A Late Caledonian Melange in Ireland: Implications for Tectonic Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Aspects of the Breeding Biology of the Swifts of County Mayo, Ireland Chris & Lynda Huxley

Some aspects of the breeding biology of the swifts of County Mayo, Ireland Chris & Lynda Huxley 3rd largest Irish county covering 5,585 square kilometers (after Cork and Galway), and with a reputation for being one of the wetter western counties, a total of 1116 wetland sites have been identified in the county. Project Objectives • To investigate the breeding biology of swifts in County Mayo • To assess the impact of weather on parental feeding patterns • To determine the likelihood that inclement weather significantly affects the adults’ ability to rear young • To assess the possibility that low population numbers are a result of weather conditions and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. Town Nest Nest box COMMON SWIFT – COUNTY MAYO - KNOWN STATUS – 2017 Sites Projects Achill Island 0 0 Aghagower 1 0 Balla 1 1 (3) Ballina 49 1 (6) Ballycastle Ballinrobe 28 1 (6) Ballycastle 0 0 0 Ballycroy 0 In 2018 Ballyhaunis ? In 2018 Killala 7 Bangor 0 In 2018 0 Belmullet 0 In 2018 Castle Burke 2 0 Bangor 49 0 Castlebar 37 4 (48) (12) Crossmolina Charlestown 14 1 (6) 8 Claremorris 15 2 (9) (2) Crossmolina Cong 3 1 (6) Crossmolina 8 1 (6) Foxford Foxford 16 1 (12) Achill Island 16 14 0 21 Killala 7 1 (6) 0 Charlestown Kilmaine 2 0 0 0 2 Kiltimagh 6 1 (6) 14 Kinlough Castle 10 0 Mulranny Turlough Kiltimagh 6 Knock 0 0 Louisburgh ? In 2018 40 Balla 1 0 Knock Mulranny 0 0 Newport 14 1 (6) X X = SWIFTS PRESENT 46 1 Aghagower Shrule 10 1 (6) Castle Burke Swinford 21 1 (6) POSSIBLE NEST SITES X 2 15 Tourmakeady 0 0 TO BE IDENTIFIED Turlough 2 In 2018 Westport -

Tier 3 Risk Assessment Historic Landfill at Claremorris, Co

CONSULTANTS IN ENGINEERING, ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE & PLANNING TIER 3 RISK ASSESSMENT HISTORIC LANDFILL AT CLAREMORRIS, CO. MAYO Prepared for: Mayo County Council For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Date: September 2020 J5 Plaza, North Park Business Park, North Road, Dublin 11, D11 PXT0, Ireland T: +353 1 658 3500 | E: [email protected] CORK | DUBLIN | CARLOW www.fehilytimoney.ie EPA Export 02-10-2020:04:36:54 TIER 3 RISK ASSESSMENT HISTORIC LANDFILL AT CLAREMORRIS, CO. MAYO User is responsible for Checking the Revision Status of This Document Description of Rev. No. Prepared by: Checked by: Approved by: Date: Changes Issue for Client 0 BF/EOC/CF JON CJC 10.03.2020 Comment Issue for CoA 0 BF/EOC/MG JON CJC 14.09.2020 Application Client: Mayo County Council For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Keywords: Site Investigation, environmental risk assessment, waste, leachate, soil sampling, groundwater sampling. Abstract: This report represents the findings of a Tier 3 risk assessment carried out at Claremorris Historic Landfill, Co. Mayo, conducted in accordance with the EPA Code of Practice for unregulated landfill sites. P2348 www.fehilytimoney.ie EPA Export 02-10-2020:04:36:54 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. -

The Old Coastguard Station, Ross Strand, Killala, Co. Mayo

The Old Coastgua rd Station, Ross Strand, Killala, Co. Mayo This is a unique opportunity to obtain an important historical building that has been carefully converted into a terrace of six 2-storey homes. The conversion has been very carefully carried out to preserve as many features of the old building as possible and retain its original charm and appearance. The location is truly spectacular, on the edge of the beach of the beautiful Ross Strand. The Strand lies in a sheltered bay close to the estuary of the River Moy. It looks out over the Atlantic to Bartra Island, Enniscrone and the open ocean. This is one of the best beaches in County Mayo with large stretches of soft sand and amazing scenery. The coastguard station is approached from the Price Region: €550,000 beach by original stone stairs. There are five similar townhouses, all with the same layout: A living/dining room, kitchen and guest W.C. downstairs and two bedrooms, each with ensuite shower rooms, upstairs. The sixth house utilises the end lookout tower and has three bedrooms, a ground floor bathroom and a study in the tower. All the properties were finished to a good standard but now need some cosmetic refurbishment and modernisation. Until recently the houses were rented out as self-catering holiday homes and achieved good occupancy rates during the summer months. FEATURES One of the best coastal locations in the West of Ireland. Situated on the beach of what is widely considered to be the best strand in Mayo. Spectacular views of Killala Bay, Bartra Island and Enniscrone. -

Price Region: €220,000.00 Main Street, Bangor Erris, County Mayo

Main Street, Bangor Erris, County Mayo Excellent opportunity to acquire a five bedroom family residence in the heart of Bangor Erris. The property is within walking distance to all town amenities. Bangor Erris is located within 10 minutes drive to Geesala, 15 minutes to Claggan Island and 20 minutes to Carne Golf Links and Belmullet. Price Region: €220,000.00 Licence No: 002274 Excellent opportunity to acquire a five bedroom family residence in the heart of Bangor Erris. The property is within walking distance to all town amenities. Bangor Erris is located within 10 minutes drive to Geesala, 15 minutes to Claggan Island and 20 minutes to Carne Golf Links and Belmullet. The ground floor accommodation comprises hall, sitting room, three bedrooms, one ensuite, kitchen/dining area, utility and main bathroom. First floor accommodation comprises two double bedrooms, one shower room and one storage room. Outside the property has a rear landscaped garden with small storage shed. FIRST FLOOR Entrance hallway 1.96m (6'5") x 7.61m (25'0") PVC door with glass insert opens to a bright and welcoming reception area. Tiled floor. Sitting Room 3.98m (13'1") x 3.6m (11'10") Natural light provided by a large front window. The sitting room has an open fireplace and laminate floor. Bedroom 1 3.63m (11'11") x 4.16m (13'8") Located on the ground floor with a large front window. Built in wardrobe and carpet floor. Bedroom 2 3.63m (11'11") x 4.4m (14'5") Double bedroom located at the rear of the property. -

The Few Weeks of My Life That I Spent in Ireland Were a Wonderful Experience and a Good Beginning

The few weeks of my life that I spent in Ireland were a wonderful experience and a good beginning. The Jane C. Waulbaum scholarship allowed me to have this experience, as the funds were used for travel and living expenses, and I thank the Archaeological Institute of America for this fantastic opportunity. I arrived in Dooagh, the village where the Achill Field School is located, nearly twenty-four hours after I departed from the United States, tired and filled with excitement. Not only was I taking the first step in my archaeological career, but was also in Ireland, the very place that I want to pursue my future intellectual endeavors. We did not begin fieldwork immediately. On the first day we had an introduction to the field school, including lectures about Irish archaeology, the history of the field school, and what we would be doing for the next few weeks. The site that we would be working on was the house of the famous Captain Boycott, dated to AD 1854. When Boycott arrived in Keem, a small village to the west of Dooagh, he needed to construct a house quickly and start farming, so he chose to construct it out of "galvanized iron", which is actually corrugated steel. As far as I understand it, he was able to construct his dwelling in less than a week, and added other phases to the house later, this time made from stone. Phase one, the "galvanized iron" portion of the house, at some point caught fire and was destroyed. It was this part of the house that we were excavating. -

