Il Trovatore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

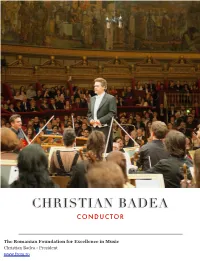

Christian Badea Conductor

CHRISTIAN BADEA CONDUCTOR The Romanian Foundation for Excellence in Music Christian Badea - President www.frem.ro Christian Badea has received exceptional acclaim throughout his career, which encompasses prestigious engagements in the foremost concert halls and opera houses of Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. Equally dividing his time between symphony and opera conducting, Christian Badea has appeared as a frequent guest in the major opera houses of the world. At the Metropolitan Opera in New York he conducted 167 performances in a wide variety of repertoire, including many of the MET international broadcasts. Among the opera houses where Christian Badea has guest conducted, are the Vienna State Opera, the Royal Opera House of Covent Garden in London, the Bayerische Staatsoper in München, the Staatsoper in Hamburg, the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf, the Grand Théâtre de Genève, the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, the Netherlands Opera in Amsterdam, the Royal Opera theaters in Copenhagen and Stockholm, the Oslo Opera, the Teatro Regio in Torino and the Teatro 1 Christian Badea at the Metropolitan Opera - New York Comunale in Bologna, the Opera National de Lyon and in North America - the opera companies of Houston, Dallas, Toronto, Montreal and Detroit. In recent years, Christian Badea has received great acclaim for his work at the Budapest State Opera (Tannhäuser, Der fliegende Holländer and Parsifal) , the Sydney Opera with new productions of Tosca, La bohème, Die tote Stadt, Otello and Falstaff, Oslo Opera – a new production of Tannhäuser, collaborating with stage director Stefan Herheim and Goteborg Opera – a new Don Carlo and Turandot. -

In Santa Cruz This Summer for Special Summer Encore Productions

Contact: Peter Koht (831) 420-5154 [email protected] Release Date: Immediate “THE MET: LIVE IN HD” IN SANTA CRUZ THIS SUMMER FOR SPECIAL SUMMER ENCORE PRODUCTIONS New York and Centennial, Colo. – July 1, 2010 – The Metropolitan Opera and NCM Fathom present a series of four encore performances from the historic archives of the Peabody Award- winning The Met: Live in HD series in select movie theaters nationwide, including the Cinema 9 in Downtown Santa Cruz. Since 2006, NCM Fathom and The Metropolitan Opera have partnered to bring classic operatic performances to movie screens across America live with The Met: Live in HD series. The first Live in HD event was seen in 56 theaters in December 2006. Fathom has since expanded its participating theater footprint which now reaches more than 500 movie theaters in the United States. We’re thrilled to see these world class performances offered right here in downtown Santa Cruz,” said councilmember Cynthia Mathews. “We know there’s a dedicated base of local opera fans and a strong regional audience for these broadcasts. Now, thanks to contemporary technology and a creative partnership, the Metropolitan Opera performances will become a valuable addition to our already stellar lineup of visual and performing arts.” Tickets for The Met: Live in HD 2010 Summer Encores, shown in theaters on Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. in all time zones and select Thursday matinees, are available at www.FathomEvents.com or by visiting the Regal Cinema’s box office. This summer’s series will feature: . Eugene Onegin – Wednesday, July 7 and Thursday, July 8– Soprano Renée Fleming and baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky star in Tchaikovsky’s lushly romantic masterpiece about mistimed love. -

