Negotiating the Master Narrative: Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

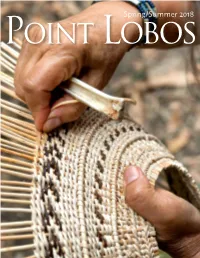

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Natural History Museum Unveils Portrait of Juana María, the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island

Media Contact: Briana Sapp Tivey Director of Marketing and Communications Email: [email protected] Phone: 805-682-4711 ext. 117 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Natural History Museum Unveils Portrait of Juana María, the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island Local Artist Holli Harmon Creates Likeness Based on First-Hand Accounts Santa Barbara, California (February 21, 2018) — The Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History recently unveiled a historically accurate portrait of Juana María, the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island. Fictionalized as “Karana” in Scott O’Dell’s novel Island of the Blue Dolphins, she was a real person who lived by herself on San Nicolas Island. Accidentally left behind in 1835, when the last of the native inhabitants were conveyed to the mainland at the request of the Santa Barbara Mission priests, she resourcefully caught her own food, made her own clothes, and built her own shelter for 18 years. In 1853, Carl Dittman and sea otter hunter Captain George Nidever found the woman alive and well. She willingly returned to the mainland on his ship, living with Nidever’s family in Santa Barbara for only seven weeks before she tragically fell ill and died. The Lone Woman was conditionally baptized with the name Juana María and buried at the Santa Barbara Mission. Harmon’s piece is the first painting to be based on historical records. Most representations of Juana María to date have been based on the romantic image popularized in O’Dell’s book. A research team including archaeologist Steve Schwartz, historian Susan Morris, and Museum Curator of Anthropology John Johnson supplied local artist Holli Harmon with historically accurate descriptions of the Lone Woman. -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes Among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Kristina Marie Gill Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Glassow, Chair Professor Michael A. Jochim Professor Amber M. VanDerwarker Professor Lynn H. Gamble September 2015 The dissertation of Kristina Marie Gill is approved. __________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim __________________________________________ Amber M. VanDerwarker __________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble __________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow, Committee Chair July 2015 Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California Copyright © 2015 By Kristina Marie Gill iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Family, Mike Glassow, and the Chumash People. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have provided guidance, encouragement, and support in my career as an archaeologist, and especially through my undergraduate and graduate studies. For those of whom I am unable to personally thank here, know that I deeply appreciate your support. First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Michael Glassow for his patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement during all aspects of this daunting project. I am also truly grateful to have had the opportunity to know, learn from, and work with my other committee members, Mike Jochim, Amber VanDerwarker, and Lynn Gamble. I cherish my various field experiences with them all on the Channel Islands and especially in southern Germany with Mike Jochim, whose worldly perspective I value deeply. I also thank Terry Jones, who provided me many undergraduate opportunities in California archaeology and encouraged me to attend a field school on San Clemente Island with Mark Raab and Andy Yatsko, an experience that left me captivated with the islands and their history. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

THE VOWEL SYSTEMS of CALIFORNIA HOKAN1 Jeff Good University of California, Berkeley

THE VOWEL SYSTEMS OF CALIFORNIA HOKAN1 Jeff Good University of California, Berkeley Unlike the consonants, the vowels of Hokan are remarkably conservative. —Haas (1963:44) The evidence as I view it points to a 3-vowel proto-system consisting of the apex vowels *i, *a, *u. —Silver (1976:197) I am not willing, however, to concede that this suggests [Proto-Hokan] had just three vowels. The issue is open, though, and I could change my mind. —Kaufman (1988:105) 1. INTRODUCTION. The central question that this paper attempts to address is the motivation for the statements given above. Specifically, assuming there was a Proto-Hokan, what evidence is there for the shape of its vowel system? With the exception of Kaufman’s somewhat equivocal statement above, the general (but basically unsupported) verdict has been that Proto-Hokan had three vowels, *i, *a, and *u. This conclusion dates back to at least Sapir (1917, 1920, 1925) who implies a three-vowel system in his reconstructions of Proto-Hokan forms. However, as far as I am aware, no one has carefully articulated why they think the Proto-Hokan system should have been of one form instead of another (though Kaufman (1988) does discuss some of his reasons).2 Furthermore, while reconstructions of Proto-Hokan forms exist, it has not yet been possible to provide a detailed analysis of the sound changes required to relate reconstructed forms to attested forms. As a result, even though the reconstructions themselves are valuable, they cannot serve as a strong argument for the particular proto vowel system they implicitly or explicitly assume. -

E. Heritage Health Index Participants

The Heritage Health Index Report E1 Appendix E—Heritage Health Index Participants* Alabama Morgan County Alabama Archives Air University Library National Voting Rights Museum Alabama Department of Archives and History Natural History Collections, University of South Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library Alabama Alabama’s Constitution Village North Alabama Railroad Museum Aliceville Museum Inc. Palisades Park American Truck Historical Society Pelham Public Library Archaeological Resource Laboratory, Jacksonville Pond Spring–General Joseph Wheeler House State University Ruffner Mountain Nature Center Archaeology Laboratory, Auburn University Mont- South University Library gomery State Black Archives Research Center and Athens State University Library Museum Autauga-Prattville Public Library Troy State University Library Bay Minette Public Library Birmingham Botanical Society, Inc. Alaska Birmingham Public Library Alaska Division of Archives Bridgeport Public Library Alaska Historical Society Carrollton Public Library Alaska Native Language Center Center for Archaeological Studies, University of Alaska State Council on the Arts South Alabama Alaska State Museums Dauphin Island Sea Lab Estuarium Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository Depot Museum, Inc. Anchorage Museum of History and Art Dismals Canyon Bethel Broadcasting, Inc. Earle A. Rainwater Memorial Library Copper Valley Historical Society Elton B. Stephens Library Elmendorf Air Force Base Museum Fendall Hall Herbarium, U.S. Department of Agriculture For- Freeman Cabin/Blountsville Historical Society est Service, Alaska Region Gaineswood Mansion Herbarium, University of Alaska Fairbanks Hale County Public Library Herbarium, University of Alaska Juneau Herbarium, Troy State University Historical Collections, Alaska State Library Herbarium, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa Hoonah Cultural Center Historical Collections, Lister Hill Library of Katmai National Park and Preserve Health Sciences Kenai Peninsula College Library Huntington Botanical Garden Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park J. -

Native Sustainment: the North Fork Mono Tribe's

Native Sustainment The North Fork Mono Tribe's Stories, History, and Teaching of Its Land and Water Tenure in 1918 and 2009 Jared Dahl Aldern Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from Prescott College in Education with a Concentration in Sustainability Education May 2010 Steven J. Crum, Ph.D. George Lipsitz, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Margaret Field, Ph.D. Theresa Gregor, Ph.D. External Expert Reader External Expert Reader Pramod Parajuli, Ph.D. Committee Chair Native Sustainment ii Copyright © 2010 by Jared Dahl Aldern. All rights reserved. No part of this dissertation may be used, reproduced, stored, recorded, or transmitted in any form or manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder or his agent(s), except in the case of brief quotations embodied in the papers of students, and in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Requests for such permission should be addressed to: Jared Dahl Aldern 2658 East Alluvial Avenue, #103 Clovis, CA 93611 Native Sustainment iii Acknowledgments Gratitude to: The North Fork Mono Tribe, its Chairman, Ron Goode, and members Melvin Carmen (R.I.P.), Lois Conner, Stan Dandy, Richard Lavelle, Ruby Pomona, and Grace Tex for their support, kindnesses, and teachings. My doctoral committee: Steven J. Crum, Margaret Field, Theresa Gregor, George Lipsitz, and Pramod Parajuli for listening, for reading, and for their mentorship. Jagannath Adhikari, Kat Anderson, Steve Archer, Donna Begay, Lisa -

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

An Overview of Ohlone Culture by Robert Cartier

An Overview of Ohlone Culture By Robert Cartier In the 16th century, (prior to the arrival of the Spaniards), over 10,000 Indians lived in the central California coastal areas between Big Sur and the Golden Gate of San Francisco Bay. This group of Indians consisted of approximately forty different tribelets ranging in size from 100–250 members, and was scattered throughout the various ecological regions of the greater Bay Area (Kroeber, 1953). They did not consider themselves to be a part of a larger tribe, as did well- known Native American groups such as the Hopi, Navaho, or Cheyenne, but instead functioned independently of one another. Each group had a separate, distinctive name and its own leader, territory, and customs. Some tribelets were affiliated with neighbors, but only through common boundaries, inter-tribal marriage, trade, and general linguistic affinities. (Margolin, 1978). When the Spaniards and other explorers arrived, they were amazed at the variety and diversity of the tribes and languages that covered such a small area. In an attempt to classify these Indians into a large, encompassing group, they referred to the Bay Area Indians as "Costenos," meaning "coastal people." The name eventually changed to "Coastanoan" (Margolin, 1978). The Native American Indians of this area were referred to by this name for hundreds of years until descendants chose to call themselves Ohlones (origination uncertain). Utilizing hunting and gathering technology, the Ohlone relied on the relatively substantial supply of natural plant and animal life in the local environment. With the exception of the dog, we know of no plants or animals domesticated by the Ohlone. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections.