SIL Three-Letter Codes for Identifying Languages: Migrating from In-House Standard to Community Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standards for Language Coding: the ISO 639 Family

Standards for language coding: the ISO 639 family Rebecca Guenther Library of Congress Jan. 8, 2010 ISO Standards development !! ISO consists of Technical Committees (TC) with subcommittees (SC) !! ISO language coding standards are maintained by !! TC 37/SC2 (Terminology and other language and content resources ) !! TC 46/SC4 (Information and documentation) LSA Annual Meeting 2 ISO 639 standards !! ISO 639-1: 2-character codes (136 codes) !! ISO 639-2: 3-character codes (450+) !! ISO 639-3: 3-character codes (7700+) !! ISO 639-4: principles !! ISO 639-5: 3-character codes (114) !! ISO 639-6: 4-character codes (??) LSA Annual Meeting 3 ISO 639 Joint Advisory Committee !! Established to advise the RAs for ISO 639-1 and ISO 639-2 !! Rotating chairs: Infoterm (for TC37) and Library of Congress (for TC46) !! Committee consists of 3 members of each TC, representatives of each registration authority and up to 6 observers !! Coordinates development of different parts of ISO 639 LSA Annual Meeting 4 ISO 639 language coding principles !! Language codes are not changed for stability of standard !! If a language code is retired it is not reassigned to something else !! Programming languages are not in scope !! Only deals with languages; codes from other ISO standards may be added as needed for more granularity, e.g. country codes, script codes LSA Annual Meeting 5 ISO 639-1 !! First published 1967 !! Covers major languages of the world !! Alpha-2 codes; only 676 possible combinations !! Developed for use in terminology applications !! Consists of -

Tags for Identifying Languages File:///C:/W3/International/Draft-Langtags/Draft-Phillips-Lan

Tags for Identifying Languages file:///C:/w3/International/draft-langtags/draft-phillips-lan... Network Working Group A. Phillips, Ed. TOC Internet-Draft webMethods, Inc. Expires: October 7, 2004 M. Davis IBM April 8, 2004 Tags for Identifying Languages draft-phillips-langtags-02 Status of this Memo This document is an Internet-Draft and is in full conformance with all provisions of Section 10 of RFC2026. Internet-Drafts are working documents of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), its areas, and its working groups. Note that other groups may also distribute working documents as Internet-Drafts. Internet-Drafts are draft documents valid for a maximum of six months and may be updated, replaced, or obsoleted by other documents at any time. It is inappropriate to use Internet-Drafts as reference material or to cite them other than as "work in progress." The list of current Internet-Drafts can be accessed at http://www.ietf.org/ietf/1id-abstracts.txt. The list of Internet-Draft Shadow Directories can be accessed at http://www.ietf.org/shadow.html. This Internet-Draft will expire on October 7, 2004. Copyright Notice Copyright (C) The Internet Society (2004). All Rights Reserved. Abstract This document describes a language tag for use in cases where it is desired to indicate the language used in an information object, how to register values for use in this language tag, and a construct for matching such language tags, including user defined extensions for private interchange. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. The Language Tag 2.1 Syntax 2.2 Language Tag Sources 2.2.1 Pre-Existing RFC3066 Registrations 1 of 20 08/04/2004 11:03 Tags for Identifying Languages file:///C:/w3/International/draft-langtags/draft-phillips-lan.. -

Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras Twentieth Edition Data

Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras Twentieth edition data Gary F. Simons and Charles D. Fennig, Editors Based on information from the Ethnologue, 20th edition: Simons, Gary F. and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2017. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twentieth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online: http://www.ethnologue.com. For personal use only Permission to distribute or reuse this work (in whole or in part) may be obtained through the Copyright Clearance Center at http://www.copyright.com. SIL International, 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road, Dallas, Texas 75236-5699 USA Web: www.sil.org, Phone: +1 972 708 7404, Email: [email protected] Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras 2 Contents List of Abbreviations 3 How to Use This Digest 4 Country Overview 6 Language Status Profile 7 Statistical Summaries 8 Alphabetical Listing of Languages 11 Language Map 14 Languages by Population 15 Languages by Status 16 Languages by Department 18 Languages by Family 19 Language Code Index 20 Language Name Index 21 Bibliography 22 Copyright © 2017 by SIL International All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, redistributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of SIL International, with the exception of brief excerpts in articles or reviews. Ethnologue: Languages of Honduras 3 List of Abbreviations A Agent in constituent word order alt. alternate name for alt. dial. alternate dialect name for C Consonant in canonical syllable patterns CDE Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960) Class Language classification CPPDCE Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) CSICH Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) dial. -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2019-063 (completed by Registration authority) Date: 2019 Aug 31 Primary Person submitting request: Kirk Miller E-mail address: kirkmiller at gmail dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests Type of change proposed (check one): 1. Modify reference information for an existing language code element 2. Propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group 3. Retire a language code element from use (duplicate or non-existent) 4. Expand the denotation of a code element through the merging one or more language code elements into it (retiring the latter group of code elements) 5. Split a language code element into two or more new code elements 6. Create a code element for a previously unidentified language For proposing a change to an existing code element, please identify: Affected ISO 639-3 identifier: wuu Associated reference name: Wu Chinese 5. Split a language code element into two or more code elements (a) List the languages into which this code element should be split: Taihu Wu Chinese Taizhou Wu Chinese Wuzhou Wu Chinese (Jinqu Wu) Xuanzhou Wu Chinese Chuqu Wu Chinese (Shangli Wu) Oujiang Wu / Ouyu Chinese The highest priority is Oujiang. (b) Referring to the criteria given above, give the rationale for splitting the existing code element into two or more languages: The varieties of Wu are not mutually intelligible. -

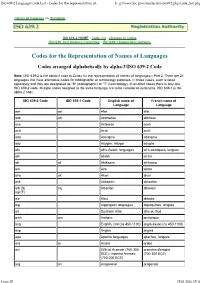

ISO 639-2 Language Code Lis

ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of... h p://www.loc.gov/standards/iso639-2/php/code_list.php Library of Congress >> Standards IS0 639-2 HOME - Code List - Changes to Codes ISO 639 Joint Advisory Committee - ISO 639-1 Registration Authority Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages Codes arranged alphabetically by alpha-3/ISO 639-2 Code Note: ISO 639-2 is the alpha-3 code in Codes for the representation of names of languages-- Part 2. There are 21 languages that have alternative codes for bibliographic or terminology purposes. In those cases, each is listed separately and they are designated as "B" (bibliographic) or "T" (terminology). In all other cases there is only one ISO 639-2 code. Multiple codes assigned to the same language are to be considered synonyms. ISO 639-1 is the alpha-2 code. ISO 639-2 Code ISO 639-1 Code English name of French name of Language Language aar aa Afar afar abk ab Abkhazian abkhaze ace Achinese aceh ach Acoli acoli ada Adangme adangme ady Adyghe; Adygei adyghé afa Afro-Asiatic languages afro-asiatiques, langues afh Afrihili afrihili afr af Afrikaans afrikaans ain Ainu aïnou aka ak Akan akan akk Akkadian akkadien alb (B) sq Albanian albanais sqi (T) ale Aleut aléoute alg Algonquian languages algonquines, langues alt Southern Altai altai du Sud amh am Amharic amharique ang English, Old (ca.450-1100) anglo-saxon (ca.450-1100) anp Angika angika apa Apache languages apaches, langues ara ar Arabic arabe arc Official Aramaic (700-300 araméen d'empire BCE); Imperial Aramaic (700-300 BCE) (700-300 BCE) arg an Aragonese aragonais 1 von 15 15.01.2010 15:16 ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of.. -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2018-011 (completed by Registration authority) Date: 2018-8-9 Primary Person submitting request: Editor Ethnologue Affiliation: SIL International E-mail address: editor_ethnologue at sil dot org Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: Postal address for primary contact person for this request (in general, email correspondence will be used): PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests This form is to be used in requesting changes (whether creation, modification, or deletion) to elements of the ISO 639 Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages. The types of changes that are possible are to 1) modify the reference information for an existing code element, 2) propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group; 3) retire a code element from use, including merging its scope of denotation into that of another code element, 4) split an existing code element into two or more new language code elements, or 5) create a new code element for a previously unidentified language variety. Fill out section 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 below as appropriate, and the final section documenting the sources of your information. The process by which a change is received, reviewed and adopted is summarized on the final page of this form. -

