Black Hills Resilient Landscapes Project Final Environmental Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Hills Hydrology Study —By Janet M

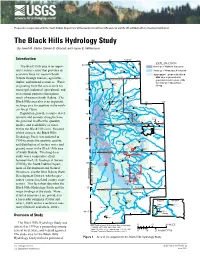

Prepared in cooperation with the South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the West Dakota Water Development District The Black Hills Hydrology Study —By Janet M. Carter, Daniel G. Driscoll, and Joyce E. Williamson o Introduction 104o 45' 103 30' Indian Horse o Belle Fourche EXPLANATION 44 45' Reservoir Cr The Black Hills area is an impor- Owl Newell Outcrop of Madison Limestone BELLE Creek Creek tant resource center that provides an Nisland Outcrop of Minnelusa Formation F BELLE FOURCHE OU economic base for western South RCHE RIVER Approximate extent of the Black Hay Creek R E BUTTE CO Vale Hills area, represented by Dakota through tourism, agriculture, I V ER R MEADE CO REDWAT LAWRENCE CO generalized outer extent of the timber, and mineral resources. Water Cox the outcrop of Inyan Kara Saint Creek Lake Crow Onge Group originating from the area is used for Creek reek municipal, industrial, agricultural, and 30' Gulch Spearfish C Whitewood Bear x Gulch Butte Bottom Creek e recreational purposes throughout ls Bear a Creek F Whitewood Butte Higgins much of western South Dakota. The Cr Creek Squ STURGIS Spearfish a Central Tinton Cr w li Iron CityCr ka ood DEADWOOD l o Black Hills area also is an important Cr w A 103 ad 15' Beaver Cr e D Cr Lead Bear h nnie Cr s A berry recharge area for aquifers in the north- i traw f S r Cr Creek Tilford a hitetail e W p Cheyenne Elk S ern Great Plains. Crossing Little Creek Roubaix ek Creek N Elk re Elk Little C Population growth, resource devel- . -

It's Unfair to the People of This Area for Us To

“It’s unfair to the people of this area for us to collect taxes from our customers to help TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority] sell power at a lower price to their customers.” NEIL SIMPSON, President, Black Hills Power and Light Company 60 Expanding Futures on the Great Plains 4 EXPANDING FUTURES ON THE GREAT PLAINS Black Hills Power and Light continued to expand. The company absorbed smaller utilities. It offered power and transmission services to other areas in collaboration with public power agencies and rural electric cooperatives. But tensions with the rural cooperatives were building over territories and customers. As the federal government began to construct dams and hydroelectric facilities on the Missouri River, company officials scrambled to hold onto Black Hills Power and Light’s market and customers. 61 Expanding Futures on the Great Plains Govenor Peter Norbeck’s plan to build a dam dams on the river would revive the state’s proponents of the public power district bill were and hydroelectric facilities on the Missouri River economy. Their efforts to encourage the federal able to convince legislators that new districts after World War I died for lack of sufficient government to build a series of dams gained were needed to secure the power to be generated demand, but the idea lingered in the minds of momentum in 1943 after spring floods caused by Missouri River hydroelectric plants. The public many policymakers in Pierre and Washington, major damage to downstream communities, power district bill passed in 1950. D.C. After drought, depression and war, South especially Omaha, Nebraska. -

Fisheries Management Plan for Black Hills Streams 2015 – 2019

Fisheries Management Plan for Black Hills Streams 2015 – 2019 South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks Wildlife Division Gene Galinat Greg Simpson Bill Miller Jake Davis Michelle Bucholz John Carreiro Dylan Jones Stan Michals Fisheries Management Plan for Black Hills Streams, 2015-2019 Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 II. Resource Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 4 Black Hills Fish Management Area ...................................................................................... 4 III. Management of Black Hills Fish Management Area Stream Fisheries ...................... 7 Classification of Trout Streams ............................................................................................. 7 Regulations .............................................................................................................................. 7 Stocking .................................................................................................................................... 8 Fish Surveys ............................................................................................................................ 8 Angler Surveys ........................................................................................................................ 9 Habitat and Angler Access ................................................................................................... -

Black Hills Corporation Announces Acquisition of Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power and Approval of Holding Company Application

NEWS RELEASE Black Hills Corporation Announces Acquisition of Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power and Approval of Holding Company Application 1/21/2005 RAPID CITY, S.D., Jan. 21 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Black Hills Corporation (NYSE: BKH) today announced the completion of its acquisition and the assumption of operational responsibility of Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power Company (CLF&P). Black Hills Corporation purchased all the common stock of CLF&P, including the assumption of outstanding debt of approximately $25 million, for approximately $90 million, plus a working capital adjustment to be nalized in the second quarter of 2005. CLF&P was purchased from Xcel Energy Inc. (NYSE: XEL). Cheyenne Light, Fuel & Power serves approximately 38,000 electric and 31,000 natural gas customers in Cheyenne and other parts of Laramie County Wyoming. Its electric system peak load is 163 megawatts (MW), and power is supplied to the utility under an all-requirements contract with Public Service Company of Colorado, a subsidiary of Xcel Energy. The all-requirements contract expires in 2007. Annual gas distribution and transportation is approximately 5,000,000 MMBtu (million British thermal units). David R. Emery, President and Chief Executive Ocer of Black Hills Corporation, said, "We welcome this opportunity to serve our new customers in and around Cheyenne and to deliver reliable, value-priced energy. This acquisition increases the scope of our Wyoming-based energy endeavors, which includes power generation, wholesale and retail power delivery, coal mining and oil and natural gas production. We are very pleased with this acquisition and believe it increases our potential to expand our regional presence in the future." REGISTERED HOLDING COMPANY APPLICATION APPROVED The Company also announced that its application for nancing and investment authority in connection with its registration as a holding company under the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 was recently approved by the U.S. -

South Dakota Line List: 04/03/2020 Beg Mile End Mile Tract Number Feature Use County Post Post ML-SD-HA-00020.000-ROW ROW Harding 285.69 286.08

South Dakota Line List: 04/03/2020 Beg Mile End Mile Tract Number Feature Use County Post Post ML-SD-HA-00020.000-ROW ROW Harding 285.69 286.08 ML-SD-HA-00030.000-ROW ROW Harding 286.08 286.31 ML-SD-HA-00050.000-ROW ROW Harding 286.31 286.39 ML-SD-HA-00040.000-ROW ROW Harding 286.39 286.91 ML-SD-HA-00055.000-ROW ROW Harding 286.91 287.25 ML-SD-HA-00060.000-ROW ROW Harding 287.25 287.32 ML-SD-HA-00080.000-ROW ROW Harding 287.32 288.57 ML-SD-HA-00100.000-ROW ROW Harding 288.57 288.83 ML-SD-HA-00090.000-ROW ROW Harding 288.57 288.68 ML-SD-HA-00130.000-ROW ROW Harding 288.83 289.42 ML-SD-HA-00120.000-ROW ROW Harding 289.42 289.50 ML-SD-HA-00110.000-ROW ROW Harding 289.50 290.01 ML-SD-HA-00160.000-ROW ROW Harding 290.01 290.44 ML-SD-HA-00200.000-ROW ROW Harding 290.44 290.60 ML-SD-HA-00210.000-ROW ROW Harding 290.60 291.18 ML-SD-HA-00230.000-ROW ROW Harding 291.18 292.32 ML-SD-HA-00260.000-ROW ROW Harding 292.32 292.52 ML-SD-HA-00290.000-ROW ROW Harding 292.52 292.88 ML-SD-HA-00295.000-ROW ROW Harding 292.88 293.45 ML-SD-HA-00320.000-ROW ROW Harding 293.45 294.50 ML-SD-HA-00330.000-ROW ROW Harding 294.00 294.33 ML-SD-HA-00350.000-ROW ROW Harding 294.50 294.62 ML-SD-HA-00390.000-ROW ROW Harding 294.62 295.08 ML-SD-HA-00410.000-ROW ROW Harding 295.12 295.21 ML-SD-HA-00420.000-ROW ROW Harding 295.21 295.78 ML-SD-HA-00460.000-ROW ROW Harding 295.78 296.39 ML-SD-HA-00470.000-ROW ROW Harding 296.39 296.43 ML-SD-HA-00510.000-ROW ROW Harding 296.43 297.12 ML-SD-HA-00530.000-ROW ROW Harding 297.12 298.26 ML-SD-HA-00570.000-ROW ROW Harding 298.26 298.56 -

Southwestern Showy Sedge in the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming

United States Department of Agriculture Conservation Assessment Forest Service Rocky of the Southwestern Mountain Region Black Hills Showy Sedge in the Black National Forest Custer, Hills National Forest, South South Dakota May 2003 Dakota and Wyoming Bruce T. Glisson Conservation Assessment of Southwestern Showy Sedge in the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming Bruce T. Glisson, Ph.D. 315 Matterhorn Drive Park City, UT 84098 email: [email protected] Bruce Glisson is a botanist and ecologist with over 10 years of consulting experience, located in Park City, Utah. He has earned a B.S. in Biology from Towson State University, an M.S. in Public Health from the University of Utah, and a Ph.D. in Botany from Brigham Young University EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Southwestern showy sedge, Carex bella Bailey, is a cespitose graminoid that occurs in the central and southern Rocky Mountain region of the western United States and Mexico, with a disjunct population in the Black Hills that may be a relict from the last Pleistocene glaciation (Cronquist et al., 1994; USDA NRCS, 2001; NatureServe, 2001). Southwestern showy sedge is quite restricted in range and habitat in the Black Hills. There is much that we don’t know about the species, as there has been no thorough surveys, no monitoring, and very few and limited studies on the species in the area. Long term persistence of southwestern showy sedge is enhanced due to the presence of at least several populations within the Black Elk Wilderness and Custer State Park. Populations in Custer State Park may be at greater risk due to recreational use and lack of protective regulations (Marriott 2001c). -

