Die Lustigen Weiber Von Windsor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

24 August 2021

24 August 2021 12:01 AM Bruno Bjelinski (1909-1992) Concerto da primavera (1978) Tonko Ninic (violin), Zagreb Soloists HRHRTR 12:11 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Piano Sonata in C major K.545 Young-Lan Han (piano) KRKBS 12:21 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 3 Songs for chorus, Op 42 Danish National Radio Choir, Stefan Parkman (conductor) DKDR 12:32 AM Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824) Serenade for 2 violins in A major, Op 23 no 1 Angel Stankov (violin), Yossif Radionov (violin) BGBNR 12:41 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809),Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757-1831), Harold Perry (arranger) Divertimento 'Feldpartita' in B flat major, Hob.2.46 Academic Wind Quintet BGBNR 12:50 AM Joaquin Nin (1879-1949) Seguida Espanola Henry-David Varema (cello), Heiki Matlik (guitar) EEER 12:59 AM Toivo Kuula (1883-1918) 3 Satukuvaa (Fairy-tale pictures) for piano (Op.19) Juhani Lagerspetz (piano) FIYLE 01:15 AM Edmund Rubbra (1901-1986) Trio in one movement, Op 68 Hertz Trio CACBC 01:35 AM Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) Peer Gynt - Suite No 1 Op 46 Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Ole Kristian Ruud (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Metamorphosen Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, Giordano Bellincampi (conductor) NZRNZ 02:28 AM Max Bruch (1838-1920) Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26 James Ehnes (violin), Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, Giordano Bellincampi (conductor) NZRNZ 02:52 AM Eugene Ysaye (1858-1931) Sonata for Solo Violin in D minor, op. 27/3 James Ehnes (violin) NZRNZ 02:59 AM Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Symphony No. -

Fact Sheet 2009

Wynton Marsalis FACT SHEET 2009 Wynton Marsalis, is the Artistic Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center since its inception in 1987, in addition to performing as Music Director of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra since it began in 1988, has: Early Life . Born on October 18, 1961, in New Orleans, Louisiana, the second of six sons to Ellis and Dolores Marsalis . At age 8, performed traditional New Orleans music in the Fairview Baptist Church band led by legendary banjoist Danny Barker . At age 12, began studying the trumpet seriously and gained experience as a young musician in local marching, jazz and funk bands and classical youth orchestras . At age 14, was invited to perform the Haydn Trumpet Concerto with the New Orleans Philharmonic . At age 17 became the youngest musician ever to be admitted to Tanglewood’s Berkshire Music Center and was awarded the school’s prestigious Harvey Shapiro Award for outstanding brass student . 1979 Entered The Juilliard School in New York City to study classical trumpet . 1979 Sat in with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers to pursue his true love, jazz music. 1980 Joined the band led by acclaimed master drummer Art Blakey . In the years to follow, performed with Sarah Vaughan, Dizzy Gillespie, Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, Sweets Edison, Clark Terry, Sonny Rollins and countless other jazz legends Acclaimed Musician, Composer, Bandleader . 1982 Recording debut as a leader . 1983 Became the first and only artist to win both classical and jazz GRAMMY® Awards in one year . 1984 Won classical and jazz GRAMMY® Awards for a second year . -

Young Leaders’ Responses to a World in Transition

Time for Fresh Air: Young Leaders’ Responses to a World in Transition PACIFIC FORUM CSIS YOUNG LEADERS Issues & Insights Vol. 13 – No. 15 Geneva, Switzerland April 2013 Edited By Billy Tea Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, the Pacific Forum CSIS (www.pacforum.org) operates as the autonomous Asia-Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic, business, and oceans policy issues through analysis and dialogue undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate arenas. Founded in 1975, it collaborates with a broad network of research institutes from around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating project findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and members of the public throughout the region. The Young Leaders Program The Young Leaders Program invites young professionals and scholars to join Pacific Forum policy dialogues and conferences. The program fosters education in the practical aspects of policy-making, generates an exchange of views between young and seasoned professionals, builds adaptive leadership capacity, promotes interaction among younger professionals from different cultures, and enriches dialogues with generational perspectives for all attendees. Young Leaders must have a strong background in the area covered by the conference they are attending and an endorsement from respected experts in their field. Supplemental programs in conference host cities and mentoring sessions with senior officials and specialists add to the Young Leader experience. The Young Leaders Program is possible with generous funding support by governments and philanthropic foundations, together with a growing number of universities, institutes, and organizations also helping to sponsor individual participants. -

