In the Black Hills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Hills Hydrology Study —By Janet M

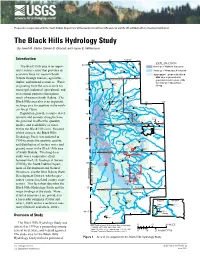

Prepared in cooperation with the South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the West Dakota Water Development District The Black Hills Hydrology Study —By Janet M. Carter, Daniel G. Driscoll, and Joyce E. Williamson o Introduction 104o 45' 103 30' Indian Horse o Belle Fourche EXPLANATION 44 45' Reservoir Cr The Black Hills area is an impor- Owl Newell Outcrop of Madison Limestone BELLE Creek Creek tant resource center that provides an Nisland Outcrop of Minnelusa Formation F BELLE FOURCHE OU economic base for western South RCHE RIVER Approximate extent of the Black Hay Creek R E BUTTE CO Vale Hills area, represented by Dakota through tourism, agriculture, I V ER R MEADE CO REDWAT LAWRENCE CO generalized outer extent of the timber, and mineral resources. Water Cox the outcrop of Inyan Kara Saint Creek Lake Crow Onge Group originating from the area is used for Creek reek municipal, industrial, agricultural, and 30' Gulch Spearfish C Whitewood Bear x Gulch Butte Bottom Creek e recreational purposes throughout ls Bear a Creek F Whitewood Butte Higgins much of western South Dakota. The Cr Creek Squ STURGIS Spearfish a Central Tinton Cr w li Iron CityCr ka ood DEADWOOD l o Black Hills area also is an important Cr w A 103 ad 15' Beaver Cr e D Cr Lead Bear h nnie Cr s A berry recharge area for aquifers in the north- i traw f S r Cr Creek Tilford a hitetail e W p Cheyenne Elk S ern Great Plains. Crossing Little Creek Roubaix ek Creek N Elk re Elk Little C Population growth, resource devel- . -

June PDF Layout

June 2014 The Spearfish Area Chamber of Commerce serves its members as the leading voice of business by providing advocacy, leadership and resources. September 27, 2014 October 28, 2014 Spearfish Park Pavilion Spearfish Convention Center 6:00 PM Annual Fundraiser 9:00 AM - 4:00 PM ERCE Get Your Chance to Win a How is your business connecting online? 2014 Harley Davidson Road King FLHR Learn new tips, tricks and ideas at the Spearfish Area Chamber of Commerce 2014 Only 399 Tickets will be sold at $100 each! Online Marketing Conference: Get Connected Each ticket is admission for two to the General Admission: $99 2014 Flash Back Biker Bash! Spearfish Chamber Member Price: $79 Featuring Admission includes an entry to Whole Roasted Hog Dinner by Cheyenne Crossing WIN an iPad Air! Live Entertainment by the Jeffrey Lloyd Band Enter to Win an iPad Air! Drawing October 28, 2014 2014 Friend of the Chamber Need Not Be Present to Win Tickets one for $5 or five for $20! Thank You to Spearfish Motors for their help! Need Not Be Present to Win June Gone Fishin’ Mixer D.C. Booth Fish Hatchery Gone Fishin’ Mixer A A PUBLICATION OF THE SPEARFISH CHAMBER OF AREA COMM Thursday, June 26th 5:00-7:00 PM 423 Hatchery Circle, Spearfish You have to be visible in the community. You have to get out there and connect with people. It’s not called net-sitting or net-eating. It’s called networking. You have to work at it. www.SpearfishChamber.org Welcome these NEW Chamber Renewing Business Members Business Members ‘Investing in the Business Community’ Black Hills Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, P.C. -

It's Unfair to the People of This Area for Us To

“It’s unfair to the people of this area for us to collect taxes from our customers to help TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority] sell power at a lower price to their customers.” NEIL SIMPSON, President, Black Hills Power and Light Company 60 Expanding Futures on the Great Plains 4 EXPANDING FUTURES ON THE GREAT PLAINS Black Hills Power and Light continued to expand. The company absorbed smaller utilities. It offered power and transmission services to other areas in collaboration with public power agencies and rural electric cooperatives. But tensions with the rural cooperatives were building over territories and customers. As the federal government began to construct dams and hydroelectric facilities on the Missouri River, company officials scrambled to hold onto Black Hills Power and Light’s market and customers. 61 Expanding Futures on the Great Plains Govenor Peter Norbeck’s plan to build a dam dams on the river would revive the state’s proponents of the public power district bill were and hydroelectric facilities on the Missouri River economy. Their efforts to encourage the federal able to convince legislators that new districts after World War I died for lack of sufficient government to build a series of dams gained were needed to secure the power to be generated demand, but the idea lingered in the minds of momentum in 1943 after spring floods caused by Missouri River hydroelectric plants. The public many policymakers in Pierre and Washington, major damage to downstream communities, power district bill passed in 1950. D.C. After drought, depression and war, South especially Omaha, Nebraska. -

Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains Edited by George C

Tri-Services Cultural Resources Research Center USACERL Special Report 97/2 December 1996 U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Construction Engineering Research Laboratory Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort, with contributions by George C. Frison, Dennis L. Toom, Michael L. Gregg, John Williams, Laura L. Scheiber, George W. Gill, James C. Miller, Julie E. Francis, Robert C. Mainfort, David Schwab, L. Adrien Hannus, Peter Winham, David Walter, David Meyer, Paul R. Picha, and David G. Stanley A Volume in the Central and Northern Plains Archeological Overview Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 47 1996 Arkansas Archeological Survey Fayetteville, Arkansas 1996 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Archeological and bioarcheological resources of the Northern Plains/ edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort; with contributions by George C. Frison [et al.] p. cm. — (Arkansas Archeological Survey research series; no. 47 (USACERL special report; 97/2) “A volume in the Central and Northern Plains archeological overview.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56349-078-1 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Great Plains—Antiquities. 2. Indians of North America—Anthropometry—Great Plains. 3. Great Plains—Antiquities. I. Frison, George C. II. Mainfort, Robert C. III. Arkansas Archeological Survey. IV. Series. V. Series: USA-CERL special report: N-97/2. E78.G73A74 1996 96-44361 978’.01—dc21 CIP Abstract The 12,000 years of human occupation in the Northwestern Great Plains states of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota is reviewed here. -

Black Hills Corporation Announces Acquisition of Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power and Approval of Holding Company Application

NEWS RELEASE Black Hills Corporation Announces Acquisition of Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power and Approval of Holding Company Application 1/21/2005 RAPID CITY, S.D., Jan. 21 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Black Hills Corporation (NYSE: BKH) today announced the completion of its acquisition and the assumption of operational responsibility of Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power Company (CLF&P). Black Hills Corporation purchased all the common stock of CLF&P, including the assumption of outstanding debt of approximately $25 million, for approximately $90 million, plus a working capital adjustment to be nalized in the second quarter of 2005. CLF&P was purchased from Xcel Energy Inc. (NYSE: XEL). Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power serves approximately 38,000 electric and 31,000 natural gas customers in Cheyenne and other parts of Laramie County Wyoming. Its electric system peak load is 163 megawatts (MW), and power is supplied to the utility under an all-requirements contract with Public Service Company of Colorado, a subsidiary of Xcel Energy. The all-requirements contract expires in 2007. Annual gas distribution and transportation is approximately 5,000,000 MMBtu (million British thermal units). David R. Emery, President and Chief Executive Ocer of Black Hills Corporation, said, "We welcome this opportunity to serve our new customers in and around Cheyenne and to deliver reliable, value-priced energy. This acquisition increases the scope of our Wyoming-based energy endeavors, which includes power generation, wholesale and retail power delivery, coal mining and oil and natural gas production. We are very pleased with this acquisition and believe it increases our potential to expand our regional presence in the future." REGISTERED HOLDING COMPANY APPLICATION APPROVED The Company also announced that its application for nancing and investment authority in connection with its registration as a holding company under the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 was recently approved by the U.S. -

Black Elk Peak Mobile Scanning Customers & Services Definitive Elevation Bringing the Goods TRUE ELEVATION BLACK ELK PEAK » JERRY PENRY, PS

MAY 2017 AROUND THE BEND Survey Economics Black Elk Peak Mobile Scanning Customers & services Definitive elevation Bringing the goods TRUE ELEVATION BLACK ELK PEAK » JERRY PENRY, PS Displayed with permission • The American Surveyor • May 2017 • Copyright 2017 Cheves Media • www.Amerisurv.com lack Elk Peak, located in the Black Hills region of South Dakota, is the state’s highest natural point. It is frequently referred to as the highest summit in the United States east of the Rocky BMountains. Two other peaks, Guadalupe Peak in Texas and Sierra Blanca Peak in New Mexico, are higher and also east of the Continental Divide, but they are P. Tuttle used a Green’s mercury barometer, one of the considered south of the Rockies. best instruments of the time to determine elevations on The famed Black Elk Peak was known as Harney high peaks. Tuttle coordinated his measurements with Peak as early as 1855 in honor of General William S. simultaneous readings at the Union Pacific Railroad Harney. This designation lasted for more than 160 depot in Cheyenne, Wyo. The difference between the two years, but the peak was renamed Black Elk Peak on barometer readings, when added to the known sea level August 11, 2016, by the U. S. Board of Geographic elevation at Cheyenne, resulted in elevations of 7369.4’ Names to honor medicine man Black Elk of the Oglala and 7368.4’, varying greatly from the 9700’ elevation Lakota (Sioux). The two names are synonymously used previously obtained by Ludlow. in this article as the same peak. The elevation results of the Newton-Jenney The first attempt to accurately measure the elevation of Expedition were not published until 1880 due to the Black Elk Peak was in 1874 during the Custer Expedition. -

