Young Leaders’ Responses to a World in Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

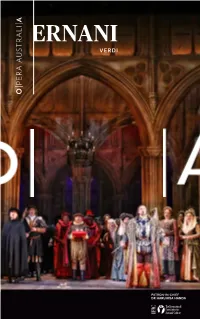

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

2018 World Indoor Championships Statistics - Women’S HJ - by K Ken Nakamura Summary Page

2018 World Indoor Championships Statistics - Women’s HJ - by K Ken Nakamura Summary Page: All time Performance List at the World Indoor Championships Performance Performer Height Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 2.05 Stefka Kostadinova BUL 1 Indianapolis 19 87 2 2 2.04 Yelena Slesarenko RUS 1 Budapest 2004 3 3 2.03 Blanka Vlasic CRO 1 Valencia 2008 4 4 2.02 Susanne Beyer GDR 2 Indianapolis 1987 4 2.02 Stefka Kostadinova 1 Budapest 1989 4 2.02 Stefka Kostadinova 1 Toronto 1993 4 4 2.02 Heike Henkel GER 2 Toronto 1993 4 2.02 Stefka Kostadinova 1 Paris 1997 4 2.02 Yelena Slesarenko 1 Moskva 2006 Lowest winning Height: 1.96m by Vashti Cunningham (USA) in 2016 is the lowest winning Height in history. 1.98m by Chaunte Lowe (USA) in 2012 is the second lowest winning height in the history of the World Indoor; 1.99m by Khristina Kalcheva (BUL) in 1999 is the third lowest winning height; 1.97m by Stefka Kostadinova in 1985 World Indoor Games is even lower. Margin of Victory Difference Height Name Nat Venue Year Max 4cm 2.04m Yelena Slesarenko RUS Budapest 2004 Min 0cm 2.02m Stefka Kostadinova BUL Toronto 1993 2.00m Kajsa Bergqvist UKR Lisboa 2001 1.96m Vasti Cunningham USA Portland 2016 Best Marks for Places in the World Indoor Championships Pos Height Name Nat Venue Year 1 2.05 Stefka Kostadinova BUL Indianapolis 1987 2 2.02 Susanne Beyer GDR Indianapolis 1987 Heike Henkel GER Toronto 1993 2.01 Yelena Slesarenko RUS Valencia 2008 3 2.01 Vita Palamar UKR Valencia 2008 4 1.99 Ruth Beitia ESP Valencia 2008 Multiple Gold Medalists: Blanka Vlasic (CRO): -

World Sports Values Summit Report 2015

World Sports Values Summit for Peace and Development Meeting Report Cape Town, South Africa 2-3 November, 2015 “Cape Town – a beacon of hope and courage to the world.” Foreword 3 The World Sports Values Summit 2015 was held in Cape Town following successful previous summits in London, Tokyo and New York. Sport plays a crucial role in Africa’s development and has at various times served as an instrument for building unity and promoting reconciliation. That is a key reason why the fourth annual Summit was held in Cape Town. The city and South Africa are beacons of hope and courage to the world. Nelson Mandela understood the power of sport to bring people together. Football matches on Robben Island united members of the African National Congress while they were imprisoned. He recognized its power to tackle and reframe racial challenges as seen in his courageous gestures of unity amidst the 1995 Rugby World Cup, hosted and won by a newly united South Africa. He also understood the great symbolic power of sport; one of his last public appearances was at the final of the South Africa 2010 World Cup. The annual Sports Values Summits each focus on the extraordinary role that sport can play in human life. Sport brings disparate peoples together and helps to advance cooperation, development, and even peace. The athletes and leaders who gathered in Cape Town brought direct experience of what can be achieved. With each Summit we seek to learn from promising practices and to determine what we might achieve together in advancing the valuable role that sport can have in modern society. -

