The Few Weeks of My Life That I Spent in Ireland Were a Wonderful Experience and a Good Beginning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Aspects of the Breeding Biology of the Swifts of County Mayo, Ireland Chris & Lynda Huxley

Some aspects of the breeding biology of the swifts of County Mayo, Ireland Chris & Lynda Huxley 3rd largest Irish county covering 5,585 square kilometers (after Cork and Galway), and with a reputation for being one of the wetter western counties, a total of 1116 wetland sites have been identified in the county. Project Objectives • To investigate the breeding biology of swifts in County Mayo • To assess the impact of weather on parental feeding patterns • To determine the likelihood that inclement weather significantly affects the adults’ ability to rear young • To assess the possibility that low population numbers are a result of weather conditions and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. Town Nest Nest box COMMON SWIFT – COUNTY MAYO - KNOWN STATUS – 2017 Sites Projects Achill Island 0 0 Aghagower 1 0 Balla 1 1 (3) Ballina 49 1 (6) Ballycastle Ballinrobe 28 1 (6) Ballycastle 0 0 0 Ballycroy 0 In 2018 Ballyhaunis ? In 2018 Killala 7 Bangor 0 In 2018 0 Belmullet 0 In 2018 Castle Burke 2 0 Bangor 49 0 Castlebar 37 4 (48) (12) Crossmolina Charlestown 14 1 (6) 8 Claremorris 15 2 (9) (2) Crossmolina Cong 3 1 (6) Crossmolina 8 1 (6) Foxford Foxford 16 1 (12) Achill Island 16 14 0 21 Killala 7 1 (6) 0 Charlestown Kilmaine 2 0 0 0 2 Kiltimagh 6 1 (6) 14 Kinlough Castle 10 0 Mulranny Turlough Kiltimagh 6 Knock 0 0 Louisburgh ? In 2018 40 Balla 1 0 Knock Mulranny 0 0 Newport 14 1 (6) X X = SWIFTS PRESENT 46 1 Aghagower Shrule 10 1 (6) Castle Burke Swinford 21 1 (6) POSSIBLE NEST SITES X 2 15 Tourmakeady 0 0 TO BE IDENTIFIED Turlough 2 In 2018 Westport -

Ideal Homes? Social Change and Domestic Life

IDEAL HOMES? Until now, the ‘home’ as a space within which domestic lives are lived out has been largely ignored by sociologists. Yet the ‘home’ as idea, place and object consumes a large proportion of individuals’ incomes, and occupies their dreams and their leisure time while the absence of a physical home presents a major threat to both society and the homeless themselves. This edited collection provides for the first time an analysis of the space of the ‘home’ and the experiences of home life by writers from a wide range of disciplines, including sociology, criminology, psychology, social policy and anthropology. It covers a range of subjects, including gender roles, different generations’ relationships to home, the changing nature of the family, transition, risk and alternative visions of home. Ideal Homes? provides a fascinating analysis which reveals how both popular images and experiences of home life can produce vital clues as to how society’s members produce and respond to social change. Tony Chapman is Head of Sociology at the University of Teesside. Jenny Hockey is Senior Lecturer in the School of Comparative and Applied Social Sciences, University of Hull. IDEAL HOMES? Social change and domestic life Edited by Tony Chapman and Jenny Hockey London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. © 1999 Selection and editorial matter Tony Chapman and Jenny Hockey; individual chapters, the contributors All rights reserved. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

Eleven Follies in County Offaly

ELEVEN FOLLIES IN COUNTY OFFALY CONDITION SURVEY & MEASURED DRAWINGS October 2013 2 This report was commissioned by Offaly County Council with financial assistance from the Heritage Council to consider the history, significance, condition and conservation of a disparate group of follies and garden building located in County Offaly. The structures range in scale from a pair of small circular stepped plinths, situated in a pond and measuring less than two meters in height, to an impressive eye-catcher rising to over fourteen meters. Most of the structures date from the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries, and some were designed to provide impressive prospects of the surrounding countryside. Surprisingly, for a county that is generally thought to be flat and boggy, Offaly contains a significant number of hills, on which many of these structures are found. With the exception of one earthwork structure, now heavily overgrown and lacking definition, most of the structures survive in a reasonable state of preservation, albeit often in a poor state of repair. While the primary purpose of this report is to illustrate and describe the significance of these structures, and equally important purpose is to recommend practical ways in which there long term future can be preserved, wither by active conservation or by slowing the current rate of decline. The report was prepared by Howley Hayes Architects and is based on site surveys carried out in July and August 2013. 3 4 CONTENTS SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 TOWERS 3.0 GAZEBOS 4.0 EYECATCHERS 5.0 MISCELLANEOUS 6.0 CONCLUSIONS 5 SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS . -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Download Download

FURTHER NOTES ON HUNTLY CASTLE. 137 III. FURTHER NOTE HUNTLN SO Y CASTLE . DOUGLAW Y B . S SIMPSON, M.A., D.LiTT., F.S.A.SCOT. The works of repair, begun in 1923 after Huntly Castle had been hande de lat th ovee y Dukb r f Richmono e Gordod custode dan th o nt y e Ancienoth f t Monuments Departmen s Majesty'Hi f o t s Officf o e Works, havbeew no ne completed e entirth d e an ,castl e ares beeaha n Fig. 1. Huntly Castle : General Plan. cleare e groun f debrith o d d dan s lowere s originait o dt l contourse Th . result has been the discovery of a large amount of additional informa- tion about the development of the fabric and the successive alterations that it has undergone between the thirteenth and the eighteenth centuries. My former account1 thus requires amplification and correction in some important particulars: and I gratefully acknowledge the courteous permission accorded to me by the authorities of H.M. Office of Works to keep in touch with their operations during the past nine years, and discuso t resulte e presensth th n i s t paper.2 1 Proceedings, vol. Ivi. 134-63.pp . I 2hav acknowledgo et e much assistance fro r JamemM s Gregor acteo s wh forema,d a n i n charge during the work, and from Mr Alexander McWilliam, custodian of the castle. The plans 138 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, JANUARY 9, 1933. THE NORMAN EARTHWORKS (see General Plan, fig. 1). -

Crannogs — These Small Man-Made Islands

PART I — INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION Islands attract attention.They sharpen people’s perceptions and create a tension in the landscape. Islands as symbols often create wish-images in the mind, sometimes drawing on the regenerative symbolism of water. This book is not about natural islands, nor is it really about crannogs — these small man-made islands. It is about the people who have used and lived on these crannogs over time.The tradition of island-building seems to have fairly deep roots, perhaps even going back to the Mesolithic, but the traces are not unambiguous.While crannogs in most cases have been understood in utilitarian terms as defended settlements and workshops for the wealthier parts of society, or as fishing platforms, this is not the whole story.I am interested in learning more about them than this.There are many other ways to defend property than to build islands, and there are many easier ways to fish. In this book I would like to explore why island-building made sense to people at different times. I also want to consider how the use of islands affects the way people perceive themselves and their landscape, in line with much contemporary interpretative archaeology,and how people have drawn on the landscape to create and maintain long-term social institutions as well as to bring about change. The book covers a long time-period, from the Mesolithic to the present. However, the geographical scope is narrow. It focuses on the region around Lough Gara in the north-west of Ireland and is built on substantial fieldwork in this area. -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

Route 978 Belmullet to Castlebar

Timetable Route 978 Belmullet to Fares Castlebar FARES Adult Adult Adult Student Student Student Child Child Child Child BAND FTP single return 7-day single day return 7-day single day return 7-day Under 5’s A €2.00 €3.50 €14.00 €1.50 €2.50 €10.00 €1.00 €1.50 €6.00 €0.00 €0.00 B €3.00 €5.00 €20.00 €2.00 €3.50 €14.00 €1.50 €2.50 €10.00 €0.00 €0.00 B C €5.00 €8.50 €34.00 €3.50 €6.00 €24.00 €2.50 €4.00 €16.00 €0.00 €0.00 D €6.00 €10.00 €40.00 €4.00 €7.00 €28.00 €3.00 €5.00 €20.00 €0.00 €0.00 E €7.00 €12.00 €48.00 €5.00 €8.50 €34.00 €3.50 €6.00 €24.00 €0.00 €0.00 F €8.00 €13.00 €52.00 €5.50 €9.00 €36.00 €4.00 €6.50 €26.00 €0.00 €0.00 G €10.00 €15.00 €60.00 €7.00 €11.00 €44.00 €5.00 €7.50 €30.00 €0.00 €0.00 All under 5 year olds are carried free of charge. ADULT FARE STRUCTURE Castlebar Gweesala Mulranny Newport Adult Fare Belmullet Bunnahowen Bangor Erris Ballycroy PO Stephen A Community Doherty's Chamber Structure Chapel Street Post office Centra Post office Garvey Way Centre Filling Station Shop Bus Stop Belmullet Chapel Street €2.00 €2.00 €3.00 €5.00 €7.00 €8.00 €10.00 Bunnahowen Post office €2.00 €3.00 €5.00 €6.00 €8.00 €10.00 Gweesala €2.00 €3.00 €5.00 €7.00 €8.00 Community Centre Bangor Erris Centra €2.00 €3.00 €6.00 €8.00 Ballycroy PO Post office €2.00 €3.00 €6.00 Mulranny Doherty's €2.00 €5.00 Filling Station Newport Chamber Shop €2.00 Castlebar Stephen Garvey Way Bus Stop Mayo Timetable For more information Tel: 094 9005150 978 Belmullet - Castlebar Castlebar - Turlough Museum Email: [email protected] Day: Monday to Saturday Day: Monday to Saturday Web: www.transportforireland.ie/tfi-local-link/ BELMULLET - CASTLEBAR CASTLEBAR - TURLOUGH MUSEUM Operated by: Local Link Mayo, Departs Stops Mon - Sat Departs Stops Mon - Sat Glenpark House, The Mall, Castlebar, Belmullet Chapel Street* 07:00 11:20 Castlebar Rail Station* 13:10 - Co. -

Charlestown Parish Newsletter

CHARLESTOWN PARISH FAMILY MASS: Next Sunday 24th. July is Family Mass Sunday for this month and as I mentioned in last Sunday’s newsletter we are acknowledging St. James, patron of our parish church as NEWSLETTER part of the celebration on that day celebrating the gift of family and the gift of church. Each of us belong to a particular family and all of us belong to the family of God. In baptism we are SIXTEENTH SUNDAY OF ORDINARY TIME 17TH. JULY 2016 born into the family of faith given our Christian name and a very positive direction for life. ——————————————————————————— Family gives us identity and so we are known and recognised as a member of a particular family and SUNDAY MASSES 9.30 am. & 12 noon, Charlestown. 10.30 am., Bushfield. then within that family we receive a name that becomes our very own. There are many different VIGIL MASS 8 pm., Charlestown. names, and within our parish there are quite a few called James and I would like to invite all those to WEEKDAY MASS 10 am. Charlestown. Evening Mass, First Friday only 8 pm., Charlestown. come to the Family Mass on the 24th to celebrate your link with the Parish Church, with faith and the CONFESSION Saturday 2 to 2.30 pm. & 7.30 to 7.55 pm. apostle James, the friend and companion of Jesus. ADORATION Tuesday 10 am. - Friday 11 pm. We have identified twenty families where one or more members bear the name James or Seamus or Jim or Jimmy. I will try to make contact with those families during the week and it would be wonder- Fr. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Fauleens Newport Co. Mayo F28YF77

LUCY HILL - CURRICULUM VITAE Fauleens Newport Co. Mayo F28YF77 086 3599038 [email protected] [email protected] www.lucyhill.ie EDUCATION 2015-present NCAD PhD program, School of Education 1993-94 MFA Winchester School of Art in Barcelona. 1987-90 Crawford College of Art Cork (Painting) 1986-87 NCAD Awards etc. 2018 John Colahan Early Years Artist in Residence - The Ark, Dublin Research Presentation, Wide Eyes International Early Years Conference (Druid Theatre) Galway. Presenter 'Turning Play Inside Out' Early Years Conference, GMIT. 2017 Rosi Braidotti Summer School Utrecht University ‘Posthuman Ethics in the Anthropocene'. Presenter & Plenary panel with Linda Dement & Holly Childs (contemporary Australian artist & poet). Travel and Training Award, The Arts Council. 2016 Thomas Dammann Junior Memorial Award. NCAD Postgraduate Fieldwork research grant. DfES/ Early Childhood Ireland EECERA Conference attendance award. Mayo County Council materials assistance grant. 2013 Linenhall Arts Centre, Children’s Exhibition Commission. 2009 ‘Paperwork’, Public Art Commission, Castlebar Library. 2008 ‘FireEye’, Public Art Commission, Westport Fire Station. 2007 ‘Scaile’, Public Art Commission, Blacksod Pier, Belmullet. 2006 Artist in Residence, Claremorris Open Exhibition. 2005 AIB Art Collection, two paintings purchased. 2003 Terraxicum Officionale’ Public Art Commission, Enniscorthy, Co.Wexford. 2000 Materials Grant, the Arts Council, Dublin. 1998 IMMA, Artists-Work-Program Residency & public talk. 1997 Waterford Regional Hospital, Healing Arts Trust, artist team member. 1996 George Campbell Memorial Travel Award. 1995 Residency, Centre d’Art I Natura, Catalunya. 1994 Aer Rianta Art Collection. 1994 Residency, Cill Reilig Artists Retreat, Ballinskelligs, Co. Kerry. 1992 Materials Grant, the Arts Council, Dublin. 1992 Residency Tyrone Guthrie Centre, Co.Monaghan Exhibitions 2017 Customs House Studios, Westport, Resident Artists Group exhibition. -

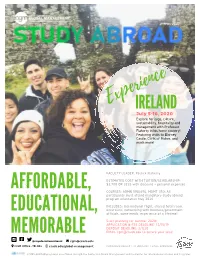

Experience of a Lifetime!

summer 2020 ce rien xpe E IR ELAND July 5-16, 2020 Explore heritage, culture, sustainability, hospitality and management with Professor Flaherty in his home country! Featuring visits to Blarney Castle, Cliffs of Moher, and much more! FACULTY LEADER: Patrick Flaherty ESTIMATED COST WITH TUITION/SCHOLARSHIP: AFFORDABLE, $3,700 OR LESS with discount + personal expenses COURSES: ADMN 590/690, MGMT 350; All participants must attend mandatory study abroad program orientation May 2020 EDUCATIONAL, INCLUDES: International flight, shared hotel room, excursions, networking with business/government officials, some meals, experience of a lifetime! Start planning for summer 2020! APPLICATION & FEE DEADLINE: 12/15/19 MEMORABLE DEPOSIT DEADLINE: 2/1/20 EMAIL [email protected] to secure your seat! @coyotesinternational [email protected] CGM Office : JB 404 csusb.edu/global-management PROGRAMS SUBJECT TO UNIVERSITY FINAL APPROVAL STUDY ABROAD programs are offered through the Center for Global Management and the Center for International Studies and Programs Email: [email protected] http://www.aramfo.org Phone: (303) 900-8004 CSUSB Ireland Travel Course July 5 to 16, 2020 Final Hotels: Hotel Location No. of nights Category Treacys Hotel Waterford 2 nights 3 star Hibernian Hotel Mallow, County Cork 2 nights 3 star Lahinch Golf Hotel County Clare 1 night 4 star Downhill Inn Hotel Ballina, County Mayo 1 night 3 star Athlone Springs Hotel Athlone 1 night 4 star Academy Plaza Hotel Dublin 3 nights 3 star Treacys Hotel, No. 1 Merchants Quay, Waterford city. Rating: 3 Star Website: www.treacyshotelwaterford.com Treacy’s Hotel is located on Waterford’s Quays, overlooking the Suir River.