Foundations for Social Impact Bonds How and Why Philanthropy Is Catalyzing the Development of a New Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2010—2011 Health Programs Financial Information Leader in Disease Independent Auditors’ Report

Celebrating 30 years of waging peace, fighting disease, and building hope 30 ANNUAL REPORT 2010—2011 HEALTH PROGRAMS FINANCIAL INFORMATION Leader in Disease Independent Auditors’ Report . 64 Eradication and Elimination . 20 Financial Statements . 65 Partner for Village-Based Notes to Statements . 70 Health Care Delivery . 22 OUR COMMUNITY The Carter Center at a Glance . 2. Voice for Mental Health Care . 24 The Carter Center Around Aontents Message from President Health Year in Review . 26 the World . 84 CJimmy Carter . 3 PHILANTHROPY Senior Staff . 86 Interns . 86 Our Mission . 4 A Message About Our Donors . 32 A Letter from the Officers . 5 International Task Force for Donors with Cumulative Lifetime Disease Eradication . 87 Giving of $1 Million or More . 33 PEACE PROGRAMS Friends of the Inter-American Pioneer of Election Observation . 8 Donors During 2010–2011 . 34 Democratic Charter . 87 Trusted Broker for Peace . 10 Ambassadors Circle . 48 Mental Health Boards . 88 Champion for Human Rights . 12 Legacy Circle . 58 Board of Councilors . 89 Peace Year in Review . 14 Founders . 61 Board of Trustees . 92 A woman works at a small-scale subsistence mine in the province of Katanga, southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo . The Carter Center’s work in the country is raising awareness about the nation’s lucrative mining industry, which generates huge profits while impoverished local communities receive few of the benefits . 1 The Carter Center at a Glance Overview • Strengthening international standards for human rights The Carter Center was founded in 1982 by former U.S. and the voices of individuals defending those rights in President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, in their communities worldwide partnership with Emory University, to advance peace and • Pioneering new public health approaches to preventing health worldwide. -

Limits and Contradictions of Labour Investment Funds

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by R-libre Managing Workers’ Capital? Limits and Contradictions of Labour Investment Funds Ian Thomas MacDonald is Assistant Professor in the School of Industrial Relations at Université de Montréal. His research interests include labour organizing strategies, labour politics and radical political economy. His work has appeared in Labor Studies Journal, Socialist Register, and the British Journal of Industrial Relations. He is the editor of Unions and the City: Negotiating Urban Change (Cornell ILR Press, 2017). Mathieu Dupuis: is Assistant professor in labor relations, TÉLUQ Montréal – University of Québec. He is conducting research on trade unions, comparative employment relations, multinational corporations, and the manufacturing sector. Recent publication: 2018. “Crafting alternatives to corporate restructuring: Politics, institutions and union power in France and Canada” European Journal of Industrial Relations, 24(1): 39-54. Abstract: Labour-controlled investment is often touted as an alternative, pro-worker form of finance. Since 1983, the province of Québec in Canada has experimented with workers participation in the form of workers funds controlled by the two major trade union federations. Drawing on research from secondary sources, archival material and semi-structured interviews, this paper offers a comprehensive portrait of one of Québec main workers’ funds, the FTQ Solidarity Fund. To date very little has been said about the impact of workers funds on firm governance, employment quality and labour relations. We argue that any attempt to use investment to shape firm behaviour in the interests of workers and local unions is a limited and contradictory project. -

Financing Growth in Innovative Firms: Consultation

Financing growth in innovative frms: consultation August 2017 Financing growth in innovative frms: consultation August 2017 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identifed any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-912225-08-8 PU2095 Contents Page Foreword 3 Executive summary 5 Chapter 1 Introduction 7 Chapter 2 The patient capital gap 9 Chapter 3 Strengths and weaknesses in patient capital 17 Chapter 4 Root causes (1): deployment of / demand for patient capital 29 Chapter 5 Root causes (2): supply of capital 35 Chapter 6 Current interventions 43 Chapter 7 Implications for policy 51 Annex A List of consultation questions 61 Annex B Terms of reference for the review 63 Annex C Terms of reference for and members of the Industry Panel 65 Annex D Data sources 69 1 Foreword Productivity is important. As I set out in my speech at the Mansion House earlier this summer, improvements in productivity ultimately drive higher wages and living standards. This makes it much more than just another metric of economic performance. -