Pacific Forum Annual Report 2017

Table of Contents Vision and Mission Statement ………………….……………….. ii Message from the President …………………………………….. 1 2016 Board of Governors ………………………………………… 2 Financials ….……………………………………………………… 5 Endowments …………………………………………………….. 6 Regional Engagement Programs………………………………… 7 Strategic Stability Dialogues ……….……………………… 9 Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific …..……………… 12 Developing the Next Generation………………………………… 15 Engaging with the Hawaii Community ………………..………… 31 Senior Staff Extracurricular Activities…………………………… 40 Publications ……………………………………………..……….. 42 2016 Calendar of Events…………………………………………..44 Appendices Appendix A: Young Leader Publications ………..………………A-1 i . Our Vision The Pacific Forum CSIS envisions an Asia-Pacific region where all states contribute to peace and stability and all people enjoy security, prosperity, and human dignity while governed by the rule of law. Our Mission To enhance mutual understanding and trust, promote sustainable cooperative solutions to common challenges, mitigate conflicts, and contribute to peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific, the Pacific Forum CSIS conducts policy-relevant research and promotes dialogue in the Asia-Pacific region through a network of bilateral and multilateral relationships on a comprehensive set of economic, security, and foreign policy issues. The Pacific Forum's analysis and policy recommendations help create positive change within and among the nations of the Asia-Pacific and beyond. ii MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Aloha! 2016 was a busy and most productive year for the Pacific Forum CSIS as we continue to pursue our founder Joe Vasey’s quest to “find a better way” to handle international disputes and build trust and confidence in our Asia-Pacific neighborhood. We did this by convening almost 90 conferences, dialogues, roundtables, seminars, and workshops throughout the world (19 different cities in eight different countries). -

2017 IFAC Handa Australian Singing Competition Finals Concert

DAMIAN ARNOLD tenor 25* NSW DANIEL CARISON baritone 24* VIC PAULL-ANTHONY KEIGHTLEY bass baritone 25* WA FILIPE MANU tenor 24* NZ SHIKARA 2017 RINGDAHL FINALS mezzo soprano 25* QLD CONCERT SATURDAY 15 JULY 7:00PM *Age as at 23 June 2017 CONCERT HALL, THE CONCOURSE CHATSWOOD COMPERE Margaret Throsby AM ART FORM. TRADITION. FUTURE. The IFAC Handa Australian Singing Competition is Australasia’s premier competition of its kind. Since 1982 the competition has provided cash prizes, awards and career development opportunities for CONDUCTOR young opera & classical singers and is the home Dr. Nicholas Milton AM of the Marianne Mathy Scholarship (‘The Mathy’). AUSSING.ORG GUEST ARTIST Sitiveni Talei Winner 2008 Marianne Mathy Scholarship THE IFAC HANDA AUSTRALIAN SINGING COMPETITION IS ADMINISTERED BY MUSIC & OPERA SINGERS TRUST LTD (MOST®). TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS AND OTHER INITIATIVES, CONTACT US ON – MOSTLYOPERA.ORG OR CALL T 02 9231 4293 PATRON OPERA AUSTRALIA ORCHESTRA Dr. Haruhisa Handa Overture ACADEMIC FESTIVAL / Brahms Chairman, International Foundation DAMIAN ARNOLD of Arts and Culture (IFAC) La fleur que tu m’avais jetéeCARMEN / Bizet DANIEL CARISON Sois Immobile GUILLAME TELL / Rossini PROGRAMME PAULL-ANTHONY KEIGHTLEY APPROXIMATELY 3 HOURS, Vi ravviso, o luoghi ameni LA SONNAMBULA / Bellini WITH A 20-MINUTE INTERVAL FILIPE MANU Pastorello d’un povero armento RODELINA / Handel ADJUDICATORS Catrin Johnsson SHIKARA RINGDAHL (National Adjudicator) The Swimmer SEA PICTURES / Elgar Tahu Matheson DAMIAN ARNOLD Nöemi Nadelmann Il mio tesoro DON GIOVANNI / Mozart Olafur Sigurdarson DANIEL CARISON Raff Wilson Heiterkeit und Fröhlichkeit DER WILDSCHÜTZ ODER DIE STIMME DER NATUR / Lortzing Narelle Yeo PAULL-ANTHONY KEIGHTLEY Fear no more the heat o’ the sun LET US GARLANDS BRING / Finzi The Finals Concert will be broadcast on ABC Classic FM on Sunday 16th July FILIPE MANU Audio Recording: ABC Classic FM Ah mes amis.. -

