Maccabees, Zealots and Josephus: Not Merely Popular, Legitimation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCSE --- Reviewbackgroundgospel

Review: Background to the Gospel 1 Choosing the best ending, write a sentence each for the following. The Roman allowed the Jews what privilege? Which religious party at the time of Jesus A Romans never sentenced Jews to death accepted these books as their only rule of life? B Jews didn’t have to pay taxes to Rome A Sadducees C Jews were excused from serving in the B Pharisees Roman army C Zealots Which two dates approximate to the times when Pharisee ‘ separated one’ implies that they Solomon's Temple and Herod's Temple were A resisted all pagan influences on Judaism. destroyed? B lived alone as hermits in the hills. A 1200 BC, 70 BC C never mixed with the Sadducees. B 440 BC, 120 AD C 586 BC, 70 AD Most scribes were also A Pharisees. What was the major duty of the priests of the B Sadducees. Temple? C Zealots. A to pray B to collect Temple taxes Between which two groups was there no C to offer sacrifice to God on behalf of the common ground? people A Sadducees and Romans B Publicans and Zealots Which of the following is not used to mean the C Sadducees and Pharisees first five books of the Bible? A Law of Moses Which of the following groups was most B Talmud violently opposed to Roman rule? C Torah A Zealots D Pentateuch B Pharisees C Publicans 2 Write each group with a description that best fits. Zealots Conquerors In each case give a one-sentence reason for your Samaritans Collaborators answer. -

Honigmanonigman - 9780520275584.Indd9780520275584.Indd 1 228/06/148/06/14 2:382:38 PMPM 2 General Introduction

General Introduction SUMMARY Th e fi rst and second books of Maccabees narrate events that occurred in Judea from the 170s through the 150s and eventually led to the rise of the Hasmonean dynasty: the toppling of the last high priest of the Oniad dynasty, the transforma- tion of Jerusalem into a Greek polis, Antiochos IV’s storming of Jerusalem, his desecration of the temple and his so-called persecution of the Jews, the liberation of the city and rededication of the temple altar by Judas Maccabee, the foundation of the commemorative festival of Hanukkah, and the subsequent wars against Seleukid troops. 1 Maccabees covers the deeds of Mattathias, the ancestor of the Maccabean/Hasmonean family, and his three sons, Judas, Jonathan, and Simon, taking its story down to the establishment of the dynastic transmission of power within the Hasmonean family when John, Simon’s son, succeeded his father; whereas 2 Maccabees, which starts from Heliodoros’s visit to Jerusalem under the high priest Onias III, focuses on Judas and the temple rededication, further dis- playing a pointed interest in the role of martyrs alongside that of Judas. Because of this diff erence in chronological scope and emphasis, it is usually considered that 1 Maccabees is a dynastic chronicle written by a court historian, whereas 2 Macca- bees is the work of a pious author whose attitude toward the Hasmoneans has been diversely appreciated—from mild support, through indiff erence, to hostility. Moreover, the place of redaction of 2 Maccabees, either Jerusalem or Alexandria, is debated. Both because of its comparatively fl amboyant style and the author’s alleged primarily religious concerns, 2 Maccabees is held as an unreliable source of evidence about the causes of the Judean revolt. -

Print Friendly Version

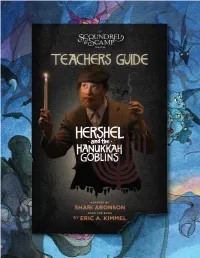

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 The Holiday of Hanukkah 5 Judaism and the Jewish Diaspora 8 Ashkenazi Jews and Yiddish 9 Latkes! 10 Pickles! 11 Body Mapping 12 Becoming the Light 13 The Nigun 14 Reflections with Playwright Shari Aronson 15 Interview with Author Eric Kimmel 17 Glossary 18 Bibliography Using the Guide Welcome, Teachers! This guide is intended as a supplement to the Scoundrel and Scamp’s production of Hershel & The Hanukkah Goblins. Please note that words bolded in the guide are vocabulary that are listed and defined at the end of the guide. 2 Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins Teachers Guide | The Scoundrel & Scamp Theatre The Holiday of Hanukkah Introduction to Hanukkah Questions: In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah means inauguration, dedication, 1. What comes to your mind first or consecration. It is a less important Jewish holiday than others, when you think about Hanukkah? but has become popular over the years because of its proximity to Christmas which has influenced some aspects of the holiday. 2. Have you ever participated in a Hanukkah tells the story of a military victory and the miracle that Hanukkah celebration? What do happened more than 2,000 years ago in the province of Judea, you remember the most about it? now known as Palestine. At that time, Jews were forced to give up the study of the Torah, their holy book, under the threat of death 3. It is traditional on Hanukkah to as their synagogues were taken over and destroyed. A group of eat cheese and foods fried in oil. fighters resisted and defeated this army, cleaned and took back Do you eat cheese or fried foods? their synagogue, and re-lit the menorah (a ceremonial lamp) with If so, what are your favorite kinds? oil that should have only lasted for one night but that lasted for eight nights instead. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020 (3 credits; MW 10:05-11:25; Oegema; Zoom & Recorded) Instructor: Prof. Dr. Gerbern S. Oegema Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University 3520 University Street Office hours: by appointment Tel. 398-4126 Fax 398-6665 Email: [email protected] Prerequisite: This course presupposes some basic knowledge typically but not exclusively acquired in any of the introductory courses in Hebrew Bible (The Religion of Ancient Israel; Literature of Ancient Israel 1 or 2; The Bible and Western Culture), New Testament (Jesus of Nazareth, New Testament Studies 1 or 2) or Rabbinic Judaism. Contents: The course is meant for undergraduates, who want to learn more about the history of Ancient Judaism, which roughly dates from 300 BCE to 200 CE. In this period, which is characterized by a growing Greek and Roman influence on the Jewish culture in Palestine and in the Diaspora, the canon of the Hebrew Bible came to a close, the Biblical books were translated into Greek, the Jewish people lost their national independence, and, most important, two new religions came into being: Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. In the course, which is divided into three modules of each four weeks, we will learn more about the main historical events and the political parties (Hasmonaeans, Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.), the religious and philosophical concepts of the period (Torah, Ethics, Freedom, Political Ideals, Messianic Kingdom, Afterlife, etc.), and the various Torah interpretations of the time. A basic knowledge of this period is therefore essential for a deeper understanding of the formation of the two new religions, Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, and for a better understanding of the growing importance, history and Biblical interpretation have had for Ancient Judaism. -

The Physician in Ancient Israel: His Status and Function

Medical History, 2001, 45: 377-394 The Physician in Ancient Israel: His Status and Function NIGEL ALLAN* For centuries the Jews have distinguished themselves in the practice of medicine, a tradition reaching back to Talmudic times when rabbis were frequently ac- knowledged for their healing skills.' This trend developed during the medieval period in Europe, when Jews, excluded from practically all the learned professions, turned to medicine as a means of livelihood.2 As a result, the Jews have been esteemed for their medical skills and, in our own time, continue to occupy a distinguished position in the medical profession throughout the world.3 Yet the honoured place occupied by the physician in Jewish society was not inherent to ancient Israel, but evolved through the centuries in ever changing circumstances. This article traces the development of the role of the physician in ancient Israel down to the close of the second Temple period in AD 70. It draws upon biblical pseudepigraphal and apocryphal literature, also referring to other sources when relevant to the subject (e.g. Josephus, Philo, the Talmud, etc.). The linguistic aspects of the root rf' in the Hebrew Scriptures are examined before the paper moves into the post-exilic period in which the development of the concept of the professional healer is traced down to the first description of the physician in Jewish literature by Shim'on b. Jeshua' b. Sira, known in Christian and Greek literature as Jesus ben Sirach, during the second century BC. In biblical times sickness and death were interpreted as God's punishment for dis- obedience to his will. -

Good News & Information Sites

Written Testimony of Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) National President Morton A. Klein1 Hearing on: A NEW HORIZON IN U.S.-ISRAEL RELATIONS: FROM AN AMERICAN EMBASSY IN JERUSALEM TO POTENTIAL RECOGNITION OF ISRAELI SOVEREIGNTY OVER THE GOLAN HEIGHTS Before the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Subcommittee on National Security Tuesday July 17, 2018, 10:00 a.m. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2154 Chairman Ron DeSantis (R-FL) Ranking Member Stephen Lynch (D-MA) Introduction & Summary Chairman DeSantis, Vice Chairman Russell, Ranking Member Lynch, and Members of the Committee: Thank you for holding this hearing to discuss the potential for American recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, in furtherance of U.S. national security interests. Israeli sovereignty over the western two-thirds of the Golan Heights is a key bulwark against radical regimes and affiliates that threaten the security and stability of the United States, Israel, the entire Middle East region, and beyond. The Golan Heights consists of strategically-located high ground, that provides Israel with an irreplaceable ability to monitor and take counter-measures against growing threats at and near the Syrian-Israel border. These growing threats include the extremely dangerous hegemonic expansion of the Iranian-Syrian-North Korean axis; and the presence in Syria, close to the Israeli border, of: Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Quds forces; thousands of Iranian-armed Hezbollah fighters; Palestinian Islamic Jihad (another Iranian proxy); Syrian forces; and radical Sunni Islamist groups including the al Nusra Levantine Conquest Front (an incarnation of al Qaeda) and ISIS. The Iranian regime is attempting to build an 800-mile land bridge to the Mediterranean, running through Iraq and Syria. -

Chanukah Activity Pack 2020

TTHHEE GGRREEAATT SSYYNNAAGGOOGGUUEE CCHHAANNUUKKAAHH ActivityActivity PackPack 22002200 -- 55778811 T H E S T O R Y O F C H A N U K A H A long, long time ago in the land of Israel, the most special place for the Jewish people was the Temple in Jerusalem. The Temple contained many beautiful objects, including a tall, golden menorah. Unlike menorahs of today, this one had seven (rather than nine) branches. Instead of being lit by candles or light bulbs, this menorah burned oil. Every evening, oil would be poured into the cups that sat on top of the menorah. The Temple would be filled with shimmering light. At the time of the Hanukkah story, a mean king named Antiochus ruled over the land of Israel. “I don’t like these Jewish people,” declared Antiochus. “They are so different from me. I don’t celebrate Shabbat or read from the Torah, so why should they?” Antiochus made many new, cruel rules. “No more celebrating Shabbat! No more going to the Temple, and no more Torah!” shouted Antiochus. He told his guards to go into the Temple and make a mess. They brought mud, stones, and garbage into the Temple. They broke furniture and knocked things down; they smashed the jars of oil that were used to light the menorah. Antiochus and his soldiers made the Jews feel sad and angry. A Jewish man named Judah Maccabee said, “We must stop Antiochus! We must think of ways to make him leave the land of Israel.” At first, Judah’s followers, called the Maccabees, were afraid. -

1 Maccabees, Chapter 1

USCCB > Bible 1 MACCABEES, CHAPTER 1 From Alexander to Antiochus. 1 a After Alexander the Macedonian, Philip’s son, who came from the land of Kittim,* had defeated Darius, king of the Persians and Medes, he became king in his place, having first ruled in Greece. 2 He fought many battles, captured fortresses, and put the kings of the earth to death. 3 He advanced to the ends of the earth, gathering plunder from many nations; the earth fell silent before him, and his heart became proud and arrogant. 4 He collected a very strong army and won dominion over provinces, nations, and rulers, and they paid him tribute. 5 But after all this he took to his bed, realizing that he was going to die. 6 So he summoned his noblest officers, who had been brought up with him from his youth, and divided his kingdom among them while he was still alive. 7 Alexander had reigned twelve years* when he died. 8 So his officers took over his kingdom, each in his own territory, 9 and after his death they all put on diadems,* and so did their sons after them for many years, multiplying evils on the earth. 10 There sprang from these a sinful offshoot, Antiochus Epiphanes, son of King Antiochus, once a hostage at Rome. He became king in the one hundred and thirty-seventh year* of the kingdom of the Greeks. Lawless Jews. 11 b In those days there appeared in Israel transgressors of the law who seduced many, saying: “Let us go and make a covenant with the Gentiles all around us; since we separated from them, many evils have come upon us.” 12 The proposal was agreeable; 13 some from among the people promptly went to the king, and he authorized them to introduce the ordinances of the Gentiles. -

Revolutionaries in the First Century

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 9 7-1-1996 Revolutionaries in the First Century Kent P. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Kent P. (1996) "Revolutionaries in the First Century," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jackson: Revolutionaries in the First Century masada and life in first centuryjudea Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1996 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 36, Iss. 3 [1996], Art. 9 revolutionaries in the first century kent P jackson zealotszealousZealots terrorists freedom fighters bandits revolutionaries who were those people whose zeal for religion for power or for freedom motivated them to take on the roman empire the great- est force in the ancient world and believe that they could win because the books ofofflaviusjosephusflavius josephus are the only source for most of our understanding of the participants in the first jewish revolt we are necessarily dependent on josephus for the answers to this question 1 his writings will be our guide as we examine the groups and individuals involved in the jewish rebellion I21 in -

Who Were the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes & Zealots

Who were the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes & Zealots The Sadducees were mostly members of the wealthy conservative elite. They had opened their hearts to the secular world of Greek culture and commerce, while insisting that the only worthy form of Judaism was to be found in a rather spiritless, fundamentalist, “pure letter-of-the-law” reading of the Torah. Philosophically, they denied such concepts as resurrection, personal immortality, or other ideas that were only found in the Oral tradition (eventually written down in the Talmud). Politically, they contented themselves with the way things were and resisted change – preferring instead to promote cordial relations with the Romans. Although they often held influential positions in society, they were unpopular with the masses who generally opposed all foreign influences. The Pharisees, the largest group, were mostly middle-class Jews who emphasized the exact keeping of the law as it had been interpreted by sages, elders, and rabbis. Politically, they were ardent anti-Hellenists and anti-Romans. The Pharisees were admired by the majority of Jews, but they were never a very large group since most people had neither the education nor the time to join the party and follow all their stringent rules regarding prayer, fasting, festival observance, tithing, etc. Pharisees were greatly influenced by Persian ideas of Good and Evil, and they adhered to the growing belief in the resurrection of the body with an afterlife of rewards and punishments. Over time, many of the finer impulses of Pharisaism would weaken into an empty religious formalism (as is ever the case), focusing on outward actions rather than the inward experience of the soul. -

Plotting Antiochus's Persecution

JBL123/2 (2004) 219-234 PLOTTING ANTIOCHUS'S PERSECUTION STEVEN WEITZMAN [email protected] Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405-7005 The history of religious persecution could be said to have begun in 167 B.C.E. when the Seleucid king Antiochus IV issued a series of decrees outlawing Jewish religious practice. According to 1 Maccabees, anyone found with a copy of the Torah or adhering to its laws—observing the Sabbath, for instance, or practicing circumcision—was put to death. Jews were compelled to build altars and shrines to idols and to sacrifice pigs and other unclean animals. The temple itself was desecrated by a "desolating abomination" built atop the altar of burnt offering. The alternative account in 2 Maccabees adds to the list of outrages: the temple was renamed for Olympian Zeus, and the Jews were made to walk in a procession honoring the god Dionysus. Without apparent precedent, the king decided to abolish an entire religion, suppressing its rites, flaunting its taboos, forcing the Jews to follow "customs strange to the land." Antiochus IV s persecution of Jewish religious tradition is a notorious puz zle, which the great scholar of the period Elias Bickerman once described as "the basic and sole enigma in the history of Seleucid Jerusalem."1 Earlier for eign rulers of the Jews in Jerusalem, including Antiochus s own Seleucid fore bears, were not merely tolerant of the religious traditions of their subjects; they often invested their own resources to promote those traditions.2 According to Josephus, Antiochus III, whose defeat of the Ptolemaic kingdom at the battle of Panium in 200 B.C.E.