Christel Braae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2005 — Vol

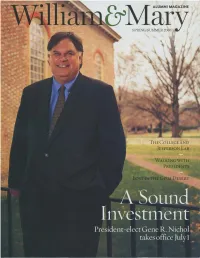

W&M CONTENTS SPRING/SUMMER 2005 — VOL. 70, NO. 3/4 FEATURES William and Mary English Professor Henry Hart traveled 34 AT WILLIAM AND MARY, 40 through Northern China to research the life of his mis- THE NICHOL IS STRONG sionary great-grandfather. Introducing the College’s 26th President BY MELISSA V. PINARD 38 FROM GRAPE TO GLASS Childhood Roots Make for Robust Wine Label BY DANIELLA J. GROSSMAN ’06 40 LOST IN THE GOBI DESERT A Professor’s Journey Through Northern China BY HENRY W. HART 46 WALKING WITH PRESIDENTS The Story of Secret Service Agent John Pforr ’60 BY SANDRA K. JACKSON ’05 50 ACCELERATING W&M’s Relationship with Jefferson Lab BY SYLVIA CORNELIUSSEN DEPARTMENTS 5 PUBLISHER’S NOTE 32 PHILANTHROPY 17 6 MAILBOX 61 CLASS NOTES 9 AROUND THE WREN 112 VITAL STATISTICS 15 VIEWPOINT 126 WHO, WHAT, WHERE 17 ALUMNI SPIRIT 128 CIRCA 22 JUST OFF DOG STREET Karen R. Cottrell ’66, M.Ed. ’69, Ed.D. ’84 has been named executive vice president 25 ARTS & HUMANITIES ON THE COVER: President-elect Gene R. Nichol of the Alumni Association. stands on the Wren portico. TOP PHOTO: AXEL ODELBERG; BOTTOM PHOTO: CHRIS SMITH/PHOTOGRAPHY TOP PHOTO: AXEL ODELBERG; 29 TRIBE SPORTS PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS SMITH/PHOTOGRAPHY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING/SUMMER 2005 3 PUBLISHER’SNOTE SPRING/SUMMER 2005 VOLUME 70, NUMBER 3/4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Walter W. Stout ’64, President Proud Past, Henry H. George ’65, Vice President Marilyn Ward Midyette ’75, Treasurer Russell E. Brown Jr. ’74, Secretary James E. Ukrop ’60, L.H.D. -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

L'alta Asia Buddhista (Tibet, Bhutan E Mongolia)

Università di Pisa Scuola di Dottorato in Scienze Politiche e Sociali Corso in Geopolitica L’Alta Asia buddhista (Tibet, Bhutan e Mongolia) tra il crepuscolo dell’Impero Ch’ing e la nascita della Repubblica cinese: aspetti geopolitici e diplomatici britannici Settore scientifico disciplinare: SPS/14 Storia e istituzioni dell’Asia Dottorando: Matteo Miele Tutor: Chiar.mo Prof. Maurizio Vernassa 2014 A mio fratello Alessandro, a Namkha, come un fratello e ai miei studenti in Bhutan 2 Gairīshchā afshtachinō yazamaide We praise the mountains from which the waters flow Haftan Yasht, Kardāh VIII (Khordeh Avestā, The Trustees of the Parsi Panchayat Funds and Properties, Bombay, 1993) 3 Sommario Ringraziamenti 7 Traslitterazione e trascrizione dei termini in lingue asiatiche 9 Date 10 Nota sui documenti d’archivio 10 Abbreviazioni 11 Introduzione 12 PROLOGO: IL DHARMA E IL RE 15 Capitolo 1 – Lo spazio politico del buddhismo tibetano: la dimensione religiosa del legame tra Tibet, Bhutan e Mongolia 16 Il buddhismo tibetano 21 Il Dalai Lama 23 PRIMA PARTE: L’AGONIA DELL’IMPERO 31 Capitolo 2 – Il Tibet alla fine del Grande gioco 32 La spedizione russa del 1899-1901 32 Un incontro 34 Alla fine del Grande gioco: Younghusband a Lhasa 37 Antiche paure 45 L’Accordo 53 Capitolo 3 – I Ch’ing, il Dalai Lama e gli inglesi (1906-1908) 57 La “Nuova Politica” in Tibet 62 Il Dalai Lama a Pechino (settembre-dicembre 1908) 63 Il Dalai Lama di nuovo a Lhasa 71 Capitolo 4 – Tra i due imperi: il Regno del Bhutan 73 Una premessa d’attualità geopolitica 74 Il nuovo Bhutan ed il Trattato di Punakha 77 Il Dalai Lama in India 84 4 Spie e minacce cinesi sul Bhutan 89 Il tributo mai pagato: il Nepal e la Cina 98 La Repubblica cinese 114 SECONDA PARTE: LA REPUBBLICA E IL FANTASMA MANCESE 118 Capitolo 5 – L’indipendenza tibetana 119 L’anno bufalo-acqua. -

