How Many Times Must the Question Be Answered? the Application of the Learned Intermediary Doctrine in the Norplant Contraceptive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unavoidably Unsafe Products and Strict Products Liability: What Liability Rule Should Be Applied to the Sellers of Pharmaceutical Products? Richard C

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 78 | Issue 4 Article 3 1990 Unavoidably Unsafe Products and Strict Products Liability: What Liability Rule Should be Applied to the Sellers of Pharmaceutical Products? Richard C. Ausness University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Food and Drug Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Ausness, Richard C. (1990) "Unavoidably Unsafe Products and Strict Products Liability: What Liability Rule Should be Applied to the Sellers of Pharmaceutical Products?," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 78 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol78/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kentucky Law Journal Volume 78 1989-90 Number 4 Unavoidably Unsafe Products and Strict Products Liability: What Liability Rule Should be Applied to the Sellers of Pharmaceutical Products? BY RICHARD C. AusNEss* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................... 706 I. OVERVIEW ................................ 709 A. Strict Products Liability .............................. 709 B. Comment K and "Unavoidably Unsafe" Products ................................................... 712 II. COM[ENT K's LIABILITY REGm .......................... 719 A. Risks Associated with the Production Process. 720 B. Risks Arising from the Inherent Nature of a Product .................................................... 723 C. Risks Created by Conscious Design Choices .... 726 D. Scientifically Unknowable Risks ................... 731 E. -

05/01/02 Louisiana Medicaid Management

APPENDIX C 05/01/02 LOUISIANA MEDICAID MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEM PAGE 1 DEPT OF HEALTH AND HOSPITALS - BUREAU OF HEALTH SERVICES FINANCING LOUISIANA MEDICAID PHARMACY BENEFITS MANAGEMENT UNIT ONLY THESE COMPANIES PRODUCTS ARE COVERED AND ONLY THOSE DOSAGE FORMS LISTED IN APPENDIX A. MEDICAID DRUG FEDERAL REBATE PARTICIPATING PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES LABELER PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY EFFECTIVE END DATE CODE DATE 00002 ELI LILLY & CO 04/01/91 00003 E.R.SQUIBB & SONS,INC 04/01/91 00004 HOFFMAN-LA ROCHE,INC 04/01/91 00005 LEDERLE LABORATORIES AMERICAN CYANAMID 04/01/91 00006 MERCK SHARP & DOHME 04/01/91 00007 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM CORPORATION 04/01/91 00008 WYETH LABORATORIES 04/01/91 00009 THE UPJOHN COMPANY 04/01/91 00011 BECTON DICKINSON MICROBIOLOGY SYSTEMS 10/01/91 07/01/98 00013 ADRIA LABORATORIES DIV.OF ERBAMONT,INC 04/01/91 00014 G.D.SEARLE & CO 04/01/91 01/01/01 00015 MEAD JOHNSON & COMPANY 04/01/91 00016 KABI PHARMACIA 04/01/91 00021 REED & CARNRICK 10/01/96 01/01/97 00023 ALLERGAN,INC 04/01/91 00024 WINTHROP PHARMACEUTICALS 04/01/91 00025 G.D.SEARLE & CO 04/01/91 00026 MILES INC.,PHARMACEUTICAL DIVISION 04/01/91 00028 GEIGY PHARMACEUTICALS 04/01/91 00029 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM CORPORATION 04/01/91 00031 ROBINS,A.H. 04/01/91 00032 SOLVAY PHARMACEUTICALS 04/01/91 00033 SYNTEX 04/01/91 00034 THE PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY 04/01/91 00037 CARTER-WALLACE,INC 04/01/91 00038 STUART PHARMACEUTICALS,ICI AMERICAS INC 04/01/91 07/01/01 00039 HOECHST-ROUSSEL PHARMACEUTICALS INC 04/01/91 00043 SANDOZ CONSUMER CORPORATION 04/01/91 00044 KNOLL PHARMACEUTICALS -