Juilliard415 Kristian Bezuidenhout, Harpsichord and Director

Juilliard415 Kristian Bezuidenhout, Harpsichord and Director The Juilliard School presents Juilliard415 Kristian Bezuidenhout, Harpsichord and Director Recorded on April 10, 2021 Peter Jay Sharp Theater HENRY PURCELL Music of the Theater (1659-95) Overture to Dioclesian Hornpipe from King Arthur Rondeau Minuet from The Gordion Knot Untied First Act Tune from The Virtuous Wife Second Music from The Virtuous Wife Rondeau from The Indian Queen Chacony in G Minor J.S. BACH Contrapunctus XIV from The Art of Fugue, arr. for flute, oboe, (1685-1750) and four-part strings Harpsichord Concerto in D Minor, BWV 1052 Allegro Adagio Allegro GEORG PHILIPP Sonata à 5 for two violins, two violas, and basso continuo in TELEMANN G Minor, TWV 44:33 (1681-1767) Grave Allegro Adagio Vivace 1 Welcome to the 2020-21 Historical Performance season! The Historical Performance movement began as a revolution: a reimagining of musical conventions, a rediscovery of instruments, techniques, and artworks that inspire and teach us, and a celebration of diversity in repertoire. It is also a conversation with the past, a past whose legacy of racism and colonialism has silenced and excluded too many voices from being heard. We do not seek simply to recreate what might have been but to imagine what should be. We embrace Juilliard's values of equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging through voices heard anew and historical works presented with empathetic perspectives, and we reject discrimination, exclusion, and marginalization. We recognize that we study and work on the traditional homeland of those who preceded us (see Juilliard's land acknowledgement statement, below). -

German Arias Concert Program

Graduate Vocal Arts Program Bard College Conservatory of Music OPERA WORKSHOP Stephanie Blythe and Howard Watkins, instructors “Thank you, do you have anything in German?” Friday, March 5 at 8pm Wo bin ich? Engelbert Humperdinck (1854 - 1921) from Hänsel und Gretel Diana Schwam, soprano Ryan McCullough, piano Nimmermehr wird mein Herze sich grämen Friedrich von Flotow (1812 - 1883) from Martha Joanne Evans, mezzo-soprano Elias Dagher, piano Glück, das mir verblieb Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 - 1957) from Die tote Stadt Jardena Gertler-Jaffe, soprano Diana Borshcheva, piano Einst träumte meiner sel’gen Base Carl Maria von Weber (1786 - 1826) from Der Freischütz Kirby Burgess, soprano Gwyyon Sin, piano Witch’s Aria Humperdinck from Hänsel und Gretel Maximillian Jansen, tenor Diana Borshcheva, piano Da Anagilda sich geehret… Ich bete sie an Reinhard Kaiser (1674 - 1739) from Die Macht der Tugend Chuanyuan Liu, countertenor Ryan McCullough, piano Arabien, mein Heimatland Weber from Oberon Micah Gleason, mezzo-soprano Gwyyon Sin, piano Da schlägt die Abschiedsstunde Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791) from Der Schauspieldirektor Meg Jones, soprano Sung-Soo Cho, piano Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen Korngold from Die tote Stadt Louis Tiemann, baritone Diana Borshcheva, piano Wie du warst Richard Strauss (1864 - 1949) from Der Rosenkavalier Melanie Dubil, mezzo-soprano Elias Dagher, piano Presentation of the Rose Strauss from Der Rosenkavalier Samantha Martin, soprano Elias Dagher, piano Arie des Trommlers Viktor Ullman (1898 - 1944) from Der Kaiser von Atlantis Sarah Rauch, mezzo-soprano Gwyyon Sin, piano Weiche, Wotan, weiche! Richard Wagner (1813 - 1883) from Das Rheingold Pauline Tan, mezzo-soprano Sung-Soo Cho, piano Nun eilt herbei! Otto Nicolai (1810 - 1849) from Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor Alexis Seminario, soprano Elias Dagher, piano SYNOPSES: Wo bin ich? Hänsel und Gretel Engelbert Humperdinck, Adelheid Wette, 1893 Gretel has just awakened from a deep sleep in the forest. -

2017-18 Season Announcement News Release

N E W S R E L E A S E FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: February 23, 2017 Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra Announce 2017-2018 Season Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s Sixth Season Spans a Vast Range of Sounds Commissions • Oratorio • Chamber Music • Opera A Crowd-Sourced Celebration of Philadelphia • Broadway and a Wide Swath of Orchestral Repertoire Philadelphia Voices, a new work by Tod Machover Tosca Winter Festival focuses on British Isles Hilary Hahn is Artist-in-Residence American Sounds Leonard Bernstein Centenary Including Full Score Performances of West Side Story in Concert Premieres for Orchestra Principals (Philadelphia , February 23, 2017)—Philadelphia Orchestra Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and President and CEO Allison Vulgamore today released The Philadelphia Orchestra’s 2017-18 season. Nézet-Séguin begins his sixth season in Philadelphia with a commitment to lead the world-renowned ensemble through at least 2025-26, continuing a relationship between music director and musicians that has garnered praise around the globe. “This is possibly the most varied season The Philadelphia Orchestra and I have undertaken together,” said Music – more – Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra: 2017-18 Season 2 Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin. “It’s thrilling to be able to make music in every way possible, from playing piano with our wonderful principal strings in chamber music, to conducting new works, including commissions, to an oratorio I adore, to a semi-staged production of Tosca. We have some audience favorites, of course, and naturally we are celebrating the centenary of that amazing musical figure Leonard Bernstein. We hope everyone will join us!” “We truly are celebrating Yannick in every musical way this season, and we’re also celebrating our wonderful city of Philadelphia,” added Philadelphia Orchestra President and CEO Allison Vulgamore. -

Michael William Balfe Maid of Artois

2A that still attract audiences. There is a touch of lightness in Balfe's work that still endears the Maid of Artois to the attentive listener and which makes it an important contribution to the musical history of this land. John Stewart Allitt Michael William Balfe - nicht nur The Bohemian Girl Eine Neuaufnahme der Maid of Artois bei Campion Cameo Records Der Ire Michael Balfe ("Bolf'sagen unsere britischen Vettern) ist auf dem Kontinent (von dem die Briten immer noch sprechen, wenn sie Europa und nicht sich selber meinen) nur durch sein Bohemian Girl bekannt, das nach dem Krieg Thomas Beecham und nach ihm (sehr bodenlastig und und gar nicht interessant) Richard Bonynge auf CD bei Decca zu Ehren gebracht haben. Das muB gut besetzt sein und hat seine Liingen, vor allem wegen des (bei Decca leider eben nicht vorhandenen) Dialogs. Balfe selber (1808 - 70) war ein interessanter Mann, ein schiiner sogar, der seine Zeit in Italien auch zu (Damen)Bekanntschaften nutzte und der griindlich in der Tradition des Belcanto zu Hause war. Er wuchs als Violinwunderkind in Dublin auf, kam mit 14 nach London und begann seine Karriere als Geiger in Drury Lane, wo er schnell zum Orchesterleiter aufstieg. Ein Miizen in Gestalt von Graf Mazzara brachte ihn nach Paris und dann Italien, wo seine Ausbildung in Mailand stattfand, was sich in einem ercten Ballett ("La P6rouse") fiir die Scala niederschlug. In Paris sang er Rossini mit seiner schcinen Baritonstimme das'Largo al factotum'vor, was diesen beeindruckte und Balfe zu einer Gesangsausbildung zuraten lieB. Dieser trat danach als Rossinis Figaro, auch als Conte in Bellinis Sonnambula in Palermo auf. -

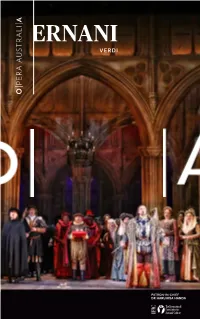

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

A Unique and Extremely Important Collection of Autograph Letters and Manuscripts of the World's Greatest Composers

z 42 P319u A A I ! 1 i 2 I 3 ! 9 I 5 I 1 i 5 I Collection of Autograph Letters and Manuscripts of the World's Greatest Composers THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES A UNIQUE AND EXTREMELY «!) r IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF AUTOGRAPH LETTERS AND MANUSCRIPTS OF THE WORLD'S GREATEST COMPOSERS 9 J. 'PEARSON & CO. 5, PALLTV1ALL PLACE, LONDON, S.W. Telegraphic and Cable Address: "Parabola, London" ALL THE IT£MS IN THIS" CATALOGUE ARE ENTIRELY FREE OF DUTY Loo<4oC> ^^rsoOj £\* tt^b«* takers s ^ A UNIQUE AND EXTREMELY IMPORTANT COLLECTION OF AUTOGRAPH LETTERS AND MANUSCRIPTS OF THE WORLD'S GREATEST COMPOSERS ON SALE BY J. PEARSON fif CO. 5, PALL MALL PLACE, LONDON, S.W. Telegraphic and Cable Address: " Parabola, London" Wf ALL THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE ARE ENTIRELY FREE OF DUTY FOREWORD HIS unique and extremely remarkable collection of autograph letters and original manuscripts of the world's greatest composers comprises no less than seventy-five examples. These letters and manuscripts represent the finest pro- curable examples of such supremely important masters as Handel (a splendid manuscript); Mozart (of whom there are two very early letters written when he was only thirteen years old, being addressed to his mother and sister); Bach; Arne; Wagner (a splendid letter of great length); Beethoven ; Gluck (the finest known letter); Haydn; Mendelssohn; Chopin (very important); Brahms; Liszt; Rossini; Meyer- beer; Cherubini; Donizetti; Schubert (a superb letter); Schumann; Spohr; Spontini; Elgar; Gounod, etc. This noble collection is principally based upon the famous Meyer Cohn cabinet. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

The Perfect Fool (1923)

The Perfect Fool (1923) Opera and Dramatic Oratorio on Lyrita An OPERA in ONE ACT For details visit https://www.wyastone.co.uk/all-labels/lyrita.html Libretto by the composer William Alwyn. Miss Julie SRCD 2218 Cast in order of appearance Granville Bantock. Omar Khayyám REAM 2128 The Wizard Richard Golding (bass) Lennox Berkeley. Nelson The Mother Pamela Bowden (contralto) SRCD 2392 Her son, The Fool speaking part Walter Plinge Geoffrey Bush. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime REAM 1131 Three girls: Alison Hargan (soprano) Gordon Crosse. Purgatory SRCD 313 Barbara Platt (soprano) Lesley Rooke (soprano) Eugene Goossens. The Apocalypse SRCD 371 The Princess Margaret Neville (soprano) Michael Hurd. The Aspern Papers & The Night of the Wedding The Troubadour John Mitchinson (tenor) The Traveller David Read (bass) SRCD 2350 A Peasant speaking part Ronald Harvi Walter Leigh. Jolly Roger or The Admiral’s Daughter REAM 2116 Narrator George Hagan Elizabeth Maconchy. Héloïse and Abelard REAM 1138 BBC Northern Singers (chorus-master, Stephen Wilkinson) Thea Musgrave. Mary, Queen of Scots SRCD 2369 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Leader, Reginald Stead) Conducted by Charles Groves Phyllis Tate. The Lodger REAM 2119 Produced by Lionel Salter Michael Tippett. The Midsummer Marriage SRCD 2217 A BBC studio recording, broadcast on 7 May 1967 Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir John in Love REAM 2122 Cover image : English: Salamander- Bestiary, Royal MS 1200-1210 REAM 1143 2 REAM 1143 11 drowned in a surge of trombones. (Only an ex-addict of Wagner's operas could have 1 The WIZARD is performing a magic rite 0.21 written quite such a devastating parody as this.) The orchestration is brilliant throughout, 2 WIZARD ‘Spirit of the Earth’ 4.08 and in this performance Charles Groves manages to convey my father's sense of humour Dance of the Spirits of the Earth with complete understanding and infectious enjoyment.” 3 WIZARD. -

Sir John in Love

REAM.2122 MONO ADD RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Sir John in Love (1924-28) An Opera in Four Acts Libretto by the composer, based on Shakespeare’s (in order of appearance) Shallow, a country Justice Heddle Nash Sir Hugh Evans, a Welsh Parson Parry Jones Slender, a foolish young gentleman, Shallow’s cousin Gerald Davies Peter Simple, his servant Andrew Gold, Page, a citizen of Windsor Denis Dowling, Sir John Falstaff Roderick Jones Bardolph John Kentish Nym Sharpers attending on Falstaff Denis Catlin Pistol } Forbes Robinson Anne Page, Page’s daughter April Cantelo Mrs Page, Page’s wife Laelia Finneberg Mrs Ford, Ford’s wife Marion Lowe Sir John in Love Fenton, a young gentleman of the Court at Windsor James Johnston Dr. Caius, a French physician Francis Loring Rugby, his servant Ronald Lewis Mrs Quickly, his housekeeper Pamela Bowden The Host of the ‘Garter Inn’ Owen Brannigan Ford, a citizen of Windsor John Cameron The BBC wordmark and the BBC logo are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996 c © Of all the musical forms essayed by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), his operas have received the least recognition or respect. His propensity to write without commissions and to encourage amateur or student groups to premiere his stage pieces 3 EVANS As we sat down in Papylon 4’36” has perhaps played a part in this neglect. Yet he was incontestably a man of the theatre. 4 HOST Peace, I say! 3’04” He produced an extensive, quasi-operatic score of incidental music for Aristophanes’ , for the Cambridge Greek Play production in 1909.