Christian Missionaries in Mongolia After 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of a Local Catholic Church Through Cross-Cultural Encounters in the Ordos Region (Inner Mongolia)

Patrick Taveirne, “The Rise of a Local Catholic Church Through Cross Cultural Encounters in Ordos Region (Inner Mongolia)” The Rise of a Local Catholic Church Through Cross-Cultural Encounters in The Ordos Region (Inner Mongolia) Patrick M.W. Taveirne [Abstract] Because of the limitations of historical, geographical, human and material resources, most of the important academic activities and accomplished scholarship are concentrated in major metropolitan universities and academies in Beijing, Shanghai, or other major cities. Archival materials and research resources are thus closely related to these locales. Yet the presence and development of Christianity and in particular the Catholic Church in China was not confined to these places. This article, by way of a case study, will explore the historical development of a small Mongol Catholic community at China’s northern periphery from the Late Qing Dynasty until the Republican Era. It will focus on the available multicultural archival materials, the relevance and limitations of these resources regarding the writing of “A History of the Catholic Church in China.” - 53 - 《天主教研究學報》〈中國天主教教會史學:歷史資源和方法論〉 第十期 2019 年 The second half of the 19th century saw the conjuncture of two unprecedented trends of expansion: that of sedentary Han Chinese pushing forward the frontier of settlement into Inner Mongolia and Manchuria, and that of Western powers forcing their way into China through gunboats and unequal treaties. At the forefront of the Western expansion were Catholic and Protestant missionaries. The Sino-French Convention of Beijing in 1860 allowed the missionaries to penetrate into not only the Chinese interior or eighteen provinces of China proper, but also the Mongolian territory outside the Great Wall 塞外, where they rented or leased land, and constructed churches, on behalf of the local Christian community. -

Judicial Reform: Strengthening Access to Justice by the Disadvantaged

SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME PHI/02/007 – JUDICIAL REFORM: STRENGTHENING ACCESS TO JUSTICE BY THE DISADVANTAGED THE OTHER PILLARS OF JUSTICE THROUGH REFORMS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE DIAGNOSTIC REPORT JUNE 2003 CENTER FOR PUBLIC RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, INC. Consultants, inc PHI/02/007 – JUDICIAL REFORM: STRENGTHENING ACCESS TO JUSTICE BY THE DISADVANTAGED STRENGTHENING THE OTHER PILLARS OF JUSTICE THROUGH REFORMS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE DIAGNOSTIC REPORT JUNE 2003 Government of the Philippines • United Nations Development Programme PHI/02/007 – Judicial Reform : Strengthening Access to Justice by the Disadvantaged Strengthening the Other Pillars of Justice through Reforms in the Department of Justice (DOJ) DIAGNOSTIC REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Chapter 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 Background of the TA 1-1 2 Project Objectives 1-2 3 Project Scope 1-2 4 Outputs of the TA 1-3 5 Organization of Report 1-3 Chapter 2 RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 1 Introduction 2-1 2 Institutional Framework 2-6 3 Assessment Approach 2-8 Chapter 3 LAW ENFORCEMENT 1 Introduction 3-1 2 Institutional Framework 3-1 3 Overview of Key Operations and Performance 3-4 4 SWOT Analysis 3-15 5 Internal Capacity Assessment 3-22 6 Implications for Reforms 3-46 Chapter 4 PROSECUTION PILLAR 1 Introduction 4-1 2 Institutional Framework 4-1 3 Overview of Key Operations and Performance 4-4 4 SWOT Analysis 4-20 5 Internal Capacity Assessment 4-26 6 Implications for Reforms 4-40 Chapter 5 CORRECTIONS PILLAR 1 Introduction 5-1 2 Institutional Framework 5-1 3 Bureau of Corrections 5-6 4 Parole and Probation Administration 5-31 5 Board of Pardons and Parole 5-47 Chapter 6 LEGAL ASSISTANCE 1 Introduction 6-1 2 Institutional Framework 6-1 3 Overview of Key Operations and Performance 6-8 4 SWOT Analysis 6-22 5 Internal Capacity Assessment 6-27 6 Implications for Reforms 6-33 Center for Public Resource Management, Inc. -

FINAL PROSPECTUS Ekklesia Mutual Fund 19/F, BPI Buendia Center, Sen

FINAL PROSPECTUS Ekklesia Mutual Fund 19/F, BPI Buendia Center, Sen. Gil J. Puyat Ave., Makati City 1209 Tel No. (02) 580-3566 / 580-3569 (An open-end investment company organized under Philippine Laws) An Offer of up to the Number of Authorized Shares of Ekklesia Mutual Fund at an Offer Price of Net Asset Value per Share on the date of subscription EKKLESIA MUTUAL FUND Number of Authorized Shares 245,000,000 Minimum Initial Investment PHP 5,000.00 PAR value PHP 1.00 Securities will be traded over the counter through SEC Certified Investment Solicitor (CISol) or via online facility BPI Investment Management, Inc. Fund Manager 19/F, BPI Buendia Center, Sen. Gil J. Puyat Ave., Makati City Tel No. (02) 580-3566 / 580-3569 BPI Investment Management, Inc., Tel No. (02) 580-3566 / 580-3569 19/F, BPI Buendia Center, Sen. Gil J. Puyat Ave., Makati City Principal Distributor The date of this PROSPECTUS is September 26, 2019. THESE SECURITIES SHALL BE SOLD AND REDEEMED ONLY THROUGH THE FUND’S DISTRIBUTORS. THE FUND’S SHARES SHALL NOT BE LISTED NOR TRADED ON THE PHILIPPINE STOCK EXCHANGE. SHARES OF THE FUND ARE NOT DEPOSITS OR OBLIGATIONS OF, OR GUARANTEED OR ENDORSED BY, ANY FINANCIAL INSTITUTION, AND ARE NOT INSURED WITH THE PHILIPPINE DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION. - 2 - EKKLESIA MUTUAL FUND, INC. SUMMARY OF FEES TO BE DEDUCTED FROM THE FUND Management, Distribution, Advisory and Transfer Agent Fee based on the average daily trading NAV of the Fund 1.75% p.a. Management Fee 0.85% p.a. Distribution Fee 0.85% p.a. -

One Goal, Two Methods Belgian and Dutch CICM Missionaries in Mongolia and Gansu During the Late Nineteenth Century

One Goal, two Methods Belgian and Dutch CICM missionaries in Mongolia and Gansu during the late nineteenth century Word count (excluding references): 25’508 Research Master Thesis: 30 ECTS Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Jos Gommans 25-12-2019 Thidrek Vossen (胡岺憧) ) Leiden University, s2095939 Motetpad 9, Nijmegen [email protected] - +31613932668 Inhoud Preface and acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Previous research ................................................................................................................................ 4 Method, sources and language ........................................................................................................... 8 Structure ............................................................................................................................................ 10 Ch. 1: The Historical and Spatial context of Scheut .............................................................................. 11 The Nineteenth Century Global Changes .......................................................................................... 11 The Chinese North-West: A Spatial consideration ............................................................................ 14 A Short Frontier History................................................................................................................ -