County Mayo Game Angling Guide

Inland Fisheries Ireland Offices IFI Ballina, IFI Galway, Ardnaree House, Teach Breac, Abbey Street, Earl’s Island, Ballina, Galway, County Mayo Co. Mayo, Ireland. River Annalee Ireland. [email protected] [email protected] Telephone: +353 (0)91 563118 Game Angling Guide Telephone: + 353 (0)96 22788 Fax: +353 (0)91 566335 Angling Guide Fax: + 353 (0)96 70543 Getting To Mayo Roads: Co. Mayo can be accessed by way of the N5 road from Dublin or the N84 from Galway. Airports: The airports in closest Belfast proximity to Mayo are Ireland West Airport Knock and Galway. Ferry Ports: Mayo can be easily accessed from Dublin and Dun Laoghaire from the South and Belfast Castlebar and Larne from the North. O/S Maps: Anglers may find the Galway Dublin Ordnance Survey Discovery Series Map No’s 22-24, 30-32 & 37-39 beneficial when visiting Co. Mayo. These are available from most newsagents and bookstores. Travel Times to Castlebar Galway 80 mins Knock 45 mins Dublin 180 mins Shannon 130 mins Belfast 240 mins Rosslare 300 mins Useful Links Angling Information: www.fishinginireland.info Travel & Accommodation: www.discoverireland.com Weather: www.met.ie Flying: www.irelandwestairport.com Ireland Maps: maps.osi.ie/publicviewer © Published by Inland Fisheries Ireland 2015. Product Code: IFI/2015/1-0451 - 006 Maps, layout & design by Shane O’Reilly. Inland Fisheries Ireland. Text by Bryan Ward, Kevin Crowley & Markus Müller. Photos Courtesy of Martin O’Grady, James Sadler, Mark Corps, Markus Müller, David Lambroughton, Rudy vanDuijnhoven & Ida Strømstad. This document includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Copyright Permit No. -

Bank of Ireland. High Street, Westport, Co Mayo

FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Bank Of Ireland. High Street, Westport, Co Mayo 671.36 sq m (7,226 sq ft) Property Highlights Contact • Located in a prominent position in Westport Town Centre Sean Coyne • Modern Three story retail banking property extending to Email: [email protected] approximately 671.36 sq m (7,226sq ft) Tel: 091-569181 • Long term Bank of Ireland income (over 15 years unexpired) Patricia Staunton offering AAA covenant strength Email: [email protected] • Let to The Governor & Company of the Bank of Ireland on a Tel: 091-569181 long lease at a current passing rent of €219,480 per annum • For Sale By Private Treaty Cushman & Wakefield 2 Dockgate, Dock Road, • Tenant not affected Galway Ireland Tel: 091-569181 cushmanwakefield.ie Bank Of Ireland. High Street, Westport, Co Mayo The Location The property has been very well maintained both internally and externally with the interior fit-out Westport is County Mayo’s premier tourist refurbished in the past number of years. destination, with the tourism, leisure and service sectors being the largest form of employment. Access to the property is via a public entrance from High Street, there is also a staff only entrance Bridge Street, Shop Street, High Street and James to the building. Street are the main commercial thoroughfares in the town, which together with the Octagon, accommodate the majority of Westport’s retailers Accommodation and a number of licenced premises. Floor Sq m Sq ft The subject property is situated in a high profile position on High Street overlooking the Clock Ground Floor 340 3,659 Tower junction. -

Clew Bay Complex (Comprising a Collection of Drumlins Within Clew Bay) 3

Clew Bay SAC (site code 1482) Conservation objectives supporting document ‐coastal habitats NPWS Version 1 June 2011 Table of Contents Page No. 1 Introduction 3 2 Conservation objectives 5 3 Perennial vegetation of stony banks 5 3.1 Overall objective 6 3.2 Area 6 3.2.1 Habitat extent 6 3.3 Range 6 3.3.1 Habitat distribution 6 3.4 Structure and Functions 7 3.4.1 Functionality and sediment supply 7 3.4.2 Vegetation structure: zonation 7 3.4.3 Vegetation composition: typical species & sub-communities 7 3.4.4 Vegetation composition: negative indicator species 8 4 Saltmarsh habitats 9 4.1 Overall objectives 9 4.2 Area 9 4.2.1 Habitat extent 9 4.3 Range 10 4.3.1 Habitat distribution 10 4.4 Structure and Functions 11 4.4.1 Physical structure: sediment supply 11 4.4.2 Physical structure: creeks and pans 11 4.4.3 Physical structure: flooding regime 11 4.4.4 Vegetation structure: zonation 12 4.4.5 Vegetation structure: vegetation height 12 4.4.6 Vegetation structure: vegetation cover 12 4.4.7 Vegetation composition: typical species & sub-communities 13 4.4.8 Vegetation composition: negative indicator species 13 5 Sand dune habitats 14 5.1 Overall objectives 15 5.2 Area 16 5.2.1 Habitat extent 16 5.3 Range 17 5.3.1 Habitat distribution 17 5.4 Structure and Functions 17 5.4.1 Physical structure: functionality and sediment supply 17 5.4.2 Vegetation structure: zonation 18 5.4.3 Vegetation composition: plant health of dune grasses 19 1 5.4.4 Vegetation composition: typical species & sub-communities 19 5.4.5 Vegetation composition: negative indicator -

3.8 Cultural Heritage

Newport Sewerage Scheme Environmental Impact Statement 3.8 CULTURAL HERITAGE 3.8.1 INTRODUCTION 3.8.1.1 This chapter of the Environmental Impact Statement describes the Cultural Heritage in the existing environment surrounding the proposed development and is divided into the following sub-sections; 3.8 CULTURAL HERITAGE 3.8.1 INTRODUCTION 3.8.2 METHODOLOGY - General - On-Shore Assessment - Off-Shore Assessment - Impact Assessment Methodology 3.8.3 EXISTING ENVIRONMENT - Historical Overview: Newport Town - Historical Overview: The Townlands and Islands - On-Shore Assessment - Off-Shore/Inter-Tidal Assessment 3.8.4 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS - Construction and Operational Phase Impacts - ‘Worst Case Scenario’ Impact - ‘Do-Nothing’ Impact 3.8.5 MITIGATION MEASURES - Construction and Operational Phases 3.8.6 RESIDUAL IMPACTS 3.8.1.2 ÆGIS Archaeology Limited were commissioned to conduct a Cultural Heritage Assessment in September/October 2004 as part of the EIS for the proposed development in Newport. The study included both the proposed development area and the surrounding (on-shore and offshore) environs. The objective of the assessment was to examine the potential impact on the archaeological, architectural and cultural heritage For inspection due to purposes the only.proposed development and to identify mitigation Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. measures where necessary. The report includes a catalogue of known archaeological sites and features in the area and ship wreck data for the region. A copy of the specialist report is included in Volume III of this statement as Appendix 8- Archaeological Impact Assessment . 3.8.1.3 At the request of the Maritime Unit of the National Monuments Section of the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, a preliminary archaeological assessment of the route of the proposed pipeline between Derrinumera landfill and the proposed Newport waste water treatment plant was also undertaken. -

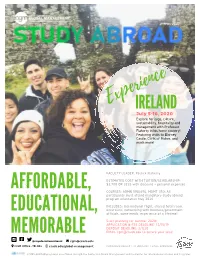

Experience of a Lifetime!

summer 2020 ce rien xpe E IR ELAND July 5-16, 2020 Explore heritage, culture, sustainability, hospitality and management with Professor Flaherty in his home country! Featuring visits to Blarney Castle, Cliffs of Moher, and much more! FACULTY LEADER: Patrick Flaherty ESTIMATED COST WITH TUITION/SCHOLARSHIP: AFFORDABLE, $3,700 OR LESS with discount + personal expenses COURSES: ADMN 590/690, MGMT 350; All participants must attend mandatory study abroad program orientation May 2020 EDUCATIONAL, INCLUDES: International flight, shared hotel room, excursions, networking with business/government officials, some meals, experience of a lifetime! Start planning for summer 2020! APPLICATION & FEE DEADLINE: 12/15/19 MEMORABLE DEPOSIT DEADLINE: 2/1/20 EMAIL [email protected] to secure your seat! @coyotesinternational [email protected] CGM Office : JB 404 csusb.edu/global-management PROGRAMS SUBJECT TO UNIVERSITY FINAL APPROVAL STUDY ABROAD programs are offered through the Center for Global Management and the Center for International Studies and Programs Email: [email protected] http://www.aramfo.org Phone: (303) 900-8004 CSUSB Ireland Travel Course July 5 to 16, 2020 Final Hotels: Hotel Location No. of nights Category Treacys Hotel Waterford 2 nights 3 star Hibernian Hotel Mallow, County Cork 2 nights 3 star Lahinch Golf Hotel County Clare 1 night 4 star Downhill Inn Hotel Ballina, County Mayo 1 night 3 star Athlone Springs Hotel Athlone 1 night 4 star Academy Plaza Hotel Dublin 3 nights 3 star Treacys Hotel, No. 1 Merchants Quay, Waterford city. Rating: 3 Star Website: www.treacyshotelwaterford.com Treacy’s Hotel is located on Waterford’s Quays, overlooking the Suir River. -

Mulranny Tourism Eden Brochure

Ballycastle 5 A MULRANNY TOURISM INITIATIVE TOURISM MULRANNY A 1 R314 Belmullet Excellence of Destination European A R314 N59 R313 R313 R315 Bangor Bellacorick N59 Crossmolina R294 364 Ballina Maumykelly N59 R iv e r R312 M Slieve Carr o y Blacksod Bay 721 600 N26 500 6 400 300 R315 200 B 100 a n W Ballycroy g o e r 627 s t T e Visitor Centre r r a Nephin Beg n Bunaveela i Slievemore l W Lough 311 a 672 y Nephin 806 Lough NATIONAL 700 Conn E 600 Achill Island Glennamong 500 400 688 Lough Keel PARK G 300 Bunacurry INISHBIGGLE 628 200 Acorrymore Lough N Croaghaun ANNAGH 100 ISLAND A 698 R319 Keel R Birreencorragh R312 G W Pontoon 4 714 100 E e Foxford 300 s Lough 200 400 500 600 B ACHILL t e Cullin SOUND r N26 466 G N n I 588 r Lough W R319 e N59 H a Feeagh P a t E y R319 N Buckoogh N58 W / 452 1 e Claggan Mountain B s Knockletragh t a e n r n g Beltra Mulranny o G Lough r European Destination of Excellence r T e r e a n i w l Ballycroy National Park Céide Fields a y R310 Furnace Lough 524 500 Dublin 400 R317 Corraun Hill 300 R312 St Brendens Rockfleet Burrishoole N5 200 Well Castle Abbey Newport Kildownet 100 3 Castle Church W R311 Achillbeg y a e Island s w t n e e r e n r W G Castlebar a n r y e t s R311 e W N59 MAYO t a Clew Bay e r N60 G 1 N5 GREENWAY WESTERN GREAT N84 Clare Island Westport ˜ Jutting proudly into the Atlantic Ocean, Mayo has a stunningly beautiful, unspoilt 7 R330 CO MAYO MAYO CO environment - a magical destination for visitors. -

1St July 2018 REMEMBERING FR PAT BURKE, R.I.P

Parish of Kilmovee Church of the St. Celsus’ Church, Immaculate Kilkelly “A family of families” Conception, Kilmovee St. Patrick’s Church, St. Joseph’s Church Glann Urlaur MISSION STATEMENT he Parish of Kilmovee is a Christian Community, committed to making everyone welcome through meeting in liturgy, prayer and friendship as we bear witness to the love and Tcompassion of Jesus Christ. Fáilte roimh gach éinne. 13th SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME - 1st July 2018 REMEMBERING FR PAT BURKE, R.I.P. I read about your work on the islands off Mayo and how much you enjoyed it. I wondered about you heading off to celebrate Mass and the sacraments on Innisturk and Clare Island or your visits to Caher Island. Your feet, between boat and shore, brought something very special and sacred. I stood at the water’s edge on Lough Derg and watched barefooted men and women walk around me, focusing on their prayers and being pilgrims. Searching for something of Heaven and finding it – I hope and pray. I watched the waters but looked beyond them to people gathering in Westport, to walk past you – not barefooted but broken-hearted, bless themselves and offer a prayer and wonder “why?” I heard them whisper to your parents and your brothers how wonderful you were and how shocked they are. Your loss to them is immeasurable. Certainly you didn’t know the fullness of all you meant to people. I wonder where you are in all of this? I can’t help but believe you believed in the Resurrection you preached to so many and that you are now fully caught up in it.