Ontario Female Outdoor Records

ONTARIO OUTDOOR RECORDS - WOMEN As on July 22, 2021 p = pending ratification (number codes explained below) h = hand timing Explanation of Number Codes for Pending Records: p Ratifiable at next AO Board meeting p(2) Copy of birth certificate required p(3) Officials' verification form required (heights accurately measured, implements checked?) p(4) Nationality/residence at time of performance needs to be verified p(5) Performance information incomplete p(6) Verification of results required p(7) More information on specifications required p(8) Record application form required For lists of discontinued events and lists of performances unratified for administrative reasons please email Randolph Fajardo <[email protected]> In the relay events, athletes whose names are in bold lettering are required to provide proof of age. For further information on this list please contact Randolph Fajardo <[email protected]> Note: As of January 1, 2010, an athlete must have been a registered member of Athletics Ontario on the date the performance was achieved in order to be eligible for a record. Age Group Performance (Wind) Athlete Name (YOB) Club (Representing) City YYYY MM DD 80m U14 10.05 (+0.3) Chelsea AGYEMONG (00) Flying Angels Academy Toronto 2013 07 27 U13 10.67 (+1.1) Arielle TESSIER (99) York University TC Toronto 2011 07 23 100m All Comers 10.95p (+0.9) Sherone SIMPSON (84) Jamaica Toronto 2015 07 22 Open 10.98 (+0.8) Angela BAILEY (62) Etobicoke Huskies-Striders (Team Canada) Budapest, HUN 1987 07 06 U24 11.13 (+0.9) Khamica BINGHAM (94) Brampton T.F.C. (Team Canada) Toronto 2015 07 22 U20 11.21 (+0.0) Angela BAILEY (62) University of Toronto TC (Team Canada) Ciudad Bolivar, VEN 1981 08 15 U19 11.44 (+0.5) Angela BAILEY (62) University of Toronto TC (Team Canada) Philadelphia, USA 1980 07 17 U18 11.53 (+1.8) Khamica BINGHAM (94) Brampton T.F.C. -

2016 Olympic Games Statistics

2016 Olympic Games Statistics - Women’s HJ by K Ken Nakamura Records to look for in Rio de Janeiro: 1) Can Chaunte Lowe win first gold for US since 1988 when Ritter won? 2) Can Beitia win first WHJ medal for ESP in OG? Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Height Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 2.06 Yelena Slesarenko RUS 1 Athinai 2004 2 2 2.05 Stefka Kostadinova BUL 1 Atlanta 1996 2 2 2.05 Tia Hellebaut BEL 1 Beijing 2008 2 2 2.05 Blanka Vlasic CRO 2 Beijing 2008 2 2 2.05 Anna Chicherova RUS 1 London 2012 Lowest winning height since 1984: 2.01 by Yelena Yelesina (RUS) in 2000 Margin of Victory Difference Height Name Nat Venue Year Max 14cm 1.85 Iolanda Balas ROU Roma 1960 10cm 1.90 Iolanda Balas ROU Tokyo 1964 Min 0cm 2.05 Tia Hellebaut BEL Beijing 2008 2.00 Yelena Yelesina RUS Athinai 2000 1.68 Alice Coachman USA London 1948 1.60 Ibolya Csak HUN Berlin 1936 1.657 Jean Shiley USA Los Angeles 1932 Highest jump in each round Round Height Name Nat Venue Year Final 2.06 Yelena Slesarenko RUS Athinai 2004 Qualifying 1.96 Svetlana Radzivil UZB London 2012 1.95 Styopina, Cloete, Hellebaut Beijing 2004 Highest non-qualifier for the final Height Position Name Nat Venue Year 1.92 Kivimyagi, Rifka, Veneva Beijing 2004 Quintero, Lapina, Vlasic Athinai 2000 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Height Name Nat Venue Year 1 2.06 Yelena Slesarenko RUS Athinai 2004 2 2.05 Blanka Vlasic CRO Beijing 2008 3 2.03 Anna Chicherova RUS Beijing 2008 Svetlana Shkolina RUS London 2012 4 2.01 Yelena Slesarenko RUS Beijing -

Kenneth Morgan Golden 23 November 2020 University of Utah, Department of Mathematics 155 S

