Redalyc.The Hydromythology and the Legend from Natural Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology (2007)

P1: JzG 9780521845205pre CUFX147/Woodard 978 0521845205 Printer: cupusbw July 28, 2007 1:25 The Cambridge Companion to GREEK MYTHOLOGY S The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology presents a comprehensive and integrated treatment of ancient Greek mythic tradition. Divided into three sections, the work consists of sixteen original articles authored by an ensemble of some of the world’s most distinguished scholars of classical mythology. Part I provides readers with an examination of the forms and uses of myth in Greek oral and written literature from the epic poetry of the eighth century BC to the mythographic catalogs of the early centuries AD. Part II looks at the relationship between myth, religion, art, and politics among the Greeks and at the Roman appropriation of Greek mythic tradition. The reception of Greek myth from the Middle Ages to modernity, in literature, feminist scholarship, and cinema, rounds out the work in Part III. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology is a unique resource that will be of interest and value not only to undergraduate and graduate students and professional scholars, but also to anyone interested in the myths of the ancient Greeks and their impact on western tradition. Roger D. Woodard is the Andrew V.V.Raymond Professor of the Clas- sics and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Buffalo (The State University of New York).He has taught in the United States and Europe and is the author of a number of books on myth and ancient civiliza- tion, most recently Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. Dr. -

The Limits of Communication Between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns

Body Language: The Limits of Communication between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns. Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bridget Susan Buchholz, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Sarah Iles Johnston Fritz Graf Carolina López-Ruiz Copyright by Bridget Susan Buchholz 2009 Abstract This project explores issues of communication as represented in the Homeric Hymns. Drawing on a cognitive model, which provides certain parameters and expectations for the representations of the gods, in particular, for the physical representations their bodies, I examine the anthropomorphic representation of the gods. I show how the narratives of the Homeric Hymns represent communication as based upon false assumptions between the mortals and immortals about the body. I argue that two methods are used to create and maintain the commonality between mortal bodies and immortal bodies; the allocation of skills among many gods and the transference of displays of power to tools used by the gods. However, despite these techniques, the texts represent communication based upon assumptions about the body as unsuccessful. Next, I analyze the instances in which the assumed body of the god is recognized by mortals, within a narrative. This recognition is not based upon physical attributes, but upon the spoken self identification by the god. Finally, I demonstrate how successful communication occurs, within the text, after the god has been recognized. Successful communication is represented as occurring in the presence of ritual references. -

Perseus, the Maiden Medusa, and the Imagery of Abduction

HESPERIA 76 (2007) PERSEUS, THE MAIDEN Pages 73-ios MEDUSA, AND THE IMAGERY OF ABDUCTION ABSTRACT on Classical the author that the of Focusing red-figure vases, argues appearance the beautiful Medusa, which has been explained previously as an evolutionary development from the monstrous Archaic type, is determined by discursive context rather than by chronology. Painters used the beautiful Gorgon to certain about Perseus's it is not clear convey messages victory, though always whether she ismeant to evoke humor or pathos. The author further shows that Medusa's death was figured as a perversion of the erotic abductions common s to many Greek myths, and points out the beautiful Gorgon affinities with as abducted maidens such Persephone, Thetis, and Helen. on Among the events depicted the Pseudo-Hesiodic shield of Herakles is scene the flight of Perseus from Medusas sisters.1 The poet renders the in unforgettably vivid terms: Tai ?? uet' ccutov Topyovec ccttatito? xe koci on (paxal eppcoovio ??peva? uocTc?eiv. etc! ?? %?copou ??auocvxo? on 1. For useful suggestions drafts ?awouaecov ??%eoK? gcxko? juey?Acoopuuay?q) of this article, I thank Hedreen, Guy Kai em ?? Laurialan Reitzammer, Albert Hen ?c^?a ?ay?co?/ ?covpoi ?pcxKovxe ?OIG) richs, and the two anonymous Hes ?7Ul?)p?UVT' ?7UK\)pTG)OVT? Kapnva. reviewers. I am also to xco peria grateful Atxjia?ov ?' apa y?* p?v?i ?' ?x?paaaov o?ovxa? and to Melissa Haynes audiences ?ypia ?Epicopivco. ?nl ?? ?Eivo?ai Kapf|voi? at and Harvard Rutgers University Topy??oi? ??ov??TO p?ya? Oo?oc. University for their advice and sug and to the of gestions, Department And after him rushed the Gorgons, unapproachable and unspeakable, at Classics Harvard University, which as longing to seize him: they trod upon the pale adamant, the shield covered the cost of the illustrations. -

Perseus & Phineus / Ricci

J. Paul Getty Museum Education Department Gods, Heroes and Monsters Curriculum Information and Questions for Teaching Perseus Confronting Phineus..., Sebastiano Ricci Perseus Confronting Phineus with the Head of Medusa Sebastiano Ricci Italian, about 1705–1710 Oil on canvas 25 3/16 x 30 5/16 in. 86.PA.591 In Greek mythology, the hero Perseus was famous for killing Medusa, the snake-haired Gorgon whose grotesque appearance turned men to stone. This painting, however, shows a later episode from the hero's life. At Perseus's wedding, the celebration was interrupted by a mob led by Phineus, an unsuccessful suitor to his fiancé Andromeda. After a fierce battle, Perseus warned his allies to turn away their eyes while he revealed the head of Medusa to his enemies. In the midst of battle, Phineus and his cohorts are turned to stone. Ricci depicted the fight as a forceful, vigorous battle. In the center, Perseus lunges forward, his muscles taut as he shoves the head of Medusa at Phineus and his men. One man holds up a shield, trying to reflect the horrendous image and almost losing his balance. Behind him, soldiers already turned to stone are frozen in mid-attack. All around, other men have fallen and are dead or dying. Ricci used strong diagonals and active poses to suggest energetic movement. About the Artist Sebastiano Ricci (Italian, 1659–1734) One of the principal figures in the revival of Venetian painting in the 1700s, Sebastiano Ricci came from a noted family of artists. After formal artistic training in Venice, he traveled widely, working in Vienna, London, and Paris. -

The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses Into Historic Age Witches and Monsters

The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses Miriam Robbins Dexter Special issue 2011 Volume 7 The Monstrous Goddess: The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses into Historic Age Witches and Monsters Miriam Robbins Dexter An earlier form of this paper was published as 1) to demonstrate the broad geographic basis of “The Frightful Goddess: Birds, Snakes and this iconography and myth, 2) to determine the Witches,”1 a paper I wrote for a Gedenkschrift meaning of the bird and the snake, and 3) to which I co-edited in memory of Marija demonstrate that these female figures inherited Gimbutas. Several years later, in June of 2005, the mantle of the Neolithic and Bronze Age I gave a lecture on this topic to Ivan Marazov’s European bird and snake goddess. We discuss class at the New Bulgarian University in who this goddess was, what was her importance, Sophia. At Ivan’s request, I updated the paper. and how she can have meaning for us. Further, Now, in 2011, there is a lovely synchrony: I we attempt to establish the existence of and have been asked to produce a paper for a meaning of the unity of the goddess, for she was Festschrift in honor of Ivan’s seventieth a unity as well as a multiplicity. That is, birthday, and, as well, a paper for an issue of although she was multifunctional, yet she was the Institute of Archaeomythology Journal in also an integral whole. In this wholeness, she honor of what would have been Marija manifested life and death, as well as rebirth, and Gimbutas’ ninetieth birthday. -

Death and the Female Body in Homer, Vergil, and Ovid

DEATH AND THE FEMALE BODY IN HOMER, VERGIL, AND OVID Katherine De Boer Simons A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Depart- ment of Classics. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Sharon L. James James J. O’Hara William H. Race Alison Keith Laurel Fulkerson © 2016 Katherine De Boer Simons ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT KATHERINE DE BOER SIMONS: Death and the Female Body in Homer, Vergil, and Ovid (Under the direction of Sharon L. James) This study investigates the treatment of women and death in three major epic poems of the classical world: Homer’s Odyssey, Vergil’s Aeneid, and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I rely on recent work in the areas of embodiment and media studies to consider dead and dying female bodies as representations of a sexual politics that figures women as threatening and even mon- strous. I argue that the Odyssey initiates a program of linking female death to women’s sexual status and social class that is recapitulated and intensified by Vergil. Both the Odyssey and the Aeneid punish transgressive women with suffering in death, but Vergil further spectacularizes violent female deaths, narrating them in “carnographic” detail. The Metamorphoses, on the other hand, subverts the Homeric and Vergilian model of female sexuality to present the female body as endangered rather than dangerous, and threatened rather than threatening. In Ovid’s poem, women are overwhelmingly depicted as brutalized victims regardless of their sexual status, and the female body is consistently represented as bloodied in death and twisted in metamorphosis. -

A Dictionary of Names

A Dictionary of Names Dates are 'A.o.' unless otherwise stated; they also conform to modem usage, not to the elaborate chronological scheme which Ralegh had to construct in the light of the accepted short age of the world (see entry under 'Adam'). The entries on the kings of Israel and Judah are clarified in the table given below, p. 4I5· Abel: 2nd son of Adam (q.v.) Abia: see next entry Abijah: King of Judah (see Table, p. 4I 5) Abraham (21st cent. B.c.?): Hebrew patriarch, led his family from Chaldea to Canaan, then Egypt 'Academics': adherents of Plato's philosophy Achilles: the Greek hero of the Trojan war Adam: according to tradition, the first man (estimated by Ralegh to have been created in 403 I B.c.) Adonis: beloved of Venus, killed by a boar Aelian (3rd cent. or earlier): Roman historian Aemilius Paulus: see Paulus Aemilius Aemilius, Paulus (d. I 529): Italian chronicler of French history Agar: see Hagar Agathocles: tyrant of Syracuse (3I6-304 B.c.) and king (304-289) Agathon (late 5th cent. B.c.): Athenian tragic poet Agesilaus II (445-361 B.c.): Spartan king and general Agricola, G. Julius (37-93): Roman general and statesman Ahab: King of Israel (see Table, p. 41 5), personification of wickedness Ahaz: King of Judah (see Table, p. 4I 5) Ahaziah: King of Israel (see Table, p. 41 5) Ahaziah (also Jehoahaz): King of Judah (see Table, p. 41 5) Alba: see Alva AlbiU:ovanus Pedo ( rst cent.): Roman poet Alcinous: in the Odyssey, king of the Phaeacians Alcuin (c. -

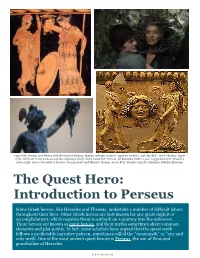

Quest Heroes Introduction to Perseus (De Boer)

Upper left: Perseus and Athena with the head of Medusa. Apulian red figure krater ( Taporley Painter). 400-385 BCE. MFA—Boston. Upper right: still from Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief (2010). Lower left: Perseus, by Benevuto Cellini, 1554. Loggia dei Lanzi (Florenc) Lower right: terra-cotta relief of Perseus, Gorgon-head, and Minerva. Roman, 36-28 BCE. Temple of Apollo Palatinus. Palatine Museum. The Quest Hero: Introduction to Perseus Some Greek heroes, like Heracles and Theseus, undertake a number of difficult labors throughout their lives. Other Greek heroes are best known for one great exploit or accomplishment, which requires them to embark on a journey into the unknown. These heroes are known as quest heroes, and their myths sometimes share common elements and plot points. In fact, some scholars have argued that the quest myth follows a predictable narrative pattern, sometimes called the “monomyth” or “one and only myth. One of the most ancient quest heroes is Perseus, the son of Zeus and grandfather of Heracles. © K. De Boer (2018) Conception & Birth Perseus is (according to mythological chronology) the oldest Greek hero. He is the son of Zeus by the mortal woman Danaë. Danaë’s father had heard a prophecy that his grandson would be his undoing, so he locked his daughter in a tower to keep her from conceiving a child. Zeus, however, was able to enter the tower as a rain of gold coins.When Danaë’s father discovered she had born a child, he locked them both in a chest and set it adrift on the ocean. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Greek Mythology Link (Complete Collection)