Health Industry Business Communications Council

Health Industry Business Communications Council Registered Labelers: Accredited Auto-ID Labeling Standards Argentina New MedTek Devices Pty Ltd Oxavita SRL Norseld Pty Ltd. Novadien Healthcare Pty Ltd The following companies Odontit S.A. (and/or their subsidiaries/ PAMPAMED S.R.L. Numedico Technologies Pty Ltd divisions) have applied PATEJIM SRL Opto Global Pty. Ltd. for a Labeler Identification Orthocell Limited Code (LIC) assignment with Austria Prolotus Technologies Pty Ltd HIBCC*. By doing so, they afreeze GmbH Red Milawa Pty Ltd dba Magic Mobility have demonstrated their AMI GmbH SDI Limited commitment to patient safety Bender Medsystems GmbH Signostics Ltd. and logistical efficiency for BHS Technologies GmbH Sirtex Medical Pty Ltd their customers, the industry Metasys Medizintechnik GmbH Smith & Nephew Surgical Pty. Ltd. and the public at large. PAA Laboratories GmbH Staminalift International Limited Safersonic Medizinprodukte Handels The Pipette Company Pty. Ltd. Any organization that is GmbH Thermo Electron Corporation interested in using the HIBC W & H Dentalwerk Burmoos GmbH Vush Pty Ltd uniform labeling system may apply for the assignment of VUSH STIMULATION Australia one or more LICs. William A Cook Australia Pty. Ltd. Adv. Surgical Design & Manufacture, Ltd. Last updated 9-21-2021 AirPhysio Pty Ltd Belgium Annalise-AI Pty Ltd 3M Europe Apollo Medical Imaging Technology Pty Advanced Medical Diagnostics SA/NV Ltd Analis SA/NV Benra Pty Ltd dba Gelflex Laboratories Baxter World Trade Bioclone Australia Pty. Ltd. Bio-Rad RSL Candelis, Inc. Bio-Rad Lab Inc Clinical Diag. Group DePuy Australia Pty. Ltd. Biosource Europe SA For more information, please dorsaVi Ltd Cilag NV contact the HIBCC office at: EC Certification Service GmbH Coris Bioconcept Fink Engineering Pty Ltd Fuji Hunt Photographic Chemicals NV 2525 E. -

Sponsor List

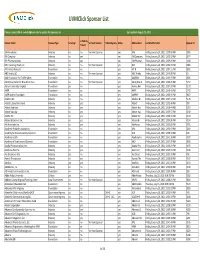

UVMClick Sponsor List Please contact SPA at [email protected] to update the Sponsor List last updated August 24, 2021 Is Publicly Sponsor Name Sponsor Type Is Foreign Vermont Sponsor Federal Agency Active Abbreviation Last Modified Date Sponsor ID Traded 106 Associates Industry no no Vermont Sponsor yes 106 Friday, January 29, 2021 12:35:03 PM 3385 3M Company Industry no yes yes 3M Company Friday, January 29, 2021 12:32:32 PM 2877 3M Pharmaceuticals Industry no yes yes 3M Pharmac Friday, January 29, 2021 12:39:23 PM 4188 835 Hinesburg Road, LLC Industry no no Vermont Sponsor yes 835 Friday, January 29, 2021 12:32:33 PM 3386 A Territory Resource Foundation no no yes A.T.R. Friday, January 29, 2021 12:34:11 PM 3805 A&C Realty LLC. Industry no no Vermont Sponsor yes A&C Realty Friday, January 29, 2021 12:40:28 PM 60 AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety Foundation no no yes AAAFDN Friday, January 29, 2021 12:36:49 PM 3806 AALV/New Farms for New Americans Foundation no no Vermont Sponsor yes AALV/New FFriday, January 29, 2021 12:32:25 PM 5154 Aarhus University Hospital Foundation yes no yes Aarhus Uni Friday, January 29, 2021 12:34:23 PM 5172 AARP Foundation no no yes AARP Friday, January 29, 2021 12:40:40 PM 2742 AARP Andrus Foundation Foundation no no yes AARPAF Friday, January 29, 2021 12:36:35 PM 3807 Abalone Bio Industry no no yes Abalone Bi Friday, January 29, 2021 12:37:14 PM 5178 Abbott Laboratories Fund Industry no yes yes Abbott Friday, January 29, 2021 12:32:46 PM 309 Abbott Nutrition Industry no yes yes Abbott Nut Friday, January 29, 2021 12:38:44 PM 5219 Abbott Vascular Industry no yes yes Abbott Vas Friday, January 29, 2021 12:35:57 PM 4192 AbbVie Inc. -