Libretto Nabucco.Indd

Nabucco Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI major partner main sponsor media partner Il Festival Verdi è realizzato anche grazie al sostegno e la collaborazione di Soci fondatori Consiglio di Amministrazione Presidente Sindaco di Parma Pietro Vignali Membri del Consiglio di Amministrazione Vincenzo Bernazzoli Paolo Cavalieri Alberto Chiesi Francesco Luisi Maurizio Marchetti Carlo Salvatori Sovrintendente Mauro Meli Direttore Musicale Yuri Temirkanov Segretario generale Gianfranco Carra Presidente del Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Revisori Nicola Bianchi Andrea Frattini Nabucco Dramma lirico in quattro parti su libretto di Temistocle Solera dal dramma Nabuchodonosor di Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois e Francis Cornu e dal ballo Nabucodonosor di Antonio Cortesi Musica di GIUSEPPE V ERDI Mesopotamia, Tavoletta con scrittura cuneiforme La trama dell’opera Parte prima - Gerusalemme All’interno del tempio di Gerusalemme, i Leviti e il popolo lamen- tano la triste sorte degli Ebrei, sconfitti dal re di Babilonia Nabucco, alle porte della città. Il gran pontefice Zaccaria rincuora la sua gente. In mano ebrea è tenuta come ostaggio la figlia di Nabucco, Fenena, la cui custodia Zaccaria affida a Ismaele, nipote del re di Gerusalemme. Questi, tuttavia, promette alla giovane di restituirle la libertà, perché un giorno a Babilonia egli stesso, prigioniero, era stato liberato da Fe- nena. I due innamorati stanno organizzando la fuga, quando giunge nel tempio Abigaille, supposta figlia di Nabucco, a comando di una schiera di Babilonesi. Anch’essa è innamorata di Ismaele e minaccia Fenena di riferire al padre che ella ha tentato di fuggire con uno stra- niero; infine si dichiara disposta a tacere a patto che Ismaele rinunci alla giovane. -

San Francisco Opera Center and Merola Opera Program Announce 2020 Schwabacher Recital Series

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA CENTER AND MEROLA OPERA PROGRAM ANNOUNCE 2020 SCHWABACHER RECITAL SERIES January 29 Kicks Off First of Four Recitals Highlighting Emerging Artists and Unique Musical Programs Tickets available at sfopera.com/srs and (415) 864-3330 SAN FRANCISCO, CA (January 6, 2019) — Now in its 37th year, the Schwabacher Recital Series returns on Wednesday, January 29, with performances at San Francisco’s Dianne and Tad Taube Atrium Theater that feature emerging artists from around the globe. Presented by San Francisco Opera Center and Merola Opera Program, the annual Schwabacher Series consists of four Wednesday evening recitals, the last of which concludes on April 22. The first-ever Schwabacher series was presented in December 1983, kicking off a decades-long San Francisco tradition of presenting rising international talent in the intimacy of a recital setting. The 2020 series will blend classics like Hector Berlioz’s Les Nuits d’Été with rarely performed 20th- and 21st-century works like Olivier Messiaen’s Harawi. JANUARY 29: ALICE CHUNG, LAUREANO QUANT AND NICHOLAS ROEHLER (From left to right: Alice Chung, Laureano Quant and Nicholas Roehler) The series opens on January 29 with a set of performers recently seen as part of the Merola Opera Program: mezzo-soprano Alice Chung, baritone Laureano Quant and pianist Nicholas Roehler. Twice named as a Merola artist—once in 2017 and again in 2019—Chung returns to the 1 Bay Area for this recital, having been hailed as a “force of nature” by San Francisco Classical Voice (SFCV). She will tackle a range of works, from Colombian composer Luis Carlos Figueroa’s soothing lullaby “Berceuse” to cabaret-inspired works like William Bolcom’s “Over the Piano.” Quant, a 2019 Merola participant, joins Chung to perform Bolcom’s music, as well as select songs from Berlioz’s Les Nuits d’Été and Francesco Santoliquido’s I Canti della Sera. -

