William Butler Yeats and Edmund Dulac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack B. Yeats

JACK B. YEATS Biography 1871 August 29, Jack Butler Yeats born at 23 Fitzroy Road, London, son of John Butler Yeats, artist, and Susan Pollexfen of Sligo 1879 Went to Sligo to live with his grandparents, William and Elizabeth Pollexfen. He went to school there, and stayed with them until 1887 1887 Rejoined his family in London in order to attend art school. His grandmother was strongly in favour of him following a career as an artist. Attended classes at South Kensington School of Art, Chiswick School of Art, Westminster School of Art. Season ticket for the American Exhibition at Earls Court, starring Buffalo Bill 1888 First black and white illustrations accepted for publication in The Vegetarian in April 1891 Illustrating for Ariel and Paddock Life . First book illustrations 1892 Designing posters for David Allen & Sons in Manchester. Illustrated Irish Fairy Tales by his brother W.B.Yeats 1894 Staff Artist on Lika Joko. In August he married Mary Cottenham White, who had been a student with him in Chiswick, and was eight years older that Jack. They rented a house called 'The Chestnuts' on the River Thames, at Chertsey 1895 First exhibited at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, a watercolour called Strand Races, West of Ireland 1897 Moved to Strete, Devon to live at 'Snail's Castle' (Cashlauna Shelmiddy). Began to concentrate on watercolour painting. Painted his first oil. First one-man show of watercolours in November, at the Clifford Gallery, Haymarket 1898 Jack and Cottie visited Northern Italy, on what seems to have been a belated honeymoon, combined with a celebration of the success of his first solo exhibition the previous year. -

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This Poem Deals with the Dublin Rebellion Of

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This poem deals with the Dublin Rebellion of Easter 1916 which is believed to have been the beginning of modern Ireland, in spite of its immediate failure. Yeats was in Dublin when it happened, and though at first he was against the violence and the bloodshed that accompanied it and he thought the sacrifice of its leaders wasteful, he sympathized with the rebels when sixteen of them were executed. In Stanza One the poet describes the previous lives of the rebels to suggest that they were average or normal citizens who sacrificed their lives for the sake of Irish independence. They were normal Irish people with "vivid faces" and he used to meet them with a nod of the head or saying polite meaningless words. However, he shared with them the love of Ireland: Be certain that they and I But lived where motely is worn The word "motely" means colourful dress which symbolizes Irish people. The stanza ends with "a terrible beauty is born" which may allude to the Birth of Hellen of Troy, Maud Gonne and Ireland because Irish independence will be accompanied by violence and bloodshed. In Stanza Two the poet mentions some of the significant rebels b eginning with "that woman" which refers to Maud Gonne, the most beautiful woman in Ireland according to Ye ats who was with the rebels; she was imprisoned in England after the rising but she escaped to Dublin in 1918. Because of her interest in Irish independence and in politics and argument, her beautiful voice became shrill. -

Imitatio Dantis: Yeats's Infernal Purgatory

Ruttkay díj 2013 Balázs Zsuzsanna Imitatio Dantis: Yeats’s Infernal Purgatory Ille. And did he find himself, Or was the hunger that had made it hollow A hunger for the apple on the bough Most out of reach? and is that spectral image The man that Lapo and Guido knew?1 In theory, there are few things which might be in common between two poets whose poetry could not seemingly be more dissimilar in terms of time, topics, sources and purposes and who are divided from each other by more than six centuries. However, this essay intends to focus on two poets of this kind: the Italian ‘sommo poeta’, Dante Alighieri and the Anglo- Irish symbolist, fin de siècle poet, William Butler Yeats. In fact, their apparent irreconcilability is only the mere surface of the opinion formed on their oeuvres, since Dante did have a significant influence on Yeats whose poetry had two main Dantean decades. The first was characterized by the influence of the Romantics2 and also by the impact of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, while in the second one Yeats managed to create his own interpretation of Dante. Consequently, it is not by accident that “Yeats mentioned Dante over ninety times in his published prose [...] and adapted Dante’s work for parts of at least ten poems, three plays and a story.”3 I chose to draw a parallel between Dante and Yeats because in spite of the fact that they share almost a myriad of common features, this kind of approach to Yeats and his works has been overshadowed by other fascinating topics in which Yeats’s poems and plays abound. -