July-August 2020 Issue Vol. 56 No. 4 RP PROVINCE NEWSLETTER

RP PROVINCE NEWSLETTER July-August 2020 Issue Vol. 56 No. 4 His Holiness, Pope Francis, has just appointed our confrere FR FÉLICIEN NTAMBUE (CICM General Councilor) as Bishop of the Diocese of Kabinda, Democratic Republic of Congo. Let us thank the Lord for this appointment and pray for our confrere as he starts his new ministry in the Diocese of Kabinda. By Fr. Luke Moortgat, CICM Provincial Councillor PRELIMINARY NOTES: Privacy. To protect privacy I use fictitious names for people, sickness, etc. I also interchange gender related words like he, she, etc. I kept references for most important sources and I can give them to people who need them. Rounded Figures. While I love concrete numbers, I will often round off figures as long numbers are more difficult to remember. You also realize that data that are rounded off are not only easier to remember but in many cases also help practical understanding. As this article is not used as basis for more detailed studies but as a starting point for greater personal involvement, it is more than sufficient to have rounded figures. For many it is also easier to grasp and to use in a practical way a text stating that “worldwide one person out of 500 is infected” than “16,690,319 people out of a world population 8,099,141,505 are infected. Honest Reflection. When I ask “why” questions or others, it is often to help us to reflect. I do not worry that a reader forgets all the facts if he can just spend some time in solidly based honest reflection. -

Saint Mary's University

SAINT MARY’S UNIVERSITY 1. Contact Name of organization: Saint Mary’s University (Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya) Address of main office: Saint Mary's University College Campus , Bayombong Municipality, Province: Nueva Vizcaya 3700 , Philippines Website: http://www.smu.edu.ph/ Contact person: John Octavios Palina Phone number: 0063 78 321-2221 2. Organization Kind of organization: Education Institute/academic Short history: Saint Mary’s University traces its roots back to the dream and initiative of the late Msgr. Constant Jurgens, then Parish Priest of Bayombong and one of the earliest CICM missionaries to arrive in the Philippines. He wanted to establish a school to give the children of his parishioners the benefit of a Christian education. He purchased a lot and some materials for this purpose but then, he was recalled to Europe, thus, it was Rev. Fr. Achilles de Gryse, CICM, his successor, who saw his dream through. Thus, St. Mary’s Elementary School was inaugurated in June 1928. In 1934, with Fr. Godfrey Lambrecht, the High School was opened and in 1947, the College Department, offering A.A., B.S.E., A. B. and Jr. Normal course (ETC). Gradually, the course offerings expanded with Bachelor of Science in Commerce, (1951), Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering, (1955) and the Graduate School, (1962). Through the years, many more Departments, Colleges/Schools were opened with more degrees and title course offerings. To rise up to the challenge of maintaining quality education, the institution has submitted itself for accreditation by the PAASCU. Thus from its birth throes in 1928, Saint Mary's University has steadily grown over the years and has metamorphosed into one of the more developed and important institutions in the Philippines, particularly in the Cagayan Valley Region. -

Winter 2014 Priests in the Mission Rev

“Go, e efo e, make disciples of all io s ~ & B.W.I. (Mt. 28:19 ) Volume 15, Issue I Winter 2014 Priests in the Mission Rev. Luis Orlando González, Chancellor ROMAN CATHOLIC MISSION ‘SUI IURIS’ Turks and Caicos Islands; Pastor of Our Lady of Divine Providence Church, Providenciales Rev. Bruno Sammarco, Parochial Vicars, Our Lady of Divine Providence Church, Providenciales Rev. Rafael Velazquez Pastor of Church of the Holy Cross, Grand Turk Rev. Pedro Vilchez Parochial Vicar, Grand Turk Above: From the right Fr. Orlando the new Chancellor of the Roman Catholic Mission Sui Iuris, Turks and Caicos Islands, Governor His Excellency Peter Beckingham, Bishop Peter Baldacchino auxiliary bishop of Miami and Fr. Bruno Sammarco parochial vicar (left), feast of Our Lady of Divine Providence Church on Providenciales Island, November 16, 2014. Above: youth from the parish met once a month to share the Word of God, All students from Holy Family Academy participate of the liturgies this year 8 new missionaries teacher came to help the mission.. and feast of the parish, the third Sunday of November. Msgr. Rozniak, The Vicar General of the Missio Sui Iuris, visit us and share with us about the new play ground. Above: The Auxiliary bishop from Miami, His Excellence, Peter Baldacchino visits the Mission were 15 years of his life was given to bring this pastoral work accomplished by the Mission in such a short time. The first time that we celebrate Thanks given in Turk and Caicos Islands. Now is an official holiday. ROMAN MISSION, P.O. Box 340, Leeward Highway, Providenciales, TURKS & CAICOS ISLANDS, British West Indies; Phone / Fax: (649) 941-5136; E-mail: c i i @ c www.CATHOLIC.tc Volume 15, Issue I O N H O C O N N W R Page 2 A SCHOLARSHIP FUND is in place at HOLY FAMILY ACADEMY Catholic School to help families in need provide an education to their children. -

Spring/Summer 2005 — Vol

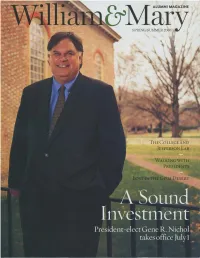

W&M CONTENTS SPRING/SUMMER 2005 — VOL. 70, NO. 3/4 FEATURES William and Mary English Professor Henry Hart traveled 34 AT WILLIAM AND MARY, 40 through Northern China to research the life of his mis- THE NICHOL IS STRONG sionary great-grandfather. Introducing the College’s 26th President BY MELISSA V. PINARD 38 FROM GRAPE TO GLASS Childhood Roots Make for Robust Wine Label BY DANIELLA J. GROSSMAN ’06 40 LOST IN THE GOBI DESERT A Professor’s Journey Through Northern China BY HENRY W. HART 46 WALKING WITH PRESIDENTS The Story of Secret Service Agent John Pforr ’60 BY SANDRA K. JACKSON ’05 50 ACCELERATING W&M’s Relationship with Jefferson Lab BY SYLVIA CORNELIUSSEN DEPARTMENTS 5 PUBLISHER’S NOTE 32 PHILANTHROPY 17 6 MAILBOX 61 CLASS NOTES 9 AROUND THE WREN 112 VITAL STATISTICS 15 VIEWPOINT 126 WHO, WHAT, WHERE 17 ALUMNI SPIRIT 128 CIRCA 22 JUST OFF DOG STREET Karen R. Cottrell ’66, M.Ed. ’69, Ed.D. ’84 has been named executive vice president 25 ARTS & HUMANITIES ON THE COVER: President-elect Gene R. Nichol of the Alumni Association. stands on the Wren portico. TOP PHOTO: AXEL ODELBERG; BOTTOM PHOTO: CHRIS SMITH/PHOTOGRAPHY TOP PHOTO: AXEL ODELBERG; 29 TRIBE SPORTS PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS SMITH/PHOTOGRAPHY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING/SUMMER 2005 3 PUBLISHER’SNOTE SPRING/SUMMER 2005 VOLUME 70, NUMBER 3/4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Walter W. Stout ’64, President Proud Past, Henry H. George ’65, Vice President Marilyn Ward Midyette ’75, Treasurer Russell E. Brown Jr. ’74, Secretary James E. Ukrop ’60, L.H.D. -

465 Info E.P65

May 2007 465/1 Information No. 465 (English) May 2007 Indonesia: Interreligious Dialogue Symposium Oblate representatives from various countries in the on the role and position of women in the Indonesian Asia-Oceania region gathered in Yogyakarta, Indo- Muslim Society in which she promoted vigorously a nesia, for a 3-day Interreligious Dialogue Sympo- Muslim form of contemporary gender equality in the sium on Islam, March 3-6, 2007. The symposium family and wider society.” was a follow-up of the mandate of the 34th General Chapter 2004, “That the General Council and Each contribution was followed by questions and Oblate units explore, facilitate, and support the discussion. Time was also allotted for some Oblates existence and establishment of communities and to share their varying experiences in ministry among support groups of Oblates whose focus will be Muslims, some of which were hopeful, some ex- inter-religious and inter-cultural dialogue, par- tremely demanding and exhausting. ticularly in Muslim, Hindu or Buddhist milieus, and among autochthonous people.”(WH 6). Indonesia is the largest Muslim country in the world and is known as a tolerant society. The rise of ex- The gathering was organized by the Asia/Oceania tremist Islam in the country, however, is threatening Interreligious Dialogue Committee headed by Fr. the peaceful co-existence and harmonious relation- Andri ATMAKA, the Provincial of Indonesia, with ship of Muslims and Christians. Fr. Sowriappan LOORTHUSAMY (India) and Fr.Roberto LAYSON (Philippines) as members. Fr. Oblates from Natal, Senegal, Sahara, Indonesia and Oswald FIRTH, Assistant General and portfolio Philippines also shared their experiences, pointing holder of Mission and Ministries and Fr. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC VISIT OF HIS HOLINESS POPE JOHN PAUL II TO AZERBAIJAN AND BULGARIA EUCHARISTIC CELEBRATION HOMILY OF THE HOLY FATHER Baku Sports Palace Thursday, 23 May 2002 1. "Honour to you who believe!" (1 Pt 2:7). Yes, beloved brothers and sisters of the Catholic community of Baku, and all of you who come from the Catholic communities in the neighbouring countries, "honour to you who believe!" I greet the Christians of the Orthodox Church who have joined us for this solemn moment of prayer, with their Bishop, Alexander. To them too I address the words of the Apostle Peter to the first Christians: "Honour to you who believe!". The universal Church pays tribute to all those who succeeded in remaining faithful to their Baptismal commitments. I am thinking in particular of those who live permanently in this country and who experienced the tragedy of Marxist persecution, and bore the consequences of their faithful attachment to Christ. Brothers and sisters, you saw your religion mocked as mere superstition, as an attempt to escape the responsibilities of engagement in history. For this reason you were regarded as second class citizens and were humiliated and marginalized in many ways. 2. "Honour to you who believe!" Honour to your grandfathers and grandmothers, to your fathers and mothers, who nurtured the seed of faith in you, nourished it with prayer, and helped it to grow and bear fruit. I wish to repeat once again, honour also to you, the holy Orthodox Church; you opened your doors to the Catholic faithful, who were without fold or shepherd. -

NOVA ET VETERA RP PROVINCE NEWSLETTER November-December 2016 Vol

NOVA ET VETERA RP PROVINCE NEWSLETTER November-December 2016 Vol. 52 No. 11 “ By Jean-Baptiste Mubibi, CICM Mission is an essential attribute of our identity as CICM. Just like Jesus was sent by the Father, we are also sent to pursue God‟s Mission through various ad extra and ad intra involvements. Thus, our pioneering spirit, our zeal to be in the periphery, our option to minister in the frontier-situations, and our universal brotherhood remain valuable assets in the establishment of the local Church. And when all this is in place, then we could re-echo the inspiring words of Theophile Verbist in his letter to Jacques Bax: “We have a Good and Beautiful Mission”. “The harvest is abundant, but laborers are few”… There are a large number of possible missionary commitments; there are various areas of pastoral involvements. As a matter of fact, many Church Leaders have appealed of our missionary services. Well, not to boast ourselves, but this is merely because of the good and beautiful mission we do undertake. However, most of these requests can‟t be yet addressed due to our limited resources and personnel at hand. NOVA ET VETERA • NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2016 2 In the Acts of the 14th CICM become then humble agents and General Chapter, it affirms that, “the instruments in God‟s vineyard. Provinces must define and identify All Missions stations and their missionary priorities”. Then from Parishes entrusted to our pastoral the RP Provincial Assembly of July care as CICM are valuable venues 2015 which led to the formulation of that offer great opportunities to the RP Provincial Missionary Project, respond to various missionary we came to articulate specific ad extra ventures or priorities. -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals.