And She Died …And She Survived Through Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music & Videos by Holocaust

Bearing Witness BEARING WITNESS A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music, and Videos by Holocaust Victims and Survivors PHILIP ROSEN and NINA APFELBAUM Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut ● London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosen, Philip. Bearing witness : a resource guide to literature, poetry, art, music, and videos by Holocaust victims and survivors / Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 0–313–31076–9 (alk. paper) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Personal narratives—Bio-bibliography. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in literature—Bio-bibliography. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in art—Catalogs. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Songs and music—Bibliography—Catalogs. 5. Holocaust,Jewish (1939–1945)—Video catalogs. I. Apfelbaum, Nina. II. Title. Z6374.H6 R67 2002 [D804.3] 016.94053’18—dc21 00–069153 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 2002 by Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00–069153 ISBN: 0–313–31076–9 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Preface vii Historical Background of the Holocaust xi 1 Memoirs, Diaries, and Fiction of the Holocaust 1 2 Poetry of the Holocaust 105 3 Art of the Holocaust 121 4 Music of the Holocaust 165 5 Videos of the Holocaust Experience 183 Index 197 Preface The writers, artists, and musicians whose works are profiled in this re- source guide were selected on the basis of a number of criteria. -

THENEWYORKER.Pdf

A 1940 self-portrait of Salomon (1917-1943), whose autobiographical work “Life? or Theatre?” is an early example of the graphic novel. Courtesy the Jewish Historical Museum © Charlotte Salomon Foundation n February, 1943, eight months before she was murdered in Auschwitz, the I German painter Charlotte Salomon killed her grandfather. Salomon’s grandparents, like many Jews, had !ed Germany in the mid-nineteen-thirties, with a stash of “morphine, opium, and Veronal” to use “when their money ran out.” But Salomon’s crime that morning was not a mercy killing to save the old man from the Nazis; this was entirely personal. It was Herr Doktor Lüdwig Grünwald, not “Herr Hitler,” who, Salomon wrote, “symbolized for me the people I had to resist.” And resist she did. She documented the event in real time, in a thirty-"ve-page letter, most of which has only recently come to light. “I knew where the poison was,” Salomon wrote. “It is acting as I write. Perhaps he is already dead now. Forgive me.” Salomon also describes how she drew a portrait of her grandfather as he expired in front of her, from the “Veronal omelette” she had cooked for him. The ink drawing of a distinguished, wizened man—his head slumped inside the collar of his bathrobe, his eyes closed, his mouth a thin slit nesting inside his voluminous beard—survives. Salomon’s letter is addressed, repeatedly, to her “beloved” Alfred Wolfsohn, for whom she created her work. He never received the missive. Nineteen pages of Salomon’s “confession,” as she called it, were concealed by her family for more than sixty years, the murder excised. -

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION a Project Of

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A project of edited by Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman Remember the Women Institute, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation founded in 1997 and based in New York City, conducts and encourages research and cultural activities that contribute to including women in history. Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel is the founder and executive director. Special emphasis is on women in the context of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Through research and related activities, including this project, the stories of women—from the point of view of women—are made available to be integrated into history and collective memory. This handbook is intended to provide readers with resources for using theatre to memorialize the experiences of women during the Holocaust. Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A Project of Remember the Women Institute By Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman This resource handbook is dedicated to the women whose Holocaust-related stories are known and unknown, told and untold—to those who perished and those who survived. This edition is dedicated to the memory of Nava Semel. ©2019 Remember the Women Institute First digital edition: April 2015 Second digital edition: May 2016 Third digital edition: April 2017 Fourth digital edition: May 2019 Remember the Women Institute 11 Riverside Drive Suite 3RE New York,NY 10023 rememberwomen.org Cover design: Bonnie Greenfield Table of Contents Introduction to the Fourth Edition ............................................................................... 4 By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel, Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute 1. Annotated Bibliographies ....................................................................................... 15 1.1. -

Download a PDF File of the Index for Volume 40

Aindex to Volume 40 – 2018 Compiled by H.e. Knox Z INDEX Index of Authors: books reviewed are listed by author, with the title in italics and the reviewer’s name in brackets, followed by the issue number. Index of Reviewers: books reviewed are listed by reviewer, with the author’s name after the title. Subject Index: the subject is followed by the title and author of the book discussed, with the reviewer’s name in brackets. ‘Corres.’ refers to letters sent to the editor in response to the article listed, and printed in subsequent issues. Index of Original Contributions: all articles which are not strictly book reviews (features, diaries, poems, short stories) are listed here, as well as appearing in the index of authors. Index of Authors Adam, G.: Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Berlin, L.: Cixin Liu: Market in the 21st Century. (Abrahamian, A.A.) 40.9 Evening in Paradise: More Stories. (Lockwood, P.) 40.23 Translator Liu, K. Adams, M.: Ælfred’s Britain: War and Peace in the Viking Age. Welcome Home: A Memoir with Selected Photographs. The Dark Forest. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 (Shippey, T.) 40.9 (Lockwood, P.) 40.23 Death’s End. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 Ahmed, S.: Living a Feminist Life. (Rose, J.) 40.4 Bermant, A.: Margaret Thatcher and the Middle East. The Three-Body Problem. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 Akomfrah, J.: Mimesis: African Soldier. (Harding, J.) 40.23 (Wheatcroft, G.) 40.17 The Wandering Earth. (Richardson, N.) 40.3 Alderton, D.: Everything I Know about Love. -

Summer Seminar for K-12 Educators, Teaching the Holocaust Through

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the current Summer Seminars and Institutes guidelines, which reflect the most recent information and instructions, at https://www.neh.gov/program/summer-seminars-and-institutes-k-12-educators Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Teaching the Holocaust through Visual Culture Institution: Bowdoin College Project Directors: Natasha Goldman Grant Program: Summer Seminars and Institutes (Seminar for K-12 Educators) 400 7th Street, SW, Washington, DC 20024 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 [email protected] www.neh.gov Teaching the Holocaust through Visual Culture Summer Seminar for School Teachers at Bowdoin College Table of Contents Narrative 1 Intellectual Rationale 1 Program -

02-05-2020 Nozze Eve.Indd

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART le nozze di figaro conductor Opera in four acts Cornelius Meister Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte, production Sir Richard Eyre based on the play La Folle Journée, ou Le Mariage de Figaro by Pierre-Augustin set and costume designer Rob Howell Caron de Beaumarchais lighting designer Wednesday, February 5, 2020 Paule Constable 7:30–11:00 PM choreographer Sara Erde revival stage director Jonathon Loy The production of Le Nozze di Figaro was made possible by generous gifts from Mercedes T. Bass, and Jerry and Jane del Missier The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from the Metropolitan Opera Club general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2019–20 SEASON The 503rd Metropolitan Opera performance of WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S le nozze di figaro conductor Cornelius Meister in order of vocal appearance figaro antonio Adam Plachetka Paul Corona susanna barbarina Hanna-Elisabeth Müller Maureen McKay dr. bartolo don curzio Maurizio Muraro Tony Stevenson* marcellina MaryAnn McCormick continuo harpsichord cherubino Howard Watkins* Marianne Crebassa cello David Heiss DEBUT count almaviva Etienne Dupuis don basilio Keith Jameson countess almaviva Anita Hartig Wednesday, February 5, 2020, 7:30–11:00PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene Chorus Master Donald Palumbo from Mozart’s Fight Director Thomas Schall Le Nozze di Figaro Assistant to the Set Designer Rebecca Chippendale Assistant to the Costume Designer Irene Bohan Musical Preparation Howard Watkins*, J. David Jackson, and Katelan Terrell** Assistant Stage Directors Sara Erde, Eric Sean Fogel, and Paula Suozzi Met Titles Sonya Friedman Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes constructed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Das Gewand, Düsseldorf; and Scafati Theatrical Tailors, New York Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses flash effects. -

Wagner&Adaptation-Program Booklet

The Wagner and Adaptation organising team wishes to acknowledge the generous support of the University of Toronto’s Jackman Humanities Institute, the Faculty of Music, the Centre for Comparative Literature, the Department of English, the Munk School of Global Affairs, and the German Department, and of the Canadian Opera Company, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and the German Consulate. Special thanks are owed to Janice Gross Stein (Director, Munk School of Global Affairs), Don McLean (Dean, Faculty of Music), Robert Gibbs (Director, Jackman Humanities Institute), Alan Bewell (Chair, Department of English), Neil ten Kortenaar (Director, Centre for Comparative Literature), Brian Corman (Dean, School of Graduate Studies), John Zilcosky (Chair, German Department), Pia Kleber (Professor of Drama, Wagner and University College), Kim Yates (Associate Director, Jackman Humanities Institute), Gianmarco Segato (Canadian Opera Company), and Sabine Sparwasser (German Consul General). Adaptation Thank you, finally, to all our distinguished presenters for their vital An International Symposium contributions to this event. The Wagner and Adaptation Symposium Team: Caryl Clark (Music), Linda Hutcheon (English and Comparative Literature), Sherry Lee (Music), and Katherine Larson (English), University of Toronto. 31 January - 2 February 2013 Graduate Student Assistants: UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Julia Dolman, Hilary Donaldson, Rebekah Lobosco, and Sean Bellaviti http://www.operaexchange.net/wagner-and-adaptation Wagner and Adaptation – University of Toronto, 31 January – 2 February 2013 Wagner and Adaptation: An International Symposium University of Toronto, 31 January – 2 February 2013 HONOURING LINDA HUTCHEON – PROGRAMME – THURSDAY AFTERNOON, 31 JANUARY JACKMAN HUMANITIES BUILDING, ROOM 100A 3:30 p.m. Welcome and Introduction Robert Gibbs, Director, Jackman Humanities Institute 3:45 p.m. -

Staging Subjectivity Love and Loneliness in the Scene of Painting

Text Matters, Volume 7, Number 7, 2017 DOI: 10.1515/texmat-2017-0007 Griselda Pollock University of Leeds Staging Subjectivity: Love and Loneliness in the Scene of Painting with Charlotte Salomon and Edvard Munch ABSTRACT This paper proposes a conversation between Charlotte Salomon (1917–43) and Edvard Munch that is premised on a reading of Charlotte Salomon’s monumental project of 784 paintings forming a single work Leben? oder Theater? (1941–42) as itself a reading of potentialities for painting, as a staging of subjectivity in the work of Edvard Munch, notably in his as- sembling paintings to form the Frieze of Life. Drawing on both Mieke Bal’s critical concept of “preposterous history” and my own project of “the virtual feminist museum” as a framework for tracing resonances that are never influences or descent in conventional art historical terms, this paper traces creative links between the serial paintings of these two art- ists across the shared thematic of loneliness and psychological extremity mediated by the legacy of Friedrich Nietzsche. Keywords: Edvard Munch, Charlotte Salomon, subjectivity, painting, loneliness, Friedrich Nietzsche. Brought to you by | University of Leeds Authenticated Download Date | 11/1/17 4:48 PM Text Matters, Volume 7, Number 7, 2017 DOI: 10.1515/texmat-2017-0007 Staging Subjectivity It was summer. There were trees and sky and sea. I saw nothing else. Only colours, paintbrush and you, and this. All people became too much for me. I had to go further into solitude, completely away from all people. Then maybe I could find—what I had to find: namely myself: a name for me. -

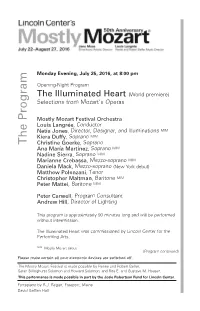

Program Notes

Monday Evening, July 25, 2016, at 8:00 pm m Opening-Night Program a r The Illuminated Heart (World premiere) g Selections from Mozart’s Operas o r P Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra Louis Langrée , Conductor e Netia Jones , Director, Designer, and Illuminations M|M h Kiera Duffy , Soprano M|M T Christine Goerke , Soprano Ana María Martínez , Soprano M|M Nadine Sierra , Soprano M|M Marianne Crebassa , Mezzo-soprano M|M Daniela Mack , Mezzo-soprano (New York debut) Matthew Polenzani , Tenor Christopher Maltman , Baritone M|M Peter Mattei , Baritone M|M Peter Carwell , Program Consultant Andrew Hill , Director of Lighting This program is approximately 90 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. The Illuminated Heart was commissioned by Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. M|M Mostly Mozart debut (Program continued) Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. The Mostly Mozart Festival is made possible by Renée and Robert Belfer, Sarah Billinghurst Solomon and Howard Solomon, and Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Fortepiano by R.J. Regier, Freeport, Maine David Geffen Hall Mostly Mozart Festival Additional support is made possible by Chris and Bruce Crawford, Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz, The Howard Gilman Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc., Charles E. Culpeper Foundation, S.H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation, and Friends of Mostly Mozart. Public support -

Eminist Eriodicals a Current Listing of Contents

WOMEN'S STUDIES LmRARIAN EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 14, NUMBER 4 WINTER 1995 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard Women's Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library / 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS Volume 14, Number 4 Winter 1995 Periodical literature isthe cutting edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodioals: A Current Listing ofContents Is published by the Office ofthe University ofWisconsin System Women's Studies librarian on a quarterly basis with the Intent of Increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It Is our hope that Feminist Periodioals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics In feminist literature; to Increase readers' familiarity with awide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic Information should areaderwlsh to subscribe to ajoumal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from current Issues ofmajorfeministjournals are reproduced In each Issue ofFeminist Periodioals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing ofall journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table ofcontents pages reproduced In each Issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following Information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. subscription prlce(s). 4. Subscription address. 5. Current editor. 6. Editorial address (If different from SUbscription address). -

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters

The Representation of Women in European Holocaust Films: Perpetrators, Victims and Resisters Ingrid Lewis B.A.(Hons), M.A.(Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of PhD June 2015 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Debbie Ging I hereby declare that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copywright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No: 12210142 Date: ii Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to my most beloved parents, Iosefina and Dumitru, and to my sister Cristina I am extremely indebted to my supervisor, Dr. Debbie Ging, for her insightful suggestions and exemplary guidance. Her positive attitude and continuous encouragement throughout this thesis were invaluable. She’s definitely the best supervisor one could ever ask for. I would like to thank the staff from the School of Communications, Dublin City University and especially to the Head of Department, Dr. Pat Brereton. Also special thanks to Dr. Roddy Flynn who was very generous with his time and help in some of the key moments of my PhD. I would like to acknowledge the financial support granted by Laois County Council that made the completion of this PhD possible. -

Griselda Pollock Charlotte Salomon TLS

This is a repository copy of Life? Or Theatre?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/131374/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Pollock, G orcid.org/0000-0002-6752-2554 (2017) Life? Or Theatre? TLS - The Times Literary Supplement (5981). pp. 25-26. ISSN 0307-661X Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Griselda Pollock [email protected] Charlotte Salomon Life? or Theatre? London and New York: Overlook Duckworth 2017 hardcover in a case 840pp, 1,300 colour images, ISBN 9780715652473 £125.00 Includes a translation of the missing pages of the Postscript by Mary Felstiner and Darcy Buerkle. Reprints an essay by Emil Straus from 1963. Charlotte Salomon Life? or Theatre? A Singspiel 1940-42: A Selection of 450 Gouaches Essays by Judith C.E. Belinfante and Evelyn Benesch Berlin: Taschen, 2016 Hardcover, clothbound £30.00 600pp ISBN…… This year marks the centenary of the birth of Charlotte Salomon, the German Jewish artist who was killed in AuschwitZ in 1943 aged twenty-six, a year after she had completed one of the most complex, fascinating and challenging artworks of the modern era. Enigmatically titled Leben?oder Theater?[Life?or Theater?] and comprising 784 paintings of which 330 sport transparent overlays with painted words and musical cues, this single work demonstrates a daZZling variety of painterly modes, from detailed vignettes on a single page to freely painted fields of colour with barely established figures.