Impact Bonds in Developing Countries

IMPACT BONDS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: Early Learnings from the Field 2 | IMPACT BONDS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES IMPACT BONDS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: Early Learnings from the Field SEPTEMBER 2017 Emily Gustafsson-Wright is a fellow at the Center for Universal Education at Brookings Izzy Boggild-Jones is a research analyst at the Center for Universal Education at Brookings Dean Segell is a manager at Convergence Justice Durland is a knowledge associate at Convergence ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank Brookings gratefully acknowledges many people for their contributions the program support provided to the to this study. First, Alison Bukhari, Center for Universal Education by the Toby Eccles, Safeena Husain, Jane Government of Norway. Newman, Peter Vanderwal and Maya Ziswiler for their helpful comments, Brookings recognizes that feedback and insight on earlier drafts the value it provides is in its of the report. In addition, we would absolute commitment to quality, like to thank all those who supported independence, and impact. Activities with data collection for the Deal Book, and provided real time updates on the supported by its donors reflect this factsheets for each deal. We would commitment. also like to acknowledge those who participated in the impact bonds workshop in London in November 2016, whose valuable insights have Convergence is an institution that formed the core of this report. We connects, educates, and supports are particularly grateful for the investors to execute blended finance contributions of stakeholders involved transactions that increase private in the contracted impact bonds with sector investment in emerging whom we have had more in-depth markets. -

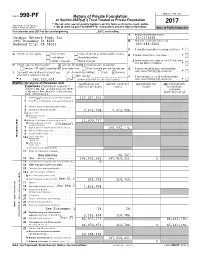

ONFI-2017-990-PF.Pdf

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2017 G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2017 or tax year beginning , 2017, and ending , A Employer identification number Omidyar Network Fund, Inc 20-1173866 1991 Broadway St #200 B Telephone number (see instructions) Redwood City, CA 94063 650-482-2500 C If exemption application is pending, check here. G G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D1Foreign organizations, check here. G Final return Amended return Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach computation . G H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here. G IJFair market value of all assets at end of year Accounting method: CashX Accrual (from Part II, column (c), line 16) Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination G $ 545,202,008. (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here. G Part I Analysis of Revenue and (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements Expenses (The total of amounts in expenses per books income income for charitable columns (b), (c), and (d) may not neces- purposes sarily equal the amounts in column (a) (cash basis only) (see instructions).) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received (attach schedule). -

Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should Or Could to Stop Online Fraud?

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 52 Issue 2 Article 8 3-2000 Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud? James M. Snyder Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Communications Law Commons, Consumer Protection Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, James M. (2000) "Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud?," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 52 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol52/iss2/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE Online Auction Fraud: Are the Auction Houses Doing All They Should or Could to Stop Online Fraud? James M. Snyder* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 454 II. COMPLAINTS OF ONLINE AUCTION FRAUD INCREASE AS THE PERPETRATORS BECOME MORE CREATV ................................. 455 A. Statistical Evidence of the Increase in Online Auction Fraud.................................................................................... 455 B. Online Auction Fraud:How Does It Happen? ..................... 457 1. Fraud During the Bidding Process .................................. 457 2. Fraud After the Close of the Auction .............................. 458 IlL VARIOUS PARTES ARE ATrEMPTNG TO STOP ONLINE AUCTION FRAUD .......................................................................... 459 A. The Online Auction Houses' Efforts to Self-regulate........... -

Accelerating Energy Access

ACUMEN 2018 ACCELERATING ENERGY ACCESS: THE ROLE OF PATIENT CAPITAL ACUMEN WOULD LIKE TO ACKNOWLEDGE OUR PARTNERS THAT GENEROUSLY SUPPORT THE PIONEER ENERGY INVESTMENT INITIATIVE STEVE ROSS & THE BERNARD & ANNE SPITZER SHELLEY SCHERER CHARITABLE TRUST GLOBAL OFFICES SPECIAL THANKS ACCRA, GHANA Special thanks to our peer reviewers Saad Ahmad, David Aitken, Magdalena Banasiak, Morgan DeFoort, Fabio De Pascale, BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA Christine Eibs-Singer, Peter George, Steven Hunt, Neha Juneja, KARACHI, PAKISTAN Jill Macari, Damian Miller, Jesse Moore, Willem Nolens, Steve Ross, LONDON, ENGLAND Peter Scott, Ajaita Shah, Manoj Sinha, Ned Tozun, Nico Tyabji, MUMBAI, INDIA Hugh Whalan, and David Woolnough NAIROBI, KENYA Special thanks to Carlyle Singer for her strategic guidance and NEW YORK, U.S.A. Harsha Mishra for his analytical research. Additional thanks SAN FRANCISCO, U.S.A. to the Acumen team: Sasha Dichter, Kat Harrison, Kate Montgomery, Jacqueline Novogratz, Sachindra Rudra, and Yasmina Zaidman Lead Authors: Leslie Labruto and Esha Mufti Table of Contents FOREWORD 02 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 04 INTRODUCTION 06 1. ENERGY SNAPSHOT: 08 ACUMEN’S TRACK RECORD FOR INVESTING IN ENERGY ACCESS 2. THE PIONEER GAP: 12 HOW HAS THE INFLUX OF CAPITAL AFFECTED ENTREPRENEURS? 3. NEED FOR CAPITAL: 16 FILLING GAPS IN OFF-GRID ENERGY MARKETS TODAY 4. THE BIG PICTURE: 26 WHAT IS THE OPTIMAL MIX FOR SCALING ENERGY ACCESS COMPANIES? 5. REACHING THE POOR: 38 USING PATIENT CAPITAL TO ACCELERATE IMPACT 6. BEYOND CAPITAL: 46 WHAT DO ENERGY ACCESS STARTUPS NEED? 7. FACILITATING EXITS: 48 SENDING THE RIGHT MARKET SIGNALS 8. CONCLUSION: 56 WORKING TOGETHER TO CATALYZE ENERGY ACCESS APPENDIX 58 CASEFOREWORD STUDY Jacqueline Novogratz FOUNDER & CEO Dear Reader, I am pleased to share Acumen’s Accelerating Energy Access: The Role of Patient Capital report with you. -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Threat from the Right Intensifies