Region Forest Number Forest Name Wilderness Name Wild

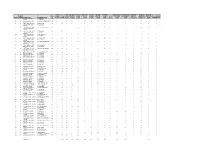

WILD FIRE INVASIVE AIR QUALITY EDUCATION OPP FOR REC SITE OUTFITTER ADEQUATE PLAN INFORMATION IM UPWARD IM NEEDS BASELINE FOREST WILD MANAGED TOTAL PLANS PLANTS VALUES PLANS SOLITUDE INVENTORY GUIDE NO OG STANDARDS MANAGEMENT REP DATA ASSESSMNT WORKFORCE IM VOLUNTEERS REGION NUMBER FOREST NAME WILDERNESS NAME ID TO STD? SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE FLAG SCORE SCORE COMPL FLAG COMPL FLAG SCORE USED EFF FLAG 02 02 BIGHORN NATIONAL CLOUD PEAK 080 Y 76 8 10 10 6 4 8 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST WILDERNESS 02 03 BLACK HILLS NATIONAL BLACK ELK WILDERNESS 172 Y 84 10 10 4 10 10 10 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP FOSSIL RIDGE 416 N 59 6 5 2 6 8 8 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LA GARITA WILDERNESS 032 Y 61 6 3 10 4 6 8 8 N 6 6 Y N 4 Y GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LIZARD HEAD 040 N 47 6 3 2 4 6 4 6 N 6 8 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP MOUNT SNEFFELS 167 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP POWDERHORN 413 Y 62 6 6 2 6 8 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP RAGGEDS WILDERNESS 170 Y 62 0 6 10 6 6 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP UNCOMPAHGRE 037 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP WEST ELK WILDERNESS 039 N 56 0 6 10 6 6 4 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 06 MEDICINE BOW-ROUTT ENCAMPMENT RIVER 327 N 54 10 6 2 6 6 8 6 -

Map of the Hills

From Broadus, - Little Bighorn From Buffalo, SD Belle Fourche Reservoir From Bowman, ND From Faith, SD Z Rocky Point Devils Tower Battlefield and Alzada, MT and Medora, ND State Rec. Area Orman Dam and Dickinson, ND and Lemmon, SD National Monument Belle Fourche River 212 J 85 212 From Devils Tower Tri-State Museum NEWELL and Hulett, Wyo 22 BLACK ? Center of the Nation 212 NISLAND 24 34 Monument 10 Belle Fourche ALADDIN McNenny River 543 Fish Hatchery BELLE FOURCHE Mirror Lake EL3021 VALE HILLS 111 10 20 21 34 BEULAH 17 & BADLANDS 90 19 ? 2 85 Spearfish Rec & ST. ONGE 14 8 Aquatic Center 79 205 10 18 D.C. Booth Historic ofSouth Dakota 10 12 19 Nat’l Fish Hatchery & Northeastern Wyoming ? 14 17 SPEARFISH J 23 3 EL3645 90 Bear Butte 863 WHITEWOOD Bear Butte State Park 34 MAP LEGEND Crow Peak EL3654 Lake From Devils Tower, Wyo Tower, From Devils Termeshere Gallery & Museum Tatanka Story of ©2018 by BH&B 134 14A High Plains Western the Bison Computer generated by BH&B Citadel 30 Bear Butte Creek ? SUNDANCE 130 Spearfish Heritage Center Boulder Canyon 112 EL4744 Rock Peak 85 14 STURGIS Interchange Exit Number Byway Golf Club at EL3421 14 U.S. Hwy. Marker 214 195 Broken Boot 8 6 J Bridal Apple Springs 44 Scenic Veil Falls Gold Mine State Hwy. Marker Mt. Theo DEADWOOD ? Iron Creek Black Hills Roosevelt 14A Canyon 32 Ft. Meade Old Ft. Meade 21 Forest Service Road EL4537 Grand Canyon Lake Mining Museum Canyon Little 133 12 Moskee Hwy. 134 Boulder 18 Crow Peak Museum 4 County Road Adventures at Sturgis Motorcycle 141 Cement Ridge Museum 170 34 ? Visitor Information Lookout Spearfish 19 CENTRAL CITY Days of 76 Museum Canyon Lodge Spearfish ? ? & Hall of Fame Bikers 7 Mileage Between Stars 222 Spearfish Historic LEAD 103 Falls Homestake EL5203 Adams Museum & House 170 Black Hills Scenic SAVOY PLUMA 79 37 Byway Paved Highway 807 Opera House 3 National Dwd Mini-Golf & Arcade 18 Cemetery Multi-Lane Divided Hwy. -

