Iran. a Study of the Automotive Market And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Membranske Crpalke Za Napajanje

Membranske crpalke za napajanje motorjev z nafto ali bencinom pompe a diaframma per il combustibile, per l’alimentazione dei motori diesel o benzina diaphragm fuel pumps for feeding diesel or gasoline motors Kraftstoffmembranpumpen fur diesel und benzin motoren PTZ d.o.o. Proizvodnja trgovina zastopnistvo - proizvodnja membranskih crpalk za gorivo in hladilno tekocino produzione commercio reppresentanza - produzione pompe a diaframma per il combustibile per motori e liquidi refrigeranti production trade representation - production of diaphragm fuel pumps and cooling liquids produktion handlung vertretung - membranpumpen produktion fur kraftstofe und kuelflussigkeit 6 7 Alphabetical list of pumps fuel pumps for vehicles BENZIN BENZIN BENZIN BENZIN PTZ PTZ PTZ PTZ PTZ PTZ PUMP number page PUMP number page PUMP number page PUMP number page PUMP number page PUMP number page ALFA ROMEO BEDFORD AUSTIN ALLEGRO 1500/1750 3456 54 4471 79 VISA SUPER GT 3293 36 SUNNY 1.3 (B 11) (E 13 S ENG.) OHC 4590 96 2000 3003 24 BEAGLE ESTA TE CAR 3382 43 AUSTIN ALLEGRO 1500/1750 - HL - SPOR... 3423 49 CITROEN VISA, VISA II SPECIAL 3241 32 SUNNY 1.5 (B 11) E 15 S ENG.) OHC 4590 96 1750, 2000 3002 24 CHEVANNE 3386 43 AUSTIN ALLEGRO METRO 3432 50 2 CV 3240 31 XM 2.0 OHC 112/91 - 92 4620 100 SUNNY 1.6 (B 12, N 13) (E 16 ENG.) OHC 4598 97 33 1300 - 1600 3449 53 CHEVANNE 76 3446 52 AUSTIN LM 11 4532 88 2 CV 4, 2 CV 6, 2 CV SPECIAL 3241 32 XM 2.0 OHC 9/89 - 12/91 4618 100 SUNNY VAN 1.3 (B 11) (E 13 S ENG.) OHC 4590 96 33, 33 S 3007 24 HA FURGANE B/8 CWT. -

Elstar Mechanical Fuel Pumps Cross Ref And

ELSTAR s.r.l. Mechanical Fuel Pumps - Pompe Carburante meccaniche Mechanical Fuel Pumps - Pompe Carburante meccaniche >> Cross Reference and Applications ELSTAR MAKE OEM MODEL CC. YEAR 1 FP 3002 ALFA ROMEO 101.100402100 1750, 2000 1750, 2000 - 2 105.000402000 A 11-A 12 Furgone - - 3 105.000402001 Alfa 75 (Tutti i tipi) 1600,1800, 2000 1988-1989 4 105.120402000 Alfa Spider 1600, 2000 - 5 105.440402000 Alfetta 1600, 1800, 2000 1976-1979 6 25066445 461-1 F 11-F 12 Furgone - - 7 POC 065 Giulia GT, TI -Super 1300,1600 - 8 Giulietta 1300 1980-1983 9 FP 3003 ALFA 105.1204.020.00 2000 10 FP 3007 ALFA ROMEO 00605 0421400 Alfa 33, 33 S 1351, 1490, 1712 1983-1990 11 25066444 Alfa Sud Sprint, Veloce 1.3 -1.5 Lit. 1977... 12 461-7 Aifa Sud, TI 1200, 1300, 1500,1700 1973... 13 510 737 531 354 Arna (Tutti i tipi) - - 14 542 140 15 5507929 16 7.21775.50 17 8631 18 9.06.130.11 19 BC-138 20 POC 050 21 FP 3008 ALFA ROMEO 116.0804.020.04 Giulietta 1300 -1600 -1800 22 116.0804.020.06 Alfeta 2000 -Alfa 90 77- 23 116.080.402.005 24 FP 3019 AUTOBIANCHI 25066483 A 112 Abarth 1050 -70 HP 1979-1984 25 4250477 Y 10 Touring, Turbo 1050 1985-1988 26 FIAT 4365252 127 (Tutti i tipi) 1050 - 27 4427880 Duna 60, 70 1100,1300 1987-1990 28 4434835 Fiorino, Pick-up 1050 1979-1988 29 4452648 Ritmo 60 L 1050 - 30 FIAT (Argentina) 461-11 Duna 1300,1500 - 31 60338 Europa 1300 - 32 60339 Regatta 85 Weekend - - 33 7703714 Spazio 1100,1300 - Mechanical Fuel Pumps - Pompe Carburante meccaniche >> Cross Reference and Applications ELSTAR MAKE OEM MODEL CC. -

Saudis Seeking to Undermine Nuclear Deal Benefits: Larijani

Zarif: Shia and South Pars daily output FIBA Asia U18 Iran’s first 21112Sunni are both victims 4 to rise to 540mcm Championship: Iran virtual art gallery NATION of terrorism ECONOMY by Mar. 2017 SPORTS beaten by Japan ART& CULTURE launched WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y Iran to protest IAEA over leak of confidential documents 2 12 Pages Price 10,000 Rials 38th year No.12607 Monday JULY 25, 2016 Mordad 4, 1395 Shawwal 20, 1437 Banking Saudis seeking to undermine reform bills in Majlis by nuclear deal benefits: Larijani mid-August: Majlis speaker says what Saudis are doing is ‘open hostility’ CBI governor POLITICAL TEHRAN — Iranian Par- tain Western countries are taking “obstructive” sanctions on Iran. not be able to use the post-nuclear deal condi- deskliament Speaker Ali Larijani measures to prevent Iran from benefiting the “Evils of Saudis and certain Western coun- tions,” Larijani told a gathering in Qom, the city ECONOMY TEHRAN - Two pro- desk said on Saturday that Saudi Arabia and cer- advantages of the nuclear deal which removes tries have created obstacles so that Iran would which he represents in the Majlis. 2 posed bills aiming at banking system reform have been pre- pared and will be sent to the parliament (Majlis) by the end of the current Iranian calendar month of Mordad (August 21), First IRNA quoted Central Bank Governor Valiollah Seif as saying on Sunday. Kiarostami “The two bills have been drafted in line with the country’s financial and prize awarded monetary reform plan and after being approved by the government they will to “Fish and be presented to Majlis,” he added. -

British V8 Newsletter (Aka MG V8 Newsletter)

California Dreaming: an MGB-GT-V8 on Route 66 (owners: Robert and Susan Milner) The British V8 Newsletter - Current Issue - Table of Contents British V8 Newsletter May - September 2007 (Volume 15, Issue 2) 301 pages, 712 photos Main Editorial Section (including this table of contents) 45 pages, 76 photos In the Driver's Seat by Curtis Jacobson Canadian Corner by Martyn Harvey How-to: Under-Hood Eaton M90 Supercharger on an MGB-V8! by Bill Jacobson How-to: Select a Performance Muffler by Larry Shimp How-to: Identify a Particular Borg-Warner T5 Transmission research by David Gable How-to: Easily Increase an MGB's Traction for Quicker Launches by Bill Guzman Announcing the Winners - First Annual British V8 Photo Contest by Robert Milks Please Support Our Sponsors! by Curtis Jacobson Special Abingdon Vacation Section: 51 pages, 115 photos Abingdon For MG Enthusiasts by Curtis Jacobson A Visit to British Motor Heritage (to see actual MG production practices!) by Curtis Jacobson The Building of an MG Midget Body by S. Clark & B. Mohan BMH's Exciting New Competition Bodyshell Program by Curtis Jacobson How BMH Built a Brand-New Vintage Race Car by Curtis Jacobson Special Coverage of British V8 2007: 67 pages, 147 photos British V8 2007 Meet Overview by Curtis Jacobson British V8 Track Day at Nelson Ledges Road Course by Max Fulton Measuring Up: Autocrossing and Weighing the Cars by Curtis Jacobson Valve Cover Race Results by Charles Kettering Continuing Education and Seminar Program Tech Session 1 - Digital Photography for Car People (with Mary -

Collectors' Motor Cars & Automobilia

Monday 29 April 2013 The Royal Air Force Museum London Collectors’ Motor Cars & Automobilia Collectors’ Motor Cars and Automobilia The Monday 29 April 2013 at 11am and 2pm RAF Museum Hendon London, NW9 5LL Sale Bonhams Bids Enquiries Customer Services 101 New Bond Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Motor Cars Monday to Friday 8am to 6pm London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 bonhams.com To bid via the internet please +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax visit www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder information including after-sale Viewing Please note that bids should be collection and shipment Sunday 28 April 10am to 5pm submitted no later than 4pm on Automobilia Monday 29 April from 9am Friday 26 April. Thereafter bids +44 (0) 8700 273 618 Please see back of catalogue should be sent directly to the +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax [email protected] for important notice to bidders Sale times Bonhams office at Hendon on +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax Automobilia 11am Motor Cars 2pm Enquiries on view Sale Number: 20926 We regret that we are unable to and sale days accept telephone bids for lots with Live online bidding is a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 available for this sale Absentee bids will be accepted. +44 (0) 08700 270 089 fax Illustrations Please email [email protected] New bidders must also provide Front cover: Lot 350 with “Live bidding” in the subject proof of identity when submitting Catalogue: £25 + p&p Back cover: Lot 356 line 48 hours before the auction bids. -

The Magazine Of

No.56 - SUMMER 2012 THE MAGAZINE OF Leyland cover T56.indd 1 1/6/12 17:33:01 Hon. PRESIDENT Andrea Thompson, Managing Director, Leyland Trucks Ltd. Hon. VICE PRESIDENTS Gordon Baron, 44 Rhoslan Park, 76 Conwy Road, Colwyn Bay LL29 7HR Neil D. Steele, 18 Kingfi sher Crescent, Cheadle, Staffordshire, ST10 1RZ CHAIRMAN, BCVM LIAISON Ron Phillips, 16 Victoria Avenue, ‘FLEET BOOKS’ EDITOR Grappenhall, Warrington, WA4 2PD EDITOR and SECRETARY Mike A Sutcliffe MBE, ‘Valley Forge’ 213 Castle Hill Road, Totternhoe, Dunstable, Beds LU6 2DA MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY David J. Moores, 10 Lady Gate, Diseworth, Derby DE74 2QF TREASURER David E.Berry, 40 Bodiam Drive, VEHICLE REGISTRAR Toothill, Swindon, Wilts, SN5 8BE WEBMASTER John Woodhouse, contact via David Bishop WEBSITE & NEW MEMBERS David L. Bishop, ‘Sunnyside’ Whitchurch Road, Aston, Nantwich, CW5 8DB TECHNICAL & SPARES Don Hilton, 79 Waterdell, Leighton Buzzard, Beds. LU7 3PL EVENT COORDINATOR Gary Dwyer, 8 St Mary’s Close, West St. Sompting, Lancing, W. Sussex BN15 0AF COMMITTEE MEMBER John Howie, 37 Balcombe Gardens, Horley, Surrey, RH6 9BY COMMITTEE MEMBER Terry Spalding, 5 Layton Avenue, Mansfi eld, Notts. NG18 5PJ MEMBERSHIP Subscription levels are £27 per annum (Family £31), £33 for EEC members, £38 (in Sterling) for membership outside the EEC. Anyone joining after 1st April and before 31st July will have their membership carried over to the next 31st July, ie up to 16 months. This is good value for money and new members are welcomed. Application forms are available from the Membership Secretary or via the Website www.leylandsociety.co.uk Leyland cover T56.indd 2 1/6/12 17:33:02 Issue No. -

"F~;;;~~Iz~UTOMOTIVE HISTORY REVIEW

"f~;;;~~iZ~UTOMOTIVE HIstorIans HISTORY SUMMER 1986 ISSUE NO. 20 REVIEW A PUBLICATION OF THE SOCIETY OF AUTOMOTIVE HISTORIANS, INC. AUTOMOTIVE HISTORY EDITOR _SUMM_ER198_6 -REVIE",X7 Richard B. Brigham ISSUE NUMBER 20 •• ~ All correspondence in connection with Automotive History Review should be A Car That Never Was Front Cover addressed to: Society of Automotive This is a reproduction of the cover of a dummy brochure sent by a chap in California to Keith Marvin, by way of Nick Georgano. Historians, Printing & Publishing This flyer was obviously hand-drawn, and lacks both text and Office, 1616 Park Lane, N.E., Marietta, illustrations. When it was made-and where and by whom-are Georgia 30066. questions without answers, but see pages 4 and following. Editorial Comment 3 At the risk of seeming repetitious, we continue to write about the appalling lack of accuracy to be found in many of the ref- erence sources available to those who write automotive history. In this one -issue, two widely differing sources of mis-informa- Automotive History Review is a tion are presented-sources which would seem to be reliable. semi-annual publication of the Society The Phantom of Cincinnati 4 of Automotive Historians, Inc. Type- This "prototype" brqchure, devoid of text or pictures save for the setting and layout is by Brigham Books, drawing on the front cover, was discovered by SAH member Steve Marietta, Georgia 30066. Printing is Richmond while he was rummaging through a flea market in Cali- fornia. Apparently no records exist of an Eagle car being made in by Brigham Press, Inc., 1950 Canton Cincinnati, Ohio, and the brochure is assumed to be a practice Road, N.·E., Marietta, Georgia 30066. -

March / April 2018 Issue

SAHJournal ISSUE 291 MARCH / APRIL 2018 SAH Journal No. 291 • March / April 2018 $5.00 US1 Contents 3 PRESIDENT’S PERSPECTIVE SAHJournal 4 CENTURY OF AUSTRALIAN AUTOMOBILE MANUFACTURE ENDS ISSUE 291 • MARCH/APRIL 2018 A HISTORICAL REVIEW AND PERSPECTIVE 8 SAH IN PARIS XXIII THE SOCIETY OF AUTOMOTIVE HISTORIANS, INC. 9 RÉTROMOBILE 43 An Affiliate of the American Historical Association 11 BOOK REVIEWS Billboard Officers Louis F. Fourie President SAH Board Nominations: related to Rolls-Royce of America, Inc. This Edward Garten Vice President Robert Casey Secretary The SAH Nominating Committee is includes promotional images of Rolls-Royce Rubén L. Verdés Treasurer seeking nominations for positions on the automobiles photographed by John Adams board through 2021. Please address all Davis. Other automotive history subjects Board of Directors nominations to the chair, Andrew Beckman are sought too. Only digital images are Andrew Beckman (ex-officio) ∆ Robert G. Barr ∆ at [email protected]. needed. Accordingly, if you would like your H. Donald Capps # antique automotive documents and photos Donald J. Keefe ∆ Wanted: Contributors! The SAH digitized for free, just contact the editor at Kevin Kirbitz # Journal invites contributors for articles and [email protected] to confirm the assign- Carla R. Lesh † book reviews. (A book reviewer that can read ment. Then mail your material, and it will be John A. Marino # Robert Merlis † Japanese is currently needed.) Please contact mailed back to you with the digital media. Matthew Short ∆ the editor directly. Thank you! Vince Wright † Your Billboard: What are you Terms through October (†) 2018, (∆) 2019, and (#) 2020 Correction: The masthead of issues working on?.. -

LEYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY (Founded 1968) Registered Charity No

LEYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY (Founded 1968) Registered Charity No. 1024919 PRESIDENT Mr W E Waring CHAIR VICE-CHAIR Mr P Houghton Mrs E F Shorrock HONORARY SECRETARY HONORARY TREASURER Mr M J Park Mr E Almond (01772) 337258 AIMS To promote an interest in History generally and that of the Leyland area in particular MEETINGS Held on the first Monday of each month (September to July inclusive) at 7.30 pm (Meeting date may be amended by statutory holidays) in The Shield Room, Banqueting Suite, Civic Centre West Paddock, Leyland SUBSCRIPTIONS £10.00 per annum Vice Presidents £8.00 per annum Members £0.50 per annum School Members £2.00 per meeting (except where indicated Casual Visitors on programme) A MEMBER OF THE LANCASHIRE LOCAL HISTORY FEDERATION THE HISTORIC SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE and THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR LOCAL HISTORY Visit the Leyland Historical Society’s Website at http/www.houghton59.fsnet.co.uk/Home%20Page.htm Lailand Chronicle No. 53 2 Lailand Chronicle No. 53 Contents Page Title Contributor 4 Editorial Mary Longton 5 Chairman’s Report 2006 - 2007 Peter Houghton 9 The Book Review Peter Houghton 10 More about Wymott Derek Wilkins 14 Ambrye Meadow Field Stones Ian Barrow 18 Leyland Motors’ Sports – Part Two Edward Almond 29 18th Century Rejoicing Derek Wilkins 33 Golden Hill Lane in the ‘forties Sylvia Thompson Did you know my great-great-great-grandfather 42 Peter Houghton on my mother’s side? 49 James Sumner’s Resting Place Stanley Haydock 54 Cuerden Hall Auxiliary Hospital Joan Langford 61 Old Leyland Parish Church Magazines Sylvia Thompson 62 Obituary – Mr Frank Cumpstey 3 Lailand Chronicle No. -