VIVA VERDI a Small Tribute to a Great Man, Composer, Italian

VIVA VERDI A small tribute to a great man, composer, Italian. Giuseppe Verdi • What do you know about Giuseppe Verdi? What does modern Western society offer everyday about him and his works? Plenty more than you would think. • Commercials with his most famous arias, such as “La donna e` nobile”, from Rigoletto, are invading the air time of television… • Movies and cartoons have also plenty of his arias… What about stamps from all over the world carrying his image? • There are hundreds of them…. and coins and medals… …and banknotes? Well, those only in Italy, that I know of…. Statues of him are all over the world… ….and we have Verdi Squares and Verdi Streets And let’s not forget the many theaters with his name… His operas even became comic books… • Well, he was a famous composer… but it’s that the only reason? Let’s look into that… Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi Born Joseph Fortunin François Verdi on October 10, 1813 in a village near Busseto, in Emilia Romagna, at the time part of the First French Empire. He was therefore born French! Giuseppe Verdi He was refused admission by the Conservatory of Milan because he did not have enough talent… …that Conservatory now carries his name. In Busseto, Verdi met Antonio Barezzi, a local merchant and music lover, who became his patron, financed some of his studies and helped him throughout the dark years… Thanks to Barezzi, Verdi went to Milano to take private lessons. He then returned to his town, where he became the town music master. -

CHAN 3036 BOOK COVER.Qxd 22/8/07 2:50 Pm Page 1

CHAN 3036 BOOK COVER.qxd 22/8/07 2:50 pm Page 1 CHAN 3036(2) CHANDOS O PERA I N ENGLISH Il Trovatore David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION CHAN 3036 BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 3:15 pm Page 2 Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) Il trovatore (The Troubadour) Opera in four parts AKG Text by Salvatore Cammarano, from the drama El trovador by Antonio Garcia Gutiérrez English translation by Tom Hammond Count di Luna, a young nobleman of Aragon ....................................................................Alan Opie baritone Ferrando, captain of the Count’s guard ..................................................................................Clive Bayley bass Doña Leonora, lady-in-waiting to the Princess of Aragon ..............................................Sharon Sweet soprano Inez, confidante of Leonora ........................................................................................Helen Williams soprano Azucena, a gipsy woman from Biscay ....................................................................Anne Mason mezzo-soprano Manrico (The Troubadour), supposed son of Azucena, a rebel under Prince Urgel ........Dennis O’Neill tenor Ruiz, a soldier in Manrico’s service ..................................................................................Marc Le Brocq tenor A Gipsy, a Messenger, Servants and Retainers of the Count, Followers of Manrico, Soldiers, Gipsies, Nuns, Guards Geoffrey Mitchell Choir London Philharmonic Orchestra Nicholas Kok and Gareth Hancock assistant conductors David Parry Further appearances in Opera in English Dennis O’Neill: -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

ARSC Journal

TOSCANINI LIVE BEETHOVEN: Missa Solemnis in D, Op. 123. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Alexander Kipnis, bass; Westminster Choir; VERDI: Missa da Requiem. Zinka Milanov, soprano; Bruna Castagna, mezzo-soprano; Jussi Bjoerling, tenor; Nicola Moscona, bass; Westminster Choir, NBC Symphony Orchestra, Arturo Toscanini, cond. Melodram MEL 006 (3). (Three Discs). (Mono). BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125. Vina Bovy, soprano; Kerstin Thorborg, contralto; Jan Peerce, tenor; Ezio Pinza, bass; Schola Cantorum; Arturo Toscanini Recordings Association ATRA 3007. (Mono). (Distributed by Discocorp). BRAHMS: Symphonies: No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; No. 2 in D, Op. 73; No. 3 in F, Op. 90; No. 4 in E Minor, Op. 98; Tragic Overture, Op. 81; Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56A. Philharmonia Orchestra. Cetra Documents. Documents DOC 52. (Four Discs). (Mono). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68; Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2 in B Flat, Op. 83. Serenade No. 1 in D, Op. 11: First movement only; Vladimir Horowitz, piano (in the Concerto); Melodram MEL 229 (Two Discs). BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68. MOZART: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550. TCHAIKOVSKY: Romeo and Juliet (Overture-Fantasy). WAGNER: Lohengrin Prelude to Act I. WEBER: Euryanthe Overture. Giuseppe Di Stefano Presenta GDS 5001 (Two Discs). (Mono). MOZART: Symphony No. 35 in D, K. 385 ("Haffner") Rehearsal. Relief 831 (Mono). TOSCANINI IN CONCERT: Dell 'Arte DA 9016 (Mono). Bizet: Carmen Suite. Catalani: La Wally: Prelude; Lorelei: Dance of the Water ~· H~rold: Zampa Overture. -

1 CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se Incluye Un Listado Con Las

CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se incluye un listado con las representaciones de Aida, de Giuseppe Verdi, en la historia del Gran Teatre del Liceu. Estreno absoluto: Ópera del Cairo, 24 de diciembre de 1871. Estreno en Barcelona: Teatro Principal, 16 abril 1876. Estreno en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 25 febrero 1877 Última representación en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 30 julio 2012 Número total de representaciones: 454 TEMPORADA 1876-1877 Número de representaciones: 21 Número histórico: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Fechas: 25 febrero / 3, 4, 7, 10, 15, 18, 19, 22, 25 marzo / 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 18, 22, 27 abril / 2, 10, 15 mayo 1877. Il re: Pietro Milesi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Carolina de Cepeda (febrero, marzo) Teresina Singer (abril, mayo) Radamès: Francesco Tamagno Ramfis: Francesc Uetam (febrero y 3, 4, 7, 10, 15 marzo) Agustí Rodas (a partir del 18 de marzo) Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Argimiro Bertocchi Director: Eusebi Dalmau TEMPORADA 1877-1878 Número de representaciones: 15 Número histórico: 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Fechas: 29 diciembre 1877 / 1, 3, 6, 10, 13, 23, 25, 27, 31 enero / 2, 20, 24 febrero / 6, 25 marzo 1878. Il re: Raffaele D’Ottavi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Adele Bianchi-Montaldo Radamès: Carlo Bulterini Ramfis: Antoine Vidal Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Antoni Majjà Director: Eusebi Dalmau 1 7-IV-1878 Cancelación de ”Aida” por indisposición de Carlo Bulterini. -

Verdi Aïda (Highlights) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Verdi Aïda (Highlights) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical / Stage & Screen Album: Aïda (Highlights) Country: UK Released: 1962 Style: Opera MP3 version RAR size: 1594 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1121 mb WMA version RAR size: 1506 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 405 Other Formats: DXD AA AU ADX WMA AC3 DTS Tracklist Act I A1 Si: Corre Voce / Celeste Aida A2 Ritorna Vincitori Act III A3 Qui Radamès Verra / O Patria Mia / Cieli Mio Padre / Pur Ti Riveggo Act III B1 Nel Fiero Adunansi Act IV B2 Già I Sacerdoti Adunansi B3 La Fatal Pietra Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Radio Corporation Of America Copyright (c) – The Decca Record Company Limited Credits Baritone Vocals [Amonasro] – Giorgio Tozzi, Robert Merrill Chorus – Rome Opera House Chorus* Chorus Master – Giuseppe Conca Composed By – Verdi* Conductor – Georg Solti Liner Notes – Francis Robinson Mezzo-soprano Vocals [Amneris] – Rita Gorr Orchestra – Rome Opera House Orchestra* Soprano Vocals [Aida] – Leontyne Price Tenor Vocals [Radamès] – Jon Vickers Notes Stereo release of RB-6531 Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Label side A): N2RY-2713 Matrix / Runout (Label side B): N2RY-2714 Matrix / Runout (Runout side A): N2RY-2713-1G Matrix / Runout (Runout side B): N2RY-2714-2G Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Verdi*, Solti* RCA Verdi*, Solti* Conducting Rome Victor Conducting Rome Opera House Red Opera House LSC 2616, Orchestra* And Seal, LSC 2616, Orchestra* And US 1962 LSC-2616 Chorus*, Price*, RCA LSC-2616 Chorus*, Price*, -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No.