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • Español • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. This PDF contains portions of the Greek Mythology Link COMPLETE COLLECTION, version 0906. In this sample most links will not work. THE COMPLETE GREEK MYTHOLOGY LINK COLLECTION (digital edition) includes: 1. Two fully linked, bookmarked, and easy to print PDF files (1809 A4 pages), including: a. The full version of the Genealogical Guide (not on line) and every page-numbered docu- ment detailed in the Contents. b. 119 Charts (genealogical and contextual) and 5 Maps. 2. Thousands of images organized in albums are included in this package. The contents of this sample is copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. To buy this collection, visit Editions. Greek Mythology Link Contents The Greek Mythology Link is a collection of myths retold by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, published in 1993 (available at Amazon). The mythical accounts are based exclusively on ancient sources. Address: www.maicar.com About, Email. Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. ISBN 978-91-976473-9-7 Contents VIII Divinities 1476 Major Divinities 1477 Page Immortals 1480 I Abbreviations 2 Other deities 1486 II Dictionaries 4 IX Miscellanea Genealogical Guide (6520 entries) 5 Three Main Ancestors 1489 Geographical Reference (1184) 500 Robe & Necklace of -

The Medusa Gaze in Contemporary Women's Fiction

The Medusa Gaze in Contemporary Women’s Fiction Copyright and Permissions: 1) Parts of chapters 1, 2 and 5 originally appeared in Mosaic, a journal for the interdisciplinary study of literature, Volume 46, issue 4 (2013): 163-182. 2) Contract granting permission to use the photograph of The Temple of Artemis Medusa from the archives of the German Archaeological Institute DAI-Neg.-No. D-DAI-ATH-1975/885. Photographer Hermann Wagner. 3) Pages 116, 145, 233 (144 words) from The Sadeian Woman by Angela Carter. Published by Virago, 1979. © Angela Carter. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN. 4) Page 233 (70 words) from The Passion of New Eve by Angela Carter. Published by Gollanz, 1977. © Angela Carter. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN. 5) Page 167 (39 words) from Burning Your Boats by Angela Carter. Published by Henry Holt & Co, 1996. © Angela Carter. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN. 6) Pages 167-8, 169, 216 (321 words) from Still Life by A.S. Byatt. Published by Chatto & Windus, 1985. © A.S. Byatt. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN. 7) Page 93 (138 words) from The Game by A.S. Byatt. Published by Chatto & Windus, 1967. © A.S. Byatt. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN. -

Ssnakes, Sstorytelling, and Sserious Leisure by Anna Louise Borynec A

Exploring the Digital Medusa: Ssnakes, Sstorytelling, and Sserious Leisure by Anna Louise Borynec A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Arts and Master of Library and Information Studies Digital Humanities and School of Library and Information Studies University of Alberta © Anna Louise Borynec, 2019 Abstract This research project collected a sample of nine single-authored websites of classical mythology in order to determine whether they could be conceived of as a serious leisure activity under Robert A. Stebbins' Serious Leisure Perspective. Data was manually collected from these websites using a customized rubric that focused on the authors of these websites, rather than their users, and which evolved organically throughout the data collection process. The respective articles on each website about the mythological figure of Medusa was used as a case study for all such articles. Analysis of these authors and their websites was done using three branches of investigation represented by each of the three chapters: applying the Serious Leisure Perspective (SLP) in order to understand how these websites function as leisure activities and fit into existing models of leisure; applying three perspectives borrowed from Library and Information Studies/Science(s) (LIS) (Information Behaviour, Information Architecture, and Bibliometrics) in order to identify and analyze the information phenomena occurring on these websites; and applying the perspectives common in studies of Adaptation in order to understand these websites as a part of a larger interpretive and expressive tradition in an interdisciplinary context. Inductive qualitative analysis was then performed on the results of each branch of analysis—tying the three approaches together—and revealing the extensive dedication of these authors to their websites, urging scholars to take them (and other similar hobbyist websites) as seriously as their creators do.