Climbing Inyan Kara

SACRED MOUNTAIN Climbing Inyan Kara >> By Jerry Penry, PS Displayed with permission • The American Surveyor • Vol. 10 No. 10 • Copyright 2013 Cheves Media • www.Amerisurv.com rom many miles away, solitary mountains have captured the attention of explorers and surveyors. Undoubtedly, thoughts of climbing to the summit dominated their minds as they drew closer. Likewise, Native Americans were drawn to isolated mountains and even revered them with spiritual practices. Inyan Kara Mountain is located in northeastern Wyoming approximately five miles off the western edge of the Black Hills and 13 miles south of the town of Sundance. The mountain rises to a height of 6370 feet above sea level and, at well over 1300 feet above the surrounding terrain, can be described as a solitary peak. The name, Inyan Kara, is a modern term derived from the Lakota word, “Heeng-ya ka-ga”, which means “rock gatherer”, or “the peak which makes stone”. Inyan means “stone” in the Dakota language. The word Kara is not part of this language, but is thought to have been a corruption of “Ka-ga” which translates, “to make”. The name probably refers to the fact that the mountain has long been a place for native peoples to gather quartzite for knapping into projectile points and Above: Lt. G. K. Warren of the U. S. Topographical Engineers led the first military expedition to Inyan Kara in 1857 resulting in a tense standoff with the Sioux Indians. Library of Congress. Displayed with permission • The American Surveyor • Vol. 10 No. 10 • Copyright 2013 Cheves Media • www.Amerisurv.com The peak of Inyan Kara is hidden by the Above: Chief Red Cloud southeastern portion of the horseshoe- gave a clear message shaped outer rim that surrounds the to Sir George Gore at mountain. -

SOPA) 01/01/2019 to 03/31/2019 Black Hills National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2019 to 03/31/2019 Black Hills National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Black Hills National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R2 - Rocky Mountain Region RNA and BA Mineral - Special area management In Progress: Expected:05/2019 06/2019 Kelly Honors Withdrawal - Minerals and Geology Comment Period Public Notice 605-673-9207 EA - Land ownership management 09/24/2015 [email protected] *UPDATED* Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2019 Description: Proposed withdrawal of research natural areas and botanical areas from mineral entry. Necessary part of RNA designation process. Forest Service recommendation to BLM, who makes the decision. Project not subject to the objection process. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=45590 Location: UNIT - Black Hills National Forest All Units. STATE - South Dakota, Wyoming. COUNTY - Custer, Lawrence, Pennington, Crook. LEGAL - Not Applicable. This proposal addresses four Research Natural Areas and seven Botanical Areas totaling about 17,000 acres at various locations in South Dakota and Wyoming. Rushmore Connector Trail - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:04/2019 10/2019 Kelly Honors Project - Special use management NOI in Federal Register 605-673-9207 EIS 06/07/2016 [email protected] Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 12/2018 Description: The State of South Dakota has applied for a permit to construct, operate and maintain a 14-mile non-motorized trail across the Forest connecting the Mickelson Trail to Mt. -

Southwestern Showy Sedge in the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming

United States Department of Agriculture Conservation Assessment Forest Service Rocky of the Southwestern Mountain Region Black Hills Showy Sedge in the Black National Forest Custer, Hills National Forest, South South Dakota May 2003 Dakota and Wyoming Bruce T. Glisson Conservation Assessment of Southwestern Showy Sedge in the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming Bruce T. Glisson, Ph.D. 315 Matterhorn Drive Park City, UT 84098 email: [email protected] Bruce Glisson is a botanist and ecologist with over 10 years of consulting experience, located in Park City, Utah. He has earned a B.S. in Biology from Towson State University, an M.S. in Public Health from the University of Utah, and a Ph.D. in Botany from Brigham Young University EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Southwestern showy sedge, Carex bella Bailey, is a cespitose graminoid that occurs in the central and southern Rocky Mountain region of the western United States and Mexico, with a disjunct population in the Black Hills that may be a relict from the last Pleistocene glaciation (Cronquist et al., 1994; USDA NRCS, 2001; NatureServe, 2001). Southwestern showy sedge is quite restricted in range and habitat in the Black Hills. There is much that we don’t know about the species, as there has been no thorough surveys, no monitoring, and very few and limited studies on the species in the area. Long term persistence of southwestern showy sedge is enhanced due to the presence of at least several populations within the Black Elk Wilderness and Custer State Park. Populations in Custer State Park may be at greater risk due to recreational use and lack of protective regulations (Marriott 2001c). -

