The Development of Emotion in Ancient Greek Sculpture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating the Past: Roman Villa Sculptures

��������������������������������� Creating the Past: Roman Villa Sculptures Hadrian’s pool reflects his wide travels, from Egypt to Greece and Rome. Roman architects recreated old scenes, but they blended various elements and styles to create new worlds with complex links to ideal worlds. Romans didn’t want to live in the past, but they wanted to live with it. Why “creating” rather than “recreating” the past? Most Roman sculpture was based on Greek originals 100 years or more in the past, but these Roman copies, in their use & setting, created a view of the past as the Romans saw it. In towns, such as Pompeii, houses were small, with little room for large gardens (the normal place for statues), so sculpture was under life-size and highlighted. The wall frescoes at Pompeii or Boscoreale (as in the reconstructed room at the Met) show us what the buildings and the associated sculptures looked like. Villas, on the other hand, were more expansive, generally sited by the water and had statues, life-size or larger, scattered around the gardens. Pliny’s villas, as he describes them in his letters, show multiple buildings, seemingly haphazardly distributed, connected by porticoes. Three specific villas give an idea of the types the Villa of the Papyri near Herculaneum (1st c. AD), Tiberius’ villa at Sperlonga from early 1st century (described also in CHSSJ April 1988 lecture by Henry Bender), and Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli (2nd cent AD). The Villa of Papyri, small and self-contained, is still underground, its main finds having been reached by tunneling; the not very scientific excavation left much dispute about find-spots and the villa had seen upheaval from the earthquake of 69 as well as the Vesuvius eruption of 79. -

A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Faculty Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Research and Scholarship 1974 A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S. Ridgway Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Ridgway, Brunilde S. 1974. A Story of Five Amazons. American Journal of Archaeology 78:1-17. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Story of Five Amazons* BRUNILDE SISMONDO RIDGWAY PLATES 1-4 THEANCIENT SOURCE dam a sua quisqueiudicassent. Haec est Polycliti, In a well-knownpassage of his book on bronze proximaab ea Phidiae, tertia Cresilae,quarta Cy- sculpturePliny tells us the story of a competition donis, quinta Phradmonis." among five artists for the statue of an Amazon This texthas been variously interpreted, emended, (Pliny NH 34.53): "Venereautem et in certamen and supplementedby trying to identifyeach statue laudatissimi,quamquam diversis aetatibusgeniti, mentionedby Pliny among the typesextant in our quoniamfecerunt Amazonas, quae cum in templo museums. It may thereforebe useful to review Dianae Ephesiaedicarentur, placuit eligi probatis- brieflythe basicpoints made by the passage,before simam ipsorum artificum, qui praesenteserant examining the sculpturalcandidates. iudicio,cum apparuitearn esse quam omnes secun- i) The Competition.The mention of a contest * The following works will be quoted in abbreviated form: von Bothmer D. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

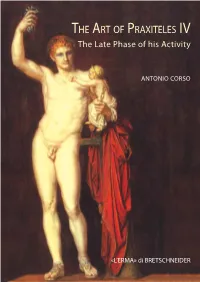

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

On April 20Th, Dr. Anja Slaw

“How fast does a city recover from destruction? A new view of the creation of the Severe Style” On April 20th, Dr. Anja Slawisch, a research fellow at University of Cambridge, presented her careful reconsideration of the transition from Archaic period to Classical period in art, especially in sculpture. I will first give some historical background and conventional understanding of this transition, and then elaborate on her argument. Conventionally, the sack of Athens during the Persian War in 480 BCE spurred the artistic development from austere Archaic style (see statues of Kleobis and Biton below1) to the Severe Style (see Harmodius and Aristogeiton, the tyrannicides2), and hence marks the transition from Archaic period into Classical period in art. The most important feature that sets severe style apart from the Archaic is a more naturalistic depiction of the human anatomy. For statues of the tyrannicides, the human bodies were made as an organic system - their pelves shift according to their stances, as opposed to the awkward posture of Kleobis and Biton. In this widely-accepted narrative, the destruction of Athens, heavily influencing the psyche of Athenians, stimulated these stark changes and inventions in artistic style. As a consequence, 480 BCE became a reference point for archaeologists in dating these statues according to their features. Statues of Kleobis and Biton Harmodius and Aristogeiton 1 Statues of Kleobis and Biton (identified by inscriptions on the base) dedicated to Delphi by the city of Argos, signed by [Poly?]medes of Argos. Marble, ca. 580 BC. H. 1.97 m (6 ft. 5 ½ in.), after restoration. -

Greek Culture

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE GREEK CULTURE Course Description Greek Culture explores the culture of ancient Greece, with an emphasis on art, economics, political science, social customs, community organization, religion, and philosophy. About the Professor This course was developed by Frederick Will, Ph.D., professor emeritus from the University of Iowa. © 2015 by Humanities Institute Course Contents Week 1 Introduction TEMPLES AND THEIR ART Week 2 The Greek Temple Week 3 Greek Sculpture Week 4 Greek Pottery THE GREEK STATE Week 5 The Polis Week 6 Participation in the Polis Week 7 Economy and Society in the Polis PRIVATE LIFE Week 8 At the Dinner Table Week 9 Sex and Marriage Week 10 Clothing CAREERS AND TRAINING Week 11 Farmers and Athletes Week 12 Paideia RELIGION Week 13 The Olympian Gods Week 14 Worship of the Gods Week 15 Religious Scepticism and Criticism OVERVIEW OF GREEK CULTURE Week 16 Overview of Greek Culture Selected collateral readings Week 1 Introduction Greek culture. There is Greek literature, which is the fine art of Greek culture in language. There is Greek history, which is the study of the development of the Greek political and social world through time. Squeezed in between them, marked by each of its neighbors, is Greek culture, an expression, and little more, to indicate ‘the way a people lived,’ their life- style. As you will see, in the following syllabus, the ‘manner of life’ can indeed include the ‘products of the finer arts’—literature, philosophy, by which a people orients itself in its larger meanings—and the ‘manner of life’ can also be understood in terms of the chronological history of a people; but on the whole, and for our purposes here, ‘manner of life’ will tend to mean the way a people builds a society, arranges its eating and drinking habits, builds its places of worship, dispenses its value and ownership codes in terms of an economy, and arranges the ceremonies of marriage burial and social initiation. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Greek Bronze Yearbook of the Irish Philosophical Society 2006 1

Expanded reprint Greek Bronze 1 In Memoriam: John J. Cleary (1949-2009) Greek Bronze: Holding a Mirror to Life Babette Babich Abstract: To explore the ethical and political role of life-sized bronzes in ancient Greece, as Pliny and others report between 3,000 and 73,000 such statues in a city like Rhodes, this article asks what these bronzes looked like. Using the resources of hermeneutic phenomenological reflection, as well as a review of the nature of bronze and casting techniques, it is argued that the ancient Greeks encountered such statues as images of themselves in agonistic tension in dynamic and political fashion. The Greek saw, and at the same time felt himself regarded by, the statue not as he believed the statue divine but because he was poised against the statue as a living exemplar. Socrates’ Ancestor Daedalus is known to most of us because of the story of Icarus but readers of Plato know him as a sculptor as Socrates claims him as ancestor, a genealogy consistently maintained in Plato’s dialogues.1 Not only is Socrates a stone-cutter himself but he was also known for his Daedalus-like ingenuity at loosening or unhinging his opponent’s arguments. When Euthyphro accuses him of shifting his opponents’ words (Meletus would soon make a similar charge), Socrates emphasizes this legacy to defend himself on traditionally pious grounds: if true, the accusation would set him above his legendary ancestor. Where Daedalus ‘only made his own inventions to move,’ Socrates—shades of the fabulous Baron von Münchhausen—would thus be supposed to have the power to ‘move those of other people as well’ (Euth. -

Ancient Greek Painting and Mosaics in Macedonia

ANCIENT GREEK PAINTING AND MOSAICS IN MACEDONIA All the manuals of Greek Art state that ancient Greek paintinG has been destroyed almost completely. Philological testimony, on the other hand, how ever rich, does no more than confirm the great loss. Vase painting affirms how skilful were the artisans in their drawings although it cannot replace the lost large paintinG compositions. Later wall-paintings of Roman towns such as Pompeii or Herculaneum testifying undoubted Greek or Hellenistic influ ence, enable us to have a glimpse of what the art of paintinG had achieved in Greece. Nevertheless, such paintings are chronologically too far removed from their probable Greek models for any accurate assessment to be made about the degree of dependence or the difference in quality they may have had between them. Archaeological investigation, undaunted, persists in revealing methodi cally more and more monuments that throw light into previously dark areas of the ancient world. Macedonia has always been a glorious name in later Greek history, illumined by the amazing brilliance of Alexander the Great. Yet knowledge was scarce about life in Macedonian towns where had reigned the ancestors and the descendants of that unique king, and so was life in many other Greek towns situated on the shores of the northern Aegean Sea. It is not many years ago, since systematic investigation began in these areas and we are still at the initial stage; but results are already very important, es pecially as they give the hope that we shall soon be able to reveal unknown folds of the Greek world in a district which has always been prominent in the his torical process of Hellenism. -

Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures

www.idosr.org Ahmed ©IDOSR PUBLICATIONS International Digital Organization for Scientific Research ISSN: 2579-0765 IDOSR JOURNAL OF CURRENT ISSUES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES 6(1): 45-49, 2020. Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures Ahmed Wahid Yusuf Department of Museum Studies, Menoufia University, Egypt. ABSTRACT The Greeks made major contributions to math and science. We owe our basic ideas about geometry and the concept of mathematical proofs to ancient Greek mathematicians such as Pythagoras, Euclid, and Archimedes. Some of the first astronomical models were developed by Ancient Greeks trying to describe planetary movement, the Earth’s axis, and the heliocentric system a model that places the Sun at the center of the solar system. The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. The research further shows the influence science has in the ancient Greek sculptures. Keywords: Greek, Sculpture, Astronomers, Pottery. INTRODUCTION The sculpture of ancient Greece is the of the key points of Ancient Greek main surviving type of fine ancient Greek philosophy was the role of reason and art as, with the exception of painted inquiry. It emphasized logic and ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient championed the idea of impartial, rational Greek painting survives. Modern observation of the natural world. scholarship identifies three major stages The Greeks made major contributions to in monumental sculpture in bronze and math and science. We owe our basic ideas stone: the Archaic (from about 650 to 480 about geometry and the concept of BC), Classical (480-323) and Hellenistic mathematical proofs to ancient Greek [1]. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011)

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 27 | 2014 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) Angelos Chaniotis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2266 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2266 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 November 2014 Number of pages: 321-378 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) », Kernos [Online], 27 | 2014, Online since 01 October 2016, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/2266 This text was automatically generated on 15 September 2020. Kernos Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) 1 Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2011 (EBGR 2011) Angelos Chaniotis 1 The 24th issue of the Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion presents epigraphic publications of 2011 and additions to earlier issues (publications of 2006–2010). Publications that could not be considered here, for reasons of space, will be presented in EBGR 2012. They include two of the most important books of 2011: N. PAPAZARKADAS’ Sacred and Public Land in Ancient Athens, Oxford 2011 and H.S. VERSNEL’s Coping with the Gods: Wayward Readings in Greek Theology, Leiden 2011. 2 A series of new important corpora is included in this issue. Two new IG volumes present the inscriptions of Eastern Lokris (119) and the first part of the inscriptions of Kos (21); the latter corpus is of great significance for the study of Greek religion, as it contains a large number of cult regulations; among the new texts, we single out the ‘sacred law of the tribe of the Elpanoridai’ in Halasarna. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

Volume 16 Winter 2014

Volume 16 Winter 2014 Tomb 6423 At right, the Below is the A Digger’s View: lastra sealing chamber as The Tomb of the Hanging the chamber found at the The perspective of a field Aryballos, Tarquinia shown in situ. moment of archaeologist by Alessandro Mandolesi Above it is the opening, by Maria Rosa Lucidi another lastra on the back The University of Turin and the possibly reut- wall a little The discovery of the tomb of the Superintendency for the Archaeological ilzed spolia aryballos still “hanging aryballos" has aroused great Heritage of Southern Etruria have been interest among the public in both Italy taken from hangs on its investigating the Tumulus of the Queen and internationally. The integrity of the original nail. and the necropolis surrounding it, the the tumulus unviolated tomb is definitely one of the Doganaccia, since 2008. The excava- of the queen, (photographs reasons for the attention it has received. tions have brought forth many important which stands by Massimo The uniqueness is even more pro- and unexpected results, thanks to subse- nearby. Legni). nounced when one considers that since quent research, and the infor- the second half of the nine- mation relating to the differ- teenth century the English ent phases of its use has made traveler George Dennis it possible to clarify many blamed the inability to recov- obscure points about the great er the contexts from intact era of the monumental tumuli chamber tombs in Etruscan at Tarquinia. Tarquinia on repeated looting Archaeologists working since ancient times. The