Current Theology Notes on Moral Theology: 1979 Richard A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PROCESSIONS in GOD Sr

Teachings of SCTJM - Sr. Rachel Marie Gosda, SCTJM HE IS ALL IN ALL:THE PROCESSIONS IN GOD Sr. Rachel Marie Gosda, SCTJM April 6, 2013 The truth that God is one and also triune has been communicated to us through Divine Revelation. However, the way in which the Church has attempted to explain this great mystery has been the labor of the centuries. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches, “In order to articulate the dogma of the Trinity, the Church had to develop her own terminology with the help of certain notions of philosophical origin: ‘substance’, ‘person’ or ‘hypostasis’, ‘relation’ and so on. In doing this, she did not submit the faith to human wisdom, but gave a new and unprecedented meaning to these terms.”1 The “and so on” indicated here by the Catechism can include one more term, which we shall examine in this reflection: procession. We understand this term to mean the origin of one from another.2 Most of this reflection will deal with the nature and relationship of the two processions which exist in God: that of the Son and the Holy Spirit. In order to arrive at this point, however, let us begin from a more foundational starting-point by considering what exactly “procession” is in God. St. Thomas Aquinas teaches that because God is above all things, anything that we say of Him based on some likeness that we see in creatures is but a representation of who He truly is. Therefore, any comparison that we draw from creatures to God must not be limited to the level of the creature, but must be expanded to the level of the highest creatures, intellectual substances (as God is in the most perfect degree).3 So it is that, although all procession involves some sort of action, this action cannot be considered uniformly between creatures and God. -

The Principle and Foundation of the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius of Loyola and the Jesuit Constitutions1

1536-08_SIS18(2008)_12_Kokkaravalayil 30-10-2008 13:39 Pagina 229 Studies in Spirituality 18, 229-244. doi: 10.2143/SIS.18.0.2033291 doi: © 2008 by Studies in Spirituality. All rights reserved. SUNNY KOKKARAVALAYIL SJ THE PRINCIPLE AND FOUNDATION OF THE SPIRITUAL EXERCISES OF ST IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA AND THE JESUIT CONSTITUTIONS1 SUMMARY — The Principle and Foundation (PF) of the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius (n. 23) puts in a nutshell the theme of the whole Spiritual Exercises, which includes the final end of human beings and the right attitude to reach that. According to PF, we, human beings are created to praise, reverence and serve God by means of which our souls are saved. The other things are created to help us to reach our goal. We are to use the other creatures in so far as they help us to achieve our end. Such a use requires of us an attitude of indifference toward all created things and the choice of that which is more conducive to attain our goal. This theme is not limited to the Spiritual Exercises, but pervades other writings of its author. In this article we enquire how far this theme is present in the Jesuit Constitutions, and whether PF can provide a key to a better understanding of the Constitutions. We find that the Jesuit Constitutions, besides referring numerous times to the terms typical of PF, are charged with the spirit of PF. The content of PF, which can appear to be an abstract spiritual principle, is weaved into the Constitutions to be lived in the day-to-day life of a Jesuit. -

The Extraordinary Synod - a Summary

Volume 9, Number 2 Fellowship of Catholic Scholars Newsletter March 1986 The Extraordinary Synod - A Summary [Editor'sNote: Three members of the Fellowship's Executive Board attended the ExtraordinarySynod, held in Rome, November 25th-December 8th, 1985. The insights of Fr. Kenneth Baker, S.J., Fr. Michael Wrenn, and Professor Ralph Mcinerney follow. Mr. Robert DiVeroli is a syndicated columnist for several West Coast daily newspapers.] The Synod interpreted Vatican IIin a particular way-in three documents. First,the message to the world'sfaithfulproposes the Church as the Body of Christ withthe faithfulcalled upon to place themselves . in communion with this Church (Lumen Gentium), . as hearers of God's Word (Dei Verbum), . participating in the holy liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium) , . and serviceable to mankind, especially to the poor (Gaudium et Spes). Notice the hierarchy of values. Secondly, "The Final Report"celebrated and confirmed the Second Vatican Council on its 20th anniversary. The participating bishops experienced, what they called, "communion in one spirit, the one faith and hope, and in the one Catholic Church." Unanimously, they willed to translate that Council into the life of the Church. But they also admitted the estrangement going on in the "First World" and the paradox of a faith enriched by Vatican II in places where people are oppressed. The Synod spoke, too, of the temptation of consumerism and the misreading of Council documents to explain "shadows in the Council's reception." . Too much renewal identified with external structures and too little with God. The pastoral charactor of the Council documents cannot be separated from their doctrinal vigor. -

C:\Users\User\Documents\Parish

1, 2, and 3 John, John Painter (Sacra Pagina) A simple path, Teresa, Mother Above all a shepherd, Ugo Groppi and Julius Lombardi Acts of the Apostles, Luke Timothy Johnson An Adult Christ at Christmas : essays on the three Biblical Christmas stories, Raymond Brown Apparitions of Our Lady at Medjugorje: An historical account …Kraljevic, Svetozar Babylon, Joan Oates Beauty at dawn: Notes to my sisters, Paula Bendry Larsen Birth of Messiah : a commentary on infancy narratives in gospels of Matthew and Luke, Raymond Brown Catholic matters: Confusion, Richard John Neuhaus Christ actually: The son of God for the secular age, James Carroll Christian ministry in Priesthood: A history of the ordained ministry in the Roman Catholic Church, Kenan Osborne Christian sacraments of initiation: Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist, Kenan Osborne Christology as narrative quest, Michael Cook Church and community in crisis: The Gospel according to Matthew, J. Andrew Overman Churches the apostles left behind, Raymond E. Brown City of God, Saint Augustine Civilizations of the Holy Land, Paul Johnson Colossians and Ephesians, Margaret MacDonald Community of the Beloved Disciple: The life, loves, and hates of an individual church in New Testament times, Rayond Brown Consider Jesus: Waves of renewal in Christology, Elizabeth Johnson Cross & human transformation: Paul’s apocalyptic word in 1 Corinthians, Alexandra Brown Crossing the threshold of hope, Pope John Paul II Crucified Christ in Holy Week, Raymond E. Brown Daily life in the time of Jesus , Henri Daniel-Rops -

Courses & Curricula

Australian Religion Studies Review 61 Courses & Curricula Religious Ed~ation in the UK: A View from Down Under "Bitter blow for Church School", "The the U.K. covered both denominational and National Curriculum will damage every non-denoininational institutions and so the child's education", "Parental voices raised following thoughts need not be seen as . against Kenneth Baker's 'Shake Up"', one-eyed or sectarian. "Baker, architect of the second . It may be wise for me to attempt to Reformation", "Health attacks 'confidence 'define' Religious Education as I perceive trick' on parents". it. Since Terry Lovat in his recent book, These and many other similar comments "What is This Thing Called Religious were circulating in the United Kingdom Education?" maintains that educational press and media during the latter part of and theological developments have my sabbatical of eighteen months in 1987/ worked together to change the Religious 88. They apply to Kenneth Baker's Education agenda once and for all, the task proposal to introduce a National . of defining such a life-long work could. Curriculum in 1989. The first comment take a whole paper in itself. For the (from The Universe) focuses on one aspect purpose of this article let it suffice to say of Kenneth Baker's 'Second reformation' that most of what I see RE to be can be viz. the implications for Religious activity engaged in by both teacher and Education. Since the purpose of my pupil which hopes to free people from Sabbatical in the U.K. was to visit ignorance, prejudice and an over education institutions and to look at RE, its dependence on an emotional response to academic and curriculum aspects, I will life's events. -

Ewtn - Mother Angelica Cd Title Cd

1 EWTN - MOTHER ANGELICA CD TITLE CD # 2 Corinthians 3:18 MC258 A few thoughts on many things MC157 A little child shall lead them MC142 A little child shall lead them MC293 A sign from heaven MC188 A sign from heaven MC227 A trip to South America MC130 A viewer's poem MC160 Abraham MC238 Act of contrition MC305 Advent MC117 All Saints - Halloween MC186 An informed conscience MC178 Angels MC111 Angels MC280 Anger MC101 Anima Christi MC289 Another look at mortification MC271 Answers for your non-Catholic friends with Bruce Sullivan & Fr. Luther T222 Ash Wednesday & Lent MC199 Assumption & Anniversaries MC175 Bad things happen MC286 Blessed Gianna Beretta Molla with Joe Cunningham T322 Blindness MC297 Blueprint for life MC287 Catholics epistles MC288 Christmas MC244 Christmas message MC192 Christmas: What is your spirit of Christmas? MC292 Christmas: What will you give Christ for Christmas? MC193 Christmas: What will you give Christ for Christmas? MC243 Compassion MC247 Compassion & forgivenss MC210 Conscience MC212 Consequences of sin MC 148 Consequences of sin MC276 Conversion MC128 Death & Dying MC205 Degrees of glory MC211 Degrees of glory MC221 Develop an informed conscience MC05 Developing an informed conscience MC230 Devotion MC315 Devotion to the Holy Angels with Fr. Wagner & Fr. Nortz T365 Difficult parables MC134 Difficult parables MC266 Disappointment MC104 Disappointment MC207 2 Do not let your hearts be troubles MC194 Do you know God? MC149 Do You know God? MC167 Do You know God? MC381 Dreams of St. John Bosco MC197 Enemies -

Solidarity According to the Thought of Fr. Pedro Arrupe and Its Application to Jesuit Higher Education Today James Menkhaus

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2013 Solidarity According to the Thought of Fr. Pedro Arrupe and Its Application to Jesuit Higher Education Today James Menkhaus Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Menkhaus, J. (2013). Solidarity According to the Thought of Fr. Pedro Arrupe and Its Application to Jesuit Higher Education Today (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/922 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOLIDARITY ACCORDING TO THE THOUGHT OF FR. PEDRO ARRUPE AND ITS APPLICATION TO JESUIT HIGHER EDUCATION TODAY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By James Menkhaus May 2013 Copyright by James Menkhaus 2013 SOLIDARITY ACCORDING TO THE THOUGHT OF FR. PEDRO ARRUPE AND ITS APPLICATION TO JESUIT HIGHER EDUCATION TODAY By James Menkhaus Approved March 26, 2013 ________________________________ ________________________________ James Bailey, Ph.D. Anna Scheid, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Assistant Professor of Theology (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ Dan Scheid, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Theology (Committee Member) _________________________________ ________________________________ James C. Swindal, Ph.D. Maureen O‘Brien, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty Graduate School Chair, Department of Theology Of Liberal Arts Professor of Theology Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY ACCORDING TO THE THOUGHT OF FR. -

Offering a Fragrant Holocaust: a Priesthood of Encounter and Kenosis

Offering a fragrant holocaust: A priesthood of encounter and kenosis Author: Wing Seng Leon Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108279 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2018 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Offering a Fragrant Holocaust: A Priesthood of Encounter and Kenosis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Licentiate in Sacred Theology (S.T.L.) degree from the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry By (Jerome) Wing Seng Leon, SJ Supervisor: Prof. John Baldovin, SJ Reader: Prof. Thomas Stegman, SJ August 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Priesthood and the Society of Jesus ............................................................................................ 1 Objectives of this Thesis ............................................................................................................. 4 History............................................................................................................................................. 7 The Church, the Priesthood and the Estrangement in the Early Modern Period ........................ 8 Ignatius of Loyola and the Foundations of the Order ............................................................... 14 Preti Reformati – The Orders of Clerk -

St. Cletus Canticle PASTORAL STAFF Paulette Bolton 600 W

PARISH STAFF REV. ROBERT CLARK Pastor REV. EDGAR RODRIGUEZ Associate Pastor REV. KENNETH BAKER Associate Pastor REV. CHARLES GALLAGHER Pastor Emeritus REV. RON ANGLIM Weekend Associate REV. MR. JESÚS & SILVIA CASAS Deacon Couple REV. MR. STUART & MARLENE HEYES Deacon Couple St. Cletus Canticle PASTORAL STAFF Paulette Bolton 600 W. 55th Street - La Grange, IL Worship (708) 352-6209 Rectory (708) 215-5422 Deacon Jesús Casas (708) 352-4820 School Hispanic Ministry www.stcletusparish.com (708) 215-5440 June 10, 2012 Kristen Maxwell Youth Ministry (708) 215-5419 Feast of Corpus Christi Mary Beth Ford Social Concerns (708) 215-5418 Debbie Lestarczyk Business Manager (708) 215-5405 Justin Sisul Music Ministry (708) 215-5423 Christopher Wagner Technology (708) 215-5420 Deacon Stuart Heyes Ministry of Care (708) 215-5407 SCHOOL STAFF Jeff Taylor School Principal Kathy Lifka Assistant Principal Mary Lee Krieger Secretary Jeannie Scalzitti Receptionist/Office Assistant (708) 352-4820 RELIGIOUS EDUCATION STAFF Sr. Pat McKee Director of Religious Education Holly Kallal Secretary (708) 352-2383 RECTORY STAFF All are welcome. Patricia Drobny Handicapped parking is located in front of church. Bulletin Editor/Office Assistant Bobbie Kallal Personal hearing devices are available from the ushers/greeters. Human Resources Mary Zwolinski Children’s Chapel available for the young and the restless Parish Accounting in the rear of the church. (708) 352-6209 Page Two Feast of Corpus Christi June 10, 2012 Mass Intentions for the Week of June 11 - June 17, 2012 Day Time Intentions Monday 8:00 a.m. John Hopp Tuesday 8:00 a.m. Purgatorial Society Wednesday 8:00 a.m. -

What Magis Really Means and Why It Matters

Geger: What Magis Really Means What Magis Really Means and Why It Matters Fr. Barton T. Geger, SJ Regis University ([email protected]) Abstract Many definitions of the magis are proffered in Jesuit circles, not all of which are clear or helpful. The best definition, in terms of practicality, fidelity to the sources, and correspondence to other Ignatian themes, is “the more universal good.” It is closely linked to the unofficial motto of the Society of Jesus, “For the Greater Glory of God.” I. The Problem therefore, all should be allowed to illuminate the dynamic character of the Ignatian “more.” In the No term appears more popular in the parlance of same vein, if a wide variety of texts are cited to Jesuit institutions today than the magis. Originally a explain the magis -- everything from the tales of Latin adverb that meant “more” or “to a greater chivalry that Ignatius read as a youth to the Ratio degree,” it is now commonly used as a proper Studiorum, a manual for Jesuit schools written forty noun to denote a key element of Ignatian years after the saint’s death -- it only shows how spirituality. Especially in Jesuit schools, “Magis deeply the magis permeated Ignatius’ spirituality. Student Groups,” “Magis Classes,” “Magis Retreats,” “Magis Scholarships,” “Magis Auctions,” Unfortunately, however, the variety of definitions “Magis Institutes” and “Magis Committees” are cannot be justified so easily, for at least four ubiquitous. The term appears in official decrees of reasons. First, if anecdotal evidence is any General Congregations of the Society of Jesus, indication, ambiguity about the magis can breed and also in the writings and allocutions of Jesuit confusion and guilt among Jesuits and their Superiors General. -

Share 2013 Spring

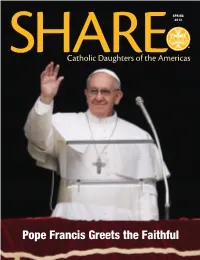

SPRING 2013 ® SHARECatholic Daughters of the Americas Pope Francis Greets the Faithful “ My prayer for you is that God will deeply bless you throughout your retreat year as you mother your children on the straight and narrow path that leads to heaven.” — Donna-Marie Cooper O’Boyle 5-Minute Retreats for Every Day of the Year Catholic Mom’s Café Being a mom is not for the faint of heart. is collection of quick, “mini- retreats for moms” will energize you and help you nd the faith, hope, and love you need to be a great Catholic mom— while growing closer to Christ every day. KINDLE & NOOK ID# T1272 $14.95 VERSIONS AVAILABLE! The Power of Prayer New Inspiration Enrich Daily Life Cultivate the same virtues as Saint Catholic women are facing unprec- is deeply theological, yet approach- Monica did during her long wait for edented questions about sex, money, able text answers many questions God’s answer for her child. Includes marriage, work, children, and the about prayer to draw readers closer 18 contemporary re ections and Church itself. Empower yourself to God through Christ. meditations from Saint Augustine. with the answers they found. ID# T1413 $19.95 A33BBQ63 ID# T1261 $12.95 ID# T1371 $16.95 Scan code for Catholic books up Call to order: to 75% off! 1-800-348-2440 www.osv.com 829300_ShareMag_Mar2013.indd 1 3/13/13 9:09 AM National Regent’s Message A Time for Renewal Dear Daughters, Spring is coming! Spring is coming! I hope, I hope I hope! Spring brings a renewed energy to the earth, and it also gives us a boost. -

Parish Directory

THE ARCHDIOCESE OF CHICAGO PARISH DIRECTORY MAY 2021 Administrative 1 Renew My Church: New Parishes 2 Parishes 5 Missions 83 Shrines, Chaplaincies, Oratories 86 Priests 90 Active, Inactive, and Retired Priests 125 by Ordination Class Extern Priests 131 Deacons 136 Active and Retired Deacons 159 by Ordination Class Lay Ecclesial Ministers 164 Administrative (as of September 21, 2020) Cardinal Blase J. Cupich Archbishop of Chicago PO Box 1979 Chicago, IL 60690-1979 Tel: (312) 534-8230 Fax: (312) 534-6379 Vicar General Most Rev. Robert G. Casey PO Box 1979 Chicago, IL 60690-1979 Phone: (312) 534-8271 Fax: (312) 534-6379 Cindilynn Dammann, Administrative Assistant Vicariate I Vicariate IV Most Rev. Jeff rey S. Grob Most Rev. John R. Manz Episcopal Vicar Episcopal Vicar 200 N Milwaukee Ave #200 1400 South Austin Blvd Libertyville, IL 60048-2250 Cicero, IL 60804 (847) 549-0160 (708) 329-4040 Karen Gorajski, Administrative Assistant Elizabeth Ceisel-Mikowska, Administrative Assistant Vicariate II Vicariate V Most Rev. Mark A. Bartosic Most Rev. Andrew P. Wypych Episcopal Vicar Episcopal Vicar 1641 W. Diversey Pkwy. 2330 W 118th St Chicago, IL 60614 Chicago, IL 60643 (773) 388-8670 (312) 534-5050 Judith Keefe, Administrative Assistant Elsa Svelnys, Administrative Assistant Vicariate III Vicariate VI Most Rev. Robert Lombardo, CFR Most Rev. Joseph N. Perry Episcopal Vicar Episcopal Vicar 1850 S. Throop St. Cardinal Meyer Center Chicago, IL 60608 3525 S. Lake Park Ave. (312) 243-4655 Chicago, IL 60653-1402 Gloria Alcala, Administrative Assistant (312) 534-8376 Deacon Dan Ragonese, Administrative Assistant Most Rev. Kevin M. Birmingham Director, Parish Vitality and Mission 1 The following former parishes were united through the Renew My Church planning process and are part of a new or existing parish.