Evaluating Language Statistics: the Ethnologue and Beyond a Report Prepared for the UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Evaluating Language Statistics: The Ethnologue and Beyond A report prepared for the UNESCO Institute for Statistics John C. Paolillo School of Informatics, Indiana University Assisted by Anupam Das Department of Linguistics, Indiana University March 31, 2006 0. Introduction How many languages are there in the world? In a region or a particular country? How many speakers does a given language have? Are there more speakers of English or Mandarin? How are the numbers of these speakers changing, in the world, in a country or on the Internet? Linguists are often asked questions such as these, whether by members of other disciplines, lay-people, or policy makers. Yet despite the interest in and obvious importance of these questions, they are not easy questions to answer, and there are few sources one can turn to for definitive answers. Since the early 1990s, new awareness of a number of language-related issues have foregrounded the need for good answers to these questions. On the one hand, there is the economic trend of globalization, which requires people from a variety of different countries, ethnicities, cultures and language backgrounds to communicate with one another. Globalization has been accompanied by claims about the economic importance of one language vis-a-vis another, and the importance of specific languages in global communication functions or for scientific and cultural exchange. Such discussions have led to re-evaluations of the status of many languages in a range of contexts, such as the role of English globally and in the European Union, and the role of Mandarin Chinese in the Pacific Rim and on the Internet. -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2016-027 (completed by Registration authority) Date: 2016-2-15 Primary Person submitting request: John Livingstone Affiliation: SIL Eurasia E-mail address: cyberspaceplace at yahoo dot co dot uk Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: Richard Gravina, Language Services Director, SIL Eurasia, rcg at btinternet dot com Postal address for primary contact person for this request (in general, email correspondence will be used): John Livingstone, 2 Blackthorn Close, Oxford, OX3 9JF PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests This form is to be used in requesting changes (whether creation, modification, or deletion) to elements of the ISO 639 Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages. The types of changes that are possible are to 1) modify the reference information for an existing code element, 2) propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group; 3) retire a code element from use, including merging its scope of denotation into that of another code element, 4) split an existing code element into two or more new language code elements, or 5) create a new code element for a previously unidentified language variety. Fill out section 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 below as appropriate, and the final section documenting the sources of your information. -

Natural Language Processing: Integration of Automatic and Manual Analysis

Natural Language Processing: Integration of Automatic and Manual Analysis Natürliche Sprachverarbeitung: Integration automatischer und manueller Analyse Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor-Ingenieur (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigte Dissertation von Dipl.-Inform. Richard Eckart de Castilho aus Bensheim 2014 - Fachbereich Informatik — Darmstadt — D 17 Natural Language Processing: Integration of Automatic and Manual Analysis Natürliche Sprachverarbeitung: Integration automatischer und manueller Analyse Genehmigte Dissertation von Dipl.-Inform. Richard Eckart de Castilho aus Bensheim 1. Gutachten: Prof. Dr. Iryna Gurevych, Technische Universität Darmstadt 2. Gutachten: Prof. Dr. Andreas Henrich, Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg 3. Gutachten: Prof. Christopher D. Manning, PhD., Stanford University Tag der Einreichung: 16. Dezember 2013 Tag der Prüfung: 10. Februar 2014 Darmstadt — D 17 Produkte oder Dienstleistungen auf welche in diesem Dokument verwiesen wird können Handels- marken oder eingetragene Handelsmarken der jeweiligen Rechteinhaber seine. Weder der Autor noch der Verlag erheben Ansprüche darauf. Products and services that are referred to in this work may be either trademarks and/or regis- tered trademarks of their respective owners. The author and the publishers make no claim to these trademarks. Bitte zitieren Sie dieses Dokument als: URN: urn:nbn:de:tuda-tuprints-41517 URL: http://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/id/eprint/4151 Dieses Dokument wird bereitgestellt von tuprints, E-Publishing-Service der TU Darmstadt http://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de [email protected] Die Veröffentlichung steht unter folgender Creative Commons Lizenz: Namensnennung – Keine kommerzielle Nutzung – Keine Bearbeitung 3.0 Deutschland http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/de/ To my family. Erklärung zur Dissertation Hiermit versichere ich, die vorliegende Dissertation ohne Hilfe Dritter nur mit den angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmitteln angefertigt zu haben. -

