ASCAP at 100 545 ASCAP at 100

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year 1. Summer 1. Your Imagination

Your Imagination – Year 1 Summer 1 Key vocabulary Pulse A single vibration or short burst of sound, electric current, light, Relevant Songs Singing Tips or other wave. Daydream Believer Ensemble A group of musicians who perform together. This song was released in 1968 by The Monkees. It is a Rock song Pitch How high or low the music sounds. and it reached No. 1 in the US on its release. Rhythm A strong, regular repeated pattern of movement or sound. A Whole New World Call and A series of two parts usually This song is from the 1992 Warming up by singing notes of Response played or sung by different musical movie, ‘Aladdin’. It was different pitches before singing musicians. The second part is helps protect our voices. written by Alan Menken and Tim heard as a comment about or an Standing up straight helps us to Rice. It has been covered many answer to what the first has project our voices. times by different artists over the Shouting could hurt our voices. sung. This mimics or makes fun of years. Singing the words loudly and how people talk back and forth Rainbow Connection clearly mean people can hear to each other. and enjoy our songs. Repetition Something happens over and Breathing in before the start of This is a song from the 1979 film over again. each line helps us sing with ‘The Muppet Movie’. It was control. Tempo How fast or slow the music is. written by Paul Williams and Dynamics How loud or quiet the music is. -

The Commencement Exercises of the Academic Year 2020–21 Dickinson

The Commencement Exercises of the Academic Year 2020–21 Dickinson College Sunday, May 23, 2021 Two O’clock The Commencement Exercises he first Dickinson College Commencement exercises were held Clerical gowns were worn by the earliest faculty but disappeared T in the Presbyterian church on the town square, and the occasion early in the 19th century. Curiously, students at Dickinson adopted was something of a public holiday. Professors and students marched the academic robes at Commencement before faculty, who did not in procession, first from the college buildings in Liberty Alley and appear in gown and hood until the procession of 1904. Previous then from our present campus. Each graduate gave proof of his generations of graduating seniors were distinguished only by their learning by delivering an address in Latin or English, a practice that affiliation with one of the literary societies—the red rose of Belles continued through most of the 19th century. In later years, music was Lettres or the white rose of Union Philosophical. During today’s introduced as a restorative between orations, and as the number of ceremony, graduating seniors who studied abroad during their graduates increased, the final oratory was reduced to one guest Dickinson careers wear the flags of their host countries on their speaker, rewarded with an honorary doctorate. academic gowns. The gowns worn by participants hearken back to the monastic In the college’s early days, a Latin ritual was included in the robes of the Middle Ages. The hood—worn by clergy and students Commencement ceremony, beginning with an inquiry by the for warmth in drafty halls—was retained in specialized cases, such president to the trustees: “Placetne vobis, viri admodum generosi, ut as academic distinction. -

Quintet/String Orchestra Repertoire

Millington Strings Quintet Repertoire 2019 Title Composer A Chloris Reynaldo Hahn A Summer Place Percy Faith/Max Steiner A Thousand Years Hodges/Perri Adagietto fr Symphony # 5 Gustav Mahler Adagio Tomaso Albinoni Adagio Cantabile Ludwig van Beethoven Agnus Dei Johann Sebastian Bach Air (fr 2nd French Suite) Johann Sebastian Bach Air (fr Water Music) Georg Friedrich Handel Air (On The G String) Johann Sebastian Bach All Hail to Thee Ingemar Braennstroem All I Ask Of You Andrew Lloyd-Webber All I Want Is You Bono All You Need Is Love John Lennon/Paul McCartney Amazing Grace English/American Traditional Americana Suite, Mvt 1: 400 HP, Heavy Foot Stephen H Millington Americana Suite, Mvt 2: Foxy Stephen H Millington Americana Suite, Mvt 3: Starry Night, Starry Eyes Stephen H Millington Americana Suite, Mvt 4: Aretha Stephen H Millington And I Love Her John Lennon/Paul McCartney And So It Goes Billy Joel Andante (fr Water Music) Georg Friedrich Handel Andante Festivo Jean Sibelius Ang Tangi Kong Pag-Ibig Constancio de Guzman Anitra's Dance Edvard Grieg Aniversary Waltz Dave Franklin/Al Dubin April In Portugal Raul Ferrao Aria sopra la Bergamasca Marco Uccellini Tuesday, August 6, 2019 Page 1 of 14 Title Composer Arioso Johann Sebastian Bach Asher Bara Israeli Traditional Asher Boro Israeli Traditional Ashokan Farewell Jay Ungar At Last Mack Gordon/Harry Warren Ave Maria Johann Sebastian Bach/Charles Gounod Ave Maria Franz Schubert Bachianas # 5 Heitor Villa-Lobos Badinerie Johann Sebastian Bach Ballade Ciprian Porumbescu Be Thou My Vision -