Edmund Dulac

Edmund Dulac JONKERS RARE BOOKS EDMUND DULAC JONKERS RARE BOOKS 1. Stories From The Arabian Nights Retold by Laurence Housman DULAC, Edmund Hodder and Stoughton, 1907. First Dulac edition, Edition de Luxe. Number 188 of 350 deluxe copies signed by Edmund Dulac. 4to. Full white vellum with gilt lettering and vignettes in blue and gold. Top edge gilt and others untrimmed. Printed on hand made paper. Colour frontis and 49 other colour plates all mounted onto grey art paper and protected by captioned tissue guards. A near fine, bright copy of Dulac’s first major gift book. Vellum uncommonly clean, occasional spots of foxing to the tissue guards. [39778] £2,750 This book is Dulac’s first major commission. It is an impressive volume, including stories from the Arabian Nights, such as Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and The King of the Ebony Isles. The publishers commis- sioned Dulac with the aim of competing for market share with the books illustrated by Arthur Rackham. This deluxe version of the Christmas Gift Book showed what a good choice they made. Dulac’s colour palette of deep blue shades is a triumph, transporting the reader to the sultry evenings of the Middle East. EDMUND DULAC JONKERS RARE BOOKS 2. Stories From The Arabian Nights Retold by Laurence Housman DULAC, Edmund Hodder and Stoughton, 1907. First edition. 4to. Brown buckram with embossed decoration in gilt and blue. Colour frontis and 49 other colour plates all mounted onto grey art paper and protected by captioned tissue guards. The pates are fresh and crisp, not creasing, although one has a tiny corner scuff. -

Graham, Catherine, February 2006, Keep Rejects

Catherine Graham Collection: February 2006, 1. Krans, Horatio Sheafe, William Butler Yeats and the Irish Literary Revival. London: William Heinemann, 1905. 2. Moore, George, Confessions of a Young Man. London and Toronto: William Heinemann, 1935. 3. Meredith, George, A Reading of Life: With Other Poems. Westminster: Archibald Constable, 1901. 4. Synge, J.M., (Robin Skelton ed.), Some Sonnets from “Laura in Death” after the Italian of Frencesco Petrarch. Dolmen Eds. Dublin: Dolmen Press Ltd., 1971. 5. Skelton, Robin (ed.), The Collected Plays of Jack B. Yeats. Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1971. 6. Johnston, Denis, The Brazen Horn: A Non-Book for those, who, in revolt today, could be in command tomorrow. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1976. 7. Skelton, Robin, An Irish Album. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1969. 8. Montague, John, All Legendary Obstacles. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1966. 9. Synge, J.M., My Wallet of Photographs. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1971. 10. Clarke, Austin, Mnemosyne Lay in Dust. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1966. 11. O’Grady, Desmond, The Gododdin. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1977. 12. Bickley, Francis, J.M. Synge and the Irish Dramatic Movement. Toronto: Musson Book Co. 13. Horton, W.T. and W.B. Yeats, A Book of Images. London: Unicorn Press, 1898. 14. Yeats, W.B. (ed.), Beltaine: An Occasional Publication. Nos. 1, 2, 3, 1899-1900. London: Sign of the Unicorn, 1900. 15. Poems and Ballads of Young Ireland, 1888. Dublin: M.H. Gill and Son, 1888. 16. Moore, George, Heloise and Abelard. In two volumes, V.I. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921. 17. Raine, Kathleen, Yeats, The Tarot and the Golden Dawn. -

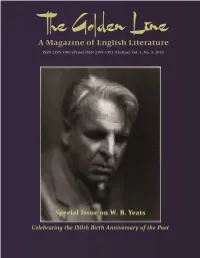

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

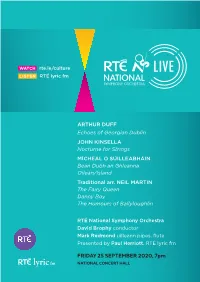

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1986 Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Donald Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 22, no.4, December 1986, p.198-204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pearce: Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats by DONALD PEARCE He made songs because he had a will to make songs and not because love moved him thereto. Ue de Saint-eire VERY POET is, at bottom, a kind of alchemist, every poem an ap E paratus for transn1uting the "base metal" of life into the gold of art. Especially is this true of Yeats, not only as regards the ambient world of other people and events, but also the private one of his own art and thought: "Myself must I remake / Till I am Timon and Lear / Or that William Blake...." So persistent was he in this work of transmutation, and so adept at it, that the ordinary affairs of daily life often must have seemed to him little more than a clumsy version of a truer, more intense life lived in the clarified world of his imagination. However that may have been for Yeats, it is certainly true for his readers: incidents, persons, squabbles with which or whom he was intermittently entangled increas ingly owe what importance they still have for us to the fact of occurring somewhere, caught and finalized, in the passionate world of his poems. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings Across National and Cultural Divides

Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings across National and Cultural Divides Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings across National and Cultural Divides By Yarmila Nikolova Daskalova Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings across National and Cultural Divides By Yarmila Nikolova Daskalova This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Yarmila Nikolova Daskalova All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1380-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1380-8 For Sarkis and Lucia CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Wandering With(out) a Muse: Intertextuality and Romantic Disguise .... 9 New Dimensions in Conceptualizing Beauty and the Principle of Originality in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Baudelaire ...... 24 “A Word that Breathes Distinctly has Not the Power to Die”: The Life of Words in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson and Marina Tsvetaeva ................................................................................ 48 Charles Baudelaire’s “The Voyage” and W. B. Yeats’s “News for the Delphic Oracle”: Politics of Perception and Strategies of Representation in Two Poems on Departure and (Withheld) Arrival ........ 98 Haunting Romanticisms: Day-dreaming and Obsessive Imagery in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe and Peyo Yavorov .............................. 115 W. B Yeats And P. K. Yavorov: Concepts of National Mythopoetics .... 142 W.B.