P&A Plants A4 2013 by MANUFACTURER Web

AUTOMOBILE ASSEMBLY & ENGINE PRODUCTION PLANTS IN EUROPE BY MANUFACTURER Type produced Plant location Manufacturer Brand Engine PC LCV CV Bus ACEA MEMBERS BMW GROUP AT-Austria Steyr BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Dingolfing BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Leipzig BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Munich BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Regensburg BMW GROUP BMW UK-United Kingdom Cowley (Oxford) BMW GROUP Mini UK-United Kingdom Goodwood BMW GROUP Rolls Royce UK-United Kingdom Hams Hall BMW GROUP Facilities not owned / operated by BMW AT-Austria Graz BMW GROUP Mini at MAGNA STEYR plant NL-Netherlands Born BMW GROUP Mini at VDL plant (from 2014) RU-Russia Kaliningrad BMW GROUP BMW at AVTOTOR plant DAF TRUCKS NV BE-Belgium Westerlo DAF TRUCKS NV DAF NL-Netherlands Eindhoven DAF TRUCKS NV DAF UK-United Kingdom Leyland DAF TRUCKS NV DAF DAIMLER AG DE-Germany Affalterbach DAIMLER AG AMG DE-Germany Berlin DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Bremen DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Dortmund DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz minibuses DE-Germany Düsseldorf DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, for VOLKSWAGEN DE-Germany Kölleda DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Ludwigsfelde DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, for VOLKSWAGEN DE-Germany Mannheim DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz (truck engines), Setra (JV KAMAZ) DE-Germany Neu-Ulm DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Rastatt DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Sindelfingen DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Untertürkheim (Stuttgart) DAIMLER AG DE-Germany Wörth DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, Unimog ES-Spain Samano DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz ES-Spain Vitoria DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz -

The Triumph Trumpet Is the Magazine of the Triumph Car Club of Victoria, Inc

March 2019 TrThue mpet The Triumph Car Club of Victoria Magazine General Meetings are held monthly on the third Wednesday of the month, except for the month of December and the month in which an AGM is held. The standard agenda for the General Meetings is: • Welcome address • Guest Speaker / Special Presentations • Apologies, Minutes & Secretary’s Report • Treasurer’s Report • Editor’s Report • Event Coordinator’s Report • Membership Secretary’s Report • Library, Tools & Regalia Report • Triumph Trading Report • AOMC Report • Any other business. The order of the agenda is subject to alteration on the night by the chairman. Extra agenda items should be notified to the attention of the Secretary via email to [email protected] The minutes of monthly general meetings are available for reference in the Members Only section of the website. A few hard copies of the prior month’s minutes will be available at each monthly meeting for reference. Please email any feedback to the Secretary at [email protected] The Triumph Trumpet is the magazine of the Triumph Car Club of Victoria, Inc. (Reg. No. A0003427S) Front Cover Photograph 2 Editorial 3 Upcoming Events! 4 Smoke Signals 5 The Triumph Car Club of Victoria is a Great Australian Rally/Cruden Farm 67 participating member of the Association Drive Your Triumph Day 812 of Motoring Clubs. Member Profile – Ryan Pillay 1314 The TCCV is an Authorised Club under Power Steering 1516 the VicRoads Club Permit Scheme. Harry & the European Connections1617 History of Lucas Electrics 1826 Articles in the Triumph Trumpet may be quoted without permission, however, due acknowledgment must be made. -

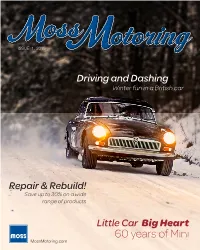

60 Years of Mini Mossmotoring.Com REPAIR & REBUILD IT's TIME to GET SAVE % SALE VALID 1/7– 2/1/19 SALE UPYOUR to HANDS30 DIRTY

ISSUE 1, 2019 Driving and Dashing Winter fun in a British car Repair & Rebuild! Save up to 30% on a wide range of products Little Car Big Heart 60 years of Mini MossMotoring.com REPAIR & REBUILD IT'S TIME TO GET SAVE % SALE VALID 1/7– 2/1/19 SALE UPYOUR TO HANDS30 DIRTY Come See Some Old Friends June 8 – Petersburg, Virginia Learn more about Motorfest and register at MossMotors.com/Motorfest Motorfest is more than a car show. It’s a • British Sports Car Show & Awards fun sports car reunion with friends from all • Mazda Miata Show & Awards A Great over the country, good food you don’t have to • Moss Warehouse Tours Summer cook, and the doors of Moss Motors are open • Bounce House For the Kids to you. We can’t wait to show you around! • Music Dj, Vendor Booths, and More! Event! BRAKES // COOLING CHECK OUT THE INSERT INSIDE ▷ FUEL // WIRING HARNESSES 4 9 12 16 Warm Winter Mini Turns 60 Safety Fast! Mini 1275 GTS Memories Learn about the origins of Inspection For a time, South Africa one of the most iconic and built perhaps the best Mini For most, snow and British Leave your worries delightful cars ever made. of them all. cars do not mix. Ever. But (and your excuses) behind. that wasn't always the case. On the Cover: there's more online! The tip of the iceberg. That’s what you're holding in your hands. Rytis Petrauskas from Lithuania The MossMotoring.com archive is chock full of stories and a wealth of technical piloted his 1965 MGB the past two advice.