Kenneth Morgan Golden 23 November 2020 University of Utah, Department of Mathematics 155 S. 1400 E., RM 233, Salt Lake City, UT 84112−0090 801−581−6176 (office) 801−581−6851 (department) [email protected] www.math.utah.edu/∼golden Education B.A. 1980 Dartmouth College, Mathematics and Physics M.S. 1983 New York University, Courant Institute, Mathematics Ph.D. 1984 New York University, Courant Institute, Mathematics Employment 1984−87 NSF Mathematical Sciences Postdoctoral Fellow, Rutgers University 1987−91 Assistant Professor of Mathematics, Princeton University 1991−96 Associate Professor of Mathematics, University of Utah 1996−17 Professor of Mathematics, University of Utah 2007− Adjunct Professor of Biomedical Engineering, University of Utah 2017− Distinguished Professor of Mathematics, University of Utah Professional Summary • Visiting Positions: Institut des Hautes Etudes´ Scientifiques (IHES),´ Stanford University Math Department, Universit`adi Roma 1 Math Department, Universit`adi Napoli Physics De- partment, Moscow Civil Engineering Institute, Universit´ede Provence Aix-Marseille 1 Math Department, Universidade de Sa~oPaulo Math Department, Instituto Nacional de Matem´atica Pura e Aplicada (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Mathematics and Physics Departments, and Universit´ede Paris Nord Math Department. • Research Interests: Sea ice, mathematics of climate, composite materials, percolation theory, homogenization for partial differential equations, phase transitions and statistical mechanics, -

December 2008 Edition

The U.C. Bulletin December 2008 Edition C O N T E N T S 600 full-tuition 2 scholarships awarded New campus under 3 construction Asia Leadership Center 4 hosts 3-day workshop Lecture series brings world 5 leaders to UC Forum addresses Asia’s 6 economic concerns Inter-faith dialogue pushes Congratulations 8 for faith in action New IBS course explores 2008 UC Graduates! 9 garment Iindustry he University of Cambodia would T like to extend a special congratula- UC to publish fi rst tions to the class of 2008. 140 graduates 10 Cambodian encyclopedia received diplomas in the university’s 4th Commencement Ceremony on October Center of English Studies 16, 2008. Best of luck to you and your grows and develops future endeavors. 11 Also honored in this year’s ceremonies were three recipients Honorary Doctorate Student News degree recipients. The Honorary Doctor- 12 ates recognize those supporters of The University of Cambodia who contribute to the growth and development of our University Supporters university and its community. 16 • Lok Chumteav Bun Rany HunSen of The Kingdom of Cambodia received an The University of Cambodia Honorary Doctorate in Humanities 145 Preah Norodom Blvd. P.O. Box 166 • H.E. Jose de Venecia, Jr. of the Philip- Phnom Penh, The Kingdom of Cambodia pines received an Honorary Doctorate in In- Telephone: (855-23) 993-274, 993-275, ternational Relations 993-276 Fax: (855-23) 993-284 • Dr. Horst Posdorf of Germany received www.uc.edu.kh an Honorary Doctorate in Public Administration. University N E W S Scholarships Awarded to 600 First Years Samdech Hun Sen - Haruhisa Handa National Scholarships 2008 A special thanks to Dr. -

Meeting Report

Page Title World Sports Values World Sports Values Summit for Peace and Development Meeting Report United Nations New York City May 22–24, 2014 United Nations New York, May 22–24, 2014 1 The Power of Youth and Sports for Peace and Development Sport is an extraordinary vehicle for bringing people together and offers precious opportunities to emphasize values too often clouded in our modern society. Sport, in its many forms, has a large potential to promote physical and mental well-being, overcome cultural divides, build community, and advance peace and the common good. Sport highlights what humanity shares and what can be achieved in an inclusive environment. Throughout the world, young people are embracing sport as a tool to help reach personal, community, national and international development objectives as well as address some of the challenges that arise from humanitarian crises in both conflict and post-conflict settings. “Sport is increasingly recognized as an important tool in helping the United Nations achieve its objectives, in particular the Millennium Development Goals. By including sport in development and peace programmes in a more systematic way, the United Nations can make full use of this “Through games and sport children learn about the value of the MDGs. Over cost-efficient tool to help us create a better world.” 280,000 participants throughout Mexico, —Ban Ki-moon, United Nations Secretary-General US, Argentina and Guatemala have gone through our program, resulting in better “At Magic Bus, sport is the catalyst “Sport has a crucial role to citizens and empowered young people” that continues to power 250,000 play in the efforts of the —Dina Buchbinder, Founder & Executive children and youth each week in their United Nations to improve Director of Deportes para Compartir daily struggle against poverty. -