National Will to Fight: Why Some States Keep Fighting and Others Don't

C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL WILL to FIGHT Why Some States Keep Fighting and Others Don’t Michael J. McNerney, Ben Connable, S. Rebecca Zimmerman, Natasha Lander, Marek N. Posard, Jasen J. Castillo, Dan Madden, Ilana Blum, Aaron Frank, Benjamin J. Fernandes, In Hyo Seol, Christopher Paul, Andrew Parasiliti For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2477 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0053-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Landing ships putting cargo ashore on Omaha Beach, mid-June, 1944/Photograph 26-G 2517 from the U.S. Coast Guard Collection in the U.S. National Archives. Cover design by Eileen Delson La Russo Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. -

2020 Recital- Costume Details

2020 Recital- Costume Details Class Song Artist Costume Description Hair Tights Style/Color Shoes Adult Adv Tap Another One Bites the Queen Black blazer with silver sparkle Low ponytail N/A Black tap shoes Dust sleeves, no tights Adult Beg/Inter Tap War James Horner Blue dress Low ponytail Light suntan Black tap shoes convertible Adult Beg/Inter Ballet Rewrite the Stars Zendaya and Zac Efron performed by Teal dress Low ponytail Light suntan Pink ballet shoes The Piano Guys convertible Adult Hip Hop Ladies through the Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Black pants, sparkly tank top High ponytail N/A Black sneakers/jazz shoes decades Rhianna and Lizzo (Multi) with black tank top underneath. Long black socks, tank, no tights Adult Inter/Adv Jazz 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters Sequin dress with attached High ponytail Light suntan stirrup Half sole biketard Adult Modern Westworld Ramin Djawadi Multi: Black Cape (all) 3: Blue and Low ponytail Light suntan stirrup Half sole white unitard: (2): skirt with white top. Alegria Dance Company Yellow Coldplay performed by Brittin Lane Yellow dress with a black leotard Low parted ponytail Light suntan stirrup Half sole under Alegria Dance Company Your Peace Will Make Us Audrey Assad Featuring Urban Nude dress with black leotard Low parted ponytail Light suntan stirrup Half sole One Doxology under Ballet 2/3 Kingdom Dance Alan Menken from the Tangled Purple and pink tutu Half up half down Ballet pink convertible Pink canvas ballet shoes soundtrack tights Ballet 4 December Tchaikovsky Emerald green euro tutu -

South Carolina Band Directors Association 2017 Jazz Festival Repertoire

South Carolina Band Directors Association 2017 Jazz Festival Repertoire Camden Middle School – Nancy Neal Domino – Van Morrison, arr. Mike Story Bad Attitude – Michael Sweeney Mustang Sally – Bonny Rice, arr. Victor Lopez Crayton Middle School – Daryl Byrd Broadway – Bobby Bird, Teddy McRae, & Henry Woode, arr. George Vincent Li’l Darlin’ – Neal Hefti, arr. Roy Phillippe Crank It Up – Patrick Broadbent Gaffney Middle School Jazz Band – Elliott W. Rawls Mercy, Mercy, Mercy – Mike Story The Wayfaring Stranger – Mike Collins-Dowden It Is What It Is – Victor Lopez Gettys Middle School – Joey Finley Sesame Street – Joe Reyoso, arr. John Berry Imagine – John Lennon, arr. John Berry The Funky Monkey – Rick Stitzel Hartsville Middle School Jazz Ensemble – Marlin T. Ketter Ants in the Pants – George Vincent I’ll Be There – arr. Paul Murtha In The Zone! – Rick Stitzel Honea Path Middle School Jazz Ensemble – Ms. Sara R. Glogowski Bari Bari Good – Andy Clark Yesterday – The Beatles, arr. Rick Stitzel 25 or 6 to 4 – Chicago, arr. Paul Murtha JET Middle School Jazz Ambassadors – Angelyn Dorn St. James Infirmary – Joe Primrose Jive Samba – Nat Adderley Blues By Five – Red Garland Marlboro School of Discovery Jazz Band – Patrick Davis Take the “A” Train – Billy Stayhorn Attitude Adjustment – Larry Barton Gonna Fly Now – Bill Conti, Ayn Robbins, & Carol Connors Powdersville Middle School Jazz Ensemble – Chris Mitchell Ja-Da – Bob Carleton, arr. Michael Sweency Peter Gunn – Henry Mancini, arr. Mike Lewis Sangaree Middle School Jazz Band – Brian Trauger Bye Bye Blackbird – Mort Dixon & Ray Henderson, arr. Mark Taylor What a Wonderful World – George David Weiss & Bob Thick, arr. -

Matematiska Vetenskaper Årsberättelse 2015 Matematiska Vetenskaper Årsberättelse 2015

Matematiska vetenskaper Årsberättelse 2015 Matematiska vetenskaper Årsberättelse 2015 Redaktör: Setta Aspström Tryckning: Chalmers reproservice och vaktmästeriet Matematiska vetenskaper Omslag: Mattesupporten. Sedan år 2006 har studenter på Chalmers och Natur- vetenskapliga fakulteten kunnat vända sig till Mattesupporten för att få hjälp med matteproblem i sina kurser. Supporten äger rum på kvällstid några gånger i veckan på Chalmers bibliotek, både på Johanneberg och Lindholmen, och bemannas huvudsakligen av amanuenser vid avdelning Matematik. Verksam- heten stödjs ekonomiskt både av Chalmers centralt och av Naturvetenskapliga fakulteten, Göteborgs universitet. Foto: Setta Aspström Adress: Matematiska vetenskaper Chalmers tekniska högskola och Göteborgs universitet 412 96 Göteborg www.chalmers.se/math eller www.math.gu.se Årsberättelse 2015 Entrén på Chalmers tvärgata 3 när vintern slår till Matematiska vetenskaper Chalmers tekniska högskola och Göteborgs universitet 412 96 Göteborg Göteborg, februari 2016 Innehållsförteckning Organisation och personal Matematiska vetenskaper 3 Matematik 4 Matematisk statistik 6 Centrum för grundläggande vetenskaper 7 Verksamhetsstöd 8 Personal 12 Utbildning Grundutbildning Göteborgs universitet 18 Grundutbildning Chalmers tekniska högskola 24 Forskarutbildning 29 Forskning Forskargrupper och seminarieserier 32 Publikationer 51 Konferenser 66 Gäster och gästforskning 75 Samverkan Mötesplats matematik 78 Matematik- och statistikkonsulterna 79 Projekt 80 Uppdrag 82 Populärvetenskap 85 Ekonomisk rapport Resultaträkning 87 2 Matematiska vetenskaper I den här årsberättelsen kan vi läsa att 2015 var ett bra år för Matematiska vetenskaper, inom hela vår verksamhet. Vår forskning har resulterat i fl er publicerade artiklar än tidigare, och tack vare fl era bidrag från både Vetenskapsrådet, Wallenbergstiftelserna och andra bidragsgivare har vi kunnat bjuda in många internationella fors- kare på alla nivåer, från postdok till professor, som på olika sätt bidragit till vår forskningsmiljö. -

Strings / Violin Instruction

strings 122 Sevcik Studies for Strings 123 Violin Methods by G. Schirmer, Inc. 124 All Strings 124 Orchestra Play-Along 124 Violin 124 Instruction & Technique 129 Songbooks & Repertoire 128 Violin Play-Along Series 133 Easy Concertos & Concertinos Series 134 Solos 134 Duets 134 Quartets 135 Viola 135 Instruction & Technique 135 Songbooks 135 Solos 136 Cello 136 Instruction & Technique 137 Songbooks & Repertoire 139 Solos 139 Duets 139 Quartets 139 Bass 139 Harp hal 140 String Ensembles 140 Duets 140 Trios 140 Quartets 140 Quintets 140 Ensembles 140 Pop Specials for String Quartets 2011 141 Strings Charts Series 122 SEVCIK STUDIES FOR STRINGS Bosworth Since 1901, Otakar Sevcik’s works have formed the basis of many schools of string playing around the world. Thousands of players continue to find Sevcik an invaluable aid to technical development. In practicing Sevcik – as in playing scales, etudes, or pieces – there are always four main headings to consider: purity of intonation, evenness of tone, exactness of rhythm and physical freedom and ease. This series of books is designed for the beginning student to improve all areas of technique. Each book contains numerous exercises and melodies. VIOLIN SEVCIK VIOLIN SEVCIK VIOLIN SEVCIK VIOLIN Studies – OPUS 6 Studies – OPUS 8 Studies – OpUS 1 VIOLIN METHOD FOR BEGINNERS CHANGES OF POSITION AND PREPARATORY SCALE STUDIES SCHOOL OF VIOLIN TECHNIQUE A compendium of studies for changes of positions with preparatory scale studies. One of the unique advantages of the shifting exercises in Sevcik’s Opus 8 is that they provide a musical framework within which to place PART 3 each shift. -

Jane Monheit the Lovers, the Dreamers and Me Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jane Monheit The Lovers, The Dreamers And Me mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Lovers, The Dreamers And Me Country: Europe Released: 2008 Style: Contemporary Jazz, Vocal MP3 version RAR size: 1115 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1908 mb WMA version RAR size: 1822 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 640 Other Formats: MP2 APE AA RA XM VOX MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Like A Star 1 5:15 Written-By – Corinne Bailey Rae Something Cool 2 4:56 Written-By – William C. Barnes* Slow Like Honey 3 5:58 Written-By – Fiona Apple This Girl's In Love With You 4 4:56 Written-By – Burt Bacharach-Hal David* I'm Glad There Is You 5 5:08 Guitar – Frank VignolaWritten-By – Jimmy Dorsey, Paul Mertz* Get Out Of Town 6 3:40 Tenor Saxophone – Seamus BlakeWritten-By – Cole Porter I Do It For Your Love 7 4:04 Written-By – Paul Simon I Ain't Gonna Let You Break My Heart 8 5:21 Written-By – David Eldon Lasley*, Julie Ann Lasley* Ballad Of The Sad Young Men 9 6:01 Written-By – Frances Landesman*, Thomas J. Wolf, Jr.* No Tomorrow (Acaso) 10 5:12 Written-By – Abel Ferreira Da Silva*, Ivan Lins, Peter Eldridge Lucky To Be Me 11 5:26 Written-By – Adolph Green, Betty Comden, Leonard Bernstein A Primeira Vez 12 3:03 Written-By – Armando Marcal*, Bide Rainbow Connection 13 4:09 Written-By – Kenneth Ascher*, Paul Williams Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Concord Music Group, Inc. Copyright (c) – Concord Music Group, Inc. -

True Films 3.0

TRUE FILMS 3.0 This is the golden age of documentaries. Inexpensive equipment, new methods of distribution, and a very eager audi- ence have all launched a renaissance in non-fiction film making and viewing. The very best of these non-fiction films are as entertaining as the best Hol- lywood blockbusters. Because they are true, their storylines seem fresh with authentic plot twists, real characters, and truth stranger than fiction. Most true films are solidly informative, and a few are genuinely useful like a tool. The rise of documentaries and true cinema is felt not only in movie theaters, but on network TV and cable channels as well. Reality TV, non-fiction stations like the History Channel or Discovery, and BBC imports have increased the choices in true films tremendously. There’s no time to watch them all, and little guidance to what’s great. In this book I offer 200+ great true films. I define true films as documentaries, educational films, instructional how-to’s, and what the British call factuals – a non-fiction visual account. These 200 are the best non-fiction films I’ve found for general interest. I’ve watched all these films more than once. Sometimes thrice. I haven’t had TV for 20 years, so I’ve concentrated my viewing time on documentaries and true films. I run a little website (www.truefilms.com) where I solicit suggestions of great stuff. What am I looking for in a great true film? • It must be factual. • It must surprise me, but not preach to me. -