I-29 - Exit 62 to Exit 73 INTERSTATE Corridor Study 29

July 2018 I-29 - Exit 62 to Exit 73 INTERSTATE Corridor Study 29 Project No: HP 5596 19 prepared for: South Dakota Department of Transportation 700 East Broadway Avenue Pierre, SD 57501 I-29 Exit 62 to Exit 73 Corridor Study Lincoln County, SD Project No: HP 5596 19 Prepared for: South Dakota Department of Transportation 700 East Broadway Avenue Pierre, SD 57501 Prepared by: Felsburg Holt and Ullevig 11422 Miracle Hills Drive, Suite 115 Omaha, NE 68154 402-445-4405 In Association with SRF Consulting Group, Inc. Principal-in-Charge / Project Manager: Kyle Anderson, PE, PTOE Deputy Project Manager: Mark Meisinger, PE, PTOE FHU Reference No. 17-089 July 2018 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant(s) from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. The South Dakota Department of Transportation (SDDOT) provides services without regard to race, color, gender, religion, national origin, age or disability, according to the provisions contained in SDCL 20-13, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended, the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 and Executive Order 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, 1994. To request additional information on the SDDOT’s Title VI/Nondiscrimination policy or to file a discrimination complaint, please contact the Department’s Civil Rights Office at 605-773-3540. -

Lakamie Basin, Wyoming

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BULLETIN 364 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE LAKAMIE BASIN, WYOMING A PRELIMINARY REPORT BY N. H. DARTON AND C. E. SIEBENTHAL WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1909 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction............................................................. 7 Geography ............................................................... 8 Configuration........................................................ 8 Drainage ............................................................ 9 Climate ............................................................. 9 Temperature...................................................... 9 Precipitation..................................................... 10 Geology ................................................................. 11 Stratigraphy.......................................................... 11 General relations........................../....................... .11 Carboniferous system............................................. 13 Casper formation......................... .................... 13. General character........................................ 13 Thickness ............................................... 13 Local features............................................ 14 Erosion and weathering of limestone slopes ................ 18 Paleontology and age..................................... 19 Correlation .............................................. 20 Forelle limestone............................................ -

Pgrounds, Meadows, and Watercourses in the Black Hills

The Affected Environment and Consequences 3-3.3.5. Species Of Local Concern – Mammals 3-3.3.5.1. Long-Eared Myotis (Myotis evotis) Affected Environment The long-eared myotis ranges across much of montane western North America, extending from central British Columbia; the southern half of Alberta and the southwestern corner of Saskatchewan; south to Baja California along the Pacific coast; along the western edges of the Dakotas; and most ofWyoming and Colorado to northwestern New Mexico and northeastern Arizona (Schmidt 2003a). The only records of long-eared myotis in the Black Hills come from unpublished reports (Schmidt 2003a). Clark and Stromberg (1987) report long-eared myotis to occur in suitable habitat throughout Wyoming although the majority of the records are from the western half of the state. Luce et al. (1999) reported long-eared myotis in 22 of the 28 surveys in Wyoming but in only one of the two in the Black Hills counties of Wyoming. It is unknown whether the Black Hills supports a self-sustaining population (Schmidt 2003a). This species is associated with coniferous montane habitats and has been reported foraging among trees and over woodland ponds (Schmidt 2003a). Limited data suggest that the long-eared myotis uses ponderosa pine snags as summer and maternity roosts in other regions (Rabe et al. 1998, Vonhof and Barclay 1997). Rabe et al. (1998) summarize some key snag characteristics for the long-eared myotis and four other bat species in Arizona: roost snags were generally in larger dbh, had more loose bark, and were found at higher densities. -

South Dakota Modern Residential Architecture Context Study, 1950-1975

MODERN RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTH DAKOTA, 1950-1975 A THEMATIC CONTEXT STUDY AUGUST 2017 MODERN RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTH DAKOTA, 1950-1975 A THEMATIC CONTEXT STUDY Prepared for South Dakota Department of Education South Dakota State Historical Society State Historic Preservation Office 900 Governors Drive Pierre, South Dakota 57501 History.sd.gov/Preservation Prepared by Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. 151 Walton Avenue Lexington, Kentucky 40508 www.crai-ky.com _________________ S. Alan Higgins, M.S. Principal Investigator This activity has been financed with federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior through the South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. This program receives federal financial assistance from the National Park Service. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, age, sex, or handicap in its federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 210 I Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. CONTENTS 1 | BACKGROUND INFORMATION 01 I. INTRODUCTION 03 A. Purpose and Need 04 B.