Dr. Mary Jane Ayers You may have heard that over the last 29 years, texts of the mass. The purpose of the requiem the Sarasota Opera produced ALL of the mass is to ask God to give rest to the souls of operatic works of composer Guiseppi Verdi, the dead. The title “requiem” comes from the including some extremely famous ones, Aida, first word of the Latin phrase, Requiem Otello, and Falstaff. But Verdi, an amazing aeternam dona eis, Domine, (pronounced: reh- opera composer, is also responsible for the qui-em ay-tare-nahm doh-nah ay-ees, daw- creation of one of the most often performed mee-nay) which translates, Rest eternal grant religious works ever written, the Verdi them, Lord. Requiem. Like many of his operas, Verdi’s Requiem is written for a massive group of performers, including a double chorus, large orchestra, and four soloists: a soprano, a mezzo-soprano (a medium high female voice), a tenor, and a bass. Gregorian chant version of the beginning of a The solos written for the Requiem require Requiem, composed 10th century singers with rich, full, ‘operatic’ voices. So what is a requiem, and why would Verdi So why did Verdi decide to write a requiem choose to compose one? mass? In 1869, Verdi lost his friend, the great composer Giacomo Rossini. Verdi worked with other composers to cobble together a requiem with each composer writing a different section of the mass, but that did not work out. Four years later another friend died, and Verdi decided to keep what he had already composed and complete the rest of the entire requiem. -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Choral/Orchestral Concert

MUSIC CHORAL/ORCHESTRAL CONCERT Gaillard Municipal Auditorium June 5 at 7:30pm SPONSORED BY SOUTH CAROLINA BANK AND TRUST Joseph Flummerfelt, conductor Katharine Goeldner, mezzo-soprano Tyler Duncan, baritone Westminster Choir Joe Miller, director Charleston Symphony Orchestra Chorus Robert Taylor, director Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra PROGRAM Ave verum corpus, K 618 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91) From Quattro pezzi sacri (Four Sacred Pieces) Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) I. Ave Maria II. Stabat mater INTERMISSION Requiem, Op. 9 Maurice Duruflé (1902–86) I. Introit (Requiem aeternam) II. Kyrie eleison III. Offertory (Domine Jesu Christe) IV. Sanctus – Benedictus V. Pie Jesu VI. Agnus Dei VII. Communion (Lux aeterna) VIII. Libera me IX. In Paradisum PROGRAM NOTES Ave Maria and Stabat mater (Verdi) What are we to make of Verdi’s final works? All are sacred pieces, Ave verum corpus (Mozart) though Verdi was an ardent atheist. All have unstable harmonies The first half of this concert presents final works by two of the sometimes bordering on atonality, though Verdi was a supreme greatest composers of the 18th and 19th centuries. The exquisite lyricist. All are strikingly non-operatic, offering only a single, brief Mozart miniature Ave verum corpus was written only six months vocal solo (in the Te Deum, heard at the 2010 Festival), though before the composer’s death at age 35. A mere 46 bars, it is a Verdi was Italy’s greatest opera composer. Yet they premiered at summation of Mozart’s ability to say something profound in the the Paris Opera in 1898, and Toscanini conducted the first Italian simplest possible way. -

Verdi Requiem

Sunday, October 30, 2016, at 3:00 pm Pre-concert lecture by Andrew Shenton at 1:45 pm in the Stanley H. Kaplan Penthouse Verdi Requiem London Symphony Orchestra Gianandrea Noseda , Conductor Erika Grimaldi , Soprano Daniela Barcellona , Mezzo-Soprano Francesco Meli , Tenor Vitalij Kowaljow , Bass London Symphony Chorus Simon Halsey , Chorus Director VERDI Messa da Requiem (“Requiem Mass”) (1874) Requiem and Kyrie Dies irae Dies irae Tuba mirum Liber scriptus Quid sum miser Rex tremendae Recordare Ingemisco Confutatis Lacrymosa Offertorio Sanctus Agnus Dei Lux aeterna Libera me This performance is approximately 90 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. This performance is also part of the Great Performers Symphonic Masters series. Endowment support for Symphonic Masters is provided by the Leon Levy Fund. Endowment support is also provided by UBS. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. David Geffen Hall Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. WhiteLightFestival.org Support for Great Performers is provided by UPCOMING WHITE LIGHT FESTIVAL EVENTS: Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser, Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Saturday, November 5 at 4 pm in the Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center. Stanley H. Kaplan Penthouse White Light Conversation Public support is provided by the New York State Our Humanity: Past, Present, and Future Council on the Arts with the support of Governor John Schaefer , moderator Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Through the lenses of evolution, psychology, Legislature. religion, and art, this panel will provide fresh insight into the age-old question, “What makes us MetLife is the National Sponsor of Lincoln Center.