Eric M. White, O.D., Inc

ERIC M. WHITE, O.D., INC . 5075 Ruffin Road Suite B, San Diego, CA 92123 (858) 278-4720 Toll Free (866) 458-2062 FAX (858) 278-3640 [email protected] www.drericwhite.com California License #8611T STATEMENT OF CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION June 1982 Bachelor of Arts, Physiological Psychology University of California, San Diego; San Diego, California. May 1984 Bachelor of Science, Visual Science Southern California College of Optometry; Fullerton, California. May 1986 Doctor of Optometry Southern California College of Optometry; Fullerton, California. PRIVATE PRACTICE 1986 - 1989 Partnership; D.M. Rasmussen, O.D., F.A.A.O., Mission Village Medical Center, 3303 Ruffin Road, San Diego, California. 1989-2001 Private Practice Mission Village Medical Center, 3303 Ruffin Road, San Diego, California. 2001-Present Private Practice 5075 Ruffin Road, Suite B, San Diego, California CLINICAL ROTATIONS 1985 Southern California College of Optometry; Fullerton, California . Provided comprehensive vision care including contact lenses, vision therapy, low vision, ocular photography, electrodiagnostic services, auto perimetry, and disease detection. 1985 San Bernardino Juvenile Hall; San Bernardino, California. Provided screening and treatment of vision and learning disabilities among juveniles. 1985 D.M. Rasmussen, O.D., F.A.A.O.; San Diego, California. Assisted doctor on investigational studies, comprehensive vision care, contact lenses, low vision, autoperimetry, and disease detection . INTERNSHIP 1986 United States Naval Submarine Base, San Diego, California. Provided comprehensive vision care including fitting and care for extended wear contact lenses. 1986 U.S. Naval Medical Corps. Marine Corps Recruit Depot; San Diego, California. Provided comprehensive vision care including disease detection. 1986 Balboa Regional Naval Hospital San Diego, California. -

Pharmaceutical Company Contact Information (PDF)

Pharmaceutical Company Contact Information - Rebate Filing - as of June 2018 Labeler Name Invoice Contact Phone Extension 00002 LILLY USA, LLC LISA NORTON (317) 276-2000 00003 ER SQUIBB AND SONS INC. LYNN LEWIS (609) 897-4731 00004 GENENTECH CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION (650) 866-2666 00005 LEDERLE LABORATORIES DAN MAGUIRE (484) 563-5097 00006 MERCK & CO., INC. DOUG BICKFORD (215) 652-0671 00007 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM DAVID BUCKLEY (215) 751-5690 00008 WYETH LABORATORIES JENNIFER WOOTEN (901) 215-1883 00009 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN COMPANY/PFIZER JENNIFER WOOTEN (901) 215-1883 00013 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN COMPANY NICHOLAS CHRISTODOULOU (336) 291-1053 00014 G. D. SEARLE & CO. CINDY MCDONALD (847) 581-5726 00015 MEAD JOHNSON AND COMPANY LYNN LEWIS (609) 897-4731 00016 PHARMACIA INC. BARBARA WINGET (908) 901-7254 00023 ALLERGAN INC SHOBHANA MINAWALA (714) 246-6205 00024 SANOFI WINTHROP PHARMACEUTICALS LAURIE DUNLAP, ADMIN., GOVT. OPERATIONS (212) 551-4198 00025 PHARMACIA CORPORATION NICHOLAS CHRISTODOULOU (336) 291-1053 00026 BAYER CORPORATION PHARMACEUTICAL DIV. LINDA WOLCHESKI (203) 812-6372 00028 NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS (862) 778-8094 00029 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM DAVID BUCKLEY (215) 751-5690 00031 A. H. ROBINS COMPANY DAN MAGUIRE (610) 902-3222 00032 SOLVAY PHARMACEUTICALS STACEY LENOX (847) 937-3979 00033 SYNTEX LABORATORIES, INC. JANICE BRENNAN (973) 562-3494 00034 THE PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY JUNE STOWE (203) 899-8035 00037 CARTER-WALLACE, INC. JAY R BRENNAN (609) 655-6163 00038 ASTRAZENECA LP DAVID WRIGHT (302) 886-2268 7820 00039 AVENTIS PHARMACEUTICALS (908) 981-7461 00043 NOVARTIS CONSUMER HEALTH, INC. EDWARD D. COLLINS (973) 781-6191 00044 KNOLL LABORATORIES DEBRA DEYOUNG (847) 937-4372 00045 MCNEIL PHARMACEUTICAL (908) 218-6777 00046 AYERST LABORATORIES (901) 215-1473 00047 WARNER CHILCOTT LABORATORIES LISA KAROLCHYK (973) 442-3262 00048 KNOLL PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY DEBRA DEYOUNG (847) 937-4372 00049 ROERIG NICHOLAS CHRISTODOULOU (336) 291-1053 00051 UNIMED PHARMACEUTICALS, INC STACY LENOX (847) 937-3979 00052 ORGANON, USA, INC. -