2002 Commonwealth Games Athletics

2002 Commonwealth Games Athletics - Mens 100m # Name Country Result (seconds) Gold Kim Collins St. Kitts & Nevis 9.98 Silver Uchenna Emedolu Nigeria 10.11 Bronze Pierre Browne Canada 10.12 4 Deji Aliu Nigeria 10.15 4 Dwight Thomas Jamaica 10.15 6 Jason John Gardener England 10.22 7 Mark Lewis-Francis England 10.54 8 Dwain Anthony Chambers England 11.19 - Abdul Aziz Zakari Ghana 10.17, 5th SF1 - Nick Macrozonaris Canada 10.29, 6th SF1 - Michael Frater Jamaica 10.30, 7th SF1 - Brian Dzingai Zimbabwe 10.59, 8th SF1 - Asafa Powell Jamaica 10.26, 5th SF2 - Eric Nkansah Appiah Ghana 10.29, 6th SF2 - Anson Henry Canada 10.34, 7th SF2 - Joseph Batangdon Cameroon 10.37, 8th SF2 2002 Commonwealth Games Athletics - Mens 200m # Name Country Result (seconds) Gold Frank "Frankie" Fredericks Namibia 20.06 Silver Marlon Devonish England 20.19 Bronze Darren Andrew Campbell England 20.21 4 Dominic Demeritte Bahamas 20.21 5 Abdul Aziz Zakari Ghana 20.29 6 Morne Nagel South Africa 20.35 7 Joseph Batangdon Cameroon 20.36 8 Christian Sean Malcolm Wales 20.39 - Marvin Regis Trinidad & Tobago 21.06, 5th SF1 - Jermaine Joseph Canada 21.09, 6th SF1 - Douglas "Doug" Turner Wales 21.11, 7th SF1 - Ioannis Markoulidis Cyprus 21.16, 8th SF1 - Stephane Buckland Mauritius 20.61, 5th SF2 - Chris Lambert England 21.02, 6th SF2 - Ricardo Williams Jamaica 21.13, 7th SF2 - Dallas Roberts New Zealand 21.17, 8th SF2 2002 Commonwealth Games Athletics - Mens 400m # Name Country Result (seconds) Gold Michael Blackwood Jamaica 45.07 Silver Shane Niemi Canada 45.09 Bronze Avard Moncur -

Outdoor Ontario Provincial Records

ONTARIO OUTDOOR RECORDS - WOMEN As on November 14, 2019 p = pending ratification (number codes explained below) h = hand timing Explanation of Number Codes for Pending Records: p Ratifiable at next AO Board meeting p(2) Copy of birth certificate required p(3) Officials' verification form required (heights accurately measured, implements checked?) p(4) Nationality/residence at time of performance needs to be verified p(5) Performance information incomplete p(6) Verification of results required p(7) More information on specifications required p(8) Record application form required For lists of discontinued events and lists of performances unratified for administrative reasons please email Randolph Fajardo <[email protected]> In the relay events, athletes whose names are in bold lettering are required to provide proof of age. For further information on this list please contact Randolph Fajardo <[email protected]> Note: As of January 1, 2010, an athlete must have been a registered member of Athletics Ontario on the date the performance was achieved in order to be eligible for a record. Age Group Performance (Wind) Athlete Name (YOB) Club (Representing) City YYYY MM DD 80m U14 10.05 (+0.3) Chelsea AGYEMONG (00) Flying Angels Academy Toronto 2013 07 27 U13 10.67 (+1.1) Arielle TESSIER (99) York University TC Toronto 2011 07 23 100m All Comers 10.95p (+0.9) Sherone SIMPSON (84) Jamaica Toronto 2015 07 22 Open 10.98 (+0.8) Angela BAILEY (62) Etobicoke Huskies-Striders (Team Canada) Budapest, HUN 1987 07 06 U24 11.13 (+0.9) Khamica BINGHAM (94) Brampton T.F.C. (Team Canada) Toronto 2015 07 22 U20 11.21 (+0.0) Angela BAILEY (62) University of Toronto TC (Team Canada) Ciudad Bolivar, VEN 1981 08 15 U19 11.44 (+0.5) Angela BAILEY (62) University of Toronto TC (Team Canada) Philadelphia, USA 1980 07 17 U18 11.53 (+1.8) Khamica BINGHAM (94) Brampton T.F.C.