All God's Critters Got a Place in the Choir

All God’s Critters Got a Place in the Choir - Bill Staines - 1979 ===========CHORUS [C] All God's critters got a place in the choir, [G7] Some sing low, [C] some sing higher [F] Some sing out loud on the [C] telephone wires And [G7] some just clap their [C] hands, or paws, or anything they got now ================= [C] Listen to the bass, it's the one on the bottom, Where the [G7] bullfrog croaks and the [C] hippopotamus [F] Moans and groans with a [C] big t'do, And the [G7] old cow just goes [C] moo CHORUS The [C] dogs and the cats they take up the middle While the [G7] honeybee hums and the [C] cricket fiddles The [F] donkey brays and the [C] pony neighs, And the [G7] old coyote [C] howls CHORUS [C] Listen to the top where the little birds sing On the [G7] me-lo-dies with the [C] high notes ringing The [F] hoot owl hollers over [C] everything And the [G7] jaybird disa-[C]-grees [C] Singin' in the night time, singing in the day The [G7] little duck quacks, then he's [C] on his way The [F] 'possum ain't got [C] much to say And the [G7] porcupine talks to [C] himself CHORUS [C] It's a simple song of living sung everywhere By the [G7] ox and the fox and the [C] grizzly gear The [F] grumpy alligator the the [C] hawk above The [G7] sly raccoon and the [C] turtle dove CHORUS ukuleleclare.com BANANAPHONE - by Raffi (1994) D A D A Ring ring ring ring ring ring ring banana phone D A B7 Ring ring ring ring ring ring ring banana phone Em D I've got this feeling, it’s so appealing E7 A7 For us to get together and sing. -

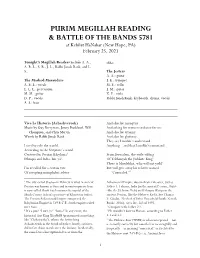

Megillat Ester for KHN 2021 5781 Packet

PURIM MEGILLAH READING & BATTLE OF THE BANDS 5781 at Kehilat HaNahar (New Hope, PA) February 25, 2021 Tonight’s Megillah Readers include A. A., -vs.- A. B. L., S. B., J. L., Rabbi Jonah Rank, and L. S.. The Jesters A. A.: guitar The Masked Marauders J. E.: trumpet A. B. L.: vocals M. E.: cello E. L. L.: percussion J. M.: guitar M. M.: guitar Z. P.: viola D. P.: vocals Rabbi Jonah Rank: keyboards, drums, vocals A. S.: bass Viva La Historia (Achashverosh) And also for misogyny Music by Guy Berryman, Jonny Buckland, Will And asking for women to dance for me Champion, and Chris Martin And also for tyranny Words by Rabbi Jonah Rank. And also for gluttony. They say I couldn’t understand I used to rule the world Anything—and that I couldn’t command. According to the Scripture’s word. Centered in Persian Babylonia1— From Jerusalem, the exile-sibling Ethiopia and India, Ion-ya2. Of Yekhonyah the Judahite King3— There is Mordekhai, who will not yield4 I’m recalled for a certain vice But will give away his relative named Of accepting xenophobic advice “Concealed.” 5 1 The city called Shushan in Hebrew is what in ancient Achaemenid Empire does indicate rule over, just as Persian was known as Susa and in contemporary Iran Esther 1:1 claims, India (in the ancient Persian, Hiduš- is now called Shush (and remains the capital of the -like the Hebrew Hodu) and Ethiopia (Kušiya in the Shush County in Iran’s province of Khuzestan today). ancient Persian, like the Hebrew Kush).