GEOGRAPHICAL ASSOCIATION of ZIMBABWE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Zimbabwean Government Gazette

A I SET ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. LXXI, No. 44 2nd JULY. 1993 Price $2,50 i General Notice 384 of 1993. Zimbabwe United Passenger Company. ^^0/226/93. Permit: 15723. Motor-omnibus. Passenger-capacity: ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER 262] Route 1: As d^ned in the agreonent between the holder and Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits the Harare Municipality, approved by the Minister in terms of section 18 of the Road Motor Transportation Act [Chapter 262]. IN terms of subsection (4) of section 7 of the Road Motor Transportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that Route 2:' Throu^out Zimbabwe. the applications detailed in the Sdiedule, for ue issue or Route 3: Harare - Darwendale - Banket - Chinhoyi - Aladta amendment of road service permits, have been received for the Compoimd - Sheckleton Mine - lions Den. consideration of the Controller of Road Motor Transportation. Condition: Any person wishing to object to any such application must Route 2: lodge with the Controller of Road Motor Transportation, (a) For private hire and for advertised or organized P.O. Box 8332, Causeway— tours, provided no stage carriage service is operated (a) a notice, in writing, of his intention to object, so as along any route. to reach the Controller’s ofiSce not later than the 23rd (b) No private Hire or any advertised or organized tour July, 1993; shall be operated under authority of this permit, (b) his objection and the grounds therefor, on form RAl.T. during ^e times for which a scheduled stage carriage 24, together with two copies tiiereof, so as to tetaxHa. -

Information on Zimbabwe Project Site

Global Mercury Project Project EG/GLO/01/G34: Removal of Barriers to Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies Information about the Project Sites in Zimbabwe Dennis S. M. Shoko, PhD Assistant to Country Focal Point, GMP-Zimbabwe Marcello M. Veiga, PhD Small-scale Mining Expert, GMP - Vienna January 2004 Table of Content Page 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................3 2. Description of the Site................................................................................................................3 2.1. Physiography (relief and drainage).....................................................................................3 2.2. Outline Geology of the Area ...............................................................................................6 2.3. Climate (temperatures and rainfall) ....................................................................................6 2.4. Access and Infrastructure.....................................................................................................7 2.5. Administrative and Institutional Structures........................................................................7 2.6. History of Gold Extraction in the Chakari-Golden Valley Area.......................................8 2.7. Community Socio-economic Profile...................................................................................8 2.7.1. Demographic Data .......................................................................................................8 -

Observations on Agro-Ecology Post Cyclone Idai 3/24/19 Hi Friends, John Wilson Is Based in Southern Africa. This Note to Some Of

Observations on Agro-Ecology post Cyclone Idai 3/24/19 Hi Friends, John Wilson is based in southern Africa. This note to some of his partners and farmers in the region reflects on the horrors in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai, lessons learned about agroecology, forest cover, and nature-based water management, and the role of "evidence based practices" in this context. An important read for all of us as so many face unspeakable displacement and loss. John makes a strong case for supporting agroecological groups and methods even when all the peer reviewed science is not yet in. This is a tension among us - when must we wait for 5 or 10 year studies to demonstrate impacts given an IPCC report that gives us 10 years to transform our energy and agricultural systems? When do we look, listen and adapt complex systems based on local farmer and community knowledge? What is the role of "humility" in indigenous knowledge and among those claiming outcomes without peer reviewed verification? How do we maintain a collective spirit of inquiry and mutual respect for different ways of knowing? How do we act now with limited and imperfect yet compelling evidence/knowledge for a range of complex practices? John raises very important questions and concerns. Betsy === John Wilson’s original letter: From: John Wilson <[email protected]> Subject: Chimanimani, evidence and patience (or lack of??!) Date: 23 March 2019 at 11:56:00 GMT+2 To: Afsafrica <[email protected]>, abn partners-allies <abn-partners- [email protected]> Dear All – A reflective letter from Zimbabwe after a very difficult week. -

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

Urban Women's Participation in the Construction Industry: an Analysis

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 9 | Issue 3 Article 14 May-2008 Urban Women’s Participation in the Construction Industry: An Analysis of Experiences from Zimbabwe Edward Mutandwa Noah Sigauke Charles P. Muganiwa Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mutandwa, Edward; Sigauke, Noah; and Muganiwa, Charles P. (2008). Urban Women’s Participation in the Construction Industry: An Analysis of Experiences from Zimbabwe. Journal of International Women's Studies, 9(3), 256-268. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol9/iss3/14 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2008 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Urban Women’s Participation in the Construction Industry: An Analysis of Experiences from Zimbabwe By Edward Mutandwa1, Noah Sigauke2 and Charles P. Muganiwa3 Abstract This paper analyzed the impact of urban women’s participation in the construction business on income generation, gender roles and responsibilities, family and societal perceptions in Zimbabwe. Problems and constraints affecting women’s participation in the sector were also identified. A total of 130 respondents were purposively selected from four urban cities namely Chitungwiza, Marondera, Norton and Rusape. Structured questionnaires and focus group discussions were used as the main data collection instruments. -