European Elites and Ideas of Empire, 1917–1957

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.22, on 02 Oct 2021 at 05:04:48, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/DC85C5D84467A2F4A8F8E5EE7BD2B4AA Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.22, on 02 Oct 2021 at 05:04:48, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/DC85C5D84467A2F4A8F8E5EE7BD2B4AA EUROPEAN ELITES AND IDEAS OF EMPIRE, 1917–1957 Who thought of Europe as a community before its economic integra- tion in 1957? Dina Gusejnova illustrates how a supranational European mentality was forged from depleted imperial identities. In the revolutions of 1917–1920, the power of the Hohenzollern, Habsburg, and Romanoff dynasties over their subjects expired. Even though Germany lost its credit as a world power twice in that century, in the global cultural memory, the old Germanic families remained associated with the idea of Europe in areas reaching from Mexico to the Baltic region and India. Gusejnova’s book sheds light on a group of German-speaking intellectuals of aristocratic origin who became pioneers of Europe’s future regeneration. In the minds of transnational elites, the continent’s future horizons retained the con- tours of phantom empires. This title is available as Open Access at 10.1017/9781316343050. dina gusejnova is Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Sheffield. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.22, on 02 Oct 2021 at 05:04:48, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

Mongolian Studies in the Nordic Countries : a Brief Historical Survey

Title Mongolian Studies in the Nordic Countries : A Brief Historical Survey Author(s) JANHUNEN, Juha Citation 北方人文研究, 5, 43-55 Issue Date 2012-03-31 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/49269 Type bulletin (article) Note Special Contribution File Information 04journal05-janhuen.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP 〈Special Contribution〉 Mongolian Studies in the Nordic Countries: A Brief Historical Survey Juha JANHUNEN Helsinki University The Nordic countries form a region of five relatively small and sparsely inhabited kingdoms and republics in Northern Europe: Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland. In spite of their small populations, these countries have made considerable contributions to the exploration of the rest of the world. Sweden and Norway, in particular, but also Denmark with its possession of Greenland, have been active exploring the Arctic and Antarctic regions, but in addition to this line of research there is a great tradition of Asian studies, which also comprises Finland. Among the geographical targets of Finnish and Scandinavian scholars in Asia, Mongolia has always occupied an important place. However, to some extent, the field of Mongolian studies in the different Nordic countries has had different backgrounds and motives. Particularly conspicuous differences exist between Finland, on the one hand, and the Scandinavian countries, on the other. The present paper summarizes the history of the field and highlights some of the results achieved.* The Beginnings of Mongolian studies in Finland Among the Nordic countries, Finland has the longest and broadest tradition in Mongolian studies. This is due to two circumstances: First, between 1809 and 1917 Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy under the Russian Empire, and Finnish scholars were freely able to travel in the eastern parts of Russia and from there enter also Mongolia. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Section A GENERAL WORKS Chapter 1 COLLECTIONS Inteimational Congress of Orientalists (ICO) l4th Aotes du XlVe Congres International des Orientalistes3 Alger, 1905 . Part I, section 5- Paris: Ernest Leroux, I906. 22 nd 'Proceedings of the Twenty-second International Congress of Orientalists held in Istanbul^ September 15th to 22nd 1951. Vol. 2 : Communications. Edited by Zeki Velidi Togan. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1957. 65O pp. 23rd Proceedings of the Twenty-third International Congress of Orientalists3 Cambridge3 21st-28th August3 1954. Edited by Denis Sinor. London: Royal Asiatic Society, 195^. ^21 pp, 24th Akten des vierundzwanzigsten Intenuxtionalen Orientalisten-Kongresses Munchen3 28. August bis 4. September 1957. Edited by Herbert Franke. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner, 1959. TT6 pp, 25th Trudy 25. Mezhdunarodnogo Kongressa Vostokovedov. Moscow: Izdatel'stvo Vostochnoi Literatiary, 1963. Vol. 3, section 11: Altaistika, pp. 234- 442; Vol, 5, section 18: Istoriya mongolii3 PP* 302-354. 26th Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth International Congress of Orientalists3 New Delhi3 4^l0th Januax^3 1964. New Delhi. Vol. 2 (1968), section 4: Altaic Studies3 pp. 83-180. 27th Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh International Congress of Orientalists3 Ann Arbor3 Michigan3 13th-19th August 1967. Edited by Denis Sinor. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1971. 705 pp. Permanent International Altaistic Conference (PIAC) 5th Aspects of Altaic Civilization: Proceedings of the Fifth Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference held at Indiana University3 June 4-63 1962. Edited by Denis Sinor. Bloomington, Indiana, I963. 263 pp. (Uralic and Altaic Series, v, 23.) 6th Sitzungsberichte der 6. Arbeitstagung der Permanent International Altaistic Conference in Eelsinki3 4^8.6.1963. (= Journal de la Societe Finno-Ougrienne 65 C19651.) 7th Proceedings of the Seventh Meeting of the Permanent International 1 chapter 1 Altaistia Conference^ 23 Augustus - 3 September 1964. -

Mongolia and the United States a Diplomatic History

Mongolia and the United States A Diplomatic History Jonathan S. Addleton An ADST-DACOR Diplomats and Diplomacy Book Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Jonathan S. Addleton 2013 Th e views and opinions in this book are solely those of the author and not necessarily those of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, DACOR, or the Government of the United States. ISBN 978-988-8139-94-1 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitt ed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co. Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Acronyms vii Glossary of Mongolian Terms ix Introduction xi Chapter 1: Early Encounters 1 Chapter 2: Establishing Diplomatic Relations 17 Chapter 3: Supporting Democracy 37 Chapter 4: Partnering on Development 61 Chapter 5: Building Commercial Ties 87 Chapter 6: Promoting Security 101 Chapter 7: Sustaining People-to-People Relationships 117 Chapter 8: Looking Ahead 141 Annexes Key Agreements between the United States and Mongolia, 1987–2012 153 US Ambassadors and Heads of Agencies in Mongolia, 1987–2012 155 US-Mongolia Joint Statement Issued at the White House, June 16, 2011 157 US Senate Resolution on Mongolia, Sponsored by Senators Kerry, 161 McCain, Murkowski, and Webb, June 17, 2011 vi Contents Major Sources and Further Reading 165 Acknowledgments 171 Index 175 About the Author 187 Introduction On January 27, 1987, senior diplomats from the United States and Mongolia met in a modest ceremony below a portrait of Th omas Jeff erson in the Treaty Room of the Department o f State in Washington, D.C. -

European Elites and Ideas of Empire, 1917…1957

EUROPEAN ELITES AND IDEAS OF EMPIRE, 1917–1957 Who thought of Europe as a community before its economic integra- tion in 1957? Dina Gusejnova illustrates how a supranational European mentality was forged from depleted imperial identities. In the revolutions of 1917–1920, the power of the Hohenzollern, Habsburg, and Romanoff dynasties over their subjects expired. Even though Germany lost its credit as a world power twice in that century, in the global cultural memory, the old Germanic families remained associated with the idea of Europe in areas reaching from Mexico to the Baltic region and India. Gusejnova’s book sheds light on a group of German-speaking intellectuals of aristocratic origin who became pioneers of Europe’s future regeneration. In the minds of transnational elites, the continent’s future horizons retained the con- tours of phantom empires. This title is available as Open Access at 10.1017/9781316343050. dina gusejnova is Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Sheffield. new studies in european history Edited by peter baldwin, University of California, Los Angeles christopher clark, University of Cambridge james b. collins, Georgetown University mia rodriguez-salgado, London School of Economics and Political Science lyndal roper, University of Oxford timothy snyder, Yale University The aim of this series in early modern and modern European history is to publish outstanding works of research, addressed to important themes across a wide geographical range, from southern and central Europe, to Scandinavia and Russia, from the time of the Renaissance to the present. As it develops, the series will comprise focused works of wide contextual range and intellectual ambition. -

Box/Folder List

Container Contents 1 Container Contents 1 Early Family Papers, 1860-1910 & undated Hall, Anna:1883-1891 & undated Hall, Valentine G.,Jr.: 1875-1876 Hall, Mrs. Valentine G.,Jr.: 1860-1896 & undated Morgan, Edith Hall: Writings of Mrs. W. Forbes Morgan Parish, Susan: 1880-1910 Roosevelt, Elliott: 1868-1895 & undated Roosevelt, Elliott: Writings Flyleaves from Roosevelt Family Books: 1871-1893 Family & Personal Correspondence, 1894-1957 & undated A-C Business Matters 2 Condolence Letters After FDR’s Polio Attack Letters to ER Letters to FDR D-F Engagement Congratulations: 1904-1905 Letters to ER Letters to FDR G-K Gray, David & Maude Hall, Edward Ludlow Invitations: 1902-1932 L-P Letters in French Longworth, Alice Roosevelt 3 Poetry Selections “Prinzessin Victoria Luise” R-Z Roosevelt, A-W Roosevelt, Betsy Cushing (Mrs.James) Roosevelt, Elliott: 1942-45 & 1954-57 Roosevelt, Elliott: Virginia Property Roosevelt, Franklin D. Bok Peace Award: “A Plan to Preserve World Peace” Letters to ER:1908-20 Miscellaneous Letters & Papers: 1894-1932 & undated Roosevelt, Franklin D. Jr.: 1923-1949 & undated Roosevelt, G. Hall “Roosevelts in Virginia” Goodridge Wilson Family & Personal Correspondence: 1894-1957 & undated Souvestre, Marie School Exercise Books & Notebooks: c. 1892-1902 Journal & Composition Books Latin Exercises Grammar Notebook Allenswood Container Contents Container Contents 2 4 School Exeercise Books & Notebooks: c.1892-1902 English Literature Notebook French Notebooks French Literature I Notebook, Summer 1901 French Literture II Notebook, -

Report Title 11. Jahrhundert

Report Title - p. 1 Report Title 11. Jahrhundert 1024 Religion : Christentum Porter, Lucius Chapin. China's challenge to Christianity. (New York, N.Y. : Missionary Education Movement of the United States and Canada, 1924). https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001400916. [WC] 13. Jahrhundert 1295 Religion : Christentum Jahballaha III., der Katholikos der Nestorianer, kann durch seine Beziehungen zu den mongolischen Herrschern die Ausbreitung der nestorianischen Kirche erreichen und die Unterdrückung der Christen mildern. [BBKL] 1299 Religion : Christentum Giovanni da Montecorvino baut die erste Kirche in Beijing. [Wik] 14. Jahrhundert 1304 Religion : Christentum Jahballaha III. sendet ein Glaubensbekenntnis an Benedikt XI., in dem er den Primat des Papstes anerkennt. [BBKL] 1305 Religion : Christentum Giovanni da Montecorvino baut die zweite Kirche in Beijing. [Wik] 1307 Religion : Christentum Errichtung der Erzdiözese Beijing mit sieben Suffraganten (ein zu einer Kirchenprovinz gehörendes Bistum). Giovanni da Montecorvino wird Erzbischof. [Wal,Col] 1307 Religion : Christentum Andrea da Perugia wird von Papst Clemens V. nach China geschickt. [Wik] 1313 Religion : Christentum Errichtung der Diözese Zaitun (Quanzhou, Fujian). [Wal 1] 1322-1332 Religion : Christentum Andrea da Perugia ist Bischof von Quanzhou (Fujian). [Wik,BG11:S. 40] 1325-1328 Religion : Christentum Odorico da Pordenone ist in Beijing als Mitarbeiter von Giovanni da Montecorvino tätig. [BBKL] 1328 Religion : Christentum Es gibt ca. 30'000 Katholiken in China. [Col] 1333 Geschichte : China - Europa : Island / Religion : Christentum Nicolas de Botras wird Nachfolger von Giovanni da Montecorvino als Bischof von Qanbaliq (Beijing). [Sta] Report Title - p. 2 1342 Religion : Christentum Die Franziskaner Giovanni da Marignolli und Nicholas Bonet kommen im Auftrag von Papst Benedikt XII.. in Khanbaliq (Beijing) an und werden von Kaiser Shundi ehrenvoll empfangen. -