Using Eidr Language Codes

USING EIDR LANGUAGE CODES Technical Note Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommended Data Entry Practice .............................................................................................................. 2 Original Language..................................................................................................................................... 2 Version Language ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Title, Alternate Title, Description ............................................................................................................. 3 Constructing an EIDR Language Code ......................................................................................................... 3 Language Tags .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Extended Language Tags .......................................................................................................................... 4 Script Tags ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Region Tags ............................................................................................................................................. -

Proceedings of the 12Th Workshop on Asian Language Resources (ALR)

ALR 12 The 12th Workshop on Asian Language Resources Proceedings of the Workshop December 12, 2016 Osaka, Japan Copyright of each paper stays with the respective authors (or their employers). ISBN978-4-87974-722-8 ii Preface This 12th Workshop on Asian Language Resources (ALR12) focuses on language resources in Asia, which has more than 2,200 spoken languages. There are now increasing efforts to build multi-lingual, multi-modal language resources, with varying levels of annotations, through manual, semi-automatic and automatic approaches, as the use of ICT spreads across Asia. Correspondingly, the development of practical applications of these language resources has also been rapidly advancing. The ALR workshop series aims to forge a better coordination and collaboration among researchers on these languages and in the NLP community in general, to develop common frameworks and processes for promoting these activities. ALR12 collaborates with ISO/TC 37/SC 4, which develops international standards for "Language Resources Management," and ELRA, which is campaigning LRE map, in order to integrate efforts to develop an Asian language resource map. Also, the workshop is supported by AFNLP, which has a dedicated Asian Language Resource Committee (ARLC), whose aim is to coordinate the important ALR initiatives with different NLP associations and conferences in Asia and other regions. This workshop consists of twelve oral papers and seven posters, plus a special session to introduce ISO/TC 37/SC 4 activities to the community, to stimulate further -

Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages-Part 2: Alpha-3 Code

Codes for the representation of names of languages (Library of Congress) Page 1 of 5 Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages-Part 2: Alpha-3 Code Normative Text 1 Scope This part of ISO 639 provides two sets of three-letter alphabetic codes for the representation of names of languages, one for terminology applications and the other for bibliographic applications. The code sets are the same except for twenty-three languages that have variant language codes because of the criteria used for formulating them (see 4.1). The language codes were devised originally for use by libraries, information services, and publishers to indicate language in the exchange of information, especially in computerized systems. These codes have been widely used in the library community and may be adopted for any application requiring the expression of language in coded form by terminologists and lexicographers. The alpha-2 code set was devised for practical use for most of the major languages of the world that are most frequently represented in the total body of the world's literature. Additional language codes are created when it becomes apparent that a significant body of literature in a particular language exists. Languages designed exclusively for machine use, such as computer programming languages, are not included in this code. 2 Normative reference The following standard contains provisions which, through reference in this text, constitute provisions of this part of ISO 639. At the time of publication, the edition indicated was valid. All standards are subject to revision, and parties to agreements based on this part of ISO 639 are encouraged to investigate the possibility of applying the most recent edition of the standard indicated below.