PLAAS RR46 Smeadzim 1.Pdf

Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Report 46 Space, Markets and Employment in Agricultural Development: Zimbabwe Country Report Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Published by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Email: [email protected] Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research Report no. 46 June 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher or the authors. Copy Editor: Vaun Cornell Series Editor: Rebecca Pointer Photographs: Pamela Ngwenya Typeset in Frutiger Thanks to the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) and the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Growth Research Programme Contents List of tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................. iii Acronyms and abbreviations ...................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ -

"Our Hands Are Tied" Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe – Nov

“Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-404-4 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2008 1-56432-404-4 “Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe I. Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................... 5 To the Future Government of Zimbabwe .............................................................. 5 To the Chief Justice ............................................................................................ 6 To the Office of the Attorney General .................................................................. 6 To the Commissioner General of the Zimbabwe Republic Police .......................... 6 To the Southern African Development Community and the African Union ........... -

38678 10-4 Roadcarrierp Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA Vol. 598 Pretoria, 10 April 2015 No. 38678 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 501272—A 38678—1 2 No. 38678 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 10 APRIL 2015 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 38678 Menlyn..................................................... 3 38678 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke aangaande Bedryfslisensies:. -

Blue Swallow Survey Report November

Blue Swallow Survey Report November 2013- March 2014 By Fadzai Matsvimbo (BirdLife Zimbabwe) with assistance from Tendai Wachi ( Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority) Background The Blue Swallow Hirundo atrocaerulea is one of Africa’s endemics, migrating between East and Central to Southern Africa where it breeds in the summer. These breeding grounds are in Zimbabwe, South Africa, Swaziland, Mozambique, Malawi, southern Tanzania and south eastern Zaire, Zambia. The bird winters in northern Uganda, north eastern Zaire and Western Kenya (Keith et al 1992).These intra-african migrants arrive the first week of September and depart in April In Zimbabwe (Snell 1963.).There are reports of the birds returning to their wintering grounds in May (Tree 1990). In Zimbabwe, the birds are restricted to the Eastern Highlands where they occur in the Afromontane grasslands. The Blue Swallow is distributed from Nyanga Highlands southwards through to Chimanimani Mountains and are known to breed from 1500m - 2200m (Irwin 1981). Montane grassland with streams forming shallow valleys and the streams periodically disappearing underground and forming shallow valleys is the preferred habitat (Snell 1979). Whilst birds have been have only ever been located in the Eastern Highlands there is a solitary record from then Salisbury now Harare (Brooke 1962). The Blue Swallow is a medium sized swallow of about 20- 25 cm in body length. The males and females can be told apart by the presence of the long tail retrices in the male. The tail streamers in the males measure twice as long as the females (Maclean 1993). The adults are a shiny blue-black with a black tail with blue green gloss and whitish feather shafts. -

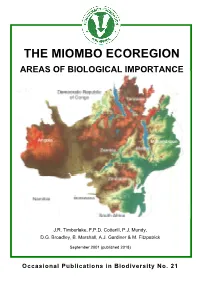

The Miombo Ecoregion Areas of Biological Importance

THE MIOMBO ECOREGION AREAS OF BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE J.R. Timberlake, F.P.D. Cotterill, P.J. Mundy, D.G. Broadley, B. Marshall, A.J. Gardiner & M. Fitzpatrick September 2001 (published 2018) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 21 THE MIOMBO ECOREGION: AREAS OF BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE J.R. Timberlake, F.P.D. Cotterill, P.J. Mundy, D.G. Broadley†, B. Marshall, A.J. Gardiner & M. Fitzpatrick September 2001 (revised February 2018) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 21 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe Miombo Ecoregion: Areas of Biological Importance, page 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The maps were produced at the request of the Southern Africa Programme Office of the WorldWide Fund for Nature (WWF SARPO) under their Miombo Ecoregion project, funding for which was provided by WWF US. Particular thanks are due to the Regional Representative, Harrison Kojwang, and to the Programme Officer, Fortune Shonhiwa, who ran the project. We also wish to thank Heather Whitham in the Biodiversity Foundation for Africa for administrative support. The GIS versions of the maps, originally drawn manually, were digitised at the University of Botswana's Harry Oppenheimer Okavango Research Centre in Maun, Botswana, with financial support from Conservation International through their Wilderness Programme. Particular thanks are due to Mike Murray-Hudson and Leo Braak for making this possible. Final GIS maps were designed, drawn and checked by Ed Lim (Eastbourne, UK). Each map was compiled by a BFA specialist, with the