Mongolian Studies in the Nordic Countries : a Brief Historical Survey

Title Mongolian Studies in the Nordic Countries : A Brief Historical Survey Author(s) JANHUNEN, Juha Citation 北方人文研究, 5, 43-55 Issue Date 2012-03-31 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/49269 Type bulletin (article) Note Special Contribution File Information 04journal05-janhuen.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP 〈Special Contribution〉 Mongolian Studies in the Nordic Countries: A Brief Historical Survey Juha JANHUNEN Helsinki University The Nordic countries form a region of five relatively small and sparsely inhabited kingdoms and republics in Northern Europe: Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland. In spite of their small populations, these countries have made considerable contributions to the exploration of the rest of the world. Sweden and Norway, in particular, but also Denmark with its possession of Greenland, have been active exploring the Arctic and Antarctic regions, but in addition to this line of research there is a great tradition of Asian studies, which also comprises Finland. Among the geographical targets of Finnish and Scandinavian scholars in Asia, Mongolia has always occupied an important place. However, to some extent, the field of Mongolian studies in the different Nordic countries has had different backgrounds and motives. Particularly conspicuous differences exist between Finland, on the one hand, and the Scandinavian countries, on the other. The present paper summarizes the history of the field and highlights some of the results achieved.* The Beginnings of Mongolian studies in Finland Among the Nordic countries, Finland has the longest and broadest tradition in Mongolian studies. This is due to two circumstances: First, between 1809 and 1917 Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy under the Russian Empire, and Finnish scholars were freely able to travel in the eastern parts of Russia and from there enter also Mongolia. -

Spring Series of Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art

PRESS RELEASE | HONG KONG | 16 April 2019 SPRING SERIES OF CHINESE CERAMICS AND WORKS OF ART SALES Glories of Buddhist Art The Baofang Pavilion Collection of Imperial Ceramics Four Masterpieces of Jun Ware Leisurely Delights of a Transient Life Important Chinese Ceramics and Works Of Art A Selection of Highlights to be auctioned on 29 May From left to right: A HIGHLY IMPORTANT MAJESTIC PAIR OF WOOD FIGURES OF STANDING BODHISATTVAS THE LARSON YONGZHENG VASE A HIGHLY IMPORTANT IMPERIAL WHITE JADE 'ZHOUJIA YANXI ZHI BAO' SEAL Christie’s Hong Kong Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art auctions will take place on 29 May with five dedicated themed auctions featuring the Glories of Buddhist Art and the return of the well-established Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art sales as well as the second edition of the Leisurely Delights of A Transient Life sale. Chi Fan Tsang, Deputy Chairman, Specialist Head of Department, commented, “This season celebrates our most popular sales, most notably the Buddhist themed sale which continues to captivate collectors. The five specially curated auctions present a breadth and depth of the finest works on the market and cater to the discerning and diverse tastes of our clients”. GLORIES OF BUDDHIST ART This special-themed sale includes several masterpieces of Buddhist art of superb quality and impeccable provenance, which have rarely been seen on the market for many decades. Leading the sale is a pair of highly important and majestic wood figures of the bodhisattvas Guanyin and Mahasthamaprapta, dating to the Five Dynasties to early Northern Song period (AD 10th-11th century).