Dr. Richard Rozek

Dear Ms. Overstreet: I am interested in being considered for the vacancy on the Glynn Brunswick Memorial Hospital Authority. Per the instructions with the vacancy announcement, I attached a copy of my vita to the letter. I am an economist with a specialty in health care economics. I have worked on competition, regulation, contract, and tax issues in health care during my career in academic, federal government, and private sector positions. I have written articles on health care issues and testified in major health care litigations. I have owned a home on Jekyll Island since 1993. Please let me know if you need additional information. Sincerely, Richard P. Rozek, Ph.D. RICHARD P. ROZEK, PH.D. CONTACT INFORMATION Redacted Jekyll Island, GA 31527 Phone: 912 Redacted Redacted gmail.com BACKGROUND Dr. Rozek received a B.A. degree in Mathematics with honors from the College of St. Thomas, a M.A. degree in Mathematics from the University of Minnesota, and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Economics from the University of Iowa. Dr. Rozek began his professional career as an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh where he taught courses in industrial organization, mathematical economics, and microeconomic theory. Dr. Rozek then worked for over six years in the Bureau of Economics at the Federal Trade Commission in a series of senior staff positions including Deputy Assistant Director for Antitrust. While at the FTC, Dr. Rozek evaluated antitrust and regulatory issues in electric and gas utilities, oil pipelines, soft drinks, for-profit and nonprofit hospitals, motion pictures, pharmaceuticals, and information industries. -

Marie-Ève Arbour*

McGill Law Journal — Revue de droit de McGill PORTRAIT OF DEVELOPMENT RISK AS A YOUNG DEFENCE Marie-Ève Arbour* Since its (recent) insertion into the vocab- Depuis son insertion (récente) dans la ulary of jurists, development risk has piqued langue des juristes, le risque de développement the curiosity of experts in defective products li- suscite la curiosité des experts de la responsabi- ability. An investigation into development risk’s lité du fait des produits défectueux. Pourtant, scope and reach, however, requires a compara- une reconstruction de sa portée et de son éten- tive analysis that brings out the issues it raises due ne semble pouvoir s’effectuer qu’au prix and the ambiguities it has occasioned. In this d’une analyse comparative destinée à mettre en light, this article draws support from abundant relief les enjeux qu’il soulève et les ambiguïtés doctrine, and, perhaps paradoxically, scant ju- qu’il fait naître. Dans cette optique, la présente risprudence on the subject, in an effort to contribution prend appui sur l’abondante doc- sketch, in broad strokes, a contemporary por- trine à son sujet, et, peut-être paradoxalement, trait of development risk. la rare jurisprudence l’ayant abordé, afin d’esquisser, à grands traits, un portrait contem- porain du risque de développement. * Professor of civil law, Laval University (Québec). I am particularly thankful to Lara Khoury and Etienne Vergès for their outstanding endeavour and to my peer reviewers for their thorough and helpful comments. I would also like to acknowledge the stimulat- ing hospitality I encountered amidst the books and shelves of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies (University of London) and the European University Institute (Florence). -

Intellectual Property in Molecular Medicine

This is a free sample of content from Intellectual Property in Molecular Medicine. Click here for more information on how to buy the book. Index A Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 11, 93–95 Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), litigation, Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., 173 59–73 Arkansas Carpenters Health & Welfare Fund v. ACIP. See Advisory Council on Intellectual Property Boyer AG,64 Acromed Corp. v. Sofamor Danek Group, Inc., 84, 87–88 Association for Molecular Pathology et al. v. Myriad Advisory Council on Intellectual Property (ACIP), 232 Genetics, 127–128, 132–136, 139–140, Aerospace America, Inc. v. Abatement Technologies, Inc.,3 149–150, 157, 164, 167–170, 172–173, AIA. See America Invents Act 176–179, 210–212, 241–242 Ajinomoto Co., Inc. v. Archer-Daniels-Midland Co.,6 The Association for Molecular Pathology & Ors v. United Akamai Technologies, Inc. v. Limelight Networks, Inc., 186 States Patent and Trademark Office and Altana PharmaAG v. Tevs Pharms. USA, Inc., 112 Myriad Genetics, 157 America Invents Act (AIA) Association for Molecular Pathology v. Unites States Patent CREATE Act expansion, 23–27 and Trademark Office and Myriad, 241 disclosure and claiming requirements Astra Aktiebolag v. Adrx Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 119, 124 claim requirements in Section 112, 12–13 Atlas Powder, Co. v. Ireco, Inc., 116 overview, 10 Australia Patent Office (APO) specification requirements in Section 112, 10–12 genetic material patents first-inventor-to-file, 16–17 activity, 154 inventorship, 90 consideration, 153–154 nonobviousness of invention, 9–10, 104 debate, 154–155 novelty of invention, 7–9 example claims, 160 overview, 15–16 infringement of the term “isolated”, 157–158 patent recipient eligibility, 6–7 legislative change proposals, 158–159 prior art manner of manufacture, 156–157 definition Myriad litigation, 155–156, 158 implications, 22 Patents Act amendments, 159 Section 102(a)(1), 17–18 prospects, 160–161 Section 102(a)(2), 19–21 patentable inventions, 151–153, 227–229 exceptions stem cell. -

Products Liability

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 8 1986 Products Liability: The onC tinued Viability of the Learned Intermediary Rule as it Applies to Product Warnings for Prescription Drugs Barbara Pope Flannagan University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the Medical Jurisprudence Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Barbara P. Flannagan, Products Liability: The Continued Viability of the Learned Intermediary Rule as it Applies to Product Warnings for Prescription Drugs, 20 U. Rich. L. Rev. 405 (1986). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol20/iss2/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PRODUCTS LIABILITY: THE CONTINUED VIABILITY OF THE LEARNED INTERMEDIARY RULE AS IT APPLIES TO PRODUCT WARNINGS FOR PRESCRIPTION DRUGS Judicial decisions," as well as statutory enactments,2 have removed many of the traditional stumbling blocks which formerly hampered an injured plaintiff's recovery against the manufacturer of a defective prod- uct. Concomitantly, the past few decades have seen a dramatic increase in the number of product liability suits brought by injured consumers di- rectly against manufacturers.3 These product liability suits have involved 1. Absent fraud, early nineteenth century consumers had no cause of action against the manufacturer or seller of a defective product under any theory, contract or tort. W. KEETON, PROSSER & KEETON ON TORTS § 95A, at 679 (5th ed. -

UR-Coeus Sponsor List

UR-Coeus Sponsor Table (alphabetical by sponsor name) Sponsor Sponsor Code Sponsor Type 2138 21st Century Medicine CORP Sponsor Type Key 1 3M CORP CORP = Corporate 3803 4S3 Bioscience Inc CORP FED = Federal 5207 A. F. Associates Family Medicine ONFA FND = Foundation 2602 A. P. Pharma CORP IND = Individuals 2 A.L. Mailman Foundation FND NYS = New York State 2023 AA Implant Dentistry Research Foundation ONFA OLG = Other Local Gov't 3 AAA Fnd for Traffic Safety ONFA ONFA = Other Non-Fed Agency 2329 aaiPharma Inc CORP VHA = Voluntary Health Agency 3257 Aamjiwnaang First Nations Community ONFA 5345 Aarhus University Hospital ONFA 3713 Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc. ONFA 4 AARP Andrus Fdn FND 3853 AB Sciences CORP 3378 AB Vector, Inc CORP 899 Abbott Diagnostics CORP 3864 Abbott Fund FND 14 Abbott Laboratories CORP 5126 AbbVie, Inc. CORP 5854 Abeona Therapeutics CORP 5063 Abington Medical Specialists ONFA 5331 Abington Memorial Hospital ONFA 2835 ABIOMED, Inc. CORP 3687 Ablation Frontiers CORP 5118 Ablynx NV CORP 2053 ABMRF/Fnd for Alcohol Research ONFA 2171 Abortion Rights Mobilization ONFA 3361 Abraxix BioScience, LLC CORP 4953 Abt Associates, Inc. CORP 5037 Academic Gastrointestinal Cancer Consortium ONFA 15 Academic Med Ctr Cons ONFA 3733 Academic Pediatric Association ONFA 3160 Academy of Orofacial Pain ONFA 2122 Academy of Prosthodontics Foundation ONFA 3663 Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc. CORP 3273 Accelerate Brain Cancer Cure ONFA 5584 Acceleron Pharma Inc. CORP 5601 Accelovance, Inc. CORP 5940 Accreditation Council Grad Med Educ ONFA 5832 Accriva Diagnostics CORP 3888 AccuGenomics, Inc. CORP 5656 Acerta Pharma CORP 6101 Acessa Health, Inc. -

TEKLA LIFE SCIENCES INVESTORS 100 Federal Street, 19Th Floor Boston, Massachusetts 02110 (617) 772-8500

Merrill Corp - Tekla Life Sciences Investors [HQL] Proxy Statements [Funds] 04-22-2019 ED [AUX] | ascott | 09-Apr-19 12:24 | 19-3008-4.aa | Sequence: 1 CHKSUM Content: 14312 Layout: 53493 Graphics: 51433 CLEAN TEKLA LIFE SCIENCES INVESTORS 100 Federal Street, 19th Floor Boston, Massachusetts 02110 (617) 772-8500 NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS To the Shareholders of TEKLA LIFE SCIENCES INVESTORS: An Annual Meeting of Shareholders of Tekla Life Sciences Investors (“HQL”) (the“Fund”) will be held on Thursday, June 13, 2019 at 9:00 a.m. at the offices of Dechert LLP, One International Place, 100 Oliver Street, 40th Floor, Boston, Massachusetts 02110, for the following purposes: (1) The election of Trustees of the Fund; (2) The ratification or rejection of the selection of Deloitte & Touche LLP as the independent registered public accountants of the Fund for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2019; (3) Take action on a shareholder proposal requesting that the Fund take the steps necessary to reorganize the Board of Trustees into one class with each Trustee subject to election each year, if properly presented at the meeting; and (4) The transaction of such other business as may properly come before the Annual Meeting and any adjournment(s) or postponement(s) thereof. If you have any questions about the proposals to be voted on, please call our solicitor, Okapi Partners, at (877)279-2311. The Board of Trustees of the Fund recommends that shareholders vote FOR the election of all nominees for election as Trustees, FOR the selection of Deloitte & Touche LLP as the independent registered accountants of the Fund and AGAINST the shareholder proposal.