THREAT FROM THE RIGHT INTENSIFIES May 2018 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 Meeting the Privatization Players ..............................................................................3 Education Privatization Players .....................................................................................................7 Massachusetts Parents United ...................................................................................................11 Creeping Privatization through Takeover Zone Models .............................................................14 Funding the Privatization Movement ..........................................................................................17 Charter Backers Broaden Support to Embrace Personalized Learning ....................................21 National Donors as Longtime Players in Massachusetts ...........................................................25 The Pioneer Institute ....................................................................................................................29 Profits or Professionals? Tech Products Threaten the Future of Teaching ....... 35 Personalized Profits: The Market Potential of Educational Technology Tools ..........................39 State-Funded Personalized Push in Massachusetts: MAPLE and LearnLaunch ....................40 Who’s Behind the MAPLE/LearnLaunch Collaboration? ...........................................................42 Gates -

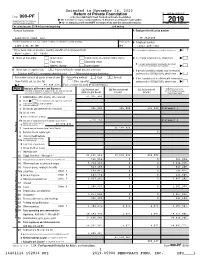

2019 Form 990-PF

Extended to November 16, 2020 Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation | Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury 2019 Internal Revenue Service | Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2019 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number Democracy Fund, Inc. 38-3926408 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 1200 17th St NW 300 (202) 420-7943 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ~ | Washington, DC 20036 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ~~ | Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ~~~~ | X H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ~ | X I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ~ | | $ 87,348,415. -

A Conversation with Hawai'i's Own Pierre Omidyar Taking the Hawai'i International Confere

Volume 33, Number 1 Spring 2010 INSIDE: Be True to Your School | A Conversation with Hawai‘i’s Own Pierre Omidyar Taking the Hawai‘i International Conference on System Sciences to New Heights DEAn’s MessAGE “We are proud to announce that our undergraduate program has, for the first time, been named as one of the nation’s top business programs by Bloomberg BusinessWeek.” Aloha, Conference on System Sciences into nation’s best by Bloomberg BusinessWeek. The Shidler College of Business one of the world’s leading gatherings on This is truly a credit to our entire faculty is a special place where people of all information systems applications. and staff who have worked tirelessly to cultures and backgrounds come together For those of you who are aspiring strengthen our programs, student services, to share ideas, dreams and business entrepreneurs, be sure to check out the internships and career placement. aspirations. Our global community of excerpts from our exclusive interview It has been a remarkable six months alumni, students, faculty and business with eBay founder Pierre Omidyar. As the and we thank you for sharing an interest professionals lies at the heart of our featured speaker for the Kı¯papa i ke Ala in all that we have accomplished. As success and is what makes this such a Lecture, he inspired us all to dream big. always, we hope that you enjoy this issue unique place to learn, grow and develop. Shidler pride continues to reign of Shidler Business. We welcome your The stories and articles in this issue of strong among our alumni. -

Social Capital's Performance Vs the S&P

Social Capital’s performance vs the S&P 500 Annualized Percentage Change Gross IRR In S&P 500 with dividends included 2011 - 2018................ 29.4% 13.5% 2011 - 2019................ 32.9% 15.0% Overall Gain 997% 325% To the supporters and stakeholders of Social Capital: This is the second of our annual letters where we discuss our investments and other thoughts on technology, markets, and our mission. Eight and a half years ago, we started Social Capital to tackle hard problems like cancer, space exploration and climate change at a time when few investors were doing so. While many investors fawned over social networks, photo-sharing apps, and other consumer-oriented investments, we invested in healthcare, education, and frontier technology businesses like space exploration and artificial intelligence. Many of the companies we backed were initially unable to raise money from other institutional investors until we stepped in to give them the long-term, patient capital they needed. We hoped that we would be rewarded for these bets in good time. In 2018, this hope started to become a reality and we concluded that the traditional approach of fund management and asset gathering wasn’t going to be enough. It would definitely generate huge fees to put in our pockets but, ultimately, not make a meaningful impact in achieving our mission. This is a difference that makes a difference in today’s increasingly complicated world and so we iterated. We closed ourselves to outside capital and became a technology holding company in mid 2018. As we write to you today, we look forward, optimistically, to the future despite its intermittent calamities.