Johnny Sundby, South Dakota Office of Tourism, Adams Museum & House, Mark Nordby, Doug Hyun/HBO

© Crazy Horse Memorial Fnd. Photography Credits: Johnny Sundby, South Dakota Office of Tourism, Adams Museum & House, Mark Nordby, Doug Hyun/HBO. Adams Museum & House, Mark Nordby, South Dakota Office of Tourism, Photography Credits: Johnny Sundby, Long before the modern day gaming halls were built, Deadwood was Deadw known as a lawless town run by ood TV Serie infamous gamblers and gunslingers. s Bars, brothels and gaming halls made up this tiny town in the Black Hills of South Dakota that was home to legendary characters like Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane. Histo ric Reenactors While men like Sheriff Seth Bullock k ll Hicko and Mayor E.B. Farnum tried to tame Wild Bi the town, the outlaw spirit never really died. Today, when you stand on Historic Main Street you’re transported back to a wilder time… when whiskey ruled and gamblers took a chance just walking down the street. Calamity Jane 1 2 Poker With ongoing restoration, Deadwood is being transformed back into the frontier town that once drew legends and legions in search of their fortune. The entire town is a registered National Historic Landmark. But don’t let that fool you–behind all the historic facades is plenty of modern-day fun. Our world-class gaming halls have $100 bet limits and feature luxury accommodations and some of the finest cuisine anywhere. Play slots or try Blackjack your luck at one of our blackjack, Three-card, or Texas Hold’em tables. er ard Pok 3 Three C 4 Red Cloud The Dakota Territory was a fairly uninhabited place until gold was discovered in 1874 by Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s expedition. -

Black Hills National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Rocky Black Hills Mountain Region Black Hills National National Forest Forest Custer South Dakota March 2006 Land and Resource Management Plan 1997 Revision Phase II Amendment LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS ACHP President’s Advisory Council on MMBF Million Board Feet Historic Preservation MMCF Million Cubic Feet A.F.F. Agricultural, Forestry, and Fishing MOU Memorandum of Understanding Services MPB Mountain Pine Beetle AMP Allotment Management Plan NAAQS National Ambient Air Quality AOI Annual Operating Instructions Standards ARC At-risk Communities NEPA National Environmental Policy Act ASQ Allowable Sale Quantity NF National Forest ATV All Terrain Vehicle NFMA National Forest Management Act AUM Animal Unit Month NFP National Fire Plan BA Botanical Areas NFPA National Forest Protection BA Biological Assessment Association BBC Birds of Conservation Concern NFS National Forest System BBS Breeding Bird Survey National Register National Register of Historic Places BCR Bird Conservation Regions NIC Non-Interchangeable Component BE Biological Evaluation NOA Notice of Availability BHNF Black Hills National Forest NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Black Hills Black Hills Ecoregion Administration BLM Bureau of Land Management NOI Notice of Intent BMP Best Management Practices NWCG National Wildland Fire Coordinating BOR Bureau of Recreation Group BTU British Thermal Unit OHV Off Highway Vehicle CEQ Council on Environmental Quality PCPI Per Capita Personal Income CF Cubic Feet PIF Partners -

Geology and Petrology of the Devils Tower, Missouri Buttes, and Barlow Canyon Area, Crook County, Wyoming Don L

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 1980 Geology and petrology of the Devils Tower, Missouri Buttes, and Barlow Canyon area, Crook County, Wyoming Don L. Halvorson University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Halvorson, Don L., "Geology and petrology of the Devils Tower, Missouri Buttes, and Barlow Canyon area, Crook County, Wyoming" (1980). Theses and Dissertations. 119. https://commons.und.edu/theses/119 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEOLOGY AND PETROLOGY OF THE DEVILS TOWER, MISSOURI BUTTES, AND BARLOW CANYON AREA, CROOK c.OUNTY, WYOMING by Don L. Halvorson Bachelor of Science, University of Colorado, 1965 Master of Science Teaching, University of North Dakota, 1971 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Grand Forks, North Dakota May 1980 Th:ls clisserratio.1 submitted by Don L. Halvol'.'son in partial ful fillment of the requirements fo1· the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of North Dakota is hereby approved by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whora the work has been done. This dissertation meets the standards